A Qualitative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly District Report

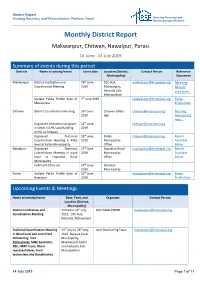

District Report Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform Monthly District Report Makwanpur, Chitwan, Nawalpur, Parasi 14 June - 14 July 2019 Summary of events during this period Districts Name of activity/event Event date Location (District, Contact Person Reference Municipality) Document Makwanpur District Facilitation and 18th June DCC Hall, [email protected] Meeting Coordination Meeting 2019 Makwanpur, Minute Hetauda Sub- click here.. Metropolitan Update Palika Profile data of 7th June 2019 [email protected] Palika Makwanpur Profile Data Chitwan District Coordination Meeting 26th June Chitwan GMaLi [email protected] Meeting 2019 Hall Minute click here... Organized interaction program 24th June, [email protected] in GMALI DLPIU and Building 2019 DLPIU at Chitwan Organized Technical 26th june, Kalika [email protected] Report Coordination Meeting in Plika 2019 Municipality Available level at Kalika Municipality Office Below Nawalpur Organized Technical 27th June Hupsekot Rural [email protected] Report Coordination Meeting in ward 2019 Municipality Available level at Hupsekot Rural Office Below Municipality Field visit Carry out 27th June, Devchuli 2019 Municipality Parasi Update Palika Profile data of 12th June [email protected] Palika Nawalpur 2019 Profile Data Upcoming Events & Meetings Name of activity/event Date, Time, and Organizer Contact Person Location (District, Municipality) District Facilitation and Tentative 19th July, DCC/GMaLI/HRRP [email protected] Coordination Meeting 2019; DCC Hall, Hetauda, Makwanpur Technical Coordination Meeting 24th July to 26th July, Joint Monitoring Team [email protected] in Ward level and Joint Field 2019 Bakaiya Rural Monitoring Visit Municipality, Participants: M&E Specialist, Makwanpur Gadhi DSE, HRRP team, Ward and Hetauda Sub- representatives, local Metropolitan technicians and Beneficiaries. -

Sja V 18 I 1 2020.Pdf

SAARC JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURE (SJA) Volume 18, Issue 1, 2020 ISSN: 1682-8348 (Print), 2312-8038 (Online) © SAC The views expressed in this journal are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of SAC Published by SAARC Agriculture Centre (SAC) BARC Complex, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh Phone: 880-2-8141665, 8141140; Fax: 880-2-9124596 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.banglajol.info/index.php/SJA/index Editor-in-Chief Dr. Mian Sayeed Hassan Director, SAARC Agriculture Centre BARC Complex, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh Managing Editor Dr. Ashis Kumar Samanta Senior Program Specialist, SAARC Agriculture Centre BARC Complex, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh Associate Editor Fatema Nasrin Jahan Senior Program Officer, SAARC Agriculture Centre BARC Complex, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh Printed at Natundhara Printing Press, 277/3, Elephant Road, Dhaka-1205, Bangladesh Cell: 01711019691, 01911294855, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 1682-8348 (Print), 2312-8038 (Online) SAARC JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURE VOLUME 18 ISSUE 1 JUNE 2020 SAARC Agriculture Centre www.sac.org.bd EDITORIAL BOARD Editor-in-Chief Dr. Mian Sayeed Hassan Director, SAARC Agriculture Centre BARC Complex, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh Managing Editor Dr. Ashis Kumar Samanta Senior Program Specialist, SAARC Agriculture Centre BARC Complex, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh Associate Editor Fatema Nasrin Jahan Senior Program Officer, SAARC Agriculture Centre BARC Complex, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh Members Dr. M. Jahiruddin Dr. Muhammad Musa Professor Deputy Director (Research) Department of Soil Science, Faculty of Ayub Agricultural Research Institute Agriculture, Bangladesh Agricultural Faisalabad, Pakistan University, Mymensingh, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dr. -

