A D+ A- F B+ B- C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary Ray Oaken Comes Home

Your Hometown j i Newspaper f o r s d c The C adiz P 5 sfi*§ssr*‘ *****fiLL Since 1881 |pRINGPORTNMI 4 9 2 8 4 NEWSTAND VOL. 110/No. 20 2 SECTIONS WEDNESDAY, MAY 15,1991 CADIZ, KEN Mary Ray Oaken comes home By Cindy Camper returned home Tuesday National Organization for here.' But I talked to them and Cadiz Record Editor morning for a breakfast in Women and the state alder the Republicans and told them her honor. man's associations. I needed their support if I win With just a few weeks left Oaken knows she has sup Next week Louisville the May primary." for campaigning in the state port in western Kentucky, but Mayor Jerry Abrams is ex Oaken said she is getting .treasurer's office race, says she must campaign hard pected to hold a press confer support from all of Kentucky, ^Cadiz's favorite daughter, and become even more visible ence announcing his en not just the western portion. in the central and northern dorsement of Oaken for the "We are direct mailing our sections of the state in order state treasurer's office. literature. They are being win the race. "I feel good about the race," hand written and addressed. July 4th "I need to carry the First Oaken said. "I think we're Women from all over the state and Second Districts, but I doing really well." are calling and asking if they events set know I also have to do well in Oaken's campaigning has can help," she says. -

Prl-3 Is an Oncogenic Driver in Triple-Negative Breast Cancers And

PRL-3 IS AN ONCOGENIC DRIVER IN TRIPLE-NEGATIVE BREAST CANCERS AND A MEDIATOR OF THE NOVEL ANTICANCER COMPOUND AMPI-109 by HAMID H. GARI B.S., Colorado State University, 2009 M.Phil., University of Cambridge, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cancer Biology Program 2016 This thesis for the Doctor of Philosophy degree by Hamid H. Gari has been approved for the Cancer Biology Program by James DeGregori, Chair M. Scott Lucia Heide Ford Jennifer Diamond Bolin Liu James Lambert, Advisor Date: 05/20/2016 ii Gari, Hamid H. (Ph.D., Cancer Biology) PRL-3 is an Oncogenic Driver in Triple-Negative Breast Cancers and a Mediator of the Novel Anticancer Compound AMPI-109 Thesis directed by Associate Research Professor James Lambert ABSTRACT Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) are among the most aggressive and heterogeneous cancers characterized by a high propensity to invade, metastasize and relapse. AMPI-109 is a novel anticancer compound that is selectively efficacious in inhibiting proliferation and in inducing apoptosis of multiple TNBC subtype cell lines as assessed by activation of pro-apoptotic caspases-3 and 7, PARP cleavage and nucleosomal DNA fragmentation. Because AMPI-109 has little to no effect on growth in the majority of non- TNBC cell lines, we utilized AMPI-109 in a genome-wide shRNA screen to investigate the utility of AMPI-109 as a tool in helping to identify molecular alterations unique to TNBC. Our screen identified the phosphatase, PRL-3, as a putative intracellular target of AMPI-109 and an important driver of TNBC growth, migration and invasion. -

Daily Eastern News: June 16, 1987 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep June 1987 6-16-1987 Daily Eastern News: June 16, 1987 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1987_jun Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: June 16, 1987" (1987). June. 1. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1987_jun/1 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1987 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in June by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. · ·. T 11117,·.... ... tM7 . ..will be mostly suriny and hot. Highs The Dally in the mid-90s with light southeast I winds. Fair and · warm Tuesday night with lows in the low 70s. Mostly sunny astern News ' and continued hot Wednesday with .I highs in the mid-90s. Eastern Illinois University Charleston, Ill. 61920 Vol. 73, No. 157 20 I I I Two Sections, Pages . Eastern aud it report prompts c hanges By MH<E BURKE retained ownership and control of the Staffwriter $661,000 it had raised.. If the Several areas of conflict between university hires and pays the foun Eastern and the stat.e which turnedup dation to raise funds for the in a recent financial audit of the university, the proceedsshould belong university have been resolved, an to the university. If the foundation Eastern administrator said Friday. engages in fund-raising on own its · The stat.e office of the auditor behalf, the university's payment of general recently released a report of fund-raising costs is not justified." its financial audit of East.em for the Thornburgh said the conflict is fiscal year ending June 30, 1986. -

Morocco Quits Libya Treaty Over Criticism

MANCHESTER CONNECTICUT SPORTS MCC gears up Murray Gold gets Carter kills Sox; for another year 25-year sentence lead is cut to ZV2 |MIQ0 3 ... page 11 anrhratrrManchester — A City ol Village Charm linnlh ^ ^ 25 Cents A Claims Morocco quits get tough Libya treaty U scrutiny over criticism Insurance crisis R ABAT, Morocco (AP) — King endangers town Hassan’s meeting July 22-23 in Hassan II said in a letter released Ifrane with Israeli Prime Minister G Friday that he was abrogating a Shimon Peres. By George Loyng 1984 treaty of union with Libya ■'The terms of the Syrian-Libyan Herald Reporter ■ because of Col. Moammar Gadha- communique, published ... at the fi’s criticism of a meeting last end of the visit of (Syrian) When a Glastonbury couple month between Hassan and Israeli President Hafez el-Assad to Libya, notified the town of Manchester Prime Minister Shimon Peres. do not allow our country to earlier this month that they Hassan said in the letter written continue on the path of the union of intended to sue over injuries their Thursday to Gadhafi that the states instituted with your coun teenage son suffered while using a criticism contained in a joint try,” Hassan said in the letter. rope swing at the Buckingham Libyan-Syrian statement issued Hassan became the only Arab Reservoir, it made some officials the day before had reached "the head of state outside Egypt to meet angry. threshold of the intolerable." publicly with the head of the The boy, Matthew Lawrence, He said it was not possible to Jewish nation. -

Vibrations Pullout C

Vibrations Pullout C regain custody of A fisherman becomes in- goes to court to TeteFrance U.S.A. Today CD - ESPN Sports Center Nof 8:30 A.M. 4:30 P.M. - s Work) War II intrigue and a deaf boy In a carnival (60 mm) programs From the World of volved in -- are CD MOVIE: 'Body and Soul' A Bogart. CD Ski School CD - NCAA Instruct tonal Series Report Fiction Zola Drey- - romance Humphrey - Businsas Emlle and the boxer, determined to be a winner, Brennan CD fus Affair,' 'In Performance The Lauren Bacall, Walter - Aerobteise - MOVIE: 'I Go Pogo' 0CD- - NCAA Foot Notre Dame is helped by a reporter who loves 1944 at Pittsburgh Wonderful World of Operetta,' him Leon Isaac Kennedy, Mo- 9:00 A.M. 4:45 P.M. Telestories' The People of Moga-d- or CMy' hammed All 1981 Rated R 11:30 P.M. AB-St- CD MOVIE: of Bw CD - PhM CD ar SportaChatkmge - 'Prince and 'Artvlew Ipoustequy (4 Donahue Guests TBA - WKRP CDOCD-NightHr- w MOVIE: Other Sid of hra) - in ClncmnaU CD- - ESPN Sport Confer - Th 5:00 P.M. the Mountain' Part 1 An Olympic fiD CD - Business Report CD (39 - MOVIE: 'Colombo: -- P.M. IS 8:30 Coi-um- bo CD - MOVIE: Never So Fetr1 An CD MOVIE: 'Hkjti Country hopeful becomes a quadropetglc The Most Crucial Game' Lt rmy - -- - BricJeshead Revisited captain, commanding a unit after a near-fat- al accident on vie CD Newhart The com- investigates the slaying of of Burmese natives, orders his - MOVIE: The Formula' ski slopes Beau Bridges, Marilyn munity encourages Dick to be- 10:15 P.M. -

Premium Channels

Premium Channels 1 Starz Pack 2 Showtime Pack 1815 StarzENCORE 1835 Showtime 1816 StarzENCORE Action 1837 Showtime 2 1817 StarzENCORE Black 1841 Showtime Beyond 1818 StarzENCORE Classic 1840 Showtime Extreme 1819 StarzENCORE Westerns 1842 Showtime Next 1820 StarzENCORE Suspense 1838 Showtime Showcase 1821 Starz 1843 Showtime Women 1822 Starz Cinema 1836 The Movie Channel 1 1823 Starz Comedy 1839 The Movie Channel 2 1824 Starz Edge 1825 Starz in Black 3 Starz & Showtime Double Pack 1826 Starz Kids n Family Bundled for a great deal! Recommended Devices* STREAMING DEVICE COMPATIBLE HD QUALITY NOTES The Best Way to Experience TV. ROKU Ultra YES HDTV/4K Recommended ROKU4 YES HDTV/4K Recommended Anytime. Anywhere. ROKU3 YES HDTV Recommended ROKU Premier YES HDTV/4K Recommended ROKU Premier + YES HDTV/4K Recommended ROKU Express NO HDTