THE IMPACTS of SMALL SCALE ARTISANAL DIAMOND MINING on the ENVIRONMENT By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ganspan Draft Archaeological Impact Assessment Report

CES: PROPOSED GANSPAN-PAN WETLAND RESERVE DEVELOPMENT ON ERF 357 OF VAALHARTS SETTLEMENT B IN THE PHOKWANE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY, FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Archaeological Impact Assessment Prepared for: CES Prepared by: Exigo Sustainability ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (AIA) ON ERF 357 OF VAALHARTS SETTLEMENT B FOR THE PROPOSED GANSPAN-PAN WETLAND RESERVE DEVELOPMENT, FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Conducted for: CES Compiled by: Nelius Kruger (BA, BA Hons. Archaeology Pret.) Reviewed by: Roberto Almanza (CES) DOCUMENT DISTRIBUTION LIST Name Institution Roberto Almanza CES DOCUMENT HISTORY Date Version Status 12 August 2019 1.0 Draft 26 August 2019 2.0 Final 3 CES: Ganspan-pan Wetland Reserve Development Archaeological Impact Assessment Report DECLARATION I, Nelius Le Roux Kruger, declare that – • I act as the independent specialist; • I am conducting any work and activity relating to the proposed Ganspan-Pan Wetland Reserve Development in an objective manner, even if this results in views and findings that are not favourable to the client; • I declare that there are no circumstances that may compromise my objectivity in performing such work; • I have the required expertise in conducting the specialist report and I will comply with legislation, including the relevant Heritage Legislation (National Heritage Resources Act no. 25 of 1999, Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983 as amended, Removal of Graves and Dead Bodies Ordinance no. 7 of 1925, Excavations Ordinance no. 12 of 1980), the -

Frances Baard District Municipality: Proposed Upgrading of an Anglo Boer War Blockhouse on a Portion of Warrenton Erf 1, Warrenton, Northern Cape Province

FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY: PROPOSED UPGRADING OF AN ANGLO BOER WAR BLOCKHOUSE ON A PORTION OF WARRENTON ERF 1, WARRENTON, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Archaeological Impact Assessment Prepared for: Frances Baard District Municipality Prepared by: Exigo Sustainability -i- Firefly Investments 224: Platinum Solar Park Project Archaeological Impact Assessment Report HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT ON A PORTION OF WARRENTON ERF 1 FOR THE PROPOSED UPGRADING OF AN ANGLO BOER WAR BLOCKHOUSE, WARRENTON, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Conducted on behalf of: Frances Baard District Municipality Exigo Sustainability Compiled by: Nelius Kruger (BA, BA Hons. Archaeology Pret.) Reviewed by: Joh-ne Jansen (Frances Baard District Municipality) Document History Document Version 1 (Draft) – 25 March 2016 -i- Firefly Investments 224: Platinum Solar Park Project Archaeological Impact Assessment Report Although Exigo Sustainability exercises due care and diligence in rendering services and preparing documents, Exigo Sustainability accepts no liability, and the client, by receiving this document, indemnifies Exigo Sustainability and its directors, managers, agents and employees against all actions, claims, demands, losses, liabilities, costs, damages and expenses arising from or in connection with services rendered, directly or indirectly by Exigo Sustainability and by the use of the information contained in this document. This document contains confidential and proprietary information equally shared between Exigo Sustainability. and Frances Baard District Municipality, and is protected by copyright in favour of these companies and may not be reproduced, or used without the written consent of these companies, which has been obtained beforehand. This document is prepared exclusively for Frances Baard District Municipality and is subject to all confidentiality, copyright and trade secrets, rules, intellectual property law and practices of South Africa. -

