Low-Cost Carriers and Secondary Airports Three Experiences from Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulamento (Ue) N

11.2.2012 PT Jornal Oficial da União Europeia L 39/1 II (Atos não legislativos) REGULAMENTOS o REGULAMENTO (UE) N. 100/2012 DA COMISSÃO de 3 de fevereiro de 2012 o que altera o Regulamento (CE) n. 748/2009, relativo à lista de operadores de aeronaves que realizaram uma das atividades de aviação enumeradas no anexo I da Diretiva 2003/87/CE em ou após 1 de janeiro de 2006, inclusive, com indicação do Estado-Membro responsável em relação a cada operador de aeronave, tendo igualmente em conta a expansão do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União aos países EEE-EFTA (Texto relevante para efeitos do EEE) A COMISSÃO EUROPEIA, 2003/87/CE e é independente da inclusão na lista de operadores de aeronaves estabelecida pela Comissão por o o força do artigo 18. -A, n. 3, da diretiva. Tendo em conta o Tratado sobre o Funcionamento da União Europeia, (5) A Diretiva 2008/101/CE foi incorporada no Acordo so bre o Espaço Económico Europeu pela Decisão o Tendo em conta a Diretiva 2003/87/CE do Parlamento Europeu n. 6/2011 do Comité Misto do EEE, de 1 de abril de e do Conselho, de 13 de Outubro de 2003, relativa à criação de 2011, que altera o anexo XX (Ambiente) do Acordo um regime de comércio de licenças de emissão de gases com EEE ( 4). efeito de estufa na Comunidade e que altera a Diretiva 96/61/CE o o do Conselho ( 1), nomeadamente o artigo 18. -A, n. 3, alínea a), (6) A extensão das disposições do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União, no setor da aviação, aos Considerando o seguinte: países EEE-EFTA implica que os critérios fixados nos o o termos do artigo 18. -

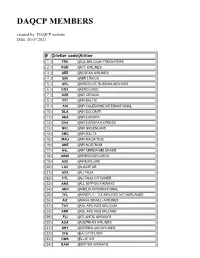

DAQCP MEMBERS Created By: DAQCP Website Date: 20.07.2021

DAQCP MEMBERS created by: DAQCP website Date: 20.07.2021 # 3-letter code Airline 1 FRH ACE BELGIUM FREIGHTERS 2 RUN ACT AIRLINES 3 AEE AEGEAN AIRLINES 4 EIN AER LINGUS 5 AFL AEROFLOT RUSSIAN AIRLINES 6 BOX AEROLOGIC 7 KZR AIR ASTANA 8 BTI AIR BALTIC 9 ACI AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 10 DLA AIR DOLOMITI 11 AEA AIR EUROPA 12 OVA AIR EUROPA EXPRESS 13 GRL AIR GREENLAND 14 AMC AIR MALTA 15 MAU AIR MAURITIUS 16 ANE AIR NOSTRUM 17 ASL AIR SERBIA BELGRADE 18 ABW AIRBRIDGECARGO 19 AXE AIREXPLORE 20 LAV ALBASTAR 21 AZA ALITALIA 22 CYL ALITALIA CITYLINER 23 ANA ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS 24 AEH AMELIA INTERNATIONAL 25 TFL ARKEFLY - TUI AIRLINES NETHERLANDS 26 AIZ ARKIA ISRAELI AIRLINES 27 TAY ASL AIRLINES BELGIUM 28 ABR ASL AIRLINES IRELAND 29 FLI ATLANTIC AIRWAYS 30 AUA AUSTRIAN AIRLINES 31 AHY AZERBAIJAN AIRLINES 32 CFE BA CITYFLYER 33 BMS BLUE AIR 34 BAW BRITISH AIRWAYS 35 BEL BRUSSELS AIRLINES 36 GNE BUSINESS AVIATION SERVICES GUERNSEY LTD 37 CLU CARGOLOGICAIR 38 CLX CARGOLUX AIRLINES INTERNATIONAL S.A 39 ICV CARGOLUX ITALIA 40 CEB CEBU PACIFIC 41 BCY CITYJET 42 CFG CONDOR FLUGDIENST GMBH 43 CTN CROATIA AIRLINES 44 CSA CZECH AIRLINES 45 DLH DEUTSCHE LUFTHANSA 46 DHK DHL AIR LTD. 47 EZE EASTERN AIRWAYS 48 EJU EASYJET EUROPE 49 EZS EASYJET SWITZERLAND 50 EZY EASYJET UK 51 EDW EDELWEISS AIR 52 ELY EL AL 53 UAE EMIRATES 54 ETH ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 55 ETD ETIHAD AIRWAYS 56 MMZ EUROATLANTIC 57 BCS EUROPEAN AIR TRANSPORT 58 EWG EUROWINGS 59 OCN EUROWINGS DISCOVER 60 EWE EUROWINGS EUROPE 61 EVE EVELOP AIRLINES 62 FIN FINNAIR 63 FHY FREEBIRD AIRLINES 64 GJT GETJET AIRLINES 65 GFA GULF AIR 66 OAW HELVETIC AIRWAYS 67 HFY HI FLY 68 HBN HIBERNIAN AIRLINES 69 HOP HOP! 70 IBE IBERIA 71 ICE ICELANDAIR 72 ISR ISRAIR AIRLINES 73 JAL JAPAN AIRLINES CO. -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

Not for Distribution in the United States

NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES Alitalia – Società Aerea Italiana S.p.A. (incorporated with limited liability under the laws of the Republic of Italy) €375,000,000 5.250 per cent. Notes due 30 July 2020 The issue price of the €375,000,000 5.250 per cent. Notes due 30 July 2020 (the “Notes”) of Alitalia – Società Aerea Italiana S.p.A. (the “Issuer” or “Alitalia”) is 100 per cent. of their principal amount. Unless previously redeemed or cancelled, the Notes will be redeemed at their principal amount on 30 July 2020. The Notes are subject to redemption, in whole but not in part, at their principal amount, plus interest, if any, to the date fixed for redemption in the event of certain changes affecting taxation in the Republic of Italy and at the option of the Issuer at any time at an amount calculated on a “make-whole” basis. In addition, the holder of a Note may, by the exercise of the relevant option, require the Issuer to redeem or, at the Issuer’s option, purchase such Note at 100 per cent. of its principal amount together with accrued and unpaid interest (if any) to (but excluding) the Put Date upon the occurrence of a Change of Control (each as defined below). See “Terms and Conditions of the Notes — Redemption and Purchase”. The Notes will bear interest from (and including) 30 July 2015 (the “Issue Date”) at the rate of 5.250 per cent. per annum. Interest on the Notes will be payable annually in arrear on 30 July in each year. -

Elenco Codici IATA Delle Compagnie Aeree

Elenco codici IATA delle compagnie aeree. OGNI COMPAGNIA AEREA HA UN CODICE IATA Un elenco dei codici ATA delle compagnie aeree è uno strumento fondamentale, per chi lavora in agenzia viaggi e nel settore del turismo in generale. Il codice IATA delle compagnie aeree, costituito da due lettere, indica un determinato vettore aereo. Ad esempio, è utilizzato nelle prime due lettere del codice di un volo: – AZ 502, AZ indica la compagnia aerea Alitalia. – FR 4844, FR indica la compagnia aerea Ryanair -AF 567, AF, indica la compagnia aerea Air France Il codice IATA delle compagnie aeree è utilizzato per scopi commerciali, nell’ambito di una prenotazione, orari (ad esempio nel tabellone partenza e arrivi in aeroporto) , biglietti , tariffe , lettere di trasporto aereo e bagagli Di seguito, per una visione di insieme, una lista in ordine alfabetico dei codici di molte compagnie aeree di tutto il mondo. Per una ricerca più rapida e precisa, potete cliccare il tasto Ctrl ed f contemporaneamente. Se non doveste trovare un codice IATA di una compagnia aerea in questa lista, ecco la pagina del sito dell’organizzazione Di seguito le sigle iata degli aeroporti di tutto il mondo ELENCO CODICI IATA COMPAGNIE AEREE: 0A – Amber Air (Lituania) 0B – Blue Air (Romania) 0J – Jetclub (Svizzera) 1A – Amadeus Global Travel Distribution (Spagna) 1B – Abacus International (Singapore) 1C – Electronic Data Systems (Svizzera) 1D – Radixx Solutions International (USA) 1E – Travelsky Technology (Cina) 1F – INFINI Travel Information (Giappone) G – Galileo International -

