Universita' Degli Studi Di Padova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

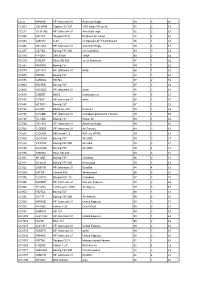

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Skyteam Timetable Covers Period: 01 Jun 2021 Through 31 Aug 2021

SkyTeam Timetable Covers period: 01 Jun 2021 through 31 Aug 2021 Regions :Europe - Asia Pacific Contact Disclaimer To book, contact any SkyTeam member airline. The content of this PDF timetable is for information purposes only, subject to change at any time. Neither Aeroflot www.aeroflot.com SkyTeam, nor SkyTeam Members (including without Aerolneas Argentinas www.aerolineas.com limitation their respective suppliers) make representation Aeromexico www.aeromexico.com or give warranty as to the completeness or accuracy of Air Europa www.aireuropa.com such content as well as to its suitability for any purpose. Air France www.airfrance.com In particular, you should be aware that this content may be incomplete, may contain errors or may have become Alitalia www.alitalia.com out of date. It is provided as is without any warranty or China Airlines www.china-airlines.com condition of any kind, either express or implied, including China Eastern www.ceair.com but not limited to all implied warranties and conditions of China Southern www.csair.com merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, title and Czech Airlines www.czechairlines.com non-infringement. Given the flexible nature of flight Delta Air Lines www.delta.com schedules, our PDF timetable may not reflect the latest information. Garuda Indonesia www.garuda-indonesia.com Kenya Airways www.kenya-airways.com By accessing the PDF timetable, the user acknowledges that the SkyTeam Alliance and any SkyTeam member KLM www.klm.com airline will not be responsible or liable to the user, or any -

Key Data on Sustainability Within the Lufthansa Group Issue 2012 Www

Issue 2012 Balance Key data on sustainability within the Lufthansa Group www.lufthansa.com/responsibility You will fi nd further information on sustainability within the Lufthansa Group at: www.lufthansa.com/responsibility Order your copy of our Annual Report 2011 at: www.lufthansa.com/investor-relations The new Boeing 747-8 Intercontinental The new Boeing 747-8 Intercontinental is the advanced version of one of the world’s most successful commercial aircraft. In close cooperation with Lufthansa, Boeing has developed an aircraft that is optimized not only in terms of com- fort but also in all dimensions of climate and environmental responsibility. The fully redesigned wings, extensive use of weight-reducing materials and innova- tive engine technology ensure that this aircraft’s eco-effi ciency has again been improved signifi cantly in comparison with its predecessor: greater fuel effi - ciency, lower emissions and signifi cant noise reductions (also see page 27). The “Queen of the Skies,” as many Jumbo enthusiasts call the “Dash Eight,” offers an exceptional travel experience in all classes of service, especially in the exclusive First Class and the entirely new Business Class. In this way, environmental effi ciency and the highest levels of travel comfort are brought into harmony. Lufthansa has ordered 20 aircraft of this type. Editorial information Published by Deutsche Lufthansa AG Lufthansa Group Communications, FRA CI Senior Vice President: Klaus Walther Concept, text and editors Media Relations Lufthansa Group, FRA CI/G Director: Christoph Meier Bernhard Jung Claudia Walther in cooperation with various departments and Petra Menke Redaktionsbüro Design and production organic Marken-Kommunikation GmbH Copy deadline 18 May 2012 Photo credits Jens Görlich/MO CGI (cover, page 5, 7, 35, 85) SWISS (page 12) Brussels Airlines (page 13) Reto Hoffmann (page 24) AeroLogic (page 29) Fraport AG/Stefan Rebscher (page 43) Werner Hennies (page 44) Ulf Büschleb (page 68 top) Dr. -