27 the Alluvial Diamond Deposits of The

TR ClI- 27 THE ALLUVIAL DIAMOND DEPOSITS OF THE LOWER VAAL RIVER BETWEEN BARKLY WEST AND THE VAAL-HARTS CONFLUENCE IN THE NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA By FABRICE GILBERT MATHEYS B.Sc. (Hons) Thesis snbmitted in partial fnlfllment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Geology . Rhodes University Grahamstown DECEMBER 1990 ABSTRACT The alluvial diamond deposits along the Vaal River, between Barkly West and the Vaal-Harts confluence, have been worked for more than one century by thousands of private diggers. The diamonds are recovered from two sedimentary units of Cenozoic age, the Older Gravels and the Younger Gravels. These rest on a basement of Ventersdorp Supergroup andesites and Karoo Sequence sediments, which have been intruded by Cretaceous kimberlites. The gravels are, in turn, overlain by the Riverton Formation and the Hutton Sand. On a large scale, tectonic setting, geomorphology and palaeoclimate have played a major role in the formation of diamondiferous placers in the araa under investigation. A study of the sedimentology of the Younger Gravels was carried out with the aim of acquiring an understanding of tha processes responsible for the economic concentration of high quality diamonds. An investigation of facies assemblages, clast composition, clast size, external geometry, particle morphology and palaeocurrent directions led to the conclusion that the Younger Gravels were deposited in a proximal braided stream environment during high discharge. A small-scale experiment was carried out to test the efficiency of different sedimentological trap sites in concentrating kimberlite indicator minerals. The results show that the concentration of indicator minerals is dependent o~the size fraction choosen, bed roughness and gravel calibre. -

Frances Baard District Municipality: Proposed Nkandla Extension 2 Township Establishment, Erf 258 Nkandla, Hartswater, Northern Cape Province

FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY: PROPOSED NKANDLA EXTENSION 2 TOWNSHIP ESTABLISHMENT, ERF 258 NKANDLA, HARTSWATER, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Archaeological Impact Assessment Prepared for: Frances Baard District Municipality Prepared by: Exigo Sustainability -i- Firefly Investments 224: Platinum Solar Park Project Archaeological Impact Assessment Report ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (AIA) OF AREAS DEMARACTED FOR THE PROPOSED NKANDLA EXTENSION 2 TOWNSHIP ESTABLISHMENT ON A PORTION OF ERF 258 NKANDLA, FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Conducted on behalf of: Frances Baard District Municipality Exigo Sustainability Compiled by: Nelius Kruger (BA, BA Hons. Archaeology Pret.) Reviewed by: Freddy Netshivhodza (Frances Baard District Municipality) Document History Document Version 1 (Draft) – 25 March 2016 Document Version 2 (Final) – 31 March 2016 -i- Firefly Investments 224: Platinum Solar Park Project Archaeological Impact Assessment Report Although Exigo Sustainability exercises due care and diligence in rendering services and preparing documents, Exigo Sustainability accepts no liability, and the client, by receiving this document, indemnifies Exigo Sustainability and its directors, managers, agents and employees against all actions, claims, demands, losses, liabilities, costs, damages and expenses arising from or in connection with services rendered, directly or indirectly by Exigo Sustainability and by the use of the information contained in this document. This document contains confidential and proprietary information equally shared between Exigo Sustainability. and Frances Baard District Municipality, and is protected by copyright in favour of these companies and may not be reproduced, or used without the written consent of these companies, which has been obtained beforehand. This document is prepared exclusively for Frances Baard District Municipality and is subject to all confidentiality, copyright and trade secrets, rules, intellectual property law and practices of South Africa. -

Integrated Waste Management Plan

FBDM IWMP FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY NTEGRATED ASTE ANAGEMENT LAN I W M P INTEGRATED WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN (Final) October 2010 ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL CONSULTANTS P.O. BOX 1673 147 Bram Fischer Drive Tel: 011 781 1730 SUNNINGHILL FERNDALE Fax: 011 781 1731 2157 2194 Email: [email protected] Copyright Nemai Consulting 2010 STATUS QUO - DRAFT i FBDM INTEGRATED WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN TITLE AND APPROVAL PAGE TITLE: Frances Baard District Municipality Integrated Waste Management Plan: Status Quo Report (Draft) CLIENT: Frances Baard District Municipality Private Bag X6088 Kimberley 8300 PREPARED BY: Nemai Consulting C.C. P.O. Box 1673 Sunninghill 2157 Telephone : (011) 781 1730 Facsimile : (011) 781 1731 AUTHORS: Elani Holton, Ciaran Chidley, Val-Mari van Schalkwyk __________________________ __________________ Signature Date APPROVAL __________________________ __________________ Signature Date FBDM IWMP – September 2010 i FBDM INTEGRATED WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN AMENDMENTS PAGE Date Nature of Amendment Amendment No. Signature First Draft of Status Quo for 09 June 2010 0 Client Review Draft of IWMP for Client 30 July 2010 1 Review Draft IWMP for Public 30 August 2010 2 Review 30 September 2010 Final IWMP 3 FBDM IWMP – September 2010 ii FBDM INTEGRATED WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE AND APPROVAL PAGE i AMENDMENTS PAGE ii TABLE OF CONTENTS iii LIST OF FIGURES vi LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF PLATES ix LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS x GLOSSARY OF TERMS xii 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Study Aims 1 1.2 Methodology 2 1.3 Structure of the Document 3 1.4 Compliance with the Requirements of the Waste Act 5 1.5 Alignment with the Northern Cape Provincial IWMP 7 2. -

Report Format NI 43-101

2010 Tania R Marshall Explorations Unlimited Glenn A Norton Rockwell Diamonds Inc REVISED TECHNICAL REPORT ON THE WOUTERSPAN ALLUVIAL DIAMOND PROJECT, HERBERT DISTRICT, SOUTH AFRICA FOR ROCKWELL DIAMONDS INC Effective Date: 30 November, 2010 Signature Date: 30 May2011 Revision Date 25 July 2011 ROCKWELL DIAMONDS INC, WOUTERSPAN PROJECT November 30, 2010 Table of Contents Page 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 13 1.1 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND SCOPE OF WORK ....................................................................................................... 13 1.2 SOURCES OF INFORMATION .............................................................................................................................. 15 1.3 UNITS AND CURRENCY .................................................................................................................................... 16 1.4 FIELD INVOLVEMENT OF QUALIFIED PERSON ........................................................................................................ 16 1.5 USE OF DATA ................................................................................................................................................ 16 2 RELIANCE ON OTHER EXPERTS ..................................................................................................................... 18 2.1 LEGAL OPINION ............................................................................................................................................ -

Dictionary of South African Place Names

DICTIONARY OF SOUTHERN AFRICAN PLACE NAMES P E Raper Head, Onomastic Research Centre, HSRC CONTENTS Preface Abbreviations ix Introduction 1. Standardization of place names 1.1 Background 1.2 International standardization 1.3 National standardization 1.3.1 The National Place Names Committee 1.3.2 Principles and guidelines 1.3.2.1 General suggestions 1.3.2.2 Spelling and form A Afrikaans place names B Dutch place names C English place names D Dual forms E Khoekhoen place names F Place names from African languages 2. Structure of place names 3. Meanings of place names 3.1 Conceptual, descriptive or lexical meaning 3.2 Grammatical meaning 3.3 Connotative or pragmatic meaning 4. Reference of place names 5. Syntax of place names Dictionary Place Names Bibliography PREFACE Onomastics, or the study of names, has of late been enjoying a greater measure of attention all over the world. Nearly fifty years ago the International Committee of Onomastic Sciences (ICOS) came into being. This body has held fifteen triennial international congresses to date, the most recent being in Leipzig in 1984. With its headquarters in Louvain, Belgium, it publishes a bibliographical and information periodical, Onoma, an indispensable aid to researchers. Since 1967 the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) has provided for co-ordination and liaison between countries to further the standardization of geographical names. To date eleven working sessions and four international conferences have been held. In most countries of the world there are institutes and centres for onomastic research, official bodies for the national standardization of place names, and names societies. -

