An Estimation of Lethal Violence in Casanare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meta River Report Card

Meta River 2016 Report Card c Casanare b Lower Meta Tame CASANARE RIVER Cravo Norte Hato Corozal Puerto Carreño d+ Upper Meta Paz de Ariporo Pore La Primavera Yopal Aguazul c Middle Meta Garagoa Maní META RIVER Villanueva Villavicencio Puerto Gaitán c+ Meta Manacacías Puerto López MANACACÍAS RIVER Human nutrition Mining in sensitive ecosystems Characteristics of the MAN & AG LE GOV E P RE ER M O TU N E E L A N P U N RI C T Meta River Basin C TA V / E ER E M B Water The Meta River originates in the Andes and is the largest I O quality index sub-basin of the Colombian portion of the Orinoco River D I R V E (1,250 km long and 10,673,344 ha in area). Due to its size E B C T R A H A Risks to S S T and varied land-uses, the Meta sub-basin has been split I I L W T N HEA water into five reporting regions for this assessment, the Upper River Y quality EC S dolphins & OSY TEM L S S Water supply Meta, Meta Manacacías, Middle Meta, Casanare and Lower ANDSCAPE Meta. The basin includes many ecosystem types such as & demand Ecosystem the Páramo, Andean forests, flooded savannas, and flooded Fire frequency services forests. Main threats to the sub-basin are from livestock expansion, pollution by urban areas and by the oil and gas Natural industry, natural habitat loss by mining and agro-industry, and land cover Terrestrial growing conflict between different sectors for water supply. -

1 ¿Qué Es La Cartografía Social?

1 ¿QUÉ ES LA CARTOGRAFÍA SOCIAL? Esta herramienta para construir conocimiento colectivo e integral sobre las dinámicas sociales que se expresan sobre determinada zona es de utilidad para identificar las relaciones sociales, conflictos y oportunidades. 2 ¿CÓMO SE DESARROLLA? Usted deberá responder las preguntas que se realizan a continuación dibujándolas y escribiéndolas sobre una plantilla de mapa. De manera posterior el equipo de Indepaz integrará las cartografías de las personas participantes del taller en una sola y así se construirá una gran cartografía sobre el panorama de la industria de la palma en los departamentos de Meta y Casanare. 3 PREGUNTAS A RESPONDER 1. ¿Dónde están las empresas de palma: plantas, oficinas, cultivos, etc.? 2. ¿Qué problemas identifica en su zona entorno a la industria de la palma: sociales y ambientales? 3. ¿Qué oportunidades y soluciones PLANTILLAS DE MAPAS encuentra de acuerdo a los 4 problemas planteados y entorno a la A continuación se encuentran una serie de mapas base industria de la palma? sobre los cuales usted podrá dibujar la respuesta a las preguntas del punto 3 de esta guía. Los mapas están organizados por departamentos (Meta y Casanare) y regiones; y, contienen información básica como ayuda de ubicación: ríos y vías principales. Usted puede imprimir el mapa que le interese y dibujar sobre él o usarlos como quía para dibujar uno nuevo. A. Departamento del Meta CUNDINAMARCA CASANARE Barranca San Juanito de Upía v El Calvario Cabuyaro Cumaral Restrepo Villavicencio Puerto López Acacias Puerto Gaitán Guamal Cubarral Castilla la San Carlos de Nueva Guaroa VICHADA El Dorado Lejanías El Castillo Granada San Martín Fuente de Oro Mesetas San Juan de Arama Puerto Lleras HUILA La Uribe Mapiripán Puerto Puerto Rico Vista Hermosa Concordia La Macarena GUAVIARE CAQUETÁ A-1. -