Senato Della Repubblica Viii Legislatura

SENATO DELLA REPUBBLICA VIII LEGISLATURA 1498 SEDUTA PUBBLICA RESOCONTO STENOGRAFICO MARTEDì 8 LUGLIO 1980 Presidenza del vice presidente OSSICINI, indi del vice presidente FERRALASCO INDICE AUTORIZZAZIONI A PROCEDERE IN GIU. INTERPELLANZE E INTERROGAZIONI DIZIO Annunzio Pag. 7934 Trasmissione di domanda Pag. 7895 Annunzio di interrogazione, già assegnata a Commissione permanente, da svolgere CONGEDI . 7893 in Assemblea . 7896 Annunzio di risposte scritte ad interroga- CONSIGLIO NAZIONALE DELL'ECONOMIA zioni . 7934 E DEL LAVORO Svolgimento: Trasmissione di osservazioni e proposte 7895 PRESIDENTE . 7902 e passim · CHIAROMONTE(PCI) . 7906 CORTE COSTITUZIONALE CORALLO(PCI) . .7909, 7921 FERMARIELLO(PCI) . 7896, 7901 Ordinanze emesse da autorità giurisdizio- .. FIORI(Sin. Ind.) . .. ..7912, 7933 nali per il giudizio di legittimità . 7896 FORMICA,ministro dei trasporti . .7913, 7933 GIANNINI, ministro senza portafoglio per CORTE DEI CONTI la funzione pubblica . 7899 GUALTIERI (PR!) 7926 Trasmissione di decisione sul rendiconto MANCA,ministro del commercio con l'estero 7903 generale dello Stato . 7895 7905 MEZZAPESA (DC) . 7924 PARRINO (PSDI) . 7930 DISEGNI DI LEGGE POZZO (MSI-DN) 7928 Annunzio di presentazione . .7893, 7934 SAPORITO(DC) . 7903 SIGNORI (PS/) . 7923 Deferimento a Commissione permanente in SPADACCIA(Misto-PR) 7920 sede deliberante .. 7894 .. SPANO (PSI) 7931 VINCELLI (DC) 7927 Deferimento a Commissioni permanenti in sede referente . 7894 ORDINE DEL GIORNO PER LA SEDUTA DI Presentazione di relazioni . 7895, 7934 MERCOLEDI' 9 LUGLIO 1980 . 7938 Richiesta di parere a Commissione perma- nente . 7895 N. B. ~ L'asterisco indica che il testo del di- Trasmissione dalla Camera dei deputati . 7893 scorso non è stato restituito corretto dall'oratore. TJPOGRA.11JA DEL Së.NATO 0200\ ~ Senato della Repubblica ~ 7893 ~ VIII Legislatura 149a SEDUTA ASSEMBLEA - RESOCONTO STENOGRAFICO 8 LUGLIO 1980 Presidenza del vice presidente O S S I C I N I P R E S I D E N T E. -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

Regulamento (Ue) N

11.2.2012 PT Jornal Oficial da União Europeia L 39/1 II (Atos não legislativos) REGULAMENTOS o REGULAMENTO (UE) N. 100/2012 DA COMISSÃO de 3 de fevereiro de 2012 o que altera o Regulamento (CE) n. 748/2009, relativo à lista de operadores de aeronaves que realizaram uma das atividades de aviação enumeradas no anexo I da Diretiva 2003/87/CE em ou após 1 de janeiro de 2006, inclusive, com indicação do Estado-Membro responsável em relação a cada operador de aeronave, tendo igualmente em conta a expansão do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União aos países EEE-EFTA (Texto relevante para efeitos do EEE) A COMISSÃO EUROPEIA, 2003/87/CE e é independente da inclusão na lista de operadores de aeronaves estabelecida pela Comissão por o o força do artigo 18. -A, n. 3, da diretiva. Tendo em conta o Tratado sobre o Funcionamento da União Europeia, (5) A Diretiva 2008/101/CE foi incorporada no Acordo so bre o Espaço Económico Europeu pela Decisão o Tendo em conta a Diretiva 2003/87/CE do Parlamento Europeu n. 6/2011 do Comité Misto do EEE, de 1 de abril de e do Conselho, de 13 de Outubro de 2003, relativa à criação de 2011, que altera o anexo XX (Ambiente) do Acordo um regime de comércio de licenças de emissão de gases com EEE ( 4). efeito de estufa na Comunidade e que altera a Diretiva 96/61/CE o o do Conselho ( 1), nomeadamente o artigo 18. -A, n. 3, alínea a), (6) A extensão das disposições do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União, no setor da aviação, aos Considerando o seguinte: países EEE-EFTA implica que os critérios fixados nos o o termos do artigo 18. -

