Behind the Scenes: Somalia and Rwanda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The UN and the Bretton Woods Institutions

The UN and the Bretton Woods Institutions New Challenges for the Twenty-First Century Edited by Mahbub ul Haq Special Adviser to UNDP Administrator New York Richard Jolly Deputy Executive Director UNICEF Paul Streeten Emeritus Professor Boston University and Khadija Haq Executive Director North South Roundtable New York Contents Preface List of Abbreviations Conference Participants and Contributors Part 1 Overview Part II The Bretton Woods System I An Historical Perspective H. W Singer 2 The Vision and the Reality Mahhub ul Hag 3 A Changing Institution in a Changing World Alexander Shakoes 4 The Keynesian Vision and the Developing Countries La! Jayawardena 5 An African Perspective on Bretton Woods Adebayo Adedeji A West European Perspective on Bretton Woods Andrea Boltho Part III Reforms in the UN and the BreROn Woods Institutions 7 A Comparative Assessment Catherine Gwin 8 A Blueprint for Reform Paul Streeten A New International Monetary System for the Futu Carlos Massad 10 On the Modalities of Macroeconomic Policy Coordination John Williamson Part IV Priorities for the Twenty-first Century I I Gender Priorities for the Twenty-first Century Khadija Haq 12 Biases in Global Markets: Can the Forces of Inequity and Marginalization be Modified? Frances Stewart 13 Poverty Eradication and Human Development: Issues for the Twenty-first Century Richard folly 14 Role of the Multilateral Agencies after the Earth Summit Maurice Williams 15 New Challenges for Regulation of Global Financial Markets Stephany Griffith-Jones 16 A New Framework for Development Cooperation Mahbub ul Hay Preface With the end of the cold war, the United Nations is experiencing a new lease on life. -

The International Response to Conflict and Genocide:Lessom from the Rwanda Experience

The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience March 1996 Published by: Steering Committee of the Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda Editor: David Millwood Cover illustrations: Kiure F. Msangi Graphic design: Designgrafik, Copenhagen Prepress: Dansk Klich‚, Copenhagen Printing: Strandberg Grafisk, Odense ISBN: 87-7265-335-3 (Synthesis Report) ISBN: 87-7265-331-0 (1. Historical Perspective: Some Explanatory Factors) ISBN: 87-7265-332-9 (2. Early Warning and Conflict Management) ISBN: 87-7265-333-7 (3. Humanitarian Aid and Effects) ISBN: 87-7265-334-5 (4. Rebuilding Post-War Rwanda) This publication may be reproduced for free distribution and may be quoted provided the source - Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda - is mentioned. The report is printed on G-print Matt, a wood-free, medium-coated paper. G-print is manufactured without the use of chlorine and marked with the Nordic Swan, licence-no. 304 022. 2 The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience Study 2 Early Warning and Conflict Management by Howard Adelman York University Toronto, Canada Astri Suhrke Chr. Michelsen Institute Bergen, Norway with contributions by Bruce Jones London School of Economics, U.K. Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda 3 Contents Preface 5 Executive Summary 8 Acknowledgements 11 Introduction 12 Chapter 1: The Festering Refugee Problem 17 Chapter 2: Civil War, Civil Violence and International Response 20 (1 October 1990 - 4 August -

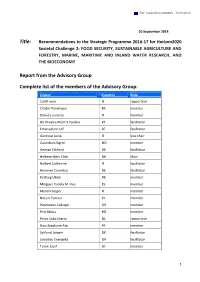

Report from the Advisory Group Complete List of the Members of the Advisory Group

Ref. Ares(2014)3390685 - 14/10/2014 30 September 2014 Title: Recommendations to the Strategic Programme 2016-17 for Horizon2020 Societal Challenge 2: FOOD SECURITY, SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE AND FORESTRY, MARINE, MARITIME AND INLAND WATER RESEARCH, AND THE BIOECONOMY Report from the Advisory Group Complete list of the members of the Advisory Group: Expert Country Role Cahill Jean IE rapporteur Chable Veronique FR member Daroda Lorenza IT member De Oliveira Mont S.Paulina PT facilitator Emanuelson Ulf SE facilitator Gardossi Lucia IT vice chair Gaseidnes Sigrid NO member George Eckhard DE facilitator Halberg Niels Chair DK chair Halbert Catherine IE facilitator Hammer Cornelius DE facilitator Kettling Ulrich DE member Minguez Tudela M. Ines ES member Morelli Sergio IT member Nocun Tomasz PL member Panoutsou Calliope GR member Pele Maria RO member Perez Soba Marta NL rapporteur Riou Stephane Alai FR member Schlund Jorgen DK facilitator Sossidou Evangelia GR facilitator Turok Jozef SK member 1 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 1 SUSTAINABLE AND COMPETITIVE AGRI-FOOD SECTOR FOR A SAFE AND HEALTHY DIET............................. 10 2 SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE AND FORESTRY .............................................................................................. -

UNITED NATIONS Tthef NATIONS UNIES

UNITED NATIONS ttHEf NATIONS UNIES THE SECRETARY-GENERAL Message to the United Nations International Meeting in support of a Peaceful Settlement of the Question of Palestine and the Establishment of Peace in the Middle East Delivered by Mr. Peter Hansen, Commissioner-General, UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East Athens. 23-24 Mav 2000 It gives me pleasure to convey my greetings to all who have gathered in Athens for this important international meeting. I would like to pay tribute to the Government and people of Greece for hosting this event and assisting in its preparation. You come together at a particularly sensitive and difficult stage of the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. The parties are making a determined effort to overcome decades of suspicion and animosity. They are addressing issues of paramount importance, including refugees, Jerusalem, settlements, borders and the sharing of water resources. They are attempting to build bridges of trust, partnership and understanding. The United Nations continues to play an active role in supporting this process, in particular by helping to lay the economic and social foundations for a viable peace. These efforts have focused on developing Palestinian infrastructure, enhancing institutional capacity and improving the living conditions of the Palestinian people. Indeed, for more than half a century the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East has provided humanitarian assistance and essential basic services. I would like to take this opportunity to call again on donors to provide UNRWA with the resources it needs to keep up with the growth and rising needs of the refugee community. -

1980 UN Yearbook

Structure of the United Nations 1399 Principal members of the United Nations Secretariat (as at 31 December 1980) Secretariat Economic Commission for Latin America Under-Secretary-General, Executive Secretary: Enrique V. The Secretary-General: Kurt Waldheim lgiesias Executive Office of the Secretary-General Economic Commission for Africa Under-Secretary-General, Chef de Cabinet: Rafeeuddin Under-Secretary-General, Executive Secretary: Adebayo Ahmed Adedeji Office of the Director-General for Development Economic Commission for Western Asia end International Economic Co-operation Under-Secretary-General, Executive Secretary: Mohamed- Director-General: K. K. S. Dadzie Said Al-Attar Office of the Under-Secretaries-General Centre for Science and Technology for Development for Special Political Affairs Assistant Secretary-General, Executive Director: Amilcar F. Under-Secretary-General: Javier Pérez de Cuéllar Ferrari Under-Secretary-General: Brian E. Urquhart United Nations Centre for Human Settlements Office for Special Political Questions Under-Secretary-General, Executive Director: Arcot Under-Secretary-General, Co-ordinator, Special Economic Ramachandran Assistance Programmes: Abdulrahim Abby Farah Assistant Secretary-General, Joint Co-ordinator, Unit for United Nations Centre on Transnational Corporations Special Economic Assistance Programmes: Gordon K. Assistant Secretary-General, Executive Director: Klaus Aksel Goundrey Sahlgren Office of the Under-Secretary-General for Department of Administration, Finance and Management Political and General Assembly Affairs Under-Secretary-General: Helmut F. Debatin Under-Secretary-General: William B. Buffum Assistant Secretary-General, Special Representative of the OFFICE OF FINANCIAL SERVICES Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs in South-East Assistant Secretary-General: Patricia Ruedas Asia: M'Hamed Essaafi OFFICE OF PERSONNEL SERVICES Office of Secretariat Services for Assistant Secretary-General: James O. -

Leading Change in United Nations Organizations

Leading Change in United Nations Organizations By Catherine Bertini Rockefeller Foundation Fellow June 2019 Leading Change in United Nations Organizations By Catherine Bertini Rockefeller Foundation Fellow June 2019 Catherine Bertini is a Rockefeller Foundation Fellow and a Distinguished Fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. The Rockefeller Foundation grant that supported Bertini’s fellowship was administered by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization that provides insight – and influences the public discourse – on critical global issues. We convene leading global voices, conduct independent research and engage the public to explore ideas that will shape our global future. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs is committed to bring clarity and offer solutions to issues that transcend borders and transform how people, business and government engage the world. ALL STATEMENTS OF FACT AND OPINION CONTAINED IN THIS PAPER ARE THE SOLE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION OR THE CHICAGO COUNCIL ON GLOBAL AFFAIRS. REFERENCES IN THIS PAPER TO SPECIFIC NONPROFIT, PRIVATE OR GOVERNMENT ENTITIES ARE NOT AN ENDORSEMENT. For further information about the Chicago Council on Global Affairs or this paper, please write to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, 180 North Stetson Avenue, Suite 1400, Chicago, IL 60601 or visit thechicagocouncil.org and follow @ChicagoCouncil. © 2019 by Catherine Bertini ISBN: 978-0-578-52905-9 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This paper may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and excerpts by reviewers for the public press), without written permission. -

Crisis, Continuity, and Change in International Investment Law and Arbitration

Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 42 Issue 2 2021 Crisis, Continuity, and Change in International Investment Law and Arbitration Valentina Vadi Lancaster University Law School, United Kingdom Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Valentina Vadi, Crisis, Continuity, and Change in International Investment Law and Arbitration, 42 MICH. J. INT'L L. 321 (2021). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol42/iss2/4 https://doi.org/10.36642/mjil.42.2.crisis This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRISIS, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGE IN INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT LAW AND ARBITRATION Valentina Vadi* “Strive not Leuconoe! To know what end The gods above to me, or thee, will send. Whilst we are talking, envious time doth slide, This day’s thine own, the next may be deny’d.”1 “All things hang like a drop of dew upon a blade of grass.”2 I. INTRODUCTION Can international law embrace the fluidity of time and successfully manage change? The debate over continuity and change lies at the heart of international law, which seeks to foster peaceful, just, and prosperous rela- tions among nations.3 International law endeavors to govern the future by applying, in the present, the legal heritage of the past. -

IDHA 48 Program 8 June

THE INTERNATIONAL DIPLOMA IN HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE IDHA 48 New York, June 5th – July 2nd, 2016 The Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs (IIHA), Fordham University In Cooperation With: The Center for International Humanitarian Cooperation (CIHC) The Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland June 5, 2016 Dear Friends, I am pleased to offer, once again, the International Diploma in Humanitarian Assistance in New York City. The International Diploma in Humanitarian Assistance (IDHA) is a core program of the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs (IIHA) at Fordham University, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) at Fordham University, and the Center for International Humanitarian Cooperation (CIHC). The Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs (IIHA) was created at Fordham University in December 2001 to forge partnerships with relief organizations, offer rigorous academic and training courses at the graduate and undergraduate level, host symposia, and publish books relating to humanitarian affairs. The Institute enables humanitarian workers to develop relationships with the University and the international community in New York City, in addition to being a university wide center reporting directly to the President of Fordham. With the creation of a graduate Master’s and undergraduate Minor and Major degree programs, the Institute offers an academic base for the study and development of international health, human rights, and other humanitarian issues, especially those that occur in periods of conflict. The IIHA trains students for careers in the humanitarian field by combining an advanced academic approach with the shared practical field experience of both students and faculty. It provides consultation on humanitarian affairs to the Fordham community, and the international development community at large. -

EDITORIAL Understanding How International Or- Ganizations

EDITORIAL Understanding How International Or- ganizations Function: Theory, Empirical Analysis, and History by John Mathiason, Cornell Institute for Public Affairs, Cornell University The four articles in this issue of the Journal of International Organizations Studies (JIOS) cover diverse subjects, but their main contribution is in applying different approaches in their analysis. Two apply approaches from international organization theory to understand how regional intergovernmental organizations grow and function—or not; a third uses empirical analysis to determine how national bureaucratic factors influence intergovernmental decision making; and a fourth uses historical analysis to document how the status of women issue transitioned from one international organization to its successor. Each makes a contribution to the literature but also raises questions about the theories employed, the analytical techniques used, and the extent to which history is correctly documented. Malte Brosig’s “Interregionalism at a Crossroads: African–European Crisis Management in Libya—a Case of Organized Inaction?” is an analysis of the role of two intergovernmental organizations, the African Union and the EU, in the international response to political developments connected with Libya’s Arab Spring in 2012. These two organizations, in the author’s words, were “disenfranchised from this conflict despite Libya touching upon vital security interests of their member states.” The article documents how these organizations have developed a joint strategy, as part of interregional cooperation that includes peace and security as one of its pillars. In this sense, interactions between regional intergovernmental bodies are a new approach to achieving joint objectives. Brosig suggests that they, on the basis of the agreed strategy, should have cooperated more effectively in the Libyan situation. -

Transparency in the Selection and Appointment of Senior Managers in the United Nations Secretariat

JIU/REP/2011/2 TRANSPARENCY IN THE SELECTION AND APPOINTMENT OF SENIOR MANAGERS IN THE UNITED NATIONS SECRETARIAT Prepared by M. Deborah Wynes Mohamed Mounir Zahran Joint Inspection Unit Geneva 2011 United Nations JIU/REP/2011/2 Original: ENGLISH TRANSPARENCY IN THE SELECTION AND APPOINTMENT OF SENIOR MANAGERS IN THE UNITED NATIONS SECRETARIAT Prepared by M. Deborah Wynes Mohamed Mounir Zahran Joint Inspection Unit United Nations, Geneva 2011 iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Transparency in the selection and appointment of senior managers in the United Nations Secretariat JIU/REP/2011/2 The report was prepared pursuant to paragraph 19 of General Assembly resolution 64/259, “Towards an accountability system in the United Nations Secretariat”, and will be submitted to the General Assembly at the main part of its sixty-sixth session. The objective of the study was to review the effectiveness, coherence, timeliness and transparency of the current selection and appointment processes of senior managers in the United Nations Secretariat and provide recommendations leading to enhanced transparency. For the purpose of this report, senior managers are defined as the Deputy Secretary-General, Under-Secretaries-General and Assistant Secretaries-General; the scope is limited to the United Nations Secretariat. Main findings and conclusions Member States are familiar with the process as outlined in the Secretary-General’s report on accountability (A/64/640) and for the most part, no major concerns were expressed with the description of the process itself. The concern is with the implementation of the process, which is seen as opaque, raising many questions as to how the process actually works. -

Open Letter to Secretary-General of the United Nations Appointment of the Next Secretary-General of UNCTAD

Open letter to Secretary-General of the United Nations Appointment of the next Secretary-General of UNCTAD 15 January 2013 Dear Mr. Secretary-General, Later this year, you will be nominating to the General Assembly your choice of the next Secretary-General of UNCTAD. The personal attributes of the chief executive of an international organisation are key factors affecting its performance and credibility. Thus the selection is crucial and for that, UNCTAD is no exception, especially at this time of global economic uncertainty. We very strongly urge that the next Secretary-General of UNCTAD, in addition to all the necessary experience, knowledge and management abilities, should have in particular the capacity and courage for independent thought. It is this characteristic that has been the distinguishing factor among the eminent persons who have held the post over nearly 50 years of UNCTAD’s existence. A demonstrated ability to provide strong and independent leadership to global analysis from a development perspective and to promote fresh thinking on trade and development issues is needed today more than ever. The world clamours for innovative economic thinking that charts a sustainable way out of the current crisis and that contributes to development and poverty reduction. We would regard the capacity to stimulate such thinking and to articulate the resulting policy approaches in the relevant forums as the single most important consideration when sifting among possible candidates in the requisite consultations with member States. The growing weight of developing countries in global matters requires an intellectually outstanding personality as the new leader of UNCTAD. The undersigned comprise those from public life and academia who respect the work of UNCTAD in one area or another as well as former UN and UNCTAD staff members who remain committed to its ideals and values. -

The Un and the Bretton Woods Institutions

THE UN AND THE BRETTON WOODS INSTITUTIONS Also by Mahbub ul Haq A STRATEGY OF ECONOMIC PLANNING THE POVERTY CURTAIN SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: FROM CONCEPT TO ACTION NEW PERSPECTIVES ON HUMAN DEVELOPMENT Also by Richard Jolly ADJUSTMENT WITH A HUMAN FACE (co-editor with Andrea Cornia and Frances Stewart) DISARMAMENT AND WORLD DEVELOPMENT EMPLOYMENT, INCOMES AND EQUALITY REDISTRIBUTION WITH GROWTH Also by Paul Streeten DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVES ECONOMIC INTEGRATION FIRST THINGS FIRST THE FRONTIERS OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES WHAT PRICE FOOD? Also by Khadija Haq CRISIS OF THE '80s DIALOGUE FOR A NEW ORDER EQUALITY OF A NEW ORDER EQUALITY OF OPPORTUNITY WITHIN AND AMONG NATIONS HUMAN DEVELOPMENT: THE NEGLECTED DIMENSION (co-editor) THE INFORMATICS REVOLUTION AND THE DEVELOPING COUNTRIES The UN and the Bretton Woods Institutions New Challenges for the Twenty-First Century Edited by Mahbub ul Haq Special Adviser to UNDP Administrator New York Richard Jolly Deputy Executive Director UNICEF Paul Streeten Emeritus Professor Boston University and Khadija Haq Executive Director North South Roundtable New York MMACMillAN © North South Roundtable 1995 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Pa!ents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WIP 9HE. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.