Dr.5 Clasificacion Geologica

880000,000000 920000,000000 960000,000000 1000000,000000 1040000,000000 1080000,000000 1120000,000000 È CLASIFICACION GEOLOGICA LA SALINA 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 HATO COROZAL 0 0 0 0 0 , () , 0 0 0 SACAMA PUERTO BRASILIA 0 0 0 () 0 SAN LUIS DEL ARIPORO LA COLOMBINA 0 6 6 1 1 P LA MOTUZ P 1 MONTAÑAS DEL TOTUMO 1 ( ) MORICHALES SANTA MARTA RESGUARDO INDIGENA T P VARSOVIA LA POTOSI P LA PERAL K PALOSANTAL SABANETAS EL PORVENIR ( LA AGUA) DA CARRASTOLLA BENDICION DE LOS TRONCOS TAMARA LA PALMITA P LA PALMAJAGUP ITO BARRANCALA ESPERANZA LA UNION CANDELARIA ALTA ( LAS GUAMAS ) LA CANDELARIA TEN LLANO LAS MERCEDES LOS CAMORUCOS EL MUESE LA MESA BRISAS DEL BEBEDERO CAÑADOTES ( ) PAZ DE ARIPORO P ELVECIA P LAS GAVIOTAS Qa RINCON HONDO LA VEREMOS 0 EL DESIERTO 0 BRITO ALTO 0 EL CARIBE 0 0 LABRANCITAS 0 0 0 0 RISARALDA AGUAS CLARAS 0 0 0 , CANALETE , 0 SAN JOSE DE LA LOPERA 0 0 LA LIBERTAD 0 0 NORMANDIA 0 CAÑO CHIQUITO 0 PORE 0 2 2 1 EL BORALPLAYITAS 1 1 1 LA HERMOSA LA SOLEDAD CÑ GARZA CENTRO GAITAN NUNCHIA MANIROTES SAN ESTEBAN CONVE NCIONES LIMITE MUN IC IPAL Suelo Ur bano LIMITE VEREDAL Hi drog ra fía Curv as de Nivel Quebrada Cas as Lago - M oric hal - Es tero Unidad Vias PLAYO N PAVIM ENTADA GEOLOGIA Localización en los sectores de las veredas de : Caracteristcas AREA (Has) RIO Cartografica CARRETEABLE Pantano CAMINO- SENDER O - TRO CHA 0 MANIROTES,LA SOLEDAD CAÑADA GARZA,SAN ESTEBAN,CENTRO GAITAN,EL 0 LOCALIZACIÓN GENERAL 0 BORAL,PLAYITAS,LA ,HERMOSA,LA LIBERTAD,SAN JOSE DE LA LOPERA,CANALETE,EL MAPA DR_5: 0 0 CARIBE,CAÑO CHIQUITO,LABRANCITAS,BRITO ALTO,NORMANDIA,LAS CLASIFICACION GEOLOGICA 0 0 0 0 GAVIOTAS,ELVECIA,LA MESA,RINCON ,HONDO,LA ESPERANZA,CAÑADOTES,TEN Escala Salida 0 Deposito de ladera, 0 1.3520.700 5.400 8.100 10.800 0 LLANO,BRISAS DEL BEBEDERO,EL MUESE,LA VEREMOS,JAGUITO,BARRANCA,EL 0 , Abanicos alubiales, Qa Meters , Sedimentaria-Cenozoica-Q DESIERTO,PALOSANTAL,LA PALMITA,LA BENDICION DE LOS ,RONCOS,CARRASTOL,LA Qa 1180000 1:1.021.778 0 Incluyen fluj o de lodo. -

