When School Is Not in Session: How Student Drug Testing Can Transform Parenting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC World Service : Overseas Broadcasting, 1932-2018 Pdf Free Download

BBC WORLD SERVICE : OVERSEAS BROADCASTING, 1932-2018 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gordon Johnston | 338 pages | 26 Nov 2019 | Palgrave MacMillan | 9780230355606 | English | Basingstoke, United Kingdom BBC World Service : Overseas Broadcasting, 1932-2018 PDF Book Radio Times. A few months ago this was valuable information for those travelling abroad who wanted their fix of BBC radio coverage. Within a decade, the service began adding languages and regions, and currently broadcasts to people around the world in 27 languages, with a broad range of programs including news, music, comedy and documentaries. Ships within weeks Not available in stores. The Travel Show , Our World. Secession [Hardcover] Hardback. The Doha Debates. The easiest way to work around such restrictions is by using a VPN. Featuring psalm settings for each Sunday and all the major feast days, this essential musical resource is the first publication to feature the psalm texts that are used in the new Canadian lectionary. Huw Edwards. As radio streams don't hog bandwidth to the extent that streaming TV does, most good VPN services are perfectly adequate for virtually moving back to the UK to listen to a restricted programme. Can I view this online? Retrieved 21 November BBC Television. BBC portal. Editor: Sarah Smith. Retrieved 9 February The Bottom Line. The Random House Group. Advanced search Search history. We have recently updated our Privacy Policy. Need Help? The phrase "but for now" means among other things "making do," as if we had to settle for the bare minimum. Presenters who have normal shows and also Relief present have their relief shows in bold. -

Negotiating Bankruptcy Legislation Through the News Media Melissa B

University of North Carolina School of Law Carolina Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2004 Negotiating Bankruptcy Legislation Through the News Media Melissa B. Jacoby University of North Carolina School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Publication: Houston Law Review This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE NEGOTIATING BANKRUPTCY LEGISLATION THROUGH THE NEWS MEDIA Melissa B. Jacoby* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................1092 II. LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENT AND THE PROMINENT BANKRUPTCY STORY ...........................................................1095 A. 105th Congress (1997–1998) .......................................1098 B. 106th Congress (1999–2000) .......................................1102 C. 107th Congress (2001–2002) .......................................1104 D. 108th Congress (2003–2004) .......................................1105 III. THE RELEVANCE OF MEDIA TREATMENT TO DEVELOPMENTS IN BANKRUPTCY LEGISLATION .................1107 IV. THREE PROMINENT EMERGING FRAMES OF BANKRUPTCY .................................................................1117 -

View Or Download the Full Journal As A

Journalism Education The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education Volume six, number one, Spring 2017 Page 2 Journalism Education Volume 6 number 1 Journalism Education Journalism Education is the journal of the Association for Journalism Education a body representing educators in HE in the UK and Ireland. The aim of the journal is to promote and develop analysis and understanding of journalism education and of journalism, particu- larly when that is related to journalism education. Editors Mick Temple, Staffordshire University Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University Deirdre O’Neill, Huddersfield University Stuart Allan, Cardiff University Reviews editor: Tor Clark, de Montfort University You can contact the editors at [email protected] Editorial Board Chris Atton, Napier University Olga Guedes Bailey, Nottingham Trent University David Baines, Newcastle University Guy Berger, UNICEF Jane Chapman, University of Lincoln Martin Conboy, Sheffield University Ros Coward, Roehampton University Stephen Cushion, Cardiff University Susie Eisenhuth, University of Technology, Sydney Ivor Gaber, Bedfordshire University Roy Greenslade, City University Mark Hanna, Sheffield University Michael Higgins, Strathclyde University John Horgan, Irish press ombudsman (retired) Sammye Johnson, Trinity University, San Antonio, USA Richard Keeble, University of Lincoln Mohammed el-Nawawy, Queens University of Charlotte An Duc Nguyen, Bournemouth University Sarah Niblock, Brunel University Bill Reynolds, Ryerson University, Canada Ian Richards, -

ENCLOSED: the Best Deal We Can Offer. the BEST DEAL

ENCLOSED: The best deal we can offer. THE BEST DEAL CHOOSE YOUR SUBSCRIPTION: That’s only 57¢ a day! PAYMENT INFORMATION 7 Days a Week–$3.99 per week (You pay $31.92 every 8 weeks) My check is enclosed for my first 8 weeks. Sunday-Only–$1.99 per week (You pay $15.92 every 8 weeks) (payable to Newsday.) REPLY BY: 1/31/15 OFFER CODE <CODE> Please charge my credit card: AmEx Discover MasterCard Visa Card No. Exp. Date (MM/YY) <Firstname> <Lastname> <Address_Line_1> Cardholder’s Signature <Address_Line_2> <City>, <ST> <ZIP+4> Phone Number <Barcode> Email Address (for information about your subscription) DETACH AT PERFORATION. COMPLETE TOP PORTION AND MAIL IN THE POSTAGE-PAID ENVELOPE PROVIDED. 1214-A3 SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND SAVE UP TO 70% As a former Newsday subscriber, you have been selected to receive the absolute best pricing we can offer at this time. Choose 7 Days, or Sunday-Only with BIG SAVINGS off the regular rate—up to 70% for 26 weeks. GET ALL THIS FOR OUR LOWEST PRICE: •News. The only newspaper you need for Long Island and national news •Sports. From local to global, amateur to pro, if it’s a sport you love, you’ll find it in Newsday FOR IMMEDIATE ACTION, CALL •Long Island Life. Things to do on Long Island and in NYC all week long! 1-800-NEWSDAY •Money-saving coupons worth hundreds of dollars at stores you love! (MENTION OFFER CODE <CODE>) OR CLICK: SUB.NEWSDAY.COM/<CODE> PLUS, get UNLIMITED DIGITAL ACCESS to Newsday.com and Newsday Apps! This 26-week introductory offer is valid for new Nassau and Suffolk subscribers who have not received Newsday home delivery in the past 60 days. -

Media Kit Mission Statement

MEDIA KIT MISSION STATEMENT..................................................... 2 WHO WE ARE Market ........................................................................ 3 Readership/Circulation .............................................. 5 Audience Profile/Composition .................................. 6 WHAT WE OFFER PRINT Newspaper ........................................................... 7 Themed Sections ................................................. 7 Preprints ............................................................... 8 Direct Marketing ................................................... 8 Niche Publications ................................................ 9 Classified ............................................................ 11 DIGITAL Newsday.com & Newsday App .......................... 12 Newsday Downloadable Paper .......................... 12 Feed Me .............................................................. 12 Newsday App for Apple TV® & Roku TV® ........... 13 Newsletters & Alerts ........................................... 13 AdMail/Email ....................................................... 13 Newsday Connect .............................................. 14 Data and Analytics.............................................. 14 Programmatic Direct .......................................... 14 BRAND360 CUSTOM CONTENT STUDIO ............. 15 EVENTS & EXPERIENTIAL MARKETING ................ 16 NEWSDAY MEDIA GROUP Newsday & amNewYork .......................................... 17 PRINT & SPECIAL SECTIONS -

Educator Sexual Misconduct: a Synthesis of Existing Literature

POLICY AND PROGRAM STUDIES SERVICE Educator Sexual Misconduct: A Synthesis of Existing Literature 2004 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OFFICE OF THE UNDER SECRETARY DOC # 2004-09 Educator Sexual Misconduct: A Synthesis of Existing Literature Prepared for the U.S. Department of Education Office of the Under Secretary Policy and Program Studies Service By Charol Shakeshaft Hofstra University and Interactive, Inc. Huntington, N.Y. 2 This report was prepared for the U.S. Department of Education under Purchase Order ED-02-PO-3281. The views expressed herein are those of the authors. No official endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education is intended or should be inferred. U.S. Department of Education Rod Paige Secretary June 2004 This report is in the public domain. Authorization to reproduce it in whole or in part is granted. While permission to reprint this publication is not necessary, the citation should be: U.S. Department of Education, Office of the Under Secretary, Educator Sexual Misconduct: A Synthesis of Existing Literature, Washington, D.C., 2004. CONTENTS 1.0 Purpose and Methods of Synthesis 1 1.1 Definitions 1.2 Scope of synthesis search 1.3 Methods of synthesis 2.0 Description of Existing Research, Literature, or Other Verifiable Sources 4 2.1 Categories of discourse 2.2 Systematic studies 2.3 Practice-based accounts with first or third person descriptions 2.4 Newspaper and other media sources 2.5 General child sexual abuse data sets and instruments 2.6 Availability of research 3.0 Prevalence of Educator Sexual Misconduct 16 -

World Service Listings for 2 – 8 January 2021 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 02 JANUARY 2021 Arabic’S Ahmed Rouaba, Who’S from Algeria, Explains Why This with Their Heritage

World Service Listings for 2 – 8 January 2021 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 02 JANUARY 2021 Arabic’s Ahmed Rouaba, who’s from Algeria, explains why this with their heritage. cannon still means so much today. SAT 00:00 BBC News (w172x5p7cqg64l4) To comment on these stories and others we are joined on the The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. Remedies for the morning after programme by Emma Bullimore, a British journalist and Before coronavirus concerns in many countries, this was the broadcaster specialising in the arts, television and entertainment time of year for parties. But what’s the advice for the morning and Justin Quirk, a British writer, journalist and culture critic. SAT 00:06 BBC Correspondents' Look Ahead (w3ct1cyx) after, if you partied a little too hard? We consult Oleg Boldyrev BBC correspondents' look ahead of BBC Russian, Suping of BBC Chinese, Brazilian Fernando (Photo : Indian health workers prepare for mass vaccination Duarte and Sharon Machira of BBC Nairobi for their local drive; Credit: EPA/RAJAT GUPTA) There were times in 2020 when the world felt like an out of hangover cures. control carousel and we could all have been forgiven for just wanting to get off and to wait for normality to return. Image: Congolese house at the shoreline of Congo river SAT 07:00 BBC News (w172x5p7cqg6zt1) Credit: guenterguni/Getty Images The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. But will 2021 be any less dramatic? Joe Biden will be inaugurated in January but will Donald Trump have left the White House -

Using Single-Platform Social Media Newsdays in Television Journalism Education: a Heutogogical Approach Katherine Blair, Leeds Trinity University

Page 96 Journalism Education Volume 8 number 2 Using single-platform social media newsdays in television journalism education: a heutogogical approach Katherine Blair, Leeds Trinity University Keywords: Heutagogy, practice-based learning (PBL), university learning and teaching, higher education, student-negotiated assessment, journalism, broadcast journalism, education, television news, social media Abstract Traditionally, journalism education has been a mix of aca- demic and practical classes. It often uses close-to-indus- try simulations in the form of student news rooms and newsdays which replicate industry practices. For televi- sion journalism, this has included newsdays which begin with a 9:00 news conference, and end with the live TV studio news programme. In order to maintain currency, elements such as social media posts have been added alongside the traditional television packaging. However, these aspects have often taken a backseat to the main focus of the studio news programme. In order to address this, I experimented with single-platform social media newsdays; focusing on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. According to a Pew Research report in 2018, about four-in-ten Americans (43%) get news on Facebook. The next most commonly used site for news is YouTube, with 21% getting news there, followed by Twitter at 12%. Smaller portions of Americans (8% or fewer) get news from other social networks like Instagram, Linked- In or Snapchat. Further, a Reuters Institute study found a third of young people say social media is their main source for news, more than online news sites, and TV and printed newspapers. Clearly, social is an important platform for delivering news, yet it follows different, and as yet undefined rules of production and delivery. -

Kalte Heimat

FERNSEHEN 14 Tage TV-Programm .11. bis 11.. Deutsch-österreichischer Thriller „Der Pass“ ab 1. Dezember als Free-TV-Premiere im ZDF Kalte Heimat Serbien – Der vergessene Krieg Castle Rock & Mr. Mercedes Feature über den Balkankrieg und seine Neues von Stephen King auf Blu ray und Folgen im Kulturradio als Stream, Teil 2 TV_2519_01_Titel.indd 1 14.11.19 17:16 Fernsehen 28.11. – 11.12. Alles eine Wumpe KOMMENTAR VOM TELEVISOR Auf Netflix steht seit dem 1. Novem- ber die neueste deutsche Eigenprodukti- on zum Streamen bereit, eine Neuinter- pretation des Schulbuchklassikers „Die Welle“. Auch wenn der kurze Roman von dem Amerikaner Morton Rhue stammt, ist er in Deutschland doch ungleich be- kannter als in den USA und gehört seit dem Erscheinen 1981 zum Schulkanon. Nun ist „Die Welle“ zwar nicht besonders Bei dieser Kälte muss man einfach einen Flunsch ziehen: Julia Jentsch (Foto, Mi.) gut geschrieben, aber thematisch schon interessant, schildert das Buch doch ein soziologisches Experiment, dass der Leh- Halb und halb rer Ron Jones durchgeführt hat. Es geht um die Verführbarkeit von Menschen Die deutsch-österreichische Sky Deutschland-Eigenproduktion zum Faschismus. Die Frage, ob das Buch Der Pass ist jetzt im ZDF – und erstmals frei – zu sehen das Experiment realistisch schildert, ist eher unerheblich; deshalb kann man auch Hoch droben in den Bergen wird eine in den Tod“, überzeugt jedoch mit einer stilistische Schwächen eher entschuldi- Leiche aufgefunden, die zu allem Über- eigenen Erzählweise. So wird die Identität gen. Aber Faschismus hat hier keine fluss exakt auf der deutsch-österreichi- des Killers bereits in Folge drei offenbart. -

