Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Every Light in the House Is on Trace Adkins Free Mp3 Download

Every light in the house is on trace adkins free mp3 download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD “Every Light in the House” is a song written by Kent Robbins and recorded by American country music artist Trace Adkins. It was released in August as the second single from his debut. Check out Every Light In The House by Trace Adkins on Amazon Music. Stream ad-free or purchase CD's and MP3s now on renuzap.podarokideal.ru(26). 10/26/ · Every Light In The House Trace Adkins [Intro] F C A# [Verse] F I told you I d leave a light on C In case you ever wanted to come back home A# F C You smiled and said you appreciate the gesture F I took you every word to heart C Cause I can t stand us being apart A# F C And just to show how much I really miss ya [Chorus] F Every light in the house is on C The backyard s bright as the . Trace Adkins Every Light in the House Lyrics More music MP3 download song lyrics: How High the Moon Lyrics, Take Me Back Lyrics, Fools Fall in Love Lyrics, Shooting Star Lyrics, Love Up Lyrics, I'm from the CO Lyrics, Hammer of God Lyrics, Kansas City Lyrics, Few Hours of Light Lyrics, My Devotion Lyrics, Donna the Prima Donna. Download the karaoke of Every Light in the House as made famous by Trace Adkins in the genre Country on Karaoke Version. Every Light in the House Karaoke - Trace Adkins. All MP3 instrumental tracks Instrumentals on demand Latest MP3 instrumental tracks MP3 instrumental tracks Free karaoke files. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Questioning Whiteness: “Who Is White?”

人間生活文化研究 Int J Hum Cult Stud. No. 29 2019 Questioning Whiteness: “Who is white?” ―A case study of Barbados and Trinidad― Michiru Ito1 1International Center, Otsuma Women’s University 12 Sanban-cho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan 102-8357 Key words:Whiteness, Caribbean, Barbados, Trinidad, Oral history Abstract This paper seeks to produce knowledge of identity as European-descended white in the Caribbean islands of Barbados and Trinidad, where the white populations account for 2.7% and 0.7% respectively, of the total population. Face-to-face individual interviews were conducted with 29 participants who are subjectively and objectively white, in August 2016 and February 2017 in order to obtain primary data, as a means of creating oral history. Many of the whites in Barbados recognise their interracial family background, and possess no reluctance for having interracial marriage and interracial children. They have very weak attachment to white hegemony. On contrary, white Trinidadians insist on their racial purity as white and show their disagreement towards interracial marriage and interracial children. The younger generations in both islands say white supremacy does not work anymore, yet admit they take advantage of whiteness in everyday life. The elder generation in Barbados say being white is somewhat disadvantageous, but their Trinidadian counterparts are very proud of being white which is superior form of racial identity. The paper revealed the sense of colonial superiority is rooted in the minds of whites in Barbados and Trinidad, yet the younger generations in both islands tend to deny the existence of white privilege and racism in order to assimilate into the majority of the society, which is non-white. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS MAY 17, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 18 BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] INSIDE Grand Ole Opry Moves Toward The Old Normal THIS As U.S. Reemerges From COVID-19 ISSUE It likely won’t have the shelf life of Throwback Thursdays or In ideal Opry fashion, the lineup reflected a variety of styles Taco Tuesdays, but “full-capacity Friday night” had an oddly and eras. Lorrie Morgan opened with her chart-topping 1990 Sam Hunt’s ‘90’s’ special ring to it on May 14. single “Five Minutes,” and the rest of the talent parade fea- Breaks Out Grand Ole Opry announcer tured current hitmaker Michael Ray, >page 4 Bill Cody uncorked the phrase as Western vocal quartet Riders in the the WSM-AM Nashville show had Sky, comedian Aaron Weber, Nash- every ticket in the 4,400-seat Opry ville actor Charles Esten and new- House available for the first time comer Brittney Spencer, who sang Underwood, since March 10, 2020, when the a new song, “Sober & Skinny,” for the Aldean, Brooks coronavirus pandemic forced live first time in public. In Play entertainment off the stage. Some Spencer’s appearance was a >page 10 2,400 tickets were sold, according personal milestone, for she made to Opry vp/executive producer Dan her Opry debut. While she felt its Rogers, as the reboot coincided significance (she conceded that her with an unexpected bonus: Barely breathing was more pronounced Makin’ Tracks: 24 hours before the show’s start, the during “Sober” as she fought off a Drew Parker’s city of Nashville dropped face-mask case of nerves), she was still present ‘BP PBR’ Song mandates. -

