Engineering Design Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roundabout Planning, Design, and Operations Manual

Roundabout Planning, Design, and Operations Manual December 2015 Alabama Department of Transportation ROUNDABOUT PLANNING, DESIGN, AND OPERATIONS MANUAL December 2015 Prepared by: The University Transportation Center for of Alabama Steven L. Jones, Ph.D. Abdulai Abdul Majeed Steering Committee Tim Barnett, P.E., ALDOT Office of Safety Operations Stuart Manson, P.E., ALDOT Office of Safety Operations Sonya Baker, ALDOT Office of Safety Operations Stacey Glass, P.E., ALDOT Maintenance Stan Biddick, ALDOT Design Bryan Fair, ALDOT Planning Steve Walker, P.E., ALDOT R.O.W. Vince Calametti, P.E., ALDOT 9th Division James Brown, P.E., ALDOT 2nd Division James Foster, P.E., Mobile County Clint Andrews, Federal Highway Administration Blair Perry, P.E., Gresham Smith & Partners Howard McCulloch, P.E., NE Roundabouts DISCLAIMER This manual provides guidelines and recommended practices for planning and designing roundabouts in the State of Alabama. This manual cannot address or anticipate all possible field conditions that will affect a roundabout design. It remains the ultimate responsibility of the design engineer to ensure that a design is appropriate for prevailing traffic and field conditions. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1. Purpose ...................................................................................................... 1-5 1.2. Scope and Organization ............................................................................... 1-7 1.3. Limitations ................................................................................................... -

Principles of Design

Principles of Design Balance Proportion/Scale Emphasis Rhythm Introduction The principles of design are essential to the development and production of clothing used by individuals and families around the world. Each principle has a specific role in creating an aesthetically pleasing garment or ensemble. The principles of design consist of: balance, proportion (also referred to as scale), emphasis, and rhythm. When a garment or ensemble uses the elements and principles of design to create a visual unity, harmony is achieved. Garments often integrate more than one principle, while drawing from the elements of design to create a cohesive look. The following discussion will present background information on each of the principles of design and applications to clothing design and construction. Balance According to Wolfe (2011) balance implies that there is an equilibrium or uniformity among the parts of a design (p. 205). To achieve balance, a garment or ensemble should have equal visual weight throughout the design. The use of structural features, added embellishments, or decorations to a garment contribute to the appearance of a garment or ensemble being balanced or not. A clothing designer can utilize surface designs on fabric to construct a garment creating visual balance. Further, color, line, and texture can impact the balance of a design. For example, cool and light colors have less visual weight than dark, warm colors. If an individual is wearing a small amount of a dark, warm color it can be balanced out with a larger amount of cool, light colors. Balance used in clothing design can be categorized into two groups: Formal and Informal Balance. -

New Product Development Methods: a Study of Open Design

New Product Development Methods: a study of open design by Ariadne G. Smith S.B. Mechanical Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2010 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGINEERING SYSTEMS DEVISION AND THE DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREES OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN TECHNOLOGY AND POLICY AND MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING A; SW AT THE <iA.Hu§TTmrrE4 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY H 2 INSTI' SEPTEMBER 2012 @ 2012 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of Author: Department of Engineering Systems Division Department of Mechanical Engineering Certified by: LI David R. Wallace Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Certified by: Joel P. Clark P sor of Materials Systems and Engineering Systems Acting Director, Te iology and Policy Program Certified by: David E. Hardt Ralph E. and Eloise F. Cross Professor of Mechanical Engineering Chairman, Committee on Graduate Students New Product Development Methods: a study of open design by Ariadne G. Smith Submitted to the Departments of Engineering Systems Division and Mechanical Engineering on August 10, 2012 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Technology and Policy and Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering ABSTRACT This thesis explores the application of open design to the process of developing physical products. Open design is a type of decentralized innovation that is derived from applying principles of open source software and crowdsourcing to product development. Crowdsourcing has gained popularity in the last decade, ranging from translation services, to marketing concepts, and new product funding. -