Provincial Summary Report Province 3 GOVERNMENT of NEPAL

National Economic Census 2018 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 Provincial Summary Report Provincial National Planning Commission Province 3 Province Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 Published by: Central Bureau of Statistics Address: Ramshahpath, Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. Phone: +977-1-4100524, 4245947 Fax: +977-1-4227720 P.O. Box No: 11031 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-0-6360-9 Contents Page Map of Administrative Area in Nepal by Province and District……………….………1 Figures at a Glance......…………………………………….............................................3 Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Province and District....................5 Brief Outline of National Economic Census 2018 (NEC2018) of Nepal........................7 Concepts and Definitions of NEC2018...........................................................................11 Map of Administrative Area in Province 3 by District and Municipality…...................17 Table 1. Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Sex and Local Unit……19 Table 2. Number of Establishments by Size of Persons Engaged and Local Unit….….27 Table 3. Number of Establishments by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...34 Table 4. Number of Person Engaged by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...48 Table 5. Number of Establishments and Person Engaged by Whether Registered or not at any Ministries or Agencies and Local Unit……………..………..…62 Table 6. Number of establishments by Working Hours per Day and Local Unit……...69 Table 7. Number of Establishments by Year of Starting the Business and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...77 Table 8. -

HRRP Bulletin Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal

Media Digest | FAQ | Briefing Pack | Meeting & Events | 5W | Housing Progress | Housing Typologies Women masons engaged in the housing reconstruction of earthquake beneficiaries after the graduation of masons training organized in Ward no. 9, Palungtar Municipality of Gorkha, organized by Government of India supported Nepal Housing Reconstruction Project in the district. (Photo credit: Mr. Ram Sapkota, District Coordinator, Nepal Housing Reconstruction Project, Gorkha) HRRP Bulletin Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal HIGHLIGHTS ● HRRP Partner Satisfaction Survey ● NRA Notice on the Final Tranche disbursement deadline ● Urban Webinar on “Leadership of Municipal Government for Urban Recovery and Development” ● Workshop on NRA's Best Practices on Private Housing Retrofitting Experience and Way Forward ● Economic Impact Study ● COVID-19 live updates from Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) FEATURED TECHNICAL STAFF STORY: Laxmi Pathak, Mobile Mason, Ward no 9, Manahari Rural Municipality, Makwanpur Laxmi Pathak, Mobile Mason, Manahari Rural Municipality - 9, Makwanpur Breaking all the gender stereotypes, Ms. Laxmi Pathak from Manahari Rural Municipality, Makwanpur district is a staff member serving NRA DLPIU Building Office as a mobile mason. Pathak started working as a mobile mason from January 2020 and is based in Ward no. 9 of the Rural Municipality. During the initial days of the reconstruction, female masons were given less priority in the community. Pathak shared that the community Laxmi Pathak, used to doubt the ability of female masons, Mobile Mason because of which the beneficiaries did not Manahari Rural Municipality - 9, properly follow the instructions or guidance Makwanpur given by female masons. When villagers saw female masons like herself carrying sand, bricks, and cement to dig a foundation with confidence and aura, they also started to believe in the 22 February 2021 Page 2 of 24 HRRP Bulletin Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal female mason’s capacity like they did for male masons. -