C a L L a L O O

C A L L A L O O WHAT WE MEAN WHEN WE SAY ‘CREOLE’ An Interview with Salikoko S. Mufwene by Michael Collins Salikoko S. Mufwene is an internationally renowned theorist of language evolution, language contact, and sociolinguistics, among other subjects. He sat for the following interview on April 7 and April 8, 2003, during a visit he paid to Texas A & M University in College Station to lecture on controversies surrounding Ebonics. Mufwene’s ability to dazzle audiences was just as evident in Texas as it had been in the city-state of Singapore, where I first heard him lecture. His ability was indeed already apparent early in his life in Congo: Robert Chaudenson of the Université d’Aix-en-Provence reports that in 1973 “Mufwene received a License en Philosophie et Lettres (with a major in English Philology) from the National University of Zaire at Lubumbashi (with Highest Honors). The same year he also obtained his Agrégation d’enseignement moyen du degré supérieur (with Honors). Let me comment a bit on the significance of these diplomas, especially for readers who are not familiar with (post)colonial Africa. That the young Salikoko, born in Mbaya-Lareme, would find himself twenty years later in Lubumbashi at the University, with not one but two diplomas, should in itself count as an obvious sign of intellectual excellence for anyone who is in any way familiar with the Congo of that era. Salikoko must have seriously distinguished himself among his peers: at that time, overly limited opportunities and a brutally elitist educational system did entail fierce competition.” For the rest of Chaudenson’s remarks, and for further information on Mufwene, see http://humanities.uchicago.edu/faculty/mufwene/index.html. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

1715 Total Tracks Length: 87:21:49 Total Tracks Size: 10.8 GB

Total tracks number: 1715 Total tracks length: 87:21:49 Total tracks size: 10.8 GB # Artist Title Length 01 Adam Brand Good Friends 03:38 02 Adam Harvey God Made Beer 03:46 03 Al Dexter Guitar Polka 02:42 04 Al Dexter I'm Losing My Mind Over You 02:46 05 Al Dexter & His Troopers Pistol Packin' Mama 02:45 06 Alabama Dixie Land Delight 05:17 07 Alabama Down Home 03:23 08 Alabama Feels So Right 03:34 09 Alabama For The Record - Why Lady Why 04:06 10 Alabama Forever's As Far As I'll Go 03:29 11 Alabama Forty Hour Week 03:18 12 Alabama Happy Birthday Jesus 03:04 13 Alabama High Cotton 02:58 14 Alabama If You're Gonna Play In Texas 03:19 15 Alabama I'm In A Hurry 02:47 16 Alabama Love In the First Degree 03:13 17 Alabama Mountain Music 03:59 18 Alabama My Home's In Alabama 04:17 19 Alabama Old Flame 03:00 20 Alabama Tennessee River 02:58 21 Alabama The Closer You Get 03:30 22 Alan Jackson Between The Devil And Me 03:17 23 Alan Jackson Don't Rock The Jukebox 02:49 24 Alan Jackson Drive - 07 - Designated Drinke 03:48 25 Alan Jackson Drive 04:00 26 Alan Jackson Gone Country 04:11 27 Alan Jackson Here in the Real World 03:35 28 Alan Jackson I'd Love You All Over Again 03:08 29 Alan Jackson I'll Try 03:04 30 Alan Jackson Little Bitty 02:35 31 Alan Jackson She's Got The Rhythm (And I Go 02:22 32 Alan Jackson Tall Tall Trees 02:28 33 Alan Jackson That'd Be Alright 03:36 34 Allan Jackson Whos Cheatin Who 04:52 35 Alvie Self Rain Dance 01:51 36 Amber Lawrence Good Girls 03:17 37 Amos Morris Home 03:40 38 Anne Kirkpatrick Travellin' Still, Always Will 03:28 39 Anne Murray Could I Have This Dance 03:11 40 Anne Murray He Thinks I Still Care 02:49 41 Anne Murray There Goes My Everything 03:22 42 Asleep At The Wheel Choo Choo Ch' Boogie 02:55 43 B.J. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. October 12, 2020 to Sun. October 18, 2020

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. October 12, 2020 to Sun. October 18, 2020 Monday October 12, 2020 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT The Day The Rock Star Died The Big Interview Michael Jackson - Michael Jackson was a singer, songwriter, dancer and known simply as “The The Band’s Robbie Robertson - Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson sits down with Dan Rather to talk about King of Pop.” His contributions to music, dance, and highly publicized personal life made him a his five decades as a progressive rock idol. global figure in popular culture for over four decades. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 5:30 PM ET / 2:30 PM PT Deep Purple’s: The Ritchie Blackmore Story A Year in Music From his pop roots with The Outlaws and his many session recordings in the sixties, through 1964 - Actor, writer, and musician, Tommy Chong dives into 1964: the year The Beatles took defining hard rock with Deep Purple and Rainbow in the seventies and eighties and on to the over, Motown Records became a driving force, and The Rolling Stones made their debut. Plus, a renaissance rock of Blackmore’s Night, Ritchie has proved that he is a master of the guitar across look at how political and social changes influenced pop music. a multitude of styles. This is the definitive story of a true guitar legend. 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT 10:20 AM ET / 7:20 AM PT The Big Interview Robert Plant And The Strange Sensation Edward Norton - Academy Award winner Edward Norton’s life is much more than Hollywood. -

Rockin' at Regency Furniture Stadium

Rockin' at Regency Furniture Stadium Posted by TBN On 03/19/2009 The Southern Maryland Blue Crabs have announced a new partnership with Kool Productions LLC, designed to enhance the quality of non-game day events at Regency Furniture Stadium, for the benefit of Charles County and the surrounding communities. The partnership is off to a terrific start, as the team has also announced two major concert events at its stadium this summer. To kick off the summer concert series, ground breaking hip-hop artists T-Pain and Flo Rida will perform at Regency Furniture Stadium on Saturday, June 6. The gates will open at 6 p.m., with the show beginning at 7 p.m. T-Pain burst onto the music scene during the winter of 2005 with his debut album Rappa Ternt Sanga and his first single “I’m Sprung.” In 2007 he released his sophomore album Epiphany featuring more hit singles “Buy U a Drank” (featuring Yung Joc) and “Bartender.” These albums and songs helped establish T-Pain as a leading R&B and hip-hop contemporary artist. Flo Rida has been breaking records with smash-hit singles “Low” (featuring T-Pain) and more recently “Right Round.” These songs made it to the top of nearly every chart, making Flo Rida a household name even before his Atlantic Records album Mail on Sunday was released in 2008. His new album R.O.O.T.S., including the new single “Sugar” is due to be released March 31. Regency Furniture Stadium and Kool Productions will usher in a much different genre of music in July, with another chart topping artist. -

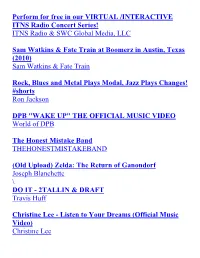

Perform for Free in Our VIRTUAL /INTERACTIVE ITNS Radio Concert Series! ITNS Radio & SWC Global Media, LLC

Perform for free in our VIRTUAL /INTERACTIVE ITNS Radio Concert Series! ITNS Radio & SWC Global Media, LLC Sam Watkins & Fate Train at Boomerz in Austin, Texas (2010) Sam Watkins & Fate Train Rock, Blues and Metal Plays Modal, Jazz Plays Changes! #shorts Ron Jackson DPB "WAKE UP" THE OFFICIAL MUSIC VIDEO World of DPB The Honest Mistake Band THEHONESTMISTAKEBAND (Old Upload) Zelda: The Return of Ganondorf Joseph Blanchette \ DO IT - 2TALLIN & DRAFT Travis Huff Christine Lee - Listen to Your Dreams (Official Music Video) Christine Lee We are One by Nordic Daughter Nordic Daughter Teddy Bop by TSwang Video tswang2 Silent Machines - What Matters The Most Silent Machines Heavy AmericA - "Motor Honey (Peace)" Heavy AmericA "Mary Did You Know" - By Lucas Ciliberti Lucas Ciliberti Waiting Til Dawn "Official Video" PLEASE SUBSCRIBE!! McCUIN *OFFICIAL BAND PAGE* Richard Mulligan and Richard Mulligan on Soap garrisonskunk a few miles down the road Brandon Good Pedal Steel Guitar solo on SAN ANTONIO ROSE John Heinrich show me you vanilla base Vanilla base Guitar Boogie - Arthur Smith DaemonRicks Ali Jacko - Follow My HEART (Official Video) ajackorocksVEVO TK MAFIOSO - " BIGGIE PAC " ( OFFICAL MUSIC VIDEO ) TK Mafioso Illist - What I've Never Felt (Official Music Video) Angels Castle Live - Jimmy Richardson jimjim776 Kayla Cariaga (Kayla C.) - GONE Official Music Video Kayla Cariaga What Do I Know JP Southern Band William T Starzz Going In official video directed by Bryan Eyce Leonard William T. Starzz Johnny Rock Band - Easter Bunny Hop Johnny Rock -

TOP HITS of the EIGHTIES by YEAR 1980’S Top 100 Tracks Page 2 of 31

1980’S Top 100 Tracks Page 1 of 31 TOP HITS OF THE EIGHTIES BY YEAR 1980’S Top 100 Tracks Page 2 of 31 1980 01 Frankie Goes To Hollywood Relax 02 Frankie Goes To Hollywood Two Tribes 03 Stevie Wonder I Just Called To Say I Love You 04 Black Box Ride On Time 05 Jennifer Rush The Power Of Love 06 Band Aid Do They Know It's Christmas? 07 Culture Club Karma Chameleon 08 Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Swing The Mood 09 Rick Astley Never Gonna Give You Up 10 Ray Parker Jr Ghostbusters 11 Lionel Richie Hello 12 George Michael Careless Whisper 13 Kylie Minogue I Should Be So Lucky 14 Starship Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Now 15 Elaine Paige & Barbara Dickson I Know Him So Well 16 Kylie & Jason Especially For You 17 Dexy's Midnight Runners Come On Eileen 18 Billy Joel Uptown Girl 19 Sister Sledge Frankie 20 Survivor Eye Of The Tiger 21 T'Pau China In Your Hand 22 Yazz & The Plastic Population The Only Way Is Up 23 Soft Cell Tainted Love 24 The Human League Don't You Want Me 25 The Communards Don't Leave Me This Way 26 Jackie Wilson Reet Petite 27 Paul Hardcastle 19 28 Irene Cara Fame 29 Berlin Take My Breath Away 30 Madonna Into The Groove 31 The Bangles Eternal Flame 32 Renee & Renato Save Your Love 33 Black Lace Agadoo 34 Chaka Khan I Feel For You 35 Diana Ross Chain Reaction 36 Shakin' Stevens This Ole House 37 Adam & The Ants Stand And Deliver 38 UB40 Red Red Wine 1980’S Top 100 Tracks Page 3 of 31 39 Boris Gardiner I Want To Wake Up With You 40 Soul II Soul Back To Life 41 Whitney Houston Saving All My Love For You 42 Billy Ocean When The Going -

Gowland, Ben (2021) the Decolonial Spatial Politics of West Indian Black Power: Praxis, Theory and Transnational Exchange

Gowland, Ben (2021) The decolonial spatial politics of West Indian black power: praxis, theory and transnational exchange. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/82297/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Decolonial Spatial Politics of West Indian Black Power: Praxis, Theory and Transnational Exchange Ben Gowland Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) School of Geographical and Earth Sciences College of Science and Engineering University of Glasgow Abstract The 1960s and 1970s were tumultuous decades in the West Indies. In this period, many of the islands of this former British colony attained formal independence and with this national identity, international alignment, state and economic structure and national trajectory become objects of political contestation for the first time in fully free and democratic nation-states. It was in this field of social, political and cultural upheaval that a significant Black Power movement and ideology emerged in the later years of the 1960s. Emergent from growing popular dissatisfaction with the trajectories and construction of these newly independent states and rooted in longstanding and powerful currents of subaltern race consciousness and anti-colonial and anti-imperial resistance the West Indian Black Power movement represented a serious challenge to the region’s post-colonial states and governments.