The Impact of the Straw Plait and Hat Trade in Nineteenth-Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FORWARD PLAN Notice Of

HERTFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL FORWARD PLAN Notice of (a) key and other decisions likely to be made on behalf of the County Council by Cabinet, (b) key decisions likely to be made on behalf of the County Council by Officers and (c) decisions on Traffic Regulation Orders likely to be made by Officers on behalf of the County Council in the period 1 September 2019 – 31 December 2019 Published: 7th August 2019 [Note: Key decisions and other decisions due to be reached in August 2019 but not yet made remain listed (notice of these items was given in the Forward Plan issued on 4 July 2019)] Contents DECISIONS BY CABINET KEY DECISIONS BY CHIEF OFFICERS Subject Subject New items are shown in bold. Ref. No. Matter for Decision Ref. No. Matter for Decision A032/19 Next Generation Programme: Approval of the service delivery options B001/19 Traffic Regulation Orders - various (see attached Schedule Appendix 1) for decision presented as part of the Outline Business Case A043/19 To agree the recommendations as set out in the Broxbourne Air B104/17 New contract for the Provision of a Two bed Emergency Therapeutic Quality Project Outline and Final Business Case Study residential Unit for Children and Young People aged 11-16 with Challenging and Complex Needs (Hudnall Park) A044/19 Approval of Winter Service Operational Plan 2019/20 B102/18 Procurement for the provision of an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) System for Herts FullStop: Award of contract A046/19 Extension of existing credit facility available to Herts Living Ltd B109/18 HCC1810703 – Property -

Viability Assessment Stage 1

ASSESSING VIABILITY Community Infrastructure Levy: A Stage 1 Economic Viability Assessment prepared for 8 Hertfordshire Authorities: Dacorum Borough Council Three Rivers District Council Watford Borough Council Hertsmere Borough Council Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council St Albans City and District Council East Herts Council Borough of Broxbourne AUTHORITY SPECIFIC VERSION FOR THREE RIVERS DISTRICT COUNCIL Report by: Lambert Smith Hampton: December 2012 Final Assessing Viability Community Infrastructure Levy: A Stage 1 Economic Viability Study: Authority Specific Version for Three Rivers District Council Prepared for: 8 Hertfordshire Authorities Prepared by Lambert Smith Hampton UK House, 180 Oxford Street London W1D 1NN Tel: 020 7198 2000 Fax: 020 7198 2001 Date: December 2012 Foreword: about the authority specific version of this report The Stage 1 Economic Viability Study was commissioned as a single entity and subsequently prepared and delivered by Lambert Smith Hampton as a single report containing the complete data for all 8 client authorities: its contents were discussed and agreed with them in this form. The advantage of this was that it has enabled a composite picture of CIL viability issues to be presented to the clients and discussed collectively with them before finalisation, and there have been many benefits for them in considering these matters as a totality rather than viewing them in isolation. Each district indicated during the course of the report's preparation that they would want to publish a version that focused on data pertaining to that district, and isolated extraneous data relevant only to other authorities. This is that version: it is the authority specific report for Three Rivers District Council. -