Compagnie Aeree Italiane

Compagnie aeree Italiane - Dati di traffico - Flotta - Collegamenti diretti - Indici di bilancio 117 118 Tav. VET 1 Compagnie aeree italiane di linea e charter - traffico 2006 COMPAGNIE Passeggeri trasportati (n.) % Riempimento Ore volate (n.) Voli (n.) Var. Var. Var. (base operativa) 2005 2006 2005 2006 Diff. 2005 2006 2005 2006 % % % attività own risk 44.283 43.452 - 1,9 57 592 2.322 2.433 4,8 1.559 1.594 2,2 Air Dolomiti (1) (Verona) voli operati con 1.248.314 1.421.539 13,9 60 633 45.922 45.757 - 0,4 35.007 33.215 - 5,1 Lufthansa Air Italy 139.105 206.217 48,2 80 800 3.333 5.358 60,8 832 1.385 66,5 (Milano Malpensa) Air One Air One Cityliner 5.264.846 5.662.595 7,6 58 580 77.361 86.189 11,4 63.817 71.161 11,5 Air One Executive (Roma Fiumicino) Air Vallèe 27.353 41.072 50,2 83 54- 29 1.540 2.024 31,4 1.422 2.486 74,8 (Aosta) Alitalia voli di linea 24.196.262 24.453.123 1,1 65 661 551.337 533.389 - 3,3 275.430 263.924 - 4,2 Alitalia Express (Roma Fiumicino) voli charter 122.169 150.652 23,3 79 75- 4 2.052 2.420 17,9 892 1.241 39,1 Alpi Eagles 1.115.079 969.430 - 13,1 58 580 24.806 27.234 9,8 16.891 18.499 9,5 (Venezia) Blue Panorama Airlines Blue Express 1.020.644 1.199.340 17,5 77 803 31.330 32.934 5,1 7.230 11.289 56,1 (Roma Fiumicino) Clubair S.p.A. -

Aeroporti Del Mezzogiorno

AEROPORTI DEL MEZZOGIORNO 2007 AEROPORTI DEL MEZZOGIORNO 2007 Alessandro Bianchi Ministro dei Trasporti Ho trascorso quasi trent’anni della mia vita in Calabria e a Reggio Calabria in particolare. Sono stati anni che ho interamente dedicato allo studio e alla pianifica- zione del territorio, per cui ho ben presente l’importanza di un efficiente sistema di mobilità per l’Italia meridionale e insulare. Le regioni dell’Italia del Sud sono attualmente dotate di un sistema aeroportua- le moderno e quindi lo sforzo che bisogna compiere è in direzione della piena inte- grazione con le reti di trasporto europee, affinché il Mezzogiorno d’Italia diventi la vera testa di ponte continentale verso i paesi della riva sud ed est del Mediter- raneo. Un vasto piano di interventi infrastrutturali negli aeroporti dell’Italia meridionale è in corso di attuazione in esecuzione di Accordi di programma quadro per il tra- sporto aereo sottoscritti con le singole regioni. Sono il frutto di una efficace collabo- razione istituzionale tra l’Unione Europea, che li ha finanziati con i fondi strutturali, le regioni, che hanno impegnato importanti contributi, e il Ministero dei Trasporti e delle Infrastrutture impegnato a centrare l’obiettivo di rendere migliore servizio al cittadino-utente. Comunque è l’intero panorama del trasporto aereo dell’Italia meri- dionale che potrebbe uscire profondamente rinnovato grazie agli interventi del PON Trasporti. Dal punto di vista territoriale la geografia articolata dell’Italia rende prioritarie le esigenze di consolidamento di un vasto network senza privilegiare solo le tratte più redditizie, e la continuità territoriale è prerequisito irrinunciabile perché l’Europa sia veramente unita e perché le barriere geografiche non si trasformino in ostacoli allo sviluppo economico. -