Chapter 3 Software Design

CHAPTER 3 SOFTWARE DESIGN Guy Tremblay Département d’informatique Université du Québec à Montréal C.P. 8888, Succ. Centre-Ville Montréal, Québec, Canada, H3C 3P8 [email protected] Table of Contents references” with a reasonably limited number of entries. Satisfying this requirement meant, sadly, that not all 1. Introduction..................................................................1 interesting references could be included in the recom- 2. Definition of Software Design .....................................1 mended references list, thus the list of further readings. 3. Breakdown of Topics for Software Design..................2 2. DEFINITION OF SOFTWARE DESIGN 4. Breakdown Rationale...................................................7 According to the IEEE definition [IEE90], design is both 5. Matrix of Topics vs. Reference Material .....................8 “the process of defining the architecture, components, 6. Recommended References for Software Design........10 interfaces, and other characteristics of a system or component” and “the result of [that] process”. Viewed as a Appendix A – List of Further Readings.............................13 process, software design is the activity, within the software development life cycle, where software requirements are Appendix B – References Used to Write and Justify the analyzed in order to produce a description of the internal Knowledge Area Description ....................................16 structure and organization of the system that will serve as the basis for its construction. More precisely, a software design (the result) must describe the architecture of the 1. INTRODUCTION system, that is, how the system is decomposed and This chapter presents a description of the Software Design organized into components and must describe the interfaces knowledge area for the Guide to the SWEBOK (Stone Man between these components. It must also describe these version). -

Graphic Designer III

City of Portland Job Code: 30000373 CLASS SPECIFICATION Graphic Designer III FLSA Status: Covered Union Representation: Professional and Technical Employees (PTE) GENERAL PURPOSE Under general direction, performs advanced, specialized work in the graphic design and production of printed publications, visual displays, and on-screen presentations; coordinates large, multiple and/or complex graphic design projects including developing time lines, schedules and budgets; provides lead direction to other graphic design staff; and other related duties as assigned. DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS Graphic Designers III perform the more difficult and creatively challenging graphic design assignments. Incumbents analyze bureau needs and plans, schedule and supervise design projects from conceptualization to completion and provide lead work direction and training of other graphic design staff. Graphic Designer III is distinguished from relevant supervisor classes in that incumbents in the latter classes are responsible for assigning, supervising and evaluating professional and technical staff. ESSENTIAL DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES Any one position in this class may not perform all the duties listed below, nor do the listed examples of duties include all similar and related duties that may be assigned to this class. 1. Performs highly skilled graphic design functions and tasks; produces graphic images, including drawings, elevations, isometrics, charts, graphs and digital photographs, for use in paper publishing, Power Point presentations or web-based applications; designs and prepares freehand graphic sketches, perspectives and cartoons to communicate ideas and concepts pictorially. 2. Plans, organizes, assigns and monitors the work of a graphic design work group; develops and implements standards, policies and procedures; monitors the work group budget; prioritizes, plans and schedules projects and processes; checks work and manages work flow. -

Industrialdesign

National Endowment for the Arts I N D U S T R I A L D E S I G N A Competitive Edge for U.S. Manufacturing Success in the Global Economy I N D U S T R I A L D E S I G N A Competitive Edge for U.S. Manufacturing Success in the Global Economy April 2017 National Endowment for the Arts 400 7th Street SW Washington, DC 20506 Telephone: 202-682-5400 arts.gov Produced by Office of Programs and Partnerships, Design Program Jason Schupbach, Director of Design Programs, National Endowment for the Arts Content by Heidi Sheppard, Advisor for Technology Collaborations, National Institute for Standards and Technology, Manufacturing Extension Partnership; Courtney Spearman, Design Specialist, Office of Programs and Partnerships, NEA; and Katryna Carter, Design Consultant, Office of Programs and Partnerships, NEA Other Staff Contributors: Don Ball, Assistant Director - Publications, Office of Public Affairs, NEA; Bonnie Nichols, Operations Research Analyst, Office of Research and Analysis, NEA. Designed by Katryna Carter For their valuable assistance with this report, the NEA Design Program would like to thank the following people: Daniel Martinage, Industrial Designers Society of America; Susan Page Estes and Paul Hatch, DesignHouse; all those who were interviewed; and Laska Hurley, Office of Programs and Partnerships. 202-682-5496 Voice/TTY (a device for individuals who are deaf or hearing-impaired) Individuals who do not use conventional print materials may contact the Arts Endowment’s Office for Accessibility at 202-682-5532 to obtain this publication in an alternate format. This publication is available free of charge in PDF format at arts.gov. -

From Master-Design to Meta-Design

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Presented at our third ds21 conference at the ICA, London, November 17th 2005 http://attainable-utopias.org/tiki/ICA-Conference2005 Please cite Metadesigners Open Network http://metadesigners.org/ From Master-Design to Meta-Design Dr. Ulrike Sturm - Professor at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts I feel there is a need for a new Renaissance in thinking. The old Renaissance brought logic, analysis and judgement – often exercised through argument. The new Renaissance will be powered by design instead of judgement and by creativity instead of logical progression. (Edward de Bono in his weekly message on his homepage, 22nd May 2006) Western thinking is based on the idea of progress. One of its tenets is that mankind is able to shape his future by technical means. At the beginning of the 21st century, however, the belief that rationality will bring about a better living for all has given way to scepticism. Economic activity and technical invention do no longer keep the promise of infinite progress towards betterment. Severe problems on the level of living conditions and ecological threats, however, urge us not to give up the idea of a possible influence on future development. For that reason, one has to look for other means how complex and super-complex systems can be managed, how they can be steered even if an overall control has proven impossible. The Design Synergy 21 project, a part of the British Designing for the 21st Century Initiative, ascribes a leading part to design for future development and regards it as essential, if not existential tool for dealing with complex phenomena. -

Common Tasks Skills Needed in a Graphic Design

Graphic Design Graphic Designer Job Description: Common Tasks Your graphic design job description will likely include the following kinds of tasks: Brainstorming and mocking up design ideas Presenting ideas to clients Meeting with clients and adjusting designs to fit their needs or taste Projecting budgets and schedules Using computer software to execute designs Working with others, such as printers, programmers, developers or other technicians, to complete the final Skills Needed in a Graphic Design Job Artistic Sensibility – In the last few decades, computer software and technology have drastically changed the graphic design industry. Even so, there is no substitute for artistic sensibility. Knowledge about design elements, such as color and composition, is vital for graphic designers. Artistic ability and creativity are essential. Technical Skill – A graphic design job requires the technical skills to use design software programs such as Photoshop or Quark Xpress. You may learn other specific software in graphic design school; however, a general interest in computers and an aptitude for learning new technology will be beneficial. As technology continues to develop, graphic designers hoping for longevity in the field need to be able to adapt. Communication Ability – Sometimes known as visual communication, graphic design requires the ability to effectively present ideas—both verbally and visually. You'll need to be able to sell your ideas to clients and work with them to achieve the end product they want. Organization – Graphic designers need to be organized in order to meet deadlines and stay within a budget. General business skills will come in handy, since many graphic designers work on a freelance or contract basis. -

Beyond User Centered Design Co-Creative Emergent Approaches in the Industrial Design Discipline

BEYOND USER CENTERED DESIGN CO-CREATIVE EMERGENT APPROACHES IN THE INDUSTRIAL DESIGN DISCIPLINE Kevin Shankwiler, IDSA / Claudia B. Rebola Georgia Institute of Technology [email protected] / [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION New understanding of people as users has forced the industrial design discipline to change. Since its origins, industrial design has traditionally attempted to design products for “most” - the target market where new opportunities are identified through market research. In this realm, the emphasis was on fabrication technologies that could produce products affordable for most users. More recently, however, there has been a shift in focus by applying universal design principles with the goal of creating products usable by more people. Universal design principles allowed designers to expand that focus and design for “more.” Currently, most industrial design institution curricula apply user-centered approaches, where universal design is the backbone. However, these methods are still not enough to allow designers to reach "all." In an attempt to accommodate demands of design for all, new methods have been injected into the design process. Linking the two aforementioned approaches advances a new business model in the design discipline. This paper discusses a co-creative emergent approach in the industrial design discipline that allow an understanding of users as individuals and therefore deliver more targeted design solutions for “all”. Novel design methods are discussed including participatory design and parametric modeling linked with digital fabrication. The authors discuss the links and relationships between the methods and how they complement each other throughout the course of the design process. The significance of this paper is to advance a new model of delivering better-suited products and services to the user needs within the discipline. -

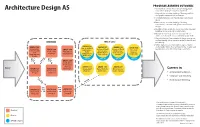

Architecture Design AS 1

PROGRAM LEARNING OUTCOMES Architecture Design AS 1. Communicate architectural concepts using graphic conventions and representational methods. 2. Demonstrate an understanding of drawing methods and graphic compositional techniques. 3. Construct physical models of architectural elements and spaces. 4. Demonstrate an understanding of building components, structures and systems in relation to design. 5. Identify notable architects, design concepts, canonical buildings and precedents in architecture. 6. Identify the historical and contemporary role of architects in the profession and related design fields. 7. Describe the role of environmental design, energy use and sustainable design practices in the profession and REQUIRED TAKE 3 units in buildings. 8. Utilize digital means of production, representation ARCHI 120 ARCHI 156 and/or digital fabrication methods for the creation and History of World ARCHI 157 ARCHI 158 ARCHI 160 Introduction History of World History of World manipulation of architectural images and forms. ARCHI 130 CONST 144 Architecture: History of to Architecture Architecture: Architecture: Architectural Materials of Early and Middle Ages to 18th Century to American Graphics I Construction Civilizations to Environmental 18th Century Present Architecture Design Middle Ages pre pre DVC III DVC III DVC III DVC III req co req req ARCHI 244 Architectural Practice and Working ARCHI 110 ARCHI 136 ARCHI 207 Entry ARCHI 121 ARCHI 131 Drawings I Design-Build Digital Tools for Environmental Careers in Architectural Architectural Workshop Architecture Control Systems Design I Graphics II • Architectural technician • Computer aided drafting pre req • Architectural rendering co req pre pre ARCHI 135 req ARCHI 220 req ARCHI 221 Digital Tools Architectural Architectural for Design Design II Design III You need to see a Counselor for specific recommendations about courses that will best meet your educational goals. -

Software Design and Solutions

UNDERGRADUATE CERTIFICATE | TECH SOFTWARE DESIGN AND SOLUTIONS ABOUT THIS PROGRAM QUICK FACTS IS THIS PROGRAM FOR YOU? Are you interested in how software is designed and operated? Or how to test and design software for all types of devices? In this certificate program, students 42 14 1+4 will be exposed to the complete software development life cycle and have the CREDIT HOURS COURSES YEAR MONTHS minimum credit hours minimum length for graduation1 opportunity to contribute to it. required for graduation A PROGRAM TO FUEL YOUR FUTURE Engage in course material exploring topics like data structures and algorithms, ANCHORED IN TECH CORE and software engineering to help prepare you to work on various types Prepare to be immersed in coursework designed to help you build of software system. Learn the skills needed to program software using interdisciplinary skills you’ll need for today’s Internet of Things (IoT) industry recognized programming languages like Python. Learning these two economy. Project work and activities allow you to develop relevant skills in: programming languages will help prepare you to learn new languages during the • Digital Devices • Coding • Operating Systems course of your career. WORK WITH IOT TECHNOLOGIES & SYSTEMS CAREER OPPORTUNITIES Immerse yourself in the Internet of Things (IoT) world and obtain hands-on Graduates of DeVry’s Software Design and Solutions certificate program may experience with IoT, cloud, software and security technologies and systems. consider, but are not limited to, entry level opportunities in positions, such as: CERTIFICATION EXAM ALIGNED CURRICULUM • Software Applications Developer Experience elements of our technology curriculum focused on real-world • Mobile App Developer industry standards and prepare for certification opportunities that help validate your knowledge and skills. -

Seven Legal Issues Unique to Design-Build

Article Seven Legal Issues Unique to Design-Build By Mark C. Friedlander June 5, 2015 As design-build as a project delivery method continues to grow in popularity, practitioners have begun to question exactly it is different from traditional design-bid-build projects. In general terms, contractors are aware that design- build ordinarily shortens project delivery time and leaves the design-builder responsible for the entire project. However, there is a need for a greater understanding of precisely which legal and business issues have different implications for design-build projects as opposed to traditional design-bid-build projects. The legal issues arising uniquely out of the design-build method of project delivery are not overly complex. Although all complex construction projects involve important legal issues, there are not a great number of additional legal issues that arise in design-build projects as opposed to the traditional design-bid-build mode. After having been involved in a large number of design-build projects in both the public and private sectors, it seems to me that the legal issues that are unique to design-build projects can be broken down into the following seven categories: • The relationships and loyalties among the parties. • The design professional’s standard of care. • Performance warranties. • Entitlement to Change orders. • Licensing problems. • Insurance/Bonding problems. • Conflicts with competitive bidding laws. The following is a brief summary of how these issues differ from those in traditional construction projects. The Relationships Among The Parties The most obvious change distinguishing design-build from traditional design-bid-build projects is that the design professional is not the owner’s consultant, and is instead the contractor’s teammate.