San Diego National Wildlife Refuge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Resources of the Southern Otay Mountain and Western Otay Mountain Wilderness Study Areas, San Diego County, California

Mineral Resources of the Southern Otay Mountain and Western Otay Mountain Wilderness Study Areas, San Diego County, California U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1711-E AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the cur rent-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Sur vey publications released prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that are listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" are no longer available. Prices of reports released to the open files are given in the listing "U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports," updated month ly, which is for sale in microfiche from the U.S. Geological Survey, Books and Open-File Reports Section, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices given below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications of general -

Maintaining a Landscape Linkage for Peninsular Bighorn Sheep

Maintaining a Landscape Linkage for Peninsular Bighorn Sheep Prepared by and Prepared for The Nature Conservancy April 2010 Maintaining a Landscape Linkage for Peninsular Bighorn Sheep Table of Contents Page Executive Summary iii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Study Area 2 1.3 Parque-to-Palomar—a Project of Las Californias Binational Conservation Initiative 4 2. Findings 5 2.1 Reported Occurrences 5 2.2 Habitat Model 6 2.3 Questionnaires and Interviews 7 2.4 Field Reconnaissance 10 3. Threats and Conservation Challenges 12 3.1 Domestic Livestock 12 3.2 Unregulated Hunting 12 3.4 Emerging Threats 13 4. Conclusions and Recommendations 15 4.1 Conclusions from This Study 15 4.2 Recommendations for Future Studies 16 4.3 Goals and Strategies for Linkage Conservation 17 5. Literature Cited 18 Appendices A. Questionnaire about Bighorn Sheep in the Sierra Juárez B. Preliminary Field Reconnaissance, July 2009 List of Figures 1. Parque-to-Palomar Binational Linkage. 3 2. A preliminary habitat model for bighorn sheep in northern Baja California. 8 3. Locations of reported bighorn sheep observations in the border region and the Sierra Juárez. 9 4. Potential access points for future field surveys. 11 CBI & Terra Peninsular ii April 2010 Maintaining a Landscape Linkage for Peninsular Bighorn Sheep Executive Summary The Peninsular Ranges extend 1,500 km (900 mi) from Southern California to the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula, forming a granitic spine near the western edge of the North American continent. They comprise an intact and rugged wilderness area connecting two countries and some of the richest montane and desert ecosystems in the world that support wide- ranging, iconic species, including mountain lion, California condor, and bighorn sheep. -

Border Agency Fire Council

BORDER AGENCY FIRE COUNCIL Year End Report 2011 & 2012 Border Agency Fire Council History The Border Agency Fire Council (BAFC) is made up of thirty-one United States and Mexican government agencies and organizations representing fire protection, law enforcement, legislators, emergency responders, natural resource managers, and elected officials that address public safety issues pertaining to wildfire along the U.S/Mexico international border. It is a fact that people from other countries have and will continue to enter the United States illegally by crossing from Mexico into the United States. In an effort to stop the flow of illegal immigration, in 1995 the United States government began “Operation Gatekeeper”, in an effort to tighten border security near the city of Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. It instead pushed the crossers to the rugged east of the county and started a new immigration pattern. In desperation, people started entering on foot from the eastern part of Tijuana and without knowing, a trip that formerly took a few hours along the coast, turned into several days and involved a strenuous hike through rugged wilderness. People were not prepared for the summer heat that swelters or the winter where the temperature drops below freezing at the higher elevations. Many of these people simply didn’t understand the difficult conditions they would encounter and this lack of knowledge proved to be life threatening. The Border Agency Fire Council was formally created during the 1996 fire season, with the first meetings conducted in the fall of 1995 due to a dramatic increase in wildfire activity in southeastern San Diego County. -

2 - the Majority (Roughly 94 Percent) of Public Lands Would Be Preserved, Except As Noted in Section 1.2.6

1.2 DESCRIPTION OF SUBAREA The City of San Diego subarea encompasses 206,124 acres within the MSCP study area. The subarea is characterized by urban land uses with approximately three- quarters either built out or retained as open space/park system. The 1997 population within the subarea was approximately 1.3 million. The City of San Diego MHPA represents a “hard line” preserve, in which boundaries have been specifically determined. It is considered an urban preserve which is constrained by existing or approved development, and is comprised of linkages connecting several large areas of habitat. The City's MHPA is approximately 56,831 acres and includes approximately 47,910 acres within City jurisdiction, and additional City-owned lands (8,921 acres) in the unincorporated areas around San Vicente Reservoir, Otay Lakes and Marron Valley (Table 1). The City’s MHPA comprises 29 percent of the regional MHPA and 58 percent of all habitat and vacant lands. The conserved lands within the City’s MHPA total 53 percent of the vacant land in the City (61 percent of total habitat land in City). The City’s MHPA preserves 77 percent of the core biological resource areas and 77 percent of the habitat linkages within its subarea. Lands which are outside of the biological core or linkage areas but are currently dedicated or designated as open space and provide some long term conservation value are included in the City’s MHPA. In addition, a few small holdings of military properties within the City of San Diego have been included in the MHPA. -

Petition to List Souther Calif. and Central Coast Mountain Lions Under CESA

BEFORE THE CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME COMMISSION A Petition to List the Southern California/Central Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) of Mountain Lions as Threatened under the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) A Mountain Lion in the Verdugo Mountains with Glendale and Los Angeles in the background. Photo: NPS Center for Biological Diversity and the Mountain Lion Foundation June 25, 2019 Notice of Petition For action pursuant to Section 670.1, Title 14, California Code of Regulations (CCR) and Division 3, Chapter 1.5, Article 2 of the California Fish and Game Code (Sections 2070 et seq.) relating to listing and delisting endangered and threatened species of plants and animals. I. SPECIES BEING PETITIONED: Species Name: Mountain Lion (Puma concolor). Southern California/Central Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) II. RECOMMENDED ACTION: Listing as Threatened or Endangered The Center for Biological Diversity and the Mountain Lion Foundation submit this petition to list mountain lions (Puma concolor) in Southern and Central California as Threatened or Endangered pursuant to the California Endangered Species Act (California Fish and Game Code §§ 2050 et seq., “CESA”). This petition demonstrates that Southern and Central California mountain lions are eligible for and warrant listing under CESA based on the factors specified in the statute and implementing regulations. Specifically, petitioners request listing as Threatened an Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) comprised of the following recognized mountain lion subpopulations: -

Recovery Plan for Bighorn Sheep in the Peninsular Ranges, California

u.s. Fish & Wildlife Service Recovery Plan for Bighorn Sheep in the Peninsular Ranges, California 010753 010208 Recovery Plan for Bighorn Sheep in the Peninsular Ranges, California U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 1 Approved: Manager, C ia/Nevada Operations Office Region , U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: 010754 010210 The Recovery Plan for Bighorn Sheep in the Peninsular Ranges, California, was developed in cooperation with: Bureau ofLand Management U.S. Forest Service Agua Caliente Band ofCahuilla Indians California Department of Fish and Game California Department ofParks and Recreation Date: ~ Date: IQ41.7./L2Q. Tnbal Chairman, Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians Date: /Pz— 00 Ii.Director. Ca fornia Department Fish and Game _ Date: __________ Director, California Dep yent of Parks and Recrcation 010755 010211 Primary Author The primary author of this recovery plan is: Esther Rubin University of California, Davis Davis, California The plan was written with the assistance ofthe Peninsular Bighom Sheep Recovery Team (see Acknowledgments). i 010756 010212 Disclaimer Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions required to recover andlor protect listed species. We, the Fish and Wildlife Service, publish recovery plans, sometimes preparing them with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State and other Federal agencies, Tribes, and other affected and interested parties. Recovery teams serve as independent advisors to the Fish and Wildlife Service. Objectives ofthe plan will be attained and any necessary funds made available, subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Recovery plans do not obligate cooperating or other parties to undertake specific tasks and may not represent the views nor the official positions or approval ofany individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than our own. -

Appendix F Cultural Resource Evaluation

Otay Hills Construction Aggregate and Inert Debris Engineered Fill Operation Project Appendix F Cultural Resource Evaluation for the Public Review Draft Environmental Impact Report PDS2004-3300-04-004 (MUP); PDS2004-3310-04-001 (RP); PDS2010-3813-10-002 (SPA); Log No. 04-190-04 June 2020 Prepared for: County of San Diego Planning & Development Services 5510 Overland Avenue, Suite 310 San Diego, California 92123 A CULTURAL RESOURCE EVALUATION PROGRAM FOR THE OTAY HILLS QUARRY PROJECT SAN DIEGO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA PDS2010-3813-10-002 (SP); PDS2004-3910-0419004 (ER); PDS2004-3300-04- 004 (P); PDS2004-3310-04-001 (RP); APNs 648-050-12, -13, -14, and -17, and 648-080-13, -14, and -25 Lead Agency: County of San Diego Planning and Development Services 5510 Overland Avenue, Suite 310 San Diego, California 92123 Preparer: Brian F. Smith and Associates, Inc. 14010 Poway Road, Suite A Poway, California 92064 _________________________ Signature Project Proponent: EnviroMINE 3511 Camino Del Rio South, Suite 403 San Diego, California 92108 June 2, 2005; Revised October 26, 2011; Revised November 10, 2014; Revised April 26, 2018 The Otay Hills Quarry Project ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Archaeological Database Information Author(s): Brian F. Smith and Tracy A. Stropes Consulting Firm: Brian F. Smith and Associates, Inc. 14010 Poway Road, Suite A Poway, California 92064 (858) 484-0915 Client/Project Proponent: EnviroMINE 3511 Camino Del Rio South, Suite 403 San Diego, -

Park Summary

2 Existing Conditions (Environmental Setting) 2.1 PARK SUMMARY .................................................................2-3 2.1.1 LAND USE 2-3 2.1.2 FACILITIES 2-3 2.1.3 ADJACENT LAND USE 2-3 2.1.3.1 Native American Land 2-3 2.1.3.2 Federal Land 2-4 2.1.3.3 Other Parks 2-5 2.1.3.4 Other State-Owned Land 2-6 2.1.3.5 Private Operations 2-6 2.1.3.6 International Land 2-8 2.1.3.7 Transportation Corridors 2-8 2.1.4 LAND ACQUISITION 2-9 2.1.5 PARK SUPPORT—ORGANIZATIONS AND VOLUNTEERS 2-9 2.1.5.1 Park Support Organizations 2-9 2.1.5.2 Park Support Volunteers 2-10 2.2 PRIMARY RESOURCES ...................................................... 2-11 2.2.1 PHYSICAL RESOURCES 2-11 2.2.1.1 Topography 2-11 2.2.1.2 Geology 2-12 2.2.1.3 Soils 2-21 2.2.1.4 Meteorology 2-22 2.2.1.5 Hydrology 2-27 2.2.2 BIOTIC RESOURCES 2-31 2.2.2.1 Paleontology 2-31 2.2.2.2 Biota 2-35 2.2.2.3 Sensitive Biota 2-42 2.2.2.4 Exotic Species 2-57 2.2.3 CULTURAL RESOURCES 2-61 2.2.3.1 Prehistoric and Ethnographic Overview 2-61 2.2.3.2 Historical Summary 2-69 2.2.3.3 Designated Historical Resources 2-76 2.2.4 AESTHETIC RESOURCES 2-78 2.2.4.1 Special Qualities 2-79 2.2.5 INTERPRETIVE AND EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES 2-81 2.2.5.1 Facilities 2-82 2.2.5.2 Personal Interpretive Programming 2-82 2.2.5.3 Non-Personal Interpretive Programming 2-83 2.2.6 COLLECTIONS RESOURCES 2-84 2.2.6.1 Introduction 2-84 2.2.6.2 Major Interpretive Themes, Topics, and/or Periods of the Collection 2-84 2.2.6.3 Collection History 2-85 2.2.6.4 Collection Content Summary 2-86 2.2.6.5.Uses of the Collection 2-87 2.2.6.6 Relationship of Collection to Other State Parks and Non-State Park Institutions 2-87 2.2.7 RECREATIONAL RESOURCES 2-88 2.2.7.1 The Visitor Experience 2-88 2.2.7.2 Current Visitor Information 2-88 2.2.7.3 Recreational Infrastructure 2-89 2.3 PLANNING INFLUENCES...................................................2-93 2.3.1 SYSTEM-WIDE PLANNING INFLUENCES 2-93 2.3.2 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT DIRECTIVES 2-93 2.3.3 REGIONAL PLANNING INFLUENCES 2-94 2.3.3.1 Regional Plans 2-94 2.3.3.2 U.S. -

Federal Register/Vol. 71, No. 152/Tuesday, August 8, 2006

44980 Federal Register / Vol. 71, No. 152 / Tuesday, August 8, 2006 / Proposed Rules habitat. However, the legally binding DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR finding is to be made within 90 days of duty to avoid destruction or adverse receipt of the petition, and the finding modification of critical habitat rests Fish and Wildlife Service is to be published in the Federal squarely on the Federal agency. Register. Furthermore, to the extent that non- 50 CFR Part 17 This finding summarizes information Federal entities are indirectly impacted included in the petition and information because they receive Federal assistance Endangered and Threatened Wildlife available to us at the time of the petition or participate in a voluntary Federal aid and Plants; 90-Day Finding on a review. A 90-day finding under section program, the Unfunded Mandates Petition To List the Thorne’s Hairstreak 4(b)(3)(A) of the Act and § 424.14(b) of Reform Act would not apply; nor would Butterfly as Threatened or Endangered our regulations is limited to a critical habitat shift the costs of the large AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, determination of whether the entitlement programs listed above on to Interior. information in the petition meets the ‘‘substantial information’’ threshold. State governments. ACTION: Notice of 90-day petition Substantial information is ‘‘that amount finding. (b) As discussed in the draft economic of information that would lead a analysis of the proposed designation of SUMMARY: reasonable person to believe that the critical habitat for the ABM, the impacts We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), announce a measure proposed in the petition may on nonprofits and small governments be warranted’’ (50 CFR 424.14(b)). -

PROCEEDINGS San Diego Society of Natural History

The Scarabaeoid Beetles of San Diego County, California PROCEEDINGS of the San Diego Society of Natural History Founded 874 Number 40 February 2008 The Scarabaeoid Beetles of San Diego County, California Part I. Introduction and Diagnosis of Families Glaresidae, Trogidae, Pleocomidae, Geotrupidae, Ochodaeidae, Hybosoridae, and Glaphyridae Ron H. McPeak P.O. Box 2136, Battle Ground, WA 98604, U.S.A.; [email protected] Thomas A. Oberbauer County of San Diego Department of Planning and Land Use, 5201 Ruffin Road, Suite B, San Diego, CA 92123, U.S.A.; [email protected] ABSTRACT.—Scarabaeoid beetles are diverse in San Diego County, California, with 8 families, 53 genera, and approximately 50 species repre- sented. Vegetation communities in the county are likewise diverse and directly responsible for supporting the diversity of scarab beetles. Part I of the Scarabaeoid Beetles of San Diego County, California presents data on 8 species in the following 7 families: Glaresidae (), Trogidae (4), Pleocomidae (2), Geotrupidae (5), Ochodaeidae (3), Hybosoridae (), and Glaphyridae (2). This group of diverse beetles is adapted to a wide variety of terrestrial habitats where they feed upon hair, feathers, carrion, other decomposing organic matter, and plants. INTRODUCTION COLLECTING IN SAN DIEGO COUNTY The superfamily Scarabaeoidea is one of the largest groups of Several preeminent beetle taxonomists spent time collecting beetles, containing approximately 2200 genera and 3,000 species in San Diego County during the 9th century (Essig 93). John worldwide (Jameson and Ratcliffe 2002). According to Smith (2003) L. LeConte was in California during 850 while employed as a there are 2 families, approximately 70 genera, and 2000 species in surgeon in the U. -

Smoke Control Analysis of the 114 W

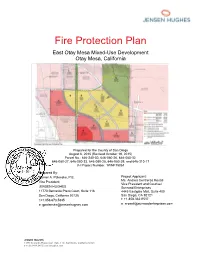

Fire Protection Plan East Otay Mesa Mixed-Use Development Otay Mesa, California Prepared for the County of San Diego August 6, 2015 (Revised October 19, 2015) Parcel No.: 646-240-30, 646-080-26, 646-080-32, 646-080-27, 646-080-33, 646-080-28, 646-080-29, and 646-310-17 JH Project Number. 1WNF15061 Prepared By: Garner A. Palenske, P.E. Project Applicant: Ms. Andrea Contreras Rosati Vice President Vice President and Counsel JENSEN HUGHES Sunroad Enterprises 11770 Bernardo Plaza Court, Suite 116 4445 Eastgate Mall, Suite 400 San Diego, California 92128 San Diego, CA 92121 t:+1.858.673.5845 t: +1.858.362.8537 e: [email protected] e: [email protected] JENSEN HUGHES 11770 Bernardo Plaza Court, Suite 116 | San Diego, California 92128 t +1.619.488.9810| jensenhughes.com Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. Project Location, Description, & Environmental Setting 1 1.1.1. Project Location 1 1.1.2. Project Description 4 1.1.3. Environmental Setting 5 1.1.3.1. On-Site and Surrounding Land Uses 5 1.1.3.2. Trail and Bike Routes 7 1.1.3.3. Regional Access 8 1.1.3.5. Fire History 8 1.1.3.6. Topography 11 CHAPTER 2. GUIDELINES FOR THE DETERMINATION OF SIGNIFICANCE 12 CHAPTER 3. ANTICIPATED FIRE BEHAVIOR IN THE VICINTITY 12 CHAPTER 4. ANALYSIS OF PROJECT EFFECTS 13 4.1. Adequate Emergency Services 13 4.1.1. Fire Jurisdiction & Closest Existing Fire Stations 13 4.1.2. Emergency Response Times of Existing Fire Stations 14 4.2. -

SC IENC E for CON SERVA TION

50-Year Climate Scenarios and Plant Species Distribution Forecasts for Setting Conservation Priorities in Southwestern California October 2013 CONSERVATION for SCIENCE SCIENCE Southwestern California Climate Report – October 2013 50-Year Climate Scenarios and Plant Species Distribution Forecasts for Setting Conservation Priorities in Southwestern California October 2013 Zachary Principe Jason B. MacKenzie Brian Cohen John M. Randall William Tippets Trish Smith Scott A. Morrison The Nature Conservancy of California 201 Mission Street, 4th Floor San Francisco, CA 94105 scienceforconservation.org Contact: John M. Randall, [email protected] Recommended Citation: Principe, Z., J.B. MacKenzie, B. Cohen, J.M. Randall, W. Tippets, T. Smith and S.A. Morrison. 2013. 50-Year Climate Scenarios and Plant Species Distribution Forecasts for Setting Conservation Priorities in Southwestern California v.1. The Nature Conservancy of California, San Francisco, CA. 36 pages + Appendices The Nature Conservancy 2 Southwestern California Climate Report – October 2013 Contents Executive Summary 4 Introduction 5 Study Area 6 Methods 9 Results 15 Recommendations 33 Acknowledgements 35 Appendix 1: Species whose distributions were modeled for this assessment 36 Appendix 2: Abbreviations 38 Appendix 3: Access to Supplemental Material 39 References 40 Figures Figure 1: Study Area 7 Figure 2: USFS ecoregion subsections and survey locations 8 Figure 3: NCCPs/HCPs in the study area 9 Figure 4: Land use categories in the study area 14 Figure 5: Distribution forecast for