DHL and Leipzig Now Lead ATM Stats 3 European Airline Operations in April According to Eurocontrol

Issue 56 Monday 20 April 2020 www.anker-report.com Contents C-19 wipes out 95% of April air traffic; 1 C-19 wipes out 95% of April air traffic; DHL and Leipzig now lead movements statistics in Europe. DHL and Leipzig now lead ATM stats 3 European airline operations in April according to Eurocontrol. The coronavirus pandemic has managed in the space of a According to the airline’s website, Avinor has temporarily month to reduce European air passenger travel from roughly its closed nine Norwegian airports to commercial traffic and 4 Alitalia rescued (yet again) by Italian normal level (at the beginning of March) to being virtually non- Widerøe has identified alternatives for all of them, with bus government; most international existent (at the end of March). Aircraft movement figures from transport provided to get the passengers to their required routes from Rome face intense Eurocontrol show the rapid decrease in operations during the destination. competition; dominant at Milan LIN. month. By the end of the month, flights were down around Ryanair still connecting Ireland and the UK 5 Round-up of over 300 new routes 90%, but many of those still operating were either pure cargo flights (from the likes of DHL and FedEx), or all-cargo flights Ryanair’s current operating network comprises 13 routes from from over 60 airlines that were being operated by scheduled airlines. Ireland, eight of which are to the UK (from Dublin to supposed to have launched during Birmingham, Bristol, Edinburgh, Glasgow, London LGW, London the last five weeks involving Leipzig/Halle is now Europe’s busiest airport STN and Manchester as well as Cork to London STN). -

