Robert Adam's Engagement with Medieval Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lambertville Design Guidelines

Lambertville Design Guidelines September 2, 2009 Draft Lambertville Design Guidelines City of Lambertville Hunterdon County, NJ September 2, 2009 Lambertville City Council Prepared by Mosaic Planning and Design, LLC Hon. David M. DelVecchio, Mayor Linda Weber, PP, AICP Steven M. Stegman, Council President Beth Asaro Ronald Pittore With Assistance From Clarke Caton Hintz Wardell Sanders Geoffrey Vaughn, ASLA Lambertville Planning Board Brent Krasner, PP, AICP Timothy Korzun, Chairman This plan was funded by a generous grant from the Paul Kuhl, Vice-Chairman Office of Smart Growth in the Department of Com- Acknowledgements Hon. David M. Delvecchio, Mayor munity Affairs. Hon. Ronald Pittore, Councilman Paul A. Cronce Beth Ann Gardiner Jackie Middleton John Miller Emily Goldman Derek Roseman, alternate David Morgan, alternate Crystal Lawton, Board Secretary William Shurts, Board Attorney Robert Clerico, PE, Board Engineer Linda B. Weber, AICP/PP, Board Planner Lambertville Historic Commission John Henchek, Chairman James Amon Richard Freedman Stewart Palilonis Sara Scully Lou Toboz 1. Introduction .......................................................................................1 5.3 Street Corridor Design ......................................................17 5.3.1 Sidewalks & Curbs ...................................................................17 2. Overview of Lambertville .............................................................3 5.3.2 Street Crossings ........................................................................17 -

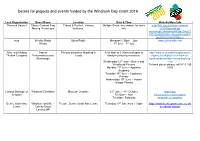

Details for Projects and Events Funded by the Windrush Day Grant 2019

Details for projects and events funded by the Windrush Day Grant 2019 Lead Organisation Event Name Location Date & Time Website/More info Thurrock Council Tilbury Carnival Flag Tilbury & Purfleet. Various Multiple Dates, see website for more http://tott.org.uk/tilbury-carnival- Making Workshops locations. info 2019-flag-making- workshops/?fbclid=IwAR3tpeSAxCV PIZYZpIZkiRo8Fn_FkvvjB8Js4dSrC ppuZN3C01HiOTObr_s. acta Weekly Radio Ujima Radio Mondays 1.30pm – 2pm www.ujimaradio.com Shows 3rd June – 1st July Alive and Kicking Drama Primary schools in Bradford & All to start at 9.30am and open to http://www.aliveandkickingtheatreco Theatre Company Performances and Leeds family/community members: mpany.co.uk/project/eh-kwik-eh- Workshops kwak-windrush-day-events-booking- Wednesday 12th June – Burley and now Woodhead Primary To book places please call 0113 295 Monday 17th June – Appleton 8190 Academy Tuesday 18th June – Copthorne Primary Wednesday 19th June – Horton Grange Primary London Borough of Windrush Exhibition Museum Croydon 12th June – 31st October https://jus- Croydon 10.30am – 4pm tickets.com/events/croydon- Tuesday - Saturday windrush-celebration/ Bernie Grant Arts Windrush and Me - Theatre, Bernie Grant Arts Centre Thursday 13th June from 7.30pm https://www.berniegrantcentre.co.uk/ Centre Talk by David see/david-lammy/ Lammy MP Details for projects and events funded by the Windrush Day Grant 2019 Bernie Grant Arts Pool of London Film Theatre, Bernie Grant Arts Centre Thursday 13th June from 7.00pm https://www.berniegrantcentre.co.uk/ Centre Screening see/film-pool-of-london-1951/ Bernie Grant Arts Rudeboy Film Theatre, Bernie Grant Arts Centre Saturday 15th & 21st June – 7pm https://www.berniegrantcentre.co.uk/ Centre Screening see/film-rudeboy/ London Borough of Windrush Highgate Library, Hornsey Library, 15th – 22nd June During library https://www.haringey.gov.uk/sites/ha Haringey Generation Displays St. -

London National Park City Week 2018

London National Park City Week 2018 Saturday 21 July – Sunday 29 July www.london.gov.uk/national-park-city-week Share your experiences using #NationalParkCity SATURDAY JULY 21 All day events InspiralLondon DayNight Trail Relay, 12 am – 12am Theme: Arts in Parks Meet at Kings Cross Square - Spindle Sculpture by Henry Moore - Start of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail, N1C 4DE (at midnight or join us along the route) Come and experience London as a National Park City day and night at this relay walk of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail. Join a team of artists and inspirallers as they walk non-stop for 48 hours to cover the first six parts of this 36- section walk. There are designated points where you can pick up the trail, with walks from one mile to eight miles plus. Visit InspiralLondon to find out more. The Crofton Park Railway Garden Sensory-Learning Themed Garden, 10am- 5:30pm Theme: Look & learn Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, SE4 1AZ The railway garden opens its doors to showcase its plans for creating a 'sensory-learning' themed garden. Drop in at any time on the day to explore the garden, the landscaping plans, the various stalls or join one of the workshops. Free event, just turn up. Find out more on Crofton Park Railway Garden Brockley Tree Peaks Trail, 10am - 5:30pm Theme: Day walk & talk Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, London, SE4 1AZ Collect your map and discount voucher before heading off to explore the wider Brockley area along a five-mile circular walk. The route will take you through the valley of the River Ravensbourne at Ladywell Fields and to the peaks of Blythe Hill Fields, Hilly Fields, One Tree Hill for the best views across London! You’ll find loads of great places to enjoy food and drink along the way and independent shops to explore (with some offering ten per cent for visitors on the day with your voucher). -

Pentagons in Medieval Architecture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Építés – Építészettudomány 46 (3–4) 291–318 DOI: 10.1556/096.2018.008 PENTAGONS IN MEDIEVAL ARCHITECTURE KRISZTINA FEHÉR* – BALÁZS HALMOS** – BRIGITTA SZILÁGYI*** *PhD student. Department of History of Architecture and Monument Preservation, BUTE K II. 82, Műegyetem rkp. 3, H-1111 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] **PhD, assistant professor. Department of History of Architecture and Monument Preservation, BUTE K II. 82, Műegyetem rkp. 3, H-1111 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] ***PhD, associate professor. Department of Geometry, BUTE H. II. 22, Egry József u. 1, H-1111 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] Among regular polygons, the pentagon is considered to be barely used in medieval architectural compositions, due to its odd spatial appearance and difficult method of construction. The pentagon, representing the number five has a rich semantic role in Christian symbolism. Even though the proper way of construction was already invented in the Antiquity, there is no evidence of medieval architects having been aware of this knowledge. Contemporary sources only show approximative construction methods. In the Middle Ages the form has been used in architectural elements such as window traceries, towers and apses. As opposed to the general opinion supposing that this polygon has rarely been used, numerous examples bear record that its application can be considered as rather common. Our paper at- tempts to give an overview of the different methods architects could have used for regular pentagon construction during the Middle Ages, and the ways of applying the form. -

The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE)

ABSTRACT MARY ELIZABETH BLUME The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE) The Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century in Europe aroused a debate concerning the origin of a style already six centuries old. Besides the underlying quandary of how to define or identify “Gothic” structures, the Victorian revivalists fought vehemently over the national birthright of the style. Although Gothic has been traditionally acknowledged as having French origins, English revivalists insisted on the autonomy of English Gothic as a distinct and independent style of architecture in origin and development. Surprisingly, nearly two centuries later, the debate over Gothic’s nationality persists, though the nationalistic tug-of-war has given way to the more scholarly contest to uncover the style’s authentic origins. Traditionally, scholarship took structural or formal approaches, which struggled to classify structures into rigidly defined periods of formal development. As the Gothic style did not develop in such a cleanly linear fashion, this practice of retrospective labeling took a second place to cultural approaches that consider the Gothic style as a material manifestation of an overarching conscious Gothic cultural movement. Nevertheless, scholars still frequently look to the Isle-de-France when discussing Gothic’s formal and cultural beginnings. Gothic historians have entered a period of reflection upon the field’s historiography, questioning methodological paradigms. This -

Landscape Sensitivity and Capacity Study August 2013

LANDSCAPE SENSITIVITY AND CAPACITY STUDY AUGUST 2013 Prepared for the Northumberland AONB Partnership By Bayou Bluenvironment with The Planning and Environment Studio Document Ref: 2012/18: Final Report: August 2013 Drafted by: Anthony Brown Checked by: Graham Bradford Authorised by: Anthony Brown 05.8.13 Bayou Bluenvironment Limited Cottage Lane Farm, Cottage Lane, Collingham, Newark, Nottinghamshire, NG23 7LJ Tel: +44(0)1636 555006 Mobile: +44(0)7866 587108 [email protected] The Planning and Environment Studio Ltd. 69 New Road, Wingerworth, Chesterfield, Derbyshire, S42 6UJ T: +44(0)1246 386555 Mobile: +44(0)7813 172453 [email protected] CONTENTS Page SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ i 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Objectives of the Study ........................................................................................ 2 Key Views Study ........................................................................................................................ 3 Consultation .............................................................................................................................. 3 Format of the Report ............................................................................................................... -

Y\5$ in History

THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A5 In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree Mi ST Master of Arts . Y\5$ In History by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California May, 2016 Copyright by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Gargoyles of San Francisco: Medievalist Architecture in Northern California 1900-1940 by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr., and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History at San Francisco State University. <2 . d. rbel Rodriguez, lessor of History Philip Dreyfus Professor of History THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California 2016 After the fire and earthquake of 1906, the reconstruction of San Francisco initiated a profusion of neo-Gothic churches, public buildings and residential architecture. This thesis examines the development from the novel perspective of medievalism—the study of the Middle Ages as an imaginative construct in western society after their actual demise. It offers a selection of the best known neo-Gothic artifacts in the city, describes the technological innovations which distinguish them from the medievalist architecture of the nineteenth century, and shows the motivation for their creation. The significance of the California Arts and Crafts movement is explained, and profiles are offered of the two leading medievalist architects of the period, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan. -

British Neoclassicism COMMONWEALTH of AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969

702132/702835 European Architecture B British Neoclassicism COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice authenticity reductionism NEOCLASSICISM sublimity neoclassicism ROMANTIC CLASSICISM innovation/radicalism ARCHAEOLOGYARCHAEOLOGY ARCHAEOLOGICAL PUBLICATIONS Robert Wood, Ruins of Palmyra,1753 Robert Wood, Ruins of Balbec,1757 J D Leroy, Les Ruines des plus Beaux Monuments de la Grèce, 1758 James Stuart & Nicholas Revett, Antiquities of Athens, I, 1762 James Stuart & Nicholas Revett, Antiquities of Athens, II, 1790 Robert Adam, Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia, 1764 Richard Chandler, Ionian Antiquities, I, 1769 Richard Chandler, Ionian Antiquities, II, 1797 Temple of Apollo, Stourhead, by Henry Flitcroft, 1765 the ‘Temple of Venus’ at Baalbek, c AD 273 George Mott & S S Aall, Follies and Pleasure Pavilions (London 1989), p 102; Robert Wood, The Ruins of Balbec, otherwise Heliopolis in Coelosyria (London 1757) THETHE SUBLIMESUBLIME 'The artist moved by the grandeur of giant statue of Ancient Ruins', by Henry Fuseli, 1778-9 Constantine, c 313 Toman, Neoclassicism, p 11 MUAS 12,600 Castel Sant' Angelo, Rome, -

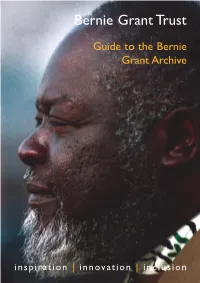

Guide to the Archive

Bernie Grant Trust Guide to the Bernie Grant Archive inspiration | innovation | inclusion Contents Compiled by Dr Lola Young OBE Bernie Grant – the People’s Champion . 4 Edited by Machel Bogues What’s in the Bernie Grant Archive? . 11 How it’s organised . 14 Index entries . 15 Tributes - 2000 . 16 What are Archives? . 17 Looking in the Archives . 17 Why Archives are Important . 18 What is the Value of the Bernie Grant Archive? . 18 How we set up the Bernie Grant Collection . 20 Thank you . 21 Related resources . 22 Useful terms . 24 About The Bernie Grant Trust . 26 Contacting the Bernie Grant Archive . 28 page | 3 Bernie Grant – the People’s Champion Born into a family of educationalists on London. The 4000 and overseas. He was 17 February 1944 in n 18 April 2000 people who attended a committed anti-racist Georgetown, Guyana, thousands of O the service at Alexandra activist who campaigned Bernie Grant was the people lined the streets Palace made this one of against apartheid South second of five children. of Haringey to follow the largest ever public Africa, against the A popular, sociable child the last journey of a tributes at a funeral of a victimisation of black at primary school, he charismatic political black person in Britain. people by the police won a scholarship to leader. Bernie Grant had in Britain and against St Stanislaus College, a been the Labour leader Bernie Grant gained racism in health services Jesuit boys’ secondary of Haringey Council a reputation for being and other public and school. Although he during the politically controversial because private institutions. -

Giving Our Past a Future Momentum

GIVING OUR PAST A FUTURE: THE WORK OF WORLD MONUMENTS FUND BRITAIN Foreword by Kevin McCloud, Ambassador, WMF Britain Pouring money into an old building is one of the great honourable activities of the modern age. How else are we supposed to understand where we’re going unless we understand where we’ve been? How else can we give any kind of context to our children’s education if we don’t care for what we have? World Monuments Fund Britain have to be congratulated for preserving so many exceptional sites for future generations and for helping them to make that vital connection with their sense of place, community and history. Front cover: A restored Corinthian capital at Stowe House in Buckinghamshire. Inside covers: The restored Large Library ceiling at Stowe House. GIVING OUR PAST A FUTURE: THE WORK OF WORLD MONUMENTS FUND BRITAIN Gorton Monastery, Manchester. This fine, derelict Victorian building by E.W. Pugin was Watch listed in 1998 and 2000. Subsequent WMF funding enabled the Trust to work up detailed plans for the rescue of the site when no other sources of funding were available. Bonnie Burnham Jonathan Foyle President, World Monuments Fund CEO,World Monuments Fund Britain Great works of architecture deserve to be World Monuments Fund exists to provide a celebrated beyond the time of their network of expert, considered and creation, and as their histories accumulate substantive responses to the needs of new chapters, these should add to our important but ailing historic sites around the appreciation and enjoyment of the place. world. WMF Britain does not dispense grants This principle has guided the work of from an endowment, but raises specific funds World Monuments Fund since its founding from scratch. -

News Update for London's Museums

@LondonMusDev E-update for London’s Museums – 09 November 2020 The 4 week long national lockdown began on Thursday 05 November, meaning museums and galleries should now be closed in line with government guidance until at least Wednesday 02 December. It has been announced that some heritage locations can still be visited if they are outside – provided current social distancing rules are observed. You can find further information about that on the Gov.uk website. You can get an overview of all of the new national restrictions on the gov.uk website. We strongly advise that you continue to follow the news and government announcements, as they happen, over the coming days and weeks. Last week the government announced further extensions to the furlough scheme, to March 2021. The government will extend furlough payments at the original 80%, up to a maximum of £2,500 per employee. Employers will only need to cover pension and National Insurance contributions during the month of November, but can top up the remaining 20% of their staff salaries if they wish. To be eligible for this extension, employees must have been on the payroll by 30 October 2020, but they do not need to have been furloughed before that date. Workers who were made redundant in advance of the planned end of the furlough scheme on 31 October can be rehired under the current furlough extension. The relevant section is 2.4 in the policy paper which can be found here. The government has also announced that businesses required to close in England due to local or national restrictions will be eligible for Business Grants of up to £3,000 per month, dependent on their rateable value. -

5352 List of Venues

tradername premisesaddress1 premisesaddress2 premisesaddress3 premisesaddress4 premisesaddressC premisesaddress5Wmhfilm Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Brampton Cumbria CA8 7BH Films Capheaton Hall Capheaton Hall Capheaton Newcastle upon Tyne NE19 2AB Films Prudhoe Castle Prudhoe Castle Station Road Prudhoe Northumberland NE42 6NA Films Stonehaugh Social Club Stonehaugh Social Club Community Village Hall Kern Green Stonehaugh NE48 3DZ Films Duke Of Wellington Duke Of Wellington Newton Northumberland NE43 7UL Films Alnwick, Westfield Park Community Centre Westfield Park Park Road Longhoughton Northumberland NE66 3JH Films Charlie's Cashmere Golden Square Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland TD15 1BG Films Roseden Restaurant Roseden Farm Wooperton Alnwick NE66 4XU Films Berwick upon Lowick Village Hall Main Street Lowick Tweed TD15 2UA Films Scremerston First School Scremerston First School Cheviot Terrace Scremerston Northumberland TD15 2RB Films Holy Island Village Hall Palace House 11 St Cuthberts Square Holy Island Northumberland TD15 2SW Films Wooler Golf Club Dod Law Doddington Wooler NE71 6AW Films Riverside Club Riverside Caravan Park Brewery Road Wooler NE71 6QG Films Angel Inn Angel Inn 4 High Street Wooler Northumberland NE71 6BY Films Belford Community Club Memorial Hall West Street Belford NE70 7QE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Magdalene Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed TD14 1NE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Berwick Holiday Centre Magdalen Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland