A Case Study Analysis of Poverty Coverage in Rural Appalachian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

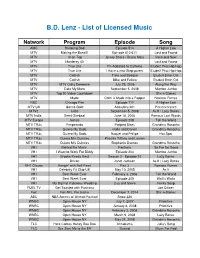

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 2 Live Crew Sports Weekend 2nd II None If You Want It 2nd II None Classic 220 2Pac Changes 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac I Get Around / Keep Ya Head Up 50 Cent Candy Shop 702. Where My Girls At 7L & Esoteric The Soul Purpose A Taste Of Honey A Taste Of Honey A Tribe Called Quest Unreleased & Unleashed Above The Law Untouchable Abyssinians Best Of The Abyssinians Abyssinians Satta Adele 21. Adele 21. Admiral Bailey Punanny ADOR Let It All Hang Out African Brothers Hold Tight (colorido) Afrika Bambaataa Renegades Of Funk Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Agallah You Already Know Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Akon Konvicted Akrobatik The EP Akrobatik Absolute Value Al B. Sure Rescue Me Al Green Greatest Hits Al Johnson Back For More Alexander O´Neal Criticize Alicia Keys Fallin Remix Alicia Keys As I Am (vinil colorido) Alicia Keys A Woman´s Worth Alicia Myers You Get The Best From Me Aloe Blacc Good Things Aloe Blacc I Need A Dollar Alpha Blondy Cocody Rock Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (vinil colorido) Alton Ellis Mad Mad Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Anita Baker Rapture Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Augustus Pablo King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown Augustus Pablo In Fine Style Augustus Pablo This Is Augustus Pablo Augustus Pablo Dubbing With The Don Augustus Pablo Skanking Easy AZ Sugar Hill B.G. -

Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 Paul L. Robertson Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Appalachian Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons © Paul L. Robertson Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5854 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robertson i © Paul L. Robertson 2019 All Rights Reserved. Robertson ii The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. By Paul Lester Robertson Bachelor of Arts in English, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2000 Master of Arts in Appalachian Studies, Appalachian State University, 2004 Master of Arts in English, Appalachian State University, 2010 Director: David Golumbia Associate Professor, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2019 Robertson iii Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank his loving wife A. Simms Toomey for her unwavering support, patience, and wisdom throughout this process. I would also like to thank the members of my committee: Dr. David Golumbia, Dr. -

Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash Ashley F

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 12-14-2015 Redneckaissance: Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash Ashley F. Miller University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Miller, A. F.(2015). Redneckaissance: Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3217 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REDNECKAISSANCE: HONEY BOO BOO, TUMBLR, AND THE STEREOTYPE OF POOR WHITE TRASH by Ashley F. Miller Bachelor of Arts Emory University, 2006 Master of Fine Arts Florida State University, 2008 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mass Communications College of Information and Communications University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: August Grant, Major Professor Carol Pardun, Committee Member Leigh Moscowitz, Committee Member Lynn Weber, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Ashley F. Miller, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgements Although her name is not among the committee members, this study owes a great deal to the extensive help of Kathy Forde. It could not have been done without her. Thanks go to my mother and fiancé for helping me survive the process, and special thanks go to L. Nicol Cabe for ensuring my inescapable relationship with the Internet and pop culture. -

The Consequences of Appalachian Representation in Pop Culture

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--English English 2017 STRANGERS WITH CAMERAS: THE CONSEQUENCES OF APPALACHIAN REPRESENTATION IN POP CULTURE Chelsea L. Brislin University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.252 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brislin, Chelsea L., "STRANGERS WITH CAMERAS: THE CONSEQUENCES OF APPALACHIAN REPRESENTATION IN POP CULTURE" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--English. 59. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/english_etds/59 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--English by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

NSR 006 CELPH TITLED & BUCKWILD Nineteen Ninety Now CD

01. The Deal Maker 02. Out To Lunch (feat. Treach of Naughty By Nature) 03. Eraserheads (feat. Vinnie Paz of Jedi Mind Tricks) 04. F*ckmaster Sex 05. Swashbuckling (feat. Apathy, Ryu & Esoteric) 06. I Could Write A Rhyme 07. Hardcore Data 08. Mad Ammo (feat. F.T. & R.A. The Rugged Man) 09. Tingin' 10. There Will Be Blood (feat. Sadat X, Grand Puba, A.G., O.C. & Diamond) 11. Miss Those Days 12. Step Correctly 13. Wack Juice 14. Styles Ain't Raw (feat. Apathy & Chino XL) 15. Where I Are 16. Time Travels On (feat. Majik Most & Dutchmassive) Nineteen Ninety Now is finally here and a Hip Hop renaissance is about to begin! The art form is brought KEY SELLING POINTS: full-circle through this groundbreaking collaboration • Long awaited debut album from Celph Titled, who between underground giant Celph Titled and production already has gained a huge underground following as a legend Buckwild of D.I.T.C. fame! Showing that the core member of Jedi Mind Tricks' Army of the Pharaohs crew and his own trademark Demigodz releases. Also lessons from the past can be combined with the as a part of Mike Shinoda's Fort Minor project and tour, innovations of the present, these two heavyweight his fanbase has continued to grow exponentially artists have joined forces to create a neo-classic. By • Multi-platinum producer Buckwild from the legendary Diggin’ In The Crates crew (D.I.T.C.) has produced having uninhibited access to Buckwild’s original mid-90s countless classics over the last two decades for artists production, Celph Titled was able to select and record ranging from Artifacts, Organized Konfusion, and Mic to over 16 unreleased D.I.T.C. -

Bridging the Digital Divide in Rural Appalachia: Internet Usage in the Mountains Jacob J

Informing Science InSITE - “Where Parallels Intersect” June 2003 Bridging the Digital Divide in Rural Appalachia: Internet Usage in the Mountains Jacob J. Podber, Ph.D. Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, USA [email protected] Abstract This project looks at Internet usage within the Melungeon community of Appalachia. Although much has been written on the coal mining communities of Appalachia and on ethnicity within the region, there has been little written on electronic media usage by Appalachian communities, most notably the Melun- geons. The Melungeons are a group who settled in the Appalachian Mountains as early as 1492, of apparent Mediterranean descent. Considered by some to be tri-racial isolates, to a certain extent, Melungeons have been culturally constructed, and largely self-identified. According to the founder of a popular Me- lungeon Web site, the Internet has proven an effective tool in uncovering some of the mysteries and folklore surrounding the Melungeon community. This Web site receives more than 21,000 hits a month from Melungeons or others interested in the group. The Melungeon community, triggered by recent books, films, and video documentaries, has begun to use the Internet to trace their genealogy. Through the use of oral history interviews, this study examines how Melungeons in Appalachia use the Internet to connect to others within their community and to the world at large. Keywords : Internet, media, digital divide, Appalachia, rural, oral history, ethnography, sociology, com- munity Introduction In Rod Carveth and Susan Kretchmer’s paper “The Digital Divide in Western Europe,” (presented at the 2002 International Summer Conference on Communication and Technology) the authors examined how age, income and gender were predictors of the digital divide in Western Europe. -

A History of Appalachia

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Appalachian Studies Arts and Humanities 2-28-2001 A History of Appalachia Richard B. Drake Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Drake, Richard B., "A History of Appalachia" (2001). Appalachian Studies. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/23 R IC H ARD B . D RA K E A History of Appalachia A of History Appalachia RICHARD B. DRAKE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by grants from the E.O. Robinson Mountain Fund and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2001 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2003 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kenhlcky Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 12 11 10 09 08 8 7 6 5 4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drake, Richard B., 1925- A history of Appalachia / Richard B. -

Trust Mechanisms, Cultural Difference and Poverty Alleviation

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 20 (2018) Issue 2 Article 8 Trust Mechanisms, Cultural Difference and Poverty Alleviation Lihua Guo MinZu University of China Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Economics Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Guo, Lihua. "Trust Mechanisms, Cultural Difference and Poverty Alleviation." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 20.2 (2018): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.3229> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 106 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of February 10Th and February 17Th (As of 2.3.14)