BPXC's Operations in Casanare, Colombia

Paper Number 31 July 1999 BPXCs Operations in Casanare, Colombia: Factoring social concerns into development decisionmaking Aidan Davy Kathryn McPhail Favian Sandoval Moreno Social Development Papers Paper Number 31 July 1999 BPXCs Operations in Casanare, Colombia: Factoring social concerns into development decisionmaking Aidan Davy Kathryn McPhail Favian Sandoval Moreno This publication was developed and produced by the Social Development Family of the World Bank. The Environment, Rural Development, and Social Development Families are part of the Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development (ESSD) Network. The Social Development Family is made up of World Bank staff working on social issues. Papers in the Social Development series are not formal publications of the World Bank. They are published informally and circulated to encourage discussion and comment within the development community. The findings, interpretations, judgments, and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and should not be attributed to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or to members of the Board of Executive Directors or the governments they represent. Copies of this paper are available from: Social Development The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 USA Fax: 202-522-3247 E-mail: [email protected] Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 7 Aims and Objectives 7 Approach 8 Project Location 8 Main Issues to Factor into the Evaluation 9 Route Map to the Report 9 2. An Evolving Social and Environmental Context 11 Description of BPXCs Operations 11 The Environmental Context of BPXCs Operations 13 The Social Context of BPXCs Operations 13 Key Stakeholders and Their Interactions 13 The Evolving Demographic and Socioeconomic Context 16 Conflict in Casanare 19 3. -

ESTMA Identification Number E798884 Amended Report

Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act - Annual Report Reporting Entity Name Parex Resources Inc. Reporting Year From 2020-01-01 To: 2020-12-31 Date submitted 2021-05-26 Original Submission Reporting Entity ESTMA Identification Number E798884 Amended Report Other Subsidiaries Included (optional field) Not Consolidated Not Substituted Attestation Through Independent Audit In accordance with the requirements of the ESTMA, and in particular section 9 thereof, I attest that I engaged an independent auditor to undertake an audit of the ESTMA report for the entity(ies) and reporting year listed above. Such an audit was conducted in accordance with the Technical Reporting Specifications issued by Natural Resources Canada for independent attestation of ESTMA reports. The auditor expressed an unmodified opinion, dated YYYY-MM-DD, on the ESTMA Report for the entity(ies) and period listed above. The independent auditor's report can be found at Calgary. Full Name of Director or Officer of Reporting Entity Kenneth G. Pinsky Date 2021-05-26 Position Title Chief Financial Officer Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act - Annual Report Reporting Year From: 2020-01-01 To: 2020-12-31 Reporting Entity Name Parex Resources Inc. Currency of the Report USD Reporting Entity ESTMA Identification E798884 Number Subsidiary Reporting Entities (if necessary) Payments by Payee Departments, Agency, etc… Infrastructure Total Amount paid to Country Payee Name within Payee that Received Taxes Royalties Fees Production Entitlements Bonuses Dividends Notes Improvement -

Construcción De Una Línea Base Para La Medición Del Impacto De La Educación Superior Rural En La Colombia Profunda

Revista de la Universidad de La Salle Volume 2014 Number 64 Article 8 January 2014 Construcción de una línea base para la medición del impacto de la educación superior rural en la Colombia profunda Miguel Darío Sosa Rico Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, [email protected] Luis Alejandro Taborda Andrade Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ciencia.lasalle.edu.co/ruls Citación recomendada Sosa Rico, M. D., y L.A. Taborda Andrade (2014). Construcción de una línea base para la medición del impacto de la educación superior rural en la Colombia profunda. Revista de la Universidad de La Salle, (64), 155-173. This Artículo de Revista is brought to you for free and open access by the Revistas de divulgación at Ciencia Unisalle. It has been accepted for inclusion in Revista de la Universidad de La Salle by an authorized editor of Ciencia Unisalle. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Construcción de una línea base para la medición del impacto de la educación superior rural en la Colombia profunda Miguel Darío Sosa Rico* Luis Alejandro Taborda Andrade** Resumen Utopía es un Programa de la Universidad de La Salle que genera opor- tunidades de educación para los jóvenes de los sectores rurales de Colombia. El presente documento tiene como objetivo hacer una des- cripción general de las dinámicas económicas de las zonas de origen de los estudiantes del Programa, con el fin de hacer una primera aproxima- ción a la línea base para la construcción de la metodología de medición de su impacto. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

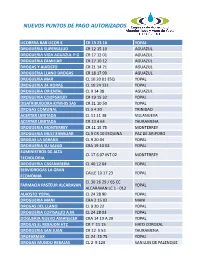

NUEVOS PUNTOS DE PAGO AUTORIZADOS LICORERA BAR LICOR S CR 19 23 10 YOPAL DROGUERIA SUPERSALUD CR 12 15 10 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA VIDA AGUAZUL P G CR 17 12 01 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA FAMILIAR CR 17 10 12 AGUAZUL DROGAS Y ALKOSTO CR 21 14 71 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA LLANO DROGAS CR 18 17 99 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA MAR CL 10 20 01 ESQ YOPAL DROGUERIA 24 HORAS CL 10 24 131 YOPAL DROGUERIA ORIENTAL CL 9 14 38 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA COOPSALUD CR 19 15 32 YOPAL DISATRIBUIDORA KYWHIS SAS CR 21 10 50 YOPAL DROGAS COMUNAL CL 5 4 20 TRINIDAD ACERTAR LIMITADA CL 11 11 38 VILLANUEVA ACERTAR LIMITADA CR 13 4 64 TAURAMENA DROGUERIA MONTERREY CR 11 15 75 MONTERREY DROGUERIA MULTIFAMILIAR CL 9 CR 10 ESQUINA PAZ DE ARIPORO DROGAS LA SABANA CL 9 20 04 YOPAL DROGUERIA SU SALUD CRA 19 10 02 YOPAL SUMINISTROS DE ALTA CL 17 6 07 INT 02 MONTERREY TECNOLOGIA DROGUERIA CASANAREÑA CL 40 12 04 YOPAL SERVIDROGAS LA GRAN CALLE 10 17 23 YOPAL ECONOMIA CL 30 26 29 / 65 CC FARMACIA PASTEUR ALCARAVAN YOPAL ALCARAVAN LC 1 - 012 ALKOSTO YOPAL CL 24 28 90 YOPAL DROGUERIA MANI CRA 2 15 02 MANI DROGAS DEL LLANO CL 9 20 22 YOPAL DROGUERIA COPISALUD A.M. CL 24 28 03 YOPAL DOGUERIA NUEVO AMANECER CRA 14 19 A 20 YOPAL DROGAS EL REBAJON HTZ CR 7 11 15 HATO COROZAL DROGUERIA SAN JUAN CR 12 5 53 TAURAMENA DROFARMAX CL 24 25 75 YOPAL DROGAS MUNDO REBAJAS CL 2 9 123 SAN LUIS DE PALENQUE NUEVOS PUNTOS DE PAGO AUTORIZADOS DROGUERIA ANFREX SALUD CL 16 21 05 YOPAL DROGUERIA COLFAM CL 15 17 67 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA SU SALUD 2 CL 9 16 29 AGUAZUL DROGUERIA SAN JUAN CARRERA 16 # 36B-26 YOPAL CASANARE BRR EL PORTAL DROGUERIA -

Missing People in Casanare

Missing People in Casanare Daniel Guzmán, Tamy Guberek, Amelia Hoover, and Patrick Ball November 28, 2007 1 Introduction How many people are missing in the department of Casanare, Colombia? This apparently simple question proves complex when we ask how many missing persons were not reported to any organization, and becomes even more difficult in the context of politically contentious debates about exhumation, identification and reunification of remains. How can we be sure that all the missing are accounted for in some way? How should we approach the problem of searching for victims? Answers to these and other questions will be incorrect if we assume that any list or combination of lists is “comprehensive.” Ultimately, correct answers rely on scientific estimation of the number of missing persons. In this initial analysis, we estimate that the total number of missing persons in Casanare 1986-2007 is 2,553.1 Approximately 1,500 persons were reported missing during this period, yielding an “undocumented rate” of about 40% (of total estimated missing persons). We emphasize that the rate of undocumented missing persons found in Casanare does not necessarily represent the rate that could be found in Colombia more generally, if data were available. We recom- mend that additional data should be gathered and made available for analysis by statisticians and social scientists. Furthermore, this analysis demonstrates that no single list of missing persons estimates the total number of persons likely to be missing in Casanare. We proceed in several sections. First, we outline our findings. Then we con- sider the available data on Casanare from thirteen data collection projects. -

“La Corocora” Alza El Vuelo En Investigación Para El Casanare

Investigación - Fedearroz - Fondo Nacional del Arroz 28 “LA COROCORA” ALZA EL VUELO EN INVESTIGACIÓN PARA EL CASANARE Ph. D. Mario Sandoval C* M. Sc. Jose Omar Ospina G* Ing. Juan Carlos Diaz* Ing. Jorge Ardila Cuevas * *Investigador y transferidor FEDEARROZ- Fondo Nacional del Arroz-FNA. La Corocora, nombre que identifica una de las aves más hermosas y representativas de los Llanos Orientales, lo es también de la granja que será modernizada y tecnificada como uno de los componentes centrales del proyecto de investigación, que con el objetivo de obtener variedades de arroz específicas para el departamento de Casanare, ha empezado a ser desarrollado como resultado de los esfuerzos compartidos entre Fedearroz, La gobernación, la alcaldía de Aguazul y la Universidad Unitrópico. Es el punto de partida de un gran Centro Experimental para el arroz en ese departamento, que es hoy el mayor productor del grano en el país y que le permitirá avanzar en los diferentes aspectos agronómicos de este cultivo. El siguiente artículo, hace un recorrido por los antecedentes y los diferentes aspectos puntuales del proyecto que ya está en ejecución. Vol. 66 - Noviembre - Diciembre 2018 Investigación - Fedearroz - Fondo Nacional del Arroz 29 ¿Como inició el proyecto? • Programa de Genética: Con los subprogramas de Fitomejoramiento convencional y Biotecnología. Hoy en día uno de los principales desafíos lo constituye el cambio • Programa de Agronomía: Con los subprogramas de climático que ejerce presión sobre la genética de las plantas y Fisiología de la producción y Manejo Integrado de Plagas la capacidad productiva de las tierras agrícolas afectando el (Malherbología, Insectos, Enfermedades) crecimiento económico agrícola de las regiones. -

Disponibilidad Hídrica, Cambio Climático Y Configuraciones Territoriales En Tauramena, Casanare

DISPONIBILIDAD HÍDRICA, CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO Y CONFIGURACIONES TERRITORIALES EN TAURAMENA, CASANARE IVONNE ANGÉLICA MONTAÑA MOLINA UNIVERSIDAD EXTERNADO DE COLOMBIA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y HUMANAS ÁREA DE DEMOGRAFÍA Y ESTUDIOS DE POBLACIÓN BOGOTÁ D.C. 2019 DISPONIBILIDAD HÍDRICA, CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO Y CONFIGURACIONES TERRITORIALES EN TAURAMENA, CASANARE IVONNE ANGÉLICA MONTAÑA MOLINA Trabajo de grado presentado como requisito para optar al título de: Magíster en Planeación Territorial y Dinámicas de Población Asesores: Norma Rubiano Orlando Velazco Docentes Área de Demografía y Estudios de Población Proyecto Marco: Planeación Territorial, Dinámicas Poblacionales Y Cambio Climático UNIVERSIDAD EXTERNADO DE COLOMBIA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y HUMANAS CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS SOBRE DINÁMICA SOCIAL (CIDS) ÁREA DE DEMOGRAFÍA Y ESTUDIOS DE POBLACIÓN BOGOTÁ D.C. 2019 1 AGRADECIMIENTOS En primer lugar, agradezco a la vida por los distintos caminos que me han llevado a la Universidad Externado, pues allí no sólo he crecido como profesional y ahora magíster, sino que he crecido como una persona con conciencia ético-política crítica y un compromiso hacia la transformación que incorpora al ser y trasciende al colectivo. Agradezco a la doctora Lucero Zamudio (Q.E.P.D.) y a los docentes del área de Demografía y Estudios de Población, especialmente al equipo que desarrolla BIT-PASE: Norma Rubiano, Alejandro González, Juan Andrés Castro, Orlando Velasco y Rafael Navarro; ellas y ellos me han brindado las oportunidades para aprender en un entorno de crecimiento pleno, personal e intelectual. Agradezco infinitamente a mis padres, Alicia Molina y Fernando Montaña, quienes han dado absolutamente todo de sí mismos para apoyarme incondicionalmente en el cumplimiento de mis objetivos. -

Algunos Indicadores Sobre La Situación De Los Derechos Humanos En El Departamento De Casanare

Actualizado a marzo de 2005 ALGUNOS INDICADORES SOBRE LA SITUACIÓN DE LOS DERECHOS HUMANOS EN EL DEPARTAMENTO DE CASANARE DEDEPARTAMENTO DE CASANARE El departamento del Casanare es hoy un complejo escenario de la confrontación armada por el accionar de los grupos guerrilleros y en especial, de autodefensa. Las condiciones geográficas y económicas del departamento han convertido su territorio en una zona estratégica para los grupos al margen de la ley que se disputan su dominio. Casanare presenta estribaciones de la cordillera occidental aunque se encuentra ubicado en los llanos orientales del país. Limita con Arauca en el norte, Boyacá en el occidente y, Vichada y Meta en el suroriente y en el sur, departamentos que desde hace varias décadas han tenido una alta actividad armada por parte de los grupos insurgentes y de autodefensa. Topográficamente, Casanare tiene una parte montañosa en su parte occidental y un terreno plano en el centro y en el sector oriental, situación que favorece la presencia y movilidad de los grupos de guerrilla y autodefensa. La incursión de los grupos de autodefensa y de guerrilla tiene sus raíces en los reductos de la violencia de los años cincuenta. En 1980, las FARC OBSERVATORIO DEL PROGRAMA PRESIDENCIAL DE DERECHOS 1 HUMANOS Y DIH Actualizado a marzo de 2005 mostraban una incipiente presencia en este departamento, sin embargo alrededor de la década de los noventa, motivadas por objetivos estratégicos de expansión territorial, consignados en las conclusiones de su Séptima Conferencia (1982) y sus intereses en torno al dominio de la cordillera oriental, al auge petrolero y al fortalecimiento del narcotráfico, posiciona en esta zona dos de sus frentes pertenecientes al bloque Oriental. -

Transformaciones Económicas Y Sociales En Las Juntas De

TRANSFORMACIONES ECONÓMICAS Y SOCIALES EN LAS JUNTAS DE ACCIÓN COMUNAL A CAUSA DE LA INDUSTRIA PETROLERA EL CASO DE LA VEREDA EL BANCO BUENOS AIRES, HATOCOROZAL, CASANARE Anderson Zamir Rojas Cortázar Directora Olga Lucía Castillo Ospina Maestría Desarrollo Rural Facultad de Estudios Ambientales y Rurales Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Octubre 31 de 2017 Bogotá, Colombia Tabla de Contenidos Capítulo Uno - Introducción y Planteamiento del Problema .............................. 5 1.1 Problema de Investigación .................................................................. 7 1.2 Aspectos metodológicos .................................................................... 12 Capítulo Dos - Algunas características de la Zona de Estudio .......................... 16 2.1 Breve historia territorial y poblacional del municipio .............................. 16 2.2 La Junta de Acción Comunal (JAC) de la vereda El Banco de Buenos Aires 18 2.3 Acceso a servicios públicos ................................................................ 19 2.4 Estructura ecológica ......................................................................... 21 Capítulo Tres - La industria petrolera en el Departamento del Casanare ........... 23 3.1 Los inicios de la explotación petrolera en el Casanare ............................ 23 3.2 La reforma del sistema de regalías y la corrupción ................................ 25 3.3 La relación de la industria petrolera con el conflicto armado ................... 31 Capítulo Cuatro - Estado del Arte ...............................................................