Key Information for the Registered Party - COURTESY TRANSLATION1 (In Force Since 7Th April 2020)

Iscrizione albo Covip con numero d'ordine 167 Section I - Key Information for the Registered Party - COURTESY TRANSLATION1 (in force since 7th April 2020) This document aims to present the main characteristics of Fondaereo and to facilitate the comparison between Fondaereo and the other supplementary pension schemes. A. FUND PRESENTATION The Supplementary Pension Fund for the Air Transport Sector, Pilots and Flight Assistants (hereinafter referred to as the Fund) is a pension fund negotiable on the basis of the collective bargaining agreements indicated in the Annex to this Key Information for the subscriber, which forms an integral part thereof. Fondaereo aims to provide supplementary pension benefits to the compulsory social security system, in accordance with Legislative Decree No. 252 of 5 December 2005, and operates under a defined-contribution system: the amount of the retirement benefit is determined on the basis of the contribution paid and the management returns. The management of the resources is carried out in the exclusive interest of the beneficiaries and in accordance with the investment indications provided by them, choosing between the proposals presented. Workers belonging to the categories of pilots and flight attendants referred to in Article 1 of Law 480/88, employees of the companies listed in the Annex to this Key Information for the beneficiary, including the main information and the conditions of participation, may subscribe to Fondaereo. Workers belonging to the categories of flight crew, as indicated in Article 1 of Law 480/88, who work for the companies referred to in the same Article, may be eligible for the benefits of the Fund. -

00194 Roma Commission Européenne/Europese Commissie, 1049 Bruxelles/Brussel, BELGIQUE/BELGIË - Tel

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 29.12.2020 C(2020) 9659 final In the published version of this decision, some PUBLIC VERSION information has been omitted, pursuant to articles 30 and 31 of Council Regulation (EU) This document is made available for 2015/1589 of 13 July 2015 laying down information purposes only. detailed rules for the application of Article 108 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, concerning non-disclosure of information covered by professional secrecy. The omissions are shown thus […] Subject: State Aid SA.59188 (2020/NN) – Italy – COVID-19 aid to Alitalia Excellency, 1. PROCEDURE (1) By electronic notification of 25 December 20201, the Italian Republic notified aid to Alitalia – Società Aerea Italiana S.p.A in Extraordinary Administration (“Alitalia”) in the form of a EUR 73.02 million grant (“the Measure”). This Measure is granted (i) under the fund established by Article 79 of Decree-Law No 18 of 17 March 2020 granting compensation to airlines affected by the COVID-19 outbreak (“the Fund”), in accordance with Article 108(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European 1 The notification followed preliminary exchanges between the Italian authorities and the Commission services, which started on 23 October 2020 with the submission of a pre-notification from the Italian authorities. The Commission’s services sent a request for information on 12 November 2020, to which the Italian authorities replied on 27 November 2020. On 11 December 2020, the Commission services sent an additional request for information to the Italian authorities that replied on 14 December 2020. -

Rappo Report and Social Balance

Printed in June 2016 June in Printed ENAC Report and Social Balance PRESIDENZA E DIREZIONE GENERALE Gemmagraf 2007 Srl 2007 Gemmagraf Viale Castro Pretorio, 118 - 00185 Roma Graphic design, translation and printing: and translation design, Graphic 2015 AuthorityItalian CivilAviation Tel. +39 06 44596-1 for their collaboration their for PEC: [email protected] We would like to thank all ENAC’s Depts. ENAC’s all thank to like would We www.enac.gov.it Acknowledgements Directorate General - President Staff President - General Directorate Silvia Mone Silvia PRESIDENTE Report and Social Balance Social and Report Head of Media Relations Unit Relations Media of Head Vito Riggio Loredana Rosati Loredana Institutional Communication Unit Communication Institutional CONSIGLIO DI AMMINISTRAZIONE ENAC Italian Civil Aviation Authority Aviation Civil Italian Francesca Miceli Francesca In attesa ricostituzione Organo 2015 Supervisor of Trasparency of Supervisor Director of Human Resources Dept. Resources Human of Director COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI DEI CONTI Maria Elena Taormina Elena Maria Giampaolo Bologna (Presidente) With the collaboration of collaboration the With Carmelo Caruso Head of Institutional Communication Unit Communication Institutional of Head Sergio Zanetti Maria Pastore Pastore Maria Editorial Coordination Editorial DIRETTORE GENERALE Alessio Quaranta Coordinamento editoriale Alessio Quaranta Quaranta Alessio Maria Pastore Responsabile Funzione Organizzativa DIRECTOR GENERAL DIRECTOR Comunicazione Istituzionale Sergio Zanetti Zanetti -