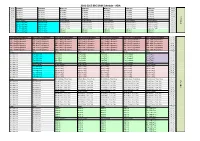

2016-2017 BBC DRM Schedule

2016-2017 BBC DRM Schedule - ASIA 08:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 08:00 08:06 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 08:06 08:10 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 08:10 08:15 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 08:15 08:20 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 08:20 08:25 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 08:25 08:29 News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update 08:29 08:32 The Food Chain Outlook (wke) Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 08:32 08:35 The Food Chain Outlook (wke) Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 08:35 DRM for Asia 08:41 The Food Chain Outlook (wke) Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 08:41 08:45 The Food Chain Outlook (wke) Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 08:45 08:50 The Food Chain Outlook (wke) Witness 1 Witness 2 Witness 3 Witness 4 Witness 5 08:50 08:55 The Food Chain Outlook (wke) Witness 1 Witness 2 Witness 3 Witness 4 Witness 5 08:55 BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes 14:29 BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes 14:32 BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes BBC Hindi Programmes -

Your Guide to the BBC World Service Schedule from Sunday 28 March 2021

UK Your guide to the BBC World Service schedule From Sunday 28 March 2021 https://wspartners.bbc.com/ BST GMT Saturday Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday GMT 01:00 00:00 News Bulletin News Bulletin News Bulletin News Bulletin News Bulletin News Bulletin News Bulletin 00:00 01:06 00:06 Business Matters The Science Hour World Business Report Business Matters Business Matters Business Matters Business Matters 00:06 01:30 00:30 News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update 00:30 01:32 00:32 Business Matters The Science Hour Discovery (Rpt) Business Matters Business Matters Business Matters Business Matters 00:32 02:00 01:00 The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom 01:00 02:30 01:30 News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update 01:30 02:32 01:32 Stumped When Katty Met Carlos The Climate Question The Documentary (Tue) The Compass Assignment World Football 01:32 03:00 02:00 News Bulletin News Bulletin News Bulletin News Bulletin News Bulletin News Bulletin News Bulletin 02:00 03:06 02:06 The Fifth Floor The Documentary (Weekend) ^ Weekend Feature Outlook Outlook Outlook Outlook 02:06 03:30 02:30 News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update News Update 02:30 03:32 02:32 The Fifth Floor The Documentary (Weekend) ^ The Story Outlook Outlook Outlook Outlook 02:32 03:50 02:50 Witness History Over To You Witness History Witness History Witness History Witness History 02:50 04:00 03:00 -

Nassau County High School Athletics Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony

Nassau County High SchoolHigh School Athletics HallAthletics of Fame InductionHall of Ceremony Fame Induction Ceremony September 27, 2017 SeptemberCrest Hollow 30, 2015 CrestCountry Hollow Club Country Club NASSAU COUNTY HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETICS HALL OF FAME WELCOME The Nassau County High School Athletics Hall of Fame is organized as a means of recognizing, preserving and promoting the heritage of interscholastic sports in Nassau County. The Nassau County High School Athletics Hall of Fame honors the contributions and accomplishments of individuals who are worthy of county- wide recognition. Nominees must exemplify the high standards of sportsmanship, ethical conduct and moral character. The categories of nomination include: Administrator, Official, Contributor, Athlete and co a c h. All candidates for the Nassau County High School Athletics Hall of Fame must be at least 35 years of age prior to December 1st of the applicable year in order to be considered for induction. Nominees for the Nassau County High School Athletics Hall of Fame will go through a two-step process before being selected for induction. The ten (10) member Screening Committee will determine which candidates are worthy of consideration. The five (5) anonymous members of the Selection Committee vote independently to determine the candidates who will be inducted into the Hall of Fame. Applications can be found on the Section VIII website at www.nassauboces.org/athletics. All nominations for the 2018 Hall of Fame are due on February 1, 2018. PROGRAM Introduction of the Class of 2017 Master of Ceremonies – Carl Reuter Honor America Star Spangled Banner Tommy Barone Opening Remarks Dominick Vulpis Section VIII Assistant Executive Director Invocation Father Francis Pizzarelli, S.M.M.