Ministry of Finance Financial Comptroller General Office Anamnagar, Kathmandu

An Integrated Financial Code, Classification and Explanation 2074 B.S (Second Revision) Government of Nepal Ministry of Finance Financial Comptroller General Office Anamnagar, Kathmandu WWW.fcgo.gov.np Approved for the operation of economic transaction of three level of government pursuant to the federal structure. Integrated Financial Code, Classification and Explanation, 2074 (Second Revision) (Date of approval by Financial Comptroller General: 2076/02/15) Government of Nepal Ministry of Finance Financial Comptroller General Office Anamnagar, Kathmandu Table of Contents Section – One Budget and Management of Office Code 1 Financial code and classification, and basis of explanation and implementation system 1.1 Budget Code of Government of Nepal 1.2 Office Code of expenditure units of Government of Nepal 1.3 Office Code of the Ministry/organizations of Provincial Government 1.4 Office Code of Local Level 1.5 Code indicating the nature of expenditure 1.6 Code of Donor Agency 1.7 Mode of Receipt/Payment 1.8 Budget Service and Functional Classification 1.9 Code of Province and District Section – Two Classification of Integrated Financial Code and Explanation 2.1 Code of Revenue, classification and explanation 2.2 Code of current expenditure, classification and explanation 2.3 Code of Capital expenditure/assets and liability, classification and explanation 2.4 Code of financial assets and liability (Financial System), classification and explanation 2.5 Code of the balance of assets and liability, description and explanation Section – Three Budget Sub-head of local level Part– one Management of Budget and Office Code 1. The basis of financial code and classification and explanation and its system of implementation The constitution of Nepal has made provision for a separate treasury fund in all three levels of government (Federal, Province and Local), and accounting format for economic transaction as approved by the auditor general. -

Institution and Scale of Ecosystem Service Governance in Nepal a Case of Kulekhani Area 1

Institution and scale of ecosystem service governance in Nepal A case of Kulekhani Area 1. Navaraj Pokharel Prince of Songkla University Faculty of Environment and Energy , Thailand 2. Yogendra Raj Rijal Ph D. Parbat, Nepal Abstract New actors with different agendas and ideas are now emerging and playing important role in decision-making about ecosystem service governance. Network types of governance has been practicing in all sectors including in conservation. Awareness about key ideas of environmental governance or protection and use of natural resources among local people is the important concern today. Nepal's efforts in ecosystem service governance in the last three decades are noteworthy but the results are far from satisfaction. Coordination among various actors is the main problem in ES governance. Due to the lack of locally elected representative in Local Bodies (LBs) since before 15 years, coordination among actors and taking decision with strategic vision has some problems. Duplication in the use of resources is high, controlling and monitoring system is weak. Institutions are weaken and no more attention is given to rural people who are traditionally depend on natural resources for their livelihoods. This paper tries to explore the key environmental governance issues relevant to the conservation with specific reference to institutional fit and scale. Key Words : ecosystem services, Kulekhaani, Watershed, Nepal etc. 1. Introduction Ecosystem service governance is one of the major crosscuttings in contemporary development agenda. Significant efforts have been taken by the state and non-state actors to protect environmental elements in the world today. However, ecosystem services are becoming increasingly threatened globally.This trend is partially due to the lack of appreciation of their value. -

1 Government of Nepal National Reconstruction Authority Central

Government of Nepal National Reconstruction Authority Central Level Project Implementation Unit District Level Project Implementation Unit (Grant Management and Local Infrastructure) Makwanpur Environmental and Social Management Plan of Mathilo DamarSupply Rehabilitation, Bhimphedi Rural municipality FY: 075/76 1 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives of ESMP ............................................................................................................ 4 Site Description ................................................................................................................... 4 Environmental and Social Issues ........................................................................................ 4 Environment and Social Management Plan (ESMP) .......................................................... 5 Monitoring and evaluation .................................................................................................. 6 Occupation health and safety measures .............................................................................. 6 ESMP Cost .......................................................................................................................... 6 Conclusion ......................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Annex 1 .............................................................................................................................. -

Terms of Reference (TOR)

Terms of Reference (TOR) Invitation for expression of interest (EOI) for partnership to implement Sponsorship Communication program in Makwanpur district Nepal 1. Introduction: Plan International is an independent development and humanitarian organization that advances children’s rights and equality for girls. We believe in the power and potential of every child. But this is often suppressed by poverty, violence, exclusion and discrimination. And it is the girls who are most affected. Working together with children, young people, our supporters and partners, we strive for a just world, tackling the root causes of the challenges facing girls and all vulnerable children. We support children’s rights from birth until they reach adulthood. And we enable children to prepare for – and respond to – crises and adversity. We drive changes in practice and policy at local, national and global levels using our reach, experience and knowledge. We have been building powerful partnerships for children for 80 years, and are now active in more than 70 countries. Plan International has been working in Nepal since 1978, helping marginalized children, their families and communities to access their rights to health, hygiene and sanitation, basic education, economic security of young people, protection and safety from disasters. Through partner NGOs, community based organizations and government agencies, Plan International Nepal reaches over 42 districts. The refreshed country strategy (2020 to 2023) of Plan International Nepal sets out a bold and clear vision of an inclusive, just and safe society where all girls and young women enjoy their rights and live in freedom. In line with Plan International’s global strategy “100 Million Reasons” and the regional ambition to reach 7% of all girls in the countries where Plan works, Plan International will reach 500,000 girls directly and 1 million girls indirectly in Nepal. -

Situation Update of Bagmati Province Makawanpur, 30 April

Corona Virus: Situation Update of Bagmati Province Makawanpur, 30 April, 2020 Ministry of Social Development has ordered schools to publish yearly results of 1 to 9 grade examination which was stopped due to the lock down. The ministry also directed to provide text books by maintaining social distancing. In addition, schools were requested to create the learning opportunities for students through online and offline platforms. According to the District Representative of Sindhipalchok, Natibabu Dhital, swab collection booth has been established in primary health centres of Barhabishe and Melamchi in order to exemine covid-19. Jugal rural municipality has decided to organize admission campaigns and distribution text books to the students. According to the District Representative of Dhading, Sitaram Adhikari, Nepal Engineers’ Association Bagmati has distributed swab collection booth to Dhading district hospital. Relief materials have been distributed in Benighat Rorang rural municipality to 40 families of Chepang community. According to the District Representative of Dolakha, Uddhav Pokharel, Sailung rural municipality has established Corona Virus Prevention and Control fund with 3 million NPR amount and provided 1 lakh to each ward in order to carry out corona virus prevention activities. Likewise, rural municipality also provided 75,000 NPR to each health institutions and police posts. Rural municipality decided to give 10,000 NPR treatment money and free ambulance service to covid-19 infected person, and 1 lakh to front line workers. According to the District Representative of Makawanpur, Pushparaj Adhikari, it has been found that by covering up the opportunity of lock down wholesellers and retailers have increased the price of food grains. -

Assessment of Rock Slope Stability in Kulekhani Watershed, Central Nepal

Bulletin of Nepal Geological Society, 2018, vol. 35 Assessment of rock slope stability in Kulekhani watershed, central Nepal Badal Pokharel and *Prem Bahadur Thapa Department of Geology, Tri-Chandra Multiple Campus, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Study area lies in the Kulekhani watershed of central Nepal and comprises metasandstone, phyllite, schist, quartzite and marble. There is a wide variation in slopes in Kulekhani watershed as topographical variance. The watershed has been facing several slope failures during the past decades. The landslides and debris flows were observed mostly on the steep upper reaches of the Kulekhani watershed. Large plane rockslides are found on the slopes west of Phedigaun, where the hillslope angle ranges from 40o to 60o. Kinematic analysis of the slopes was carried out at fifteen different locations of the study area in order to interpret the rock slope stability. At each location, around seventy five measurements of joint orientation were analyzed. The analysis at Palung-Kulekhani area showed the high possibility of toppling failure in phyllites of Kulikhani Formation whereas wedge failure found to be prominent in marble beds of Markhu Formation. Probability of plane failures is seen in Kulikhani and Markhu formations. The slopes with dip angle between 30o and 65o have faced many failures and even further chance of failures is high in these slopes. The haphazard excavation is one of the major reasons for instability along the highway. Other causes are torrential rainfall and differential weathering of rocks in the area. Keywords: Rock slope stability, Kinematic analysis, Kulekhani watershed, Central Nepal INTRODUCTION of the watershed is rugged and consisting of several folds of sloping hills with a number of streams and rivers (Chandra et The potential danger of instability generally occurs at al., 2002). -

Cg";"Lr–1 S.N. Application ID User ID Roll No बिज्ञापन नं. तह पद उम्मेदव

cg";"lr–1 S.N. Application ID User ID Roll No बिज्ञापन नं. तह पद उ륍मेदवारको नाम लऱगं जꅍम लमतत सम्륍मलऱत हुन चाहेको समूह थायी न. पा. / गा.वव.स-थायी वडा नं, थायी म्ज쥍ऱा नागररकता नं. 1 85994 478714 24001 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager ANIL NIROULA Male 2040/01/09 खलु ा Biratnagar-5, Morang 43588 2 86579 686245 24002 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager ARJUN SHRESTHA Male 2037/08/01 खलु ा Bhadrapur-13, Jhapa 1180852 3 28467 441223 24003 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager ARUN DHUNGANA Male 2041/12/17 खलु ा Myanglung-2, Tehrathum 35754 4 34508 558226 24004 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager BALDEV THAPA Male 2036/03/24 खलु ा Sikre-7, Nuwakot 51203 5 69018 913342 24005 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager BHAKTA BAHADUR KHATRI CHATRI Male 2038/12/25 खलु ा PUTALI BAZAR-14, Syangja 49247 6 89502 290954 24006 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager BIKAS GIRI Male 2034/03/15 खलु ा Kathmandu-31, Kathmandu 586/4042 7 6664 100010 24007 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager DINESH GAUTAM Male 2036/03/11 खलु ा Nepalgunj-12, Banke 839 8 62381 808488 24008 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager DINESH OJHA Male 2036/12/15 खलु ा Biratnagar Metropolitan-12, Morang 1175483 9 89472 462485 24009 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager GAGAN SINGH GHIMIRE Male 2033/04/26 खलु ा MAIDAN-3, Arghakhanchi 11944/3559 10 89538 799203 24010 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager GANESH KHATRI Male 2028/07/25 खलु ा TOKHA-5, Kathmandu 4/2161 11 32901 614933 24011 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager KHIL RAJ BHATTARAI Male 2039/08/08 खलु ा Bhaktipur-6, Sarlahi 83242429 12 70620 325027 24012 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager KRISHNA ADHIKARI Male 2038/03/23 खलु ा walling-10, -

Monthly District Report

District Report Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform Monthly District Report Makwanpur, Chitwan, Nawalpur, Parasi 12 July – 22 August 2019 Summary of events during this period Districts Name of activity/event Event date Location (District, Contact Person Reference Municipality) Document Makwanpur Annual Reconstruction Review 18th June DCC Hall, [email protected] Report Workshop 2019 Makwanpur, below Hetauda Sub- Metropolitan Update Palika Profile data of 14th August, [email protected] Palika Makwanpur 2019 Profile Data Contact list updated in GD 25th Contact List August,2019 Chitwan Contact list updated in GD 26th August, [email protected] Contact List 2019 Update Palika Profile data of 15th August, Palika Nawalpur 2019 Profile Data Nawalpur Contact list updated in GD 26th August, [email protected] Contact List 2019 Update Palika Profile data of 15th Palika Nawalpur August,2019 Profile Data Parasi Update Palika Profile data of 15th [email protected] Palika Nawalpur August,2019 Profile Data Upcoming Events & Meetings Name of activity/event Date, Time, and Organizer Contact Person Location (District, Municipality) District Facilitation and Tentative 29th August, DCC/GMaLI/HRRP [email protected] Coordination Meeting 2019; DCC Hall, Hetauda, Makwanpur Organize orientation 10th Sept to 17th Sept, Joint Monitoring Team [email protected] programs about the retrofit 2019 at all municipalities of Makwanpur 22 August 2019 Page 1 of 9 District Report Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform News & Updates NRA-GMaLI-DLPIU, Makwanpur has been completed annual review workshop at district with presence of all municipalities and all stake holders. HRRP- Makwanpur Presentation Slide click here.