Constitutional Reasoning in Europe. a Linguistic Turn in Comparative Constitutional Law Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Plan Pompeu Fabra University

Presentation from the rector Strategic Plan Pompeu Fabra University 2016 2025 3 Strategic Plan 2016-2025 2 Contents Presentation from the rector, 4 The UPF Strategic Plan, 8 Mission, vision and values, 14 Cross-cutting themes, 20 Strategic areas, 24 UPF in figures, 56 Strategic Plan 2016-2025 4 Presentation from the rector To orient oneself again profound aspects of Kantian thought: subjectivity is not only not opposed to universal validity, but In his essay What Does it Mean to Orient Oneself rather the most basic condition for its possibility. in Thinking, Kant has to resort to the metaphor of We might not agree on what a strategic plan is all the cardinal points to try to explain that, despite about, but we can try to see if we each share a set their universality, the principles of thinking are of principles that can form the basis for orienting essential subjective principles. “... and if someone Pompeu Fabra University, in the same way that as a joke had moved all the objects around so we all know which is our right side and which that what was previously on the right was now on is our left, even if it brings us back to a purely the left, I would be quite unable to find anything subjective feeling. in a room whose walls were otherwise wholly identical. But I can soon orient myself through Before attempting to address what I think a the mere feeling of a difference between my two strategic plan for this university should consist sides, my right and my left”. -

Cv Cantore.Pdf

Cristiano Cantore Research Hub E-mail: [email protected] Bank of England E-mail: [email protected] Threadneedle Street Web: http://www.cristianocantore.com London EC2R 8AH Phone: +44 (0)2034614469 Fields of Business Cycle Theory, Monetary and Fiscal Policy, Applied Macroeconomics Interest Current Research Advisor, Research Hub, Bank of England. 07/2021 to date Employment Reader in Economics (Part-Time), University of Surrey, Guildford. 08/2018 to date Other Centre for Macroeconomics (LSE), Euro Area Business Cycle Network, Central Bank Affiliations Research Association and Centre for International Macroeconomics (Surrey). Education Ph.D. in Economics University of Kent, (passed without corrections). 2011 Dissertation Examiners: Prof. M. Ellison (Oxford), Dr. K.Shibayama (Kent). M.Sc. in Economics, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona. 2005 B.A. in Economics and Statistics, L. Bocconi University, Milan. 2004 Previous Senior Research Economist, Research Hub, Bank of England. 09/2018 to 06/2021 Positions Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Surrey, Guildford. 04/2013 to 07/2018 Visiting Professor, University of California San Diego. 02/2014 to 07/2014 Visiting Research Fellow, Banco de España, Madrid. 04/2012 to 08/2012 Lecturer in Economics, University of Surrey, Guildford. 09/2009 to 03/2013 Visiting Professor, University of Cagliari. 01/2012 to 02/2012 Intern, European Central Bank, Economics DG. 08/2008 to 10/2008 Intern, OECD, Economic Department, Country desk 1. 07/2007 to 09/2007 Publications (2021) Workers, Capitalists, and the Government: Fiscal Policy and Income (Re)Distribution, joint with Lukas Freund (University of Cambridge). Journal of Monetary Economics, 119, 58-74. -

International Partners

BOSTON COLLEGE OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS International Partners Boston College maintains bilateral agreements for student exchanges with over fifty of the most prestigious universities worldwide. Each year the Office of International Programs welcomes more than 125 international exchange students from our partner institutions in approximately 30 countries. We are proud to have formal exchange agreements with the following universities: AFRICA Morocco Al Akhawayn University South Africa Rhodes University University of Cape Town ASIA Hong Kong Hong Kong University of Science and Techonology Japan Sophia University Waseda University Korea Sogang University Philippines Manila University AUSTRALIA Australia Monash University Murdoch University University of New South Wales University of Notre Dame University of Melbourne CENTRAL & SOUTH AMERICA Argentina Universidad Torcuato di Tella Universidad Catolica de Argentina Brazil Pontificia Universidad Católica - Rio Chile Pontificia Universidad Católica - Chile Universidad Alberto Hurtado Ecuador Universidad San Francisco de Quito HOVEY HOUSE, 140 COMMONWEALTH AVENUE, CHESTNUT HILL, MASSACHUSETTS 02467-3926 TEL: 617-552-3827 FAX: 617-552-0647 1 Mexico Iberoamericana EUROPE Bulgaria University of Veliko-Turnovo Denmark Copenhagen Business School University of Copenhagen G.B-England Lancaster University Royal Holloway University of Liverpool G.B-Scotland University of Glasgow France Institut Catholique de Paris Mission Interuniversitaire de Coordination des Echanges Franco-Americains – Paris -

July 2016 DANIEL PARAVISINI London School of Economics

July 2016 DANIEL PARAVISINI London School of Economics Phone: +44 020 7107 5371 Houghton Street, OLD M3.10 E-mail: [email protected] London WC2 A2AE United Kingdom EDUCATION Ph. D., Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge MA, U.SA., 2005. M.B.A., Instituto de Estudios Superiores de Administración (IESA), Caracas, Venezuela. 1997. B.S. Cum Laude, Mechanical Engineering, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Caracas, Venezuela. 1994. ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2016 – Professor, London School of Economics and Social Sciences, London, U.K. 2011 – 2016 Associate Professor, London School of Economics and Social Sciences, London, U.K. 2011 – 2012 G. Winnick and M. Granoff Associate Professor of Business, Columbia University GSB, New York, U.S.A. 2009 – 2011 Associate Professor of Finance, Columbia University GSB, New York, U.S.A. 2005 – 2009 Assistant Professor of Finance, Columbia University GSB, New York, U.S.A. 1997 – 1999 Researcher/Lecturer, IESA, Public Policy Department, Caracas, Venezuela PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS AND ACTIVITIES Affiliations Bureau for Research and Economic Analysis of Development, Junior Affiliate Centre for Economic Policy Research, Research Affiliate Financial Markets Group Research Center – LSE, Research Affiliate Innovations for Poverty Action, SME Initiative, Affiliate International Growth Centre, LSE, Affiliate National Bureau of Economic Research, Faculty Research Fellow (2011 - 2014) Co-Editor Journal of Law, Economics and Organization (2014 - ) Associate Editor Journal of Finance (2012 - ) Journal of -

International Seminar on European Legal and Political Studies / Séminaire International D'études Juridiques Et Politiques Eu

UNIVERSITÉ PARIS 1 PANTHÉON- SORBONNE UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID COLEGIO DE ALTOS ESTUDIOS EUROPEOS MIGUEL SERVET, PARÍS International Seminar on European Legal and Political Studies / Séminaire International d’études juridiques et politiques européennes Pantheon-Sorbonne University Paris 1 3-8 July 2017 Intensive high-level international course on legal and socio-political matters which has been particularly thought for those wishing to deepen their knowledge of European integration towards the development of a diplomatic career or who are interested in working for intergovernmental organizations, law firms, departments of international companies, etc 30 hours (3 ECTS) (July 3-7,2017) Classes in the English language will be given to a reduced group of students at the Pantheon-Sorbonne University Paris 1. Limited places: they will be assigned by pre-registration order. The applicants will receive a payment instructions form. A joint certificate from the Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University and the Complutense University of Madrid will be given to students at the end of the course. The course is coordinated by: Miguel Servet College of Higher European Studies. Fees: Registration fees + lodging expenses at the Cité Universitaire of Paris (http://www.ciup.fr/) :1500 € Registration fees only: 800 €. Scholarships: two fee grants will be available for the students with the best records. CO-TAUGHT BY FACULTY FROM: Pantheon-Sorbonne University Paris 1 Complutense University of Madrid Carlos III University of Madrid Pompeu Fabra University of Barcelone CEU San Pablo University of Madrid University of Valencia PRE-REGISTRATIONS From April 25th to May10th 2017 Please, send an e-mail indicating interest to Prof. -

2 Phd Positions for Marie Sklodowska-Curie European Training Network on Explaining Global India

2 PhD positions for Marie Sklodowska-Curie European Training Network on explaining global India Call for 2 PhD students (Early Stage Researchers) to develop the PhD at the Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals (IBEI) in collaboration with the Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, involved in the Marie S. Curie European Training Network project H2020- MSCA-ITN-ETN-2016 “Explaining Global India: a multi-sectoral PhD training programme analysing the emergence of India as a global actor” (Global India). The Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals (IBEI) invites applications for Early Stage Researcher (ESR) positions in the Marie S. Curie European Training Network Global India. The successful candidates will be employed by IBEI and will enrol on a PhD training programme as a mandatory requirement. One of the candidates will enrol in the Universitat Pompeu Fabra PhD programme under the supervision of Prof. Jacint Jordana. The other one will enrol in the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona PhD programme under the supervision of the Prof. Esther Barbé. The Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals is a graduate teaching and research institution created by five universities in Barcelona (the University of Barcelona, the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Pompeu Fabra University, the Open University of Catalonia, and the Technical University of Catalonia). It supports research in the fields of international political economy, international relations, international security, foreign policy and comparative politics. IBEI is an equal opportunities employer. Further information about IBEI and its Master’s programmes can be obtained at http://www.ibei.org Explaining Global India: a multi-sectoral PhD training programme analysing the emergence of India as a global actor (Global India) The GLOBAL INDIA ETN will deliver a world-class multi-sectoral doctoral training programme focused on India’s emergence as a global and regional power, and its relationship with the EU. -

Veronica Benet

1 Curriculum Vitae Verónica Benet-Martínez Department of Social & Political Sciences Universitat Pompeu Fabra Ramon Trias Fargas 25-27 08005 Barcelona, Spain E-mail: [email protected] Office: +34 93 5422684 http://www.icrea.cat/Web/ScientificStaff/Veronica-Benet-Martinez-518 http://www.upf.edu/pdi/benet-martinez/en/prof/ Education 1995 Ph.D. in Social/Personality Psychology, University of California at Davis (UCD) 1989 B.S. in Psychology, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) Employment 2010-present ICREA1 Professor, Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) Department of Political and Social Sciences 2005-2010 Associate Professor of Psychology, University of California at Riverside (UCR) Social-Personality Psychology Area 2003-2005 Assistant Professor of Psychology, University of California at Riverside Social-Personality Psychology Area 1998-2002 Assistant Professor of Psychology, University of Michigan (UM) Personality Area (other affiliations: Social Area; Culture and Cognition program) 1995-1997 Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of California at Berkeley (UCB) Institute of Personality and Social Psychology Research Visiting appointments: University of California at Davis (Winter & Spring 2003): University of Barcelona (Summer 2008, 2009); UCR Center for Ideas and Society (Winter 2007) Research Interests Using correlational and experimental research designs, I examine the following issues: Multi/Bicultural identity: Psychological dynamics, correlates, and outcomes of managing two or more cultural orientations and identities; Individual -

Veronica Benet

Curriculum Vitae 08/12/2016 Verónica Benet-Martínez Department of Social & Political Sciences ║Universitat Pompeu Fabra Ramon Trias Fargas 25-27 ║08005 Barcelona, Spain E-mail: [email protected] Office: +34 93 5422684 Education 1995 Ph.D. in Social/Personality Psychology, University of California at Davis (UCD) 1989 B.S. in Psychology, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) Employment 2010-present ICREA1 Professor, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF) Department of Social and Political Sciences 2016 Distinguished Visiting Fellow, CUNY Graduate Center Advanced research Collaborative (cluster: Immigration) 2005-2010 Associate Professor of Psychology, University of California at Riverside (UCR) Social-Personality Psychology Area 2003-2005 Assistant Professor of Psychology, University of California at Riverside Social-Personality Psychology Area 2003 Visiting Professor, University of California at Davis Social-Personality Psychology Area 1998-2002 Assistant Professor of Psychology, University of Michigan (UM) Personality Area (other affiliations: Social Area; Culture and Cognition program) 1995-1997 Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of California at Berkeley (UCB) Institute of Personality and Social Psychology Research Other Invited Visiting Appointments: Columbia University (Spring 2014); University of California at Davis (Summer 2014); University of Barcelona (Summer 2009); UCR Center for Ideas and Society (Winter 2007) Research Interests Multi/Bicultural identity: Personality and socio-cognitive dynamics of managing two or more cultural -

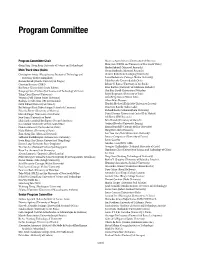

Program Committee

Program Committee Program Committee Chair Mauricio Ayala-Rincón (Universidade de Brasilia) Qiang Yang (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology) Haris Aziz (NICTA and University of New South Wales) Moshe Babaioff (Microso Research) Main Track Area Chairs Yoram Bachrach (Microso Research) Christopher Amato (Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Christer Bäckström (Linköping University) University of New Hampshire) Laura Barbulescu (Carnegie Mellon University) Roman Bartak (Charles University in Prague) Pablo Barcelo (Universidad de Chile) Christian Bessiere (CNRS) Leliane N. Barros (University of Sao Paulo) Blai Bonet (Universidad Simón Bolívar) Peter Bartlett (University of California, Berkeley) Xiaoping Chen (University of Science and Technology of China) Shai Ben-David (University of Waterloo) Yiling Chen (Harvard University) Ralph Bergmann (University of Trier) Veronica Dahl (Simon Fraser University) Alina Beygelzimer (Yahoo! Labs) Rodrigo de Salvo Braz (SRI International) Albert Bifet (Huawei) Edith Elkind (University of Oxford) Hendrik Blockeel (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) Boi Faltings (Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne) Francesco Bonchi (Yahoo Labs) Eduardo Ferme (University of Madeira) Richard Booth (Mahasarakham University) Marcelo Finger (University of Sao Paulo) Daniel Borrajo (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid) Joao Gama (University of Porto) Adi Botea (IBM Research) Lluis Godo (Artificial Intelligence Research Institute) Felix Brandt (University of Munich) Jose Guivant (University of New South Wales) Gerhard -

Utopias and Dystopias All Sessio

CES Virtual 27th International Conference of Europeanists Europe’s Past, Present, and Future: Utopias and Dystopias All sessions are listed in Eastern Daylight Time (EDT). June 2, 2021 1 Pre-Conference Side Events MONDAY, JUNE 14 Networking with Breakout Sessions (private event for fellows) 6/14/2021 10:00 AM to 11:30 AM EDT Mandatory for all dissertation completion and pre-dissertation fellows Through the Science Lens: New Approaches in the Humanities 6/14/2021 1:00 PM to 2:30 PM Mandatory for all dissertation completion and pre-dissertation fellows Moderator: Nicole Shea, CES/Columbia University Speakers: Dominic Boyer - Rice University Arden Hegele - Columbia University Jennifer Edmond - Trinity College Territorial Politics and Federalism Research Network Business Meeting 6/14/2021 1:00 PM to 2:30 PM Business Meeting Chair: Willem Maas - York University TUESDAY, JUNE 15 Mellon-CES Keynote Discussion: Crises of Democracy 6/15/2021 10:00 AM to 11:30 PM Keynote Sponsored by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Mandatory for all dissertation completion and pre-dissertation fellows Chair: Nicole Shea – Director, Council for European Studies Speakers: Eileen Gillooly - Executive Director, Heyman Center for the Humanities, Columbia University Jane Ohlmeyer - Professor of History at Trinity College and Chair of the Irish Research Council 2 European Integration and Political Economy Research Network Speed Mentoring Event 6/15/2021 10:30 AM to 2:30 PM Networking Event Chair: Dermot Hodson - Birkbeck, University of London Knowledge Production and -

Building Knowledge to Build Citizens to Build Cities

2010 International Campus of Excellence Programme UPF CAMPUS ICÀRIA INTERNATIONAL PROJECT Building knowledge To build citizens To build cities Report on the project UPF CAMPUS ICÀRIA INTERNATIONAL PROJECT UPF CAMPUS ICÀRIA INTERNATIONAL PROJECT Building knowledge To build citizens To build cities Report on the project Candiday for the 2010 International Campus of Excellence A much more detailed and complete version of this document can be found at: www.upf.edu/icaria CONTENTS RECTOR’S MESSAGE 7 1. OVERALL PROPOSAL 9 1.1 Perspective and mission 1.2 Theoretical framework 1.3 Campus model and SWOT 1.4 Summary of associates and goals 2. PROJECT REPORT 17 A) Teaching improvement and the EHEA 17 Actions B) Scientific improvement and knowledge transfer 57 Actions C) Transformation of the campus into a comprehensive, social model and its integration 93 within its land setting Actions D) Specialist fields 111 E) Associates 117 F) Internationalisation 135 G) Participation in a sustainable economic model 141 H) Alliances and networks 147 Annexes: List of actions List of tables and diagrams 3. ECONOMIC REPORT 157 3.1 Summarised budget 3.2 Detailed budget 3.3 Chart of actions RECTOR’s message Communis omnium sapientia The Icària International Campus of Excellence project presented by Pompeu Fabra University is based, first and foremost, on the experience the university has gained in the twenty years since it was founded. During this short period, UPF has yielded a successful combination of quality and prestige in teaching whilst upholding an unrelenting commitment to become a leading research institution. The results lay testimony to the fact that the university has embarked on precisely the right course. -

Spain UCEAP Advising Notes

Spain UCEAP Advising Notes COVID-19 Information The COVID-19 pandemic continues to present challenges related to health concerns and international travel. UCEAP has been updating their website’s Coronavirus Notice with up-to-date information. Please check this website for the most up to date information about which programs are running in the 2022-23 academic year. Updated August 2021 Objective of the Advising Notes Document This document is an advising tool written by a Berkeley Study Abroad adviser to review program specific details that may impact a student’s decision to apply for a UCEAP program. The document is not a summary of eligibility requirements, academic, housing, application and other logistical details freely available to students on the UCEAP and BSA websites. If any concerns you have are not addressed on the UCEAP website or in the Advising Notes document, please contact the BSA adviser for this program. RESOURCES Advisor Contact Information For BSA Adviser name, email and advising availability, visit http://studyabroad.berkeley.edu/advising EAP Alums EAP alumni are one of your best resources for information about the program. If you would like to be put in touch with alums, simply send the BSA Adviser an email with your list of questions and the contact information of returnees who have agreed to be contacted will be shared. UCEAP Alum-Created Resources Some of our returnees have created presentations to share with others. You can look at their work through the Student Created Resource Google folder that we will continually update. UCEAP-Created Resources Study Abroad in Latin America and Spain | UCEAP Study Abroad Fair 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eAeLW8GkDBQ&feature=youtu.be Study Abroad in English in Spain and the Americas | UCEAP Study Abroad Fair 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zuv9FWiVsi0&feature=youtu.be Carlos III Univ.