Descendant Indent Chart

Descendant Indented Chart of George Burchmore of Row End Farm George1 BURCHMORE (723), b. 16 Dec 1762 at Flamstead, Hemel Hempstead, HRT, England, d. 1 Aug 1843 at Flamstead, Hemel Hempstead, HRT, England, bur. after 1 Aug 1843 at Flamstead, Hemel Hempstead, HRT, England +Susannah1 REDDING (727), b. 1763 at Redbourn, HRT, England, m. 29 Oct 1784 at Flamstead, Hemel Hempstead, HRT, England, d. 13 Jan 1788 at Row End, Flamstead, HRT, England ├── George2 BURCHMORE (277), b. before 20 Jan 1786 at Flamstead, Hemel Hempstead, HRT, England, d. 2 Dec 1838 at Flamstead, Hemel │ Hempstead, HRT, England, bur. after 31 Jan 1838 at Flamstead, Hemel Hempstead, HRT, England │ +Elizabeth2 PLUMMER (5552), b. 1790 at Studham, BDF, England, com. circa 1813 │ └── George (Studham)3 BIRCHMORE PLUMMER (5553), b. 10 Jul 1813 at Studham, BDF, England, d. 13 Mar 1884 at Whipsnade, │ Dunstable, BDF, England │ +Ann3 MATTHEWS (8668), b. 1815 at Whipsnade, Dunstable, BDF, England, m. 1 Oct 1835 at Whipsnade, Dunstable, BDF, │ England, d. 1858 at Whipsnade, Dunstable, BDF, England │ ├── George4 BIRCHMORE (PLUMMER) (8150), b. 1850 at Whipsnade, Dunstable, BDF, England, d. Jun 1915, bur. 24 Jun │ │ 1915 at Lambeth, London, SRY, England │ └── Lucy4 BIRCHMORE (19956), b. 1857 │ +Ruth3 COOK (6884), b. 1819 at Kensworth, Dunstable, HRT, England, d. 22 May 1904 at Whipsnade, BDF, England │ └── Ruth4 BIRCHMORE (9248), b. 1857 │ +Eliza3 BATCHELOR (5561), b. 1829 at Whipsnade, Dunstable, BDF, England, m. 18 Jun 1859 at London, MDX, England, d. 19 Aug │ 1867 at Whipsnade, Dunstable, BDF, England │ ├── Ellen4 BIRCHMORE (5562), b. 21 Mar 1860 at Whipsnade, Dunstable, BDF, England, d. -

OFFICE to LET from 1,847 Sq Ft (171.65 Sq M)

Unit 6A, Quickbury Farm, Hatfield Heath Road, Sawbridgeworth Herts CM21 9HY OFFICE TO LET From 1,847 sq ft (171.65 sq m) • Fully refurbished office space • Good parking provision • Available immediately • Attractive rural setting but close to Sawbridgeworth station www.cokegearing.co.uk Unit 6A, Quickbury Farm, Hatfield Heath Road, Sawbridgeworth, Herts CM21 9HY Location: Business Rates: The property is located in an attractive rural setting, half a mile from The offices are currently unrated. Sawbridgeworth station. Sawbridgeworth is a Hertfordshire market town with rail connections to London Liverpool Street. EPC: The EPC rating is C - 73 Bishop’s Stortford, with a population of circa 40,000, is situated approximately 4 miles to the north and Harlow approximately 3 miles to the south, both with Costs: connections to the M11 and wider motorway infrastructure. Stansted Airport Each party to pay their own costs in this matter. is is circa 6 miles away. Description A single-storey converted barn property which has been fully refurbished to provide mainly open plan office space. The main area, which provides open plan space for approximately 20 staff, leads through to a meeting room area and thereafter a kitchen/breakout facility and WCs. To the side of the property is a separate room providing a large boardroom area together with further storage. We understand there is a standard fibre internet connection on the site (not confirmed or tested) and the space is fully air-conditioned with LED lighting. The property is situated within Quickbury Farm, which has a number of further office occupiers. Externally there are approximately six parking spaces outside the property and overflow parking in the adjacent car park. -

Hertfordshire. Cop 231

COURT DffiECrORY.] HERTFORDSHIRE. COP 231 Clark T. West View rd.Heml.Hempstd C{)cks Benjamin, Buntingford RS.O Conisbee Wilfd, Victoriard.Nw.Barnet Clark W. Henry, Piggob fa1"Ill, Little Cockman Miss, 1 Wellington villas, Conisbee Joseph, Lilley cottage, :East Albury, Hadham S.O Broxbourne S.O Barnet road, New Barnet Clark Walter Frederick, Cheshunt st. Cockrem Rev. Oliver Carter ¥.A., Connolly Michael, St. Edmund's col- Waltham Cross LL.D. Watford lege, Standon, Ware Clarke Rev. C. W., M.A. Wallington, Cocks John Robert, 32 Fore street, Connop Herbert M.A. Boreham house, Baldock Hertford Elstree RS.O Clarke Rev.W. Th.A.K.o.L.Ridge,Brnt Cocks RDbert, 12 West st. Hertford Conquest Mrs. Windhill road, Bishop's Clarke Rev. Wm. W. Essendon, Hatfid Cocks Wm. Douro ho. Standon, Ware Stortford Clarke Arthur Mayhew, Northfield, Cockshut Harry, Fernbank, Church- Constable Alfred, 261 High st. Watford Sawbridgeworth RS.O gate, Cheshunt, Waltham Cross Consterdine Rev. Jas. M.A. !Parsonage, Clarke Yooth Frederick, Much Wy- Coe Miss, Iona, Market street, Watford Little Heath, Potter'!! Bar S.O mondley, Stevenage Coe Mrs. 74 Wood street, High Barnet Conway William Thomas, North lodge, Clarke Charles William, Lucerne villa, Coffin Rd. E. 3 Lothair villas, Hatfield Somerset road, New Barnet Wiggenhall road, Watford Coggin: Rev. Frank. Ernes1i M.A. Vi- Cook Alfred M. Red house, Herting- Clarke Edwd. St. Stephens, St.Albans carage, Lemsford, Hatfield fordbury, Hertford Clarke E. Chalk hill, Bushey, Watford Cohen Joseph, Cravenhurst, Market Cook R The Poplars, Stevenage, Herts Clarke Frederick WilIiam, Hazeldean, street, Watford Cook Charles, New road, Ware Lemsford road, St. -

The Friday Email

THE FRIDAY EMAIL Friday 15th January 2021 The Friday Thought from our Associate Priest, Revd Debbie Our lives are full of endless chatter, be that from the TV, radio, our phones, social media, you name it. As a result of the current crisis, I expect that you, like me, are watching more news items and government briefings than ever before. It seems we’re either being bombarded with noise or actively seeking it out; some would say like an addiction, which drowns out our own thoughts and opportunities for meaningful reflection. I do wonder at times, how much of the babble I really hear? The reading from Samuel underscores the importance of listening. While Samuel is sleeping, he believes he hears someone calling his name. So Samuel wakes up and runs to Eli thinking Eli has called. "Here I am, Lord," he says, running to old Eli who stumbles out of bed and grumbles, "Go back to sleep, you're hearing things." After responding to hearing his name called several times, Eli instructs Samuel to "Go to sleep, and if you are called reply: 'Speak, Lord, for your servant is listening.'" So Samuel follows Eli's orders, and when called upon again, he responds accordingly. And so Samuel grows up with the Lord accompanying him, giving him insight, wisdom, and strength as one of his prophets. This was a time in Israel’s history when Israel was out of communication with God. Eli was getting too old to lead (his loss of vision is what happens to the elderly but is also symbolic of the people’s inability to see the things of God), and his sons were wicked. -

A Miller's Tale – the Life Of

A MILLER’S TALE – THE LIFE OF THOMAS BURTON (1859 – 1938) Thomas Burton was a true scion of Sawbridgeworth. His grandfather John was born here in 1800, and in the 1841 census was living in Cock Street (now Bell Street) in the centre of the town, with his wife Sophia (née Waller) and family. Thomas’ father had the same name, being called Thomas Waller Burton. This Thomas was born in Sawbridgeworth in 1827. In the 1841 census he is shown as serving with the Royal Navy, but by 1851 has returned to Sawbridgeworth and is also living in Cock Street. He was married to Fanny Groves in 1857 and was a builder. Thomas was born in Cock Street on 5 April 1859. He was the second eldest of five children, having two brothers and two sisters. His very early life is obscure. Presumably he intended to follow his father into the building trade, but on 30 September 1885, Thomas married Clara Littler. This is important, because, although her father was a butcher, she was also a member of a long-established family of millers. As long ago as the early 1700s (between 1720 and 1737), an Andrew and Nathaniel Littler are recorded as the millers at both Sawbridgeworth Mill and Sheering Mill. Furthermore, in 1911 a Fanny Littler of Lower Sheering, is recorded as a mortgagee in respect of Sawbridgeworth Mill. Presumably, Thomas’ marriage to Clara made him think seriously about becoming a miller. Accordingly, in 1891, probably (given the 1911 Stort Deeds document) with financial help from the Littler family, he purchased Sawbridgeworth Mill from the local politician Edmund Broughton Barnard. -