David Roger Neacalbann Mcintyre Morris

CURRICULUM VITAE: DAVID ROGER NEACALBANN MCINTYRE MORRIS McGregor Museum, P.O. Box 316, Kimberley & Dept Anthropology & Sociology, University of the Western Cape David Morris is Head of Archaeology at the McGregor Museum in Kimberley, and has a PhD from the University of the Western Cape in Cape Town. His doctoral research revolved on the rock art of the Northern Cape, his prior Masters dissertation having focused on the site of Driekopseiland near Kimberley. He has done extensive fieldwork in the Karoo, while recent work has included research at sites north of the Orange River and in the vicinity of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park. His museum research addresses a wide cross-section of Northern Cape archaeological and historical matters. His interests include public archaeology, and he was closely involved in developing the Wildebeest Kuil Rock Art Centre outside Kimberley and in writing the SAHRA-approved Conservation Management Plan for Wonderwerk Cave near Kuruman. With John Parkington and photographer Neil Rusch, he has co-authored the book Karoo rock engravings (2008). He is currently preparing a monograph on Wildebeest Kuil as part of a Franco-South African Groupe de Recherche International partnership and research programme, and has helped co-edit chapters for a forthcoming book, Working with rock art: international perspectives, the proceedings of an international SACRA conference held in Kimberley in 2006. He has attended rock art meetings in France and Mexico and is a partner in the South Africa- Mexico rock art programme launched in 2008 and broadened to include Botswana and Moçambique (2009). He addressed colleagues in archaeology at the Russian Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg in 2004. -

FIN MAIN TABLE PR MP CODE MP NAME MN PR C 10101 Doringbaai 101 10102 Ebenhaesar 101 10103 Klawer 101 10104 Koekenaap 101 10105 L

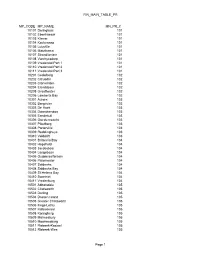

FIN_MAIN_TABLE_PR MP_CODE MP_NAME MN_PR_C 10101 Doringbaai 101 10102 Ebenhaesar 101 10103 Klawer 101 10104 Koekenaap 101 10105 Lutzville 101 10106 Matzikama 101 10107 Strandfontein 101 10108 Vanrhynsdorp 101 10109 Vredendal Part 1 101 10110 Vredendal Part 2 101 10111 Vredendal Part 3 101 10201 Cederberg 102 10202 Citrusdal 102 10203 Clanwilliam 102 10204 Elandsbaai 102 10205 Graaffwater 102 10206 Lamberts Bay 102 10301 Aurora 103 10302 Bergrivier 103 10303 De Hoek 103 10304 Dwarskersbos 103 10305 Eendekuil 103 10306 Goedverwacht 103 10307 Piketberg 103 10308 Porterville 103 10309 Redelinghuys 103 10310 Velddrift 103 10401 Britannia Bay 104 10402 Hopefield 104 10403 Jacobsbaai 104 10404 Langebaan 104 10405 Oudekraalfontein 104 10406 Paternoster 104 10407 Saldanha 104 10408 Saldanha Bay 104 10409 St Helena Bay 104 10410 Swartriet 104 10411 Vredenburg 104 10501 Abbotsdale 105 10502 Chatsworth 105 10503 Darling 105 10504 Dassen Island 105 10505 Greater Chatsworth 105 10506 Ilinge Lethu 105 10507 Kalbaskraal 105 10508 Koringberg 105 10509 Malmesbury 105 10510 Moorreesburg 105 10511 Riebeek-Kasteel 105 10512 Riebeek-Wes 105 Page 1 FIN_MAIN_TABLE_PR 10513 Swartland 105 10514 The Grotto Bay 105 10515 Yzerfontein 105 10601 Bella Vista 106 10602 Ceres 106 10603 eNduli 106 10604 Meulstroom 106 10605 Op-die-Berg 106 10606 Paerde Kraal Bosreservaat 106 10607 Prince Alfred Hamlet 106 10608 Steinthal 106 10609 Tulbagh 106 10610 Witzenberg 106 10611 Wolseley 106 10701 Dal Josafat Forest Reserve 107 10702 Drakenstein 107 10703 Drommedaris 107 10704 Gouda -

Waterresearch Commission

WATERRESEARCH COMMISSION LONG TERM SALT BALANCE OF THE VAALHARTS IRRIGATION SCHEME C E Herold and A K Bailey REPORT TO THE WATERRESEARCH COMMISSION by STEWART SCOTT INCORPORATED (Consulting Engineers) P O Box 784506, Sandton, 2146 12/07/1996 WRC Report No.: 420/1/96 ISBN No.: 1 86845 0414 (i) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BACKGROUND AND MOTIVATION Vaalharts is the largest irrigation scheme in the Republic of South Africa. The Vaal River is the source of the water supply to the scheme. Since the commissioning of Vaalharts in the mid-thirties, the salinity of the supply water has deteriorated substantially due to large scale urban, industrial and mining developments in the Middle Vaal. A study of the Harts River carried out by Stewart Sviridov and Oliver in 1987 on behalf of the Department of Water Affairs (DWA) concluded that between 1935 and 1984 less than 20 percent of the salt contained in the water supplied to Vaalharts was released via return flows to the Harts River. This represents an overall accumulation of approximately 3 million tons of salt. Implications for the Vaal and Orange River systems Salinisation of the Vaal River has already led to serious water quality problems in the lower Vaal. The return of all of the salt contained in the irrigation water supplied to Vaalharts would have put an additional 100 000 tons of salt into the Lower Vaal each year, with serious economic consequences for downstream users. If this proves to be only a temporary phenomenon (i.e. lagged system response) then continued salinisation of the Middle Vaal could jeopardise all irrigation schemes downstream of the Vaal-Harts confluence. -

Water Related Impacts of Small Scale Mining

WATER RELATED IMPACTS OF SMALL SCALE MINING Final Report to the Water Research Commission by R Heath, M Moffett and S Banister Pulles Howard & de Lange Incorporated WRC Report No 1150/1/04 ISBN No 1-77005-119-8 MARCH 2004 Disclaimer This report emanates from a project financed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and is approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC or the members of the project steering committee, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background Small-scale mining already occurs on a sizeable scale in South Africa, and active measures are being taken by government to promote the development of this sector of the economy. It is realised that the success of this sector depends largely on providing these miners with technical assistance. The Department of Minerals and Energy (DME) has initiated the development of a National Small-Scale Mining Development Framework. This framework will ultimately be available to provide assistance to small-scale miners regarding the necessary regulatory and administrative procedures, reserve determination, business plans and mining methods. Aims The aims of the study were to identify and characterize the critical aspects with regard to the water-related impacts of small-scale mining. Once these impacts were identified, the aim was to develop and recommend appropriate strategies to assist small-scale miners in environmental management. Approach Followed The methodology that was followed in the course of this project included the following: A literature review was undertaken. -

In This Issue

Metsi Ke Bophelo Issue 1 - March/April 2011 In this issue 2 Editorial note 9 Sedibeng Water capacitates municipalities 3 Upcoming events 10 Employees introduced toAARTOAct 3 Long service awards 11 Sedibeng Water receives accolades 4-5 Aworld first for Sedibeng Water 12 Incident investigation training 6 Sedibeng Water sponsors river clean-up campaign 12 New vehicles for the North West Region 6 Sedibeng Water adopts Mothibistad Park 13 MDP students graduate 7 Vandalism 14 Mmamokua retires after 28 years 8 Training course for secretaries and personal assistants presented 15-16 Staff profiles Editorial note Steering through the storm The editorial team welcomes you to 2011, as well as to our term viability and sustainability. Financial stability and first issue of Metsi Ke Bophelo for the year – we are proud to sustainability is not Sedibeng Water's only measure of be part of this organisation and look forward to a productive success. year of achievements for all. Our financial results make it possible to grow and maintain During 2010 Sedibeng Water made its mark in many our operations, while also caring for the environment respects. An independent customer survey indicated that before giving clean water supply and hygienic living we maintained customer satisfaction levels of 80,4% and conditions to even the poorest of the poor! 78,3% amongst our retail and bulk customers respectively. We are also assisting in the implementation of the Blue In addition, Sedibeng Water has once again been Drop programme - we offer training to municipal staff acknowledged when we recently received the Diamond responsible for Blue Drop functions.