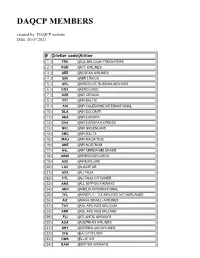

DAQCP MEMBERS Created By: DAQCP Website Date: 20.07.2021

DAQCP MEMBERS created by: DAQCP website Date: 20.07.2021 # 3-letter code Airline 1 FRH ACE BELGIUM FREIGHTERS 2 RUN ACT AIRLINES 3 AEE AEGEAN AIRLINES 4 EIN AER LINGUS 5 AFL AEROFLOT RUSSIAN AIRLINES 6 BOX AEROLOGIC 7 KZR AIR ASTANA 8 BTI AIR BALTIC 9 ACI AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 10 DLA AIR DOLOMITI 11 AEA AIR EUROPA 12 OVA AIR EUROPA EXPRESS 13 GRL AIR GREENLAND 14 AMC AIR MALTA 15 MAU AIR MAURITIUS 16 ANE AIR NOSTRUM 17 ASL AIR SERBIA BELGRADE 18 ABW AIRBRIDGECARGO 19 AXE AIREXPLORE 20 LAV ALBASTAR 21 AZA ALITALIA 22 CYL ALITALIA CITYLINER 23 ANA ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS 24 AEH AMELIA INTERNATIONAL 25 TFL ARKEFLY - TUI AIRLINES NETHERLANDS 26 AIZ ARKIA ISRAELI AIRLINES 27 TAY ASL AIRLINES BELGIUM 28 ABR ASL AIRLINES IRELAND 29 FLI ATLANTIC AIRWAYS 30 AUA AUSTRIAN AIRLINES 31 AHY AZERBAIJAN AIRLINES 32 CFE BA CITYFLYER 33 BMS BLUE AIR 34 BAW BRITISH AIRWAYS 35 BEL BRUSSELS AIRLINES 36 GNE BUSINESS AVIATION SERVICES GUERNSEY LTD 37 CLU CARGOLOGICAIR 38 CLX CARGOLUX AIRLINES INTERNATIONAL S.A 39 ICV CARGOLUX ITALIA 40 CEB CEBU PACIFIC 41 BCY CITYJET 42 CFG CONDOR FLUGDIENST GMBH 43 CTN CROATIA AIRLINES 44 CSA CZECH AIRLINES 45 DLH DEUTSCHE LUFTHANSA 46 DHK DHL AIR LTD. 47 EZE EASTERN AIRWAYS 48 EJU EASYJET EUROPE 49 EZS EASYJET SWITZERLAND 50 EZY EASYJET UK 51 EDW EDELWEISS AIR 52 ELY EL AL 53 UAE EMIRATES 54 ETH ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 55 ETD ETIHAD AIRWAYS 56 MMZ EUROATLANTIC 57 BCS EUROPEAN AIR TRANSPORT 58 EWG EUROWINGS 59 OCN EUROWINGS DISCOVER 60 EWE EUROWINGS EUROPE 61 EVE EVELOP AIRLINES 62 FIN FINNAIR 63 FHY FREEBIRD AIRLINES 64 GJT GETJET AIRLINES 65 GFA GULF AIR 66 OAW HELVETIC AIRWAYS 67 HFY HI FLY 68 HBN HIBERNIAN AIRLINES 69 HOP HOP! 70 IBE IBERIA 71 ICE ICELANDAIR 72 ISR ISRAIR AIRLINES 73 JAL JAPAN AIRLINES CO. -

Check-In Am Bahnhof Und Fly Rail Baggage

1/8 Check-in am Bahnhof via Zürich und Genève Check-in à la gare via Zürich et Genève Check-in alla stazione via Zürich e Genève Check-in at the railstation via Zürich and Genève Version: 26. Januar 2011 Legend HA = Handlingagent SP = Swissport, DN = Dnata Switzerland AG, AS = Airline Assistance Switzerland AG, EH = Own Handling R = Reason T = Technical, S = Security, O = Other reason WT = Weight Tolerance Y = Economy-Class, C = Business-Class, F = First-Class * = Agent Informations Infoportal/Airlines Check-in ok Restrictions Airline, Code Check-in Einschränkungen/Restrictions WT HA R Y = 2 Adria Airways JP ok SP C = 3 Aegean Airlines A3 ok 2 SP Aer Lingus EI no SP O Aeroflot Russian Airlines SU no SP S Aerolineas Argentinas AR ok 2 SP African Safari Airways ASA ok 2 DN Afriqiyah Airways 8U no DN O Air Algérie* AH ok No boardingpass 0 SP Air Baltic BT no SP T Not for USA, Canada, Pristina, Russia, Air Berlin* AB ok Cyprus; 0 DN not possible for groups 11+ Air Cairo MSC ok 2 SP AC 6821 / 6822 / 6826 / 6829 / 6832 / Air Canada AC no SP T =ok Air Dolomiti EN ok 2 SP Air Europa AEA / UX ok 2 DN Not from Zürich; not for USA, Canada, AF ok* 2 SP T Air France* Mexico; no boardingpass Air India AI ok 2 SP Air Italy I9 ok 2 DN Air Mali XG no SP O Air Malta KM ok 3 SP Y = 7 Air Mauritius MK ok Not from Zurich SP C = 10 Air Mediteranée BIE ok 2 DN Air New Zealand NZ ok 2 SP Air One AP ok 2 SP Air Seychelles HM ok Not from Zurich 3 SP Air Transat TS ok 2 SP Alitalia AZ no SP/DN T American Airlines AA no SP T ANA All Nippon Airways NH ok 2 SP Armavia