Economics of the Airline Industry

Master's Degree programme in INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004) Final Thesis Economics of the Airline Industry The Alitalia bankruptcy: a review Supervisor Ch. Prof. Chiara Saccon Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Marco Vedovato Graduand Andrea Rizzetto Matriculation Number 865717 Academic Year 2016 / 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Prof. Chiara Saccon of the Management Department at Ca’ Foscari - University of Venice. She consistently allowed this paper to be my own work, but steered me in the right direction whenever she thought I needed it. I would also like to thank the air transport industry expert Captain Fabio Cassan for the professional and continued support he gave me and for the preface he wrote to sign this dissertation. Finally, last but not least, I would like to thank my family, my girlfriend and my friends, without whose support it would not have been possible this one and a half years master’s degree experience. Acknowledgements Index Preface by Fabio Cassan I Introduction IV CHAPTER ONE — Air Transport industry overview 1 1. A long story short 2 2. A fast-growing industry 4 3. International Institutional and Regulatory Environment 7 3.1. The Chicago Convention 8 3.1.1. The Freedoms of the Air 9 3.2. Airline industry privatisation 10 3.2.1. United States vs. European Union: different perspective same goal 11 3.2.2. The Effects 12 4. Aviation Industry and the World Economy 15 CHAPTER TWO — Airline Economics, Costs and Revenues 18 1. The basic airline profit equation 19 2. -

IMPRESE TITOLARI DI LICENZA DI TRASPORTO AEREO Triletterale Tipologia Impresa Sede Legale CAP Città Pec Telefono Fax ICAO V Aelia S.R.L

Ente Nazionale per l'Aviazione Civile A cura della Direzione Sviluppo Trasporto Aereo e Licenze IMPRESE TITOLARI DI LICENZA DI TRASPORTO AEREO Triletterale Tipologia Impresa Sede legale CAP Città Pec Telefono Fax ICAO V AElia S.r.l. Via Santo Stefano n. 10 40125 Bologna (BO) [email protected] 051 232323 051 232323 V AAU Aeropa S.r.l. Licenza sospesa da 01/10/2019 Via Antonio Ciamarra n. 259 00173 Roma (RM) [email protected] 06 70340559 06 79340382 E CPV Air Corporate S.r.l. Via Monte Baldo n. 10 37069 Villafraca di Verona (VR) [email protected] 045 8600910 045 8618105 V* DLA Air Dolomiti S.p.A. Linee Aeree Regionali Europee Via Paolo Bembo n. 70 37062 Dossobuono di Villafranca (VR) [email protected] 045 8605211 045 8605229 Centro Direzionale Aeroporto Costa V* ISS AIR ITALY S.p.A. 07026 Olbia (SS) [email protected] 0789 52600 0789 52972 Smeralda E RCX Air Service Center S.r.l. Frazione Fabbrica n. 31/A 27040 Arena Po (PV) [email protected] 0385 272117 0385 272357 E Airgreen S.r.l. Via Fiano n. 175 10070 Robassomero (TO) [email protected] 011 9235971 011 9235885 E Airstar Aviation S.r.l. Via per Castelletto Cervo n. 316 13836 Cossato (BI) [email protected] 015 9840196 015 4691674 V AFQ Alba Servizi Aerotrasporti S.p.A. Via Paleocapa n. 3 20121 Milano (MI) [email protected] 02 21026181 02 21025301 E LID Alidaunia S.r.l. Strada Statale 673 km. 19,00 s.n.c. 71100 Foggia (FG) [email protected] 0881 617961 0881 619660 V PAJ Aliparma S.r.l. -

List of EU Air Carriers Holding an Active Operating Licence

Active Licenses Operating licences granted Member State: Austria Decision Name of air carrier Address of air carrier Permitted to carry Category (1) effective since ABC Bedarfsflug GmbH 6020 Innsbruck - Fürstenweg 176, Tyrolean Center passengers, cargo, mail B 16/04/2003 AFS Alpine Flightservice GmbH Wallenmahd 23, 6850 Dornbirn passengers, cargo, mail B 20/08/2015 Air Independence GmbH 5020 Salzburg, Airport, Innsbrucker Bundesstraße 95 passengers, cargo, mail A 22/01/2009 Airlink Luftverkehrsgesellschaft m.b.H. 5035 Salzburg-Flughafen - Innsbrucker Bundesstraße 95 passengers, cargo, mail A 31/03/2005 Alpenflug Gesellschaft m.b.H.& Co.KG. 5700 Zell am See passengers, cargo, mail B 14/08/2008 Altenrhein Luftfahrt GmbH Office Park 3, Top 312, 1300 Wien-Flughafen passengers, cargo, mail A 24/03/2011 Amira Air GmbH Wipplingerstraße 35/5. OG, 1010 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 12/09/2019 Anisec Luftfahrt GmbH Office Park 1, Top B04, 1300 Wien Flughafen passengers, cargo, mail A 09/07/2018 ARA Flugrettung gemeinnützige GmbH 9020 Klagenfurt - Grete-Bittner-Straße 9 passengers, cargo, mail A 03/11/2005 ART Aviation Flugbetriebs GmbH Porzellangasse 7/Top 2, 1090 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 14/11/2012 Austrian Airlines AG 1300 Wien-Flughafen - Office Park 2 passengers, cargo, mail A 10/09/2007 Disclaimer: The table reflects the data available in ACOL-database on 16/10/2020. The data is provided by the Member States. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy or the completeness of the data included in this document nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. 1 Active Licenses Decision Name of air carrier Address of air carrier Permitted to carry Category (1) effective since 5020 Salzburg-Flughafen - Innsbrucker Bundesstraße AVAG AIR GmbH für Luftfahrt passengers, cargo, mail B 02/11/2006 111 Avcon Jet AG Wohllebengasse 12-14, 1040 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 03/04/2008 B.A.C.H. -

IATA Airline Designators Air Kilroe Limited T/A Eastern Airways T3 * As Avies U3 Air Koryo JS 120 Aserca Airlines, C.A

Air Italy S.p.A. I9 067 Armenia Airways Aircompany CJSC 6A Air Japan Company Ltd. NQ Arubaanse Luchtvaart Maatschappij N.V Air KBZ Ltd. K7 dba Aruba Airlines AG IATA Airline Designators Air Kilroe Limited t/a Eastern Airways T3 * As Avies U3 Air Koryo JS 120 Aserca Airlines, C.A. - Encode Air Macau Company Limited NX 675 Aserca Airlines R7 Air Madagascar MD 258 Asian Air Company Limited DM Air Malawi Limited QM 167 Asian Wings Airways Limited YJ User / Airline Designator / Numeric Air Malta p.l.c. KM 643 Asiana Airlines Inc. OZ 988 1263343 Alberta Ltd. t/a Enerjet EG * Air Manas Astar Air Cargo ER 423 40-Mile Air, Ltd. Q5 * dba Air Manas ltd. Air Company ZM 887 Astra Airlines A2 * 540 Ghana Ltd. 5G Air Mandalay Ltd. 6T Astral Aviation Ltd. 8V * 485 8165343 Canada Inc. dba Air Canada rouge RV AIR MAURITIUS LTD MK 239 Atlantic Airways, Faroe Islands, P/F RC 767 9 Air Co Ltd AQ 902 Air Mediterranee ML 853 Atlantis European Airways TD 9G Rail Limited 9G * Air Moldova 9U 572 Atlas Air, Inc. 5Y 369 Abacus International Pte. Ltd. 1B Air Namibia SW 186 Atlasjet Airlines Inc. KK 610 ABC Aerolineas S.A. de C.V. 4O * 837 Air New Zealand Limited NZ 086 Auric Air Services Limited UI * ABSA - Aerolinhas Brasileiras S.A. M3 549 Air Niamey A7 Aurigny Air Services Limited GR 924 ABX Air, Inc. GB 832 Air Niugini Pty Limited Austrian Airlines AG dba Austrian OS 257 AccesRail and Partner Railways 9B * dba Air Niugini PX 656 Auto Res S.L.U.