Sawbridgeworth to Bishop's Stortford

Sawbridgeworth to Bishop’s Stortford (Full Walk) Sawbridgeworth to Bishop’s Stortford (Short Walk) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 15th March 2014 06th July 2019 06th July 2019 Current status Document last updated Sunday, 07th July 2019 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2014-2019, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Sawbridgeworth to Bishop’s Stortford (via Henry Moore Foundation) Start: Sawbridgeworth Station Finish: Bishop’s Stortford station Sawbridgeworth Station, map reference TL 490 150, is 6 km south of Bishop’s Stortford, and 48m above sea level. Bishop’s Stortford Station, map reference TL 491 208, is 43 km northeast of Charing X and 61m above sea level. -

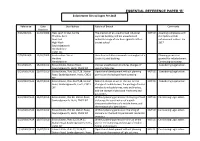

ESSENTIAL REFERENCE PAPER ‘B’ Enforcement Files Still Open Pre 2015

ESSENTIAL REFERENCE PAPER ‘B’ Enforcement files still open Pre 2015 Reference Date Site Address Nature of Breach Comments Received E/08/0021/A 11/01/2008 Hecc sport Cricket Centre The erection of an unauthorised industrial NOTICE Awaiting compliance with Tharbies Farm style link building and the unauthorised the OpDev and LB Rook End material change of use from agricultural to a enforcement notices. Jan High Wych cricket school 2017 Sawbridgeworth Hertfordshire CM21 0LL E/09/0018/B 15/01/2009 A site in Fore Street Unauthorised alteration works and neglect of a Planning permission Hertford Grade II Listed Building granted for refurbishment. Hertfordshire Continuing to monitor. E/10/0010/A 15/01/2010 Esbies Estate, Station Road, Various unauthorised structures changes of Considering Legal action. Sawbridgeworth, Herts, CM21 9JY use of untidy sites E/10/0010/A10 13/07/2010 Esbies Estate, Plots 26,27,28, Station Operational development without planning NOTICE Considering Legal action. Road, Sawbridgeworth, Herts, CM21 permission the laying of hard surfacing 9JY E/10/0010/A11 13/07/2010 Esbies Estate, Plots 26,27,28, Station Material change of use of the site for the NOTICE Considering Legal action. Road, Sawbridgeworth, Herts, CM21 storage of mobile homes, the parking of motor 9JY vehicles to inlcude lorries, vans and trailers, and the storage of plant and machinery and gas bottles. E/10/0010/A12 13/07/2010 Esbies Estate, Plot 29, Station Road, Without planning permission the laying of hard NOTICE Considering Legal action. Sawbridgeworth, Herts, CM21 9JY srufacing; the construction of a porch structure to the front of a mobile home; and the erection of a light column E/10/0010/A13 13/07/2010 Esbies Estate, Plot 29, Station Road, Without planning permission the siting of NOTICE Considering Legal action. -

The Upper Ver Valley Walk

VER VALLEY WALK 2 Teas, buns, pints and pies: Flamstead: The Three Blackbirds and The Spotted Dog Public Houses, plus Post Office store. The Upper Ver Valley Markyate: The Plume of Feathers Public House. Trowley Bottom: The Rose and Crown Public House. Explore the beautiful rolling countryside How to get there: of this river valley By road: Flamstead is approx 5 miles south of Dunstable, off the A5/ Watling Street. Leave Junction 9 of the M1 and follow the A5 north. Flamstead can be reached by any of the first turnings off to the left. There is a public car park in Friendless Lane, leading off Hollybush Lane. By public transport: Flamstead is served regularly by buses from St Albans and Dunstable. For details contact Intalink Traveline on 0871 200 2233 or visit www.intalink.org.uk Parts of this walk can be muddy or wet underfoot. This is one of a series of 8 circular walks on the River Ver and part of the 17 mile long linear, River Ver Trail. You can also use the OS Explorer Map 182 to find your way around the Valley. For lots more photos, memories, information and copies of the other walks go to www.riverver.co.uk The Countryside Management Service works with communities in Hertfordshire to help them care for and enjoy the environment. For information on further opportunities to enjoy Hertfordshire countryside, including Health Walks, visit www.hertslink.org/cms If you would like this leaflet produced in large print, please contact the Countryside Management Service on southwest. [email protected] Tel: 01462 459395 Front cover photo: St Leonard’s Church in the distance. -

OPEN CHURCH SUNDAY a to Z of CHURCHES OPEN in HERTFORDSHIRE

Across Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire OPEN CHURCH SUNDAY Sunday 21 June 2015 A to Z of CHURCHES OPEN IN HERTFORDSHIRE LOCATION, TIMINGS and ATTRACTIONS plus names of all churches open in Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire listed by Postcode ‘Seek and you will find……’ (Matthew 7.7) A to Z of Churches Open in Hertfordshire ANSTEY St George SG9 0TJ Open all day Features: 398th Bomb Group stained glass window. Graffiti. Lych Gate lock up. ARDELEY St Lawrence The Green SG2 7AQ Open from 8.45am to 6.45pm . Services at 9.30am and 6.00pm Features: Rood and rood loft. Carved roof angels. High Altar reredos. History booklet ARKLEY St Peter Barnet Road EN5 3JF Open from 11.00am to 4pm Teas Features: Stained glass windows. 175th anniversary of the Church. Beautiful Lady Chapel. Flower Festival ASPENDEN St Mary SG9 9PG Open from 11.00am to 4.00pm Tea, coffee, biscuits Features: Fine 19th century stained glass. Brasses. Rural setting. ASTON St Mary Broadwater Lane SG2 7EN Open from 10.00am to 5.00pm Light refreshments available Features: The Tower. Stained glass windows. Churchyard. Possible local history exhibition AYOT ST LAWRENCE St Lawrence Bibbs Hall Lane AL6 9BZ Open throughout the day Visit www.ayotstlawrence.com for details of events BARLEY St Margaret of Antioch Church End SG8 8JS Open all day Saturday 20th June: Church Fete at the Manor, 12noon to 4.00pm BAYFORD St Mary Church Lane SG13 8PP Open all day Features: Church listed. Wall and haha round churchyard. Victorian font cover. BENINGTON St Peter Church Green SG2 7LH Open all day BOREHAMWOOD Holy Cross Balmoral Drive WD6 2QU Open from 9.00am to 11.30pm and 2pm onwards Refreshments from 10.30am and 2pm onwards BOURNE END St John the Evangelist London Road HP1 2RU Open from 12noon to 4.00pm Tea, coffee, biscuits Features: Gilbert Scott design, built 1853, with Alfred Bell windows. -

Anita Bowman Roger Carter Hatfield Natalie Chalcraft Sawbridgeworth

The following players have been selected to play for the Presidents' Team vs North Mymms. Please check in by 2pm on the day. Please advise the Match officer, Peter McNulty as soon as possible of the following: ([email protected] Tel: 07710 218400) Your acceptance or non-availability to play Your telephone number Your dietary requirement if any Any extra meals if required and dietary if any If you are unable to stay for the after match meal you should state this in your reply and remind Peter on arrival. Anita Bowman Roger Carter Hatfield Natalie Chalcraft Sawbridgeworth Robin Chalcraft Sawbridgeworth Phil Clewes-Garner Sawbridgeworth Martin Duke De Havilland Marcia Dunstone Berkhamsted Mike Farrow Bishops Stortford Phil Havord Hatfield Kay Havord Hatfield John Loudon Hatfield Graham Marriner Potters Bar Sue Moodey Potters Bar Cathy Newman Bushey Mike Poole Welwyn & Dist Pam Rodgers Potters Bar Graham Searle Met Police Stuart Stamp Met Police Pat Stamp Met Police John Thompson Whit Hern Diane Thompson Hatfield Mich Van Put Hatfield Robin Williams Sawbridgeworth Dave Worker Holwell Reserves Joyce Terry Judi Simmons Charlie Bowie Herts Terry Barker Potters Bar Please note the dress code: In accordance with Dress Code Rules A & B Men’s regulation dress for attending County matches shall be: grey tailored trousers, dark blue blazer unless player has a National blazer, white shirt and County tie. For President’s matches players who do not have a County or National blazer may wear their club blazer / jacket. For match play in all matches shall be white tailored trousers or Bowls England regulation shorts, County shirt with either County or white jacket (if worn), shoes of an approved pattern and if worn socks, belts and braces to be white.