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of February 10th and February 17th (as of 2.3.14) Below please find program highlights for TLC’s primetime schedule for the weeks of February 10th and 17th. There are preview episodes and episodic photography available for select programs/episodes on press.discovery.com. Please check with us for further information. TLC PRESS CONTACT: Jordyn Linsk: 240-662-2421 [email protected] TH WEEK OF FEBRUARY 10 (as of 2.3.14) OF NOTE THIS WEEK: Special Premieres SAY YES TO THE DRESS: THE BIG DAY – Friday, February 14 UNTOLD STORIES OF THE ER: SEX EDITION – Saturday, February 15 MONDAY, FEBRUARY 10 9:00PM ET/PT CAKE BOSS – “BICEPS AND BIRTHDAYS” Buddy rolls up his sleeves and shows off his muscles when he must make a cake for a family of professional arm wrestlers. And Mauro and his kids plan a surprise romantic birthday celebration for Madeline inside the bakery. TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 11 9:00PM ET/PT MY 600-LB. LIFE – “PAULA’S STORY” Paula has had a tough life, and at over 600lbs, has built a physical wall around herself to push people away. When she suddenly loses someone she loves, Paula can no longer ignore the threat of losing her own life – especially for her children’s sake. WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 12 9:00PM ET/PT HOARDING: BURIED ALIVE – “A VCR FOR EVERY DAY OF THE WEEK” John and Joe are a father and son duo who both hoard. Their home—which has no functional bedroom or usable kitchen—is packed to the ceiling with items the pair has relentlessly accumulated over the past decade. -

“A People Who Have Not the Pride to Record Their History Will Not Long

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE i “A people who have not the pride to record their History will not long have virtues to make History worth recording; and Introduction no people who At the rear of Old Main at Bethany College, the sun shines through are indifferent an arcade. This passageway is filled with students today, just as it was more than a hundred years ago, as shown in a c.1885 photograph. to their past During my several visits to this college, I have lingered here enjoying the light and the student activity. It reminds me that we are part of the past need hope to as well as today. People can connect to historic resources through their make their character and setting as well as the stories they tell and the memories they make. future great.” The National Register of Historic Places recognizes historic re- sources such as Old Main. In 2000, the State Historic Preservation Office Virgil A. Lewis, first published Historic West Virginia which provided brief descriptions noted historian of our state’s National Register listings. This second edition adds approx- Mason County, imately 265 new listings, including the Huntington home of Civil Rights West Virginia activist Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the New River Gorge Bridge, Camp Caesar in Webster County, Fort Mill Ridge in Hampshire County, the Ananias Pitsenbarger Farm in Pendleton County and the Nuttallburg Coal Mining Complex in Fayette County. Each reveals the richness of our past and celebrates the stories and accomplishments of our citizens. I hope you enjoy and learn from Historic West Virginia. -

Poverty-Related Topics Found in Dissertations: a Bibliography. INS1ITUTION Wisconsin Univ., Madison

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 135 540 RC 009 699 AUTEJOR O'Neill, Mara, Comp.; And Others TITLE Poverty-Related Topics Found in Dissertations: A Bibliography. INS1ITUTION Wisconsin Univ., Madison. Inst. for Research on Poverty. PUB LATE 76 NOTE 77p. EDRS PRICE 1E-$0.83 HC-$4.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indians; *Annotated Bibliographies; Attitudes; Bilingual Education; Community Involvement; Culturally Disadvantaged; *Doctoral Theses; *Economically Disadvantaged; *Economic Disadvantagement; *Economic Research; Government Role; Guaranteed Income; Human Services; Low Income Groups; Manpower Development; Mexican Americans; Negroes; Clder Adults; Politics; Poverty Programs; Dural Population; Social Services; *Socioeconomic Influences; Welfare; Working Women IDENTIFIERS Chicanos ABSIRACI Arranged alphabetically by main toPic, this bibliography cites 322 doctoral dissertations, written between 1970 and 1974, pertaining to various aspects of poverty. Where possible, annotations have been written to present the kernel idea of the work. Im many instances, additional subject headings which reflect important secondary thrusts are also included. Topics covered include: rural poverty; acceso and delivery of services (i.e., food, health, medical, social, and family planning services); employment; health care; legal services; public welfare; adoptions, transracial; the aged; anomie; antipoverty programs; attitudes of Blacks, Congressmen, minorities, residents, retailers, and the poor; bilingual-bicultural education; discrimination dn employment and housing; social services; social welfare; Blacks, Chicanos, and Puerto Ricans; participation of poor in decision making; poverty in history; education; community participation; culture of poverty; and attitudes toward fertility, social services, welfare, and the poor. Author and zubject indices are included to facilitate the location of a work. The dicsertations are available at the institutions wherethe degrees were earned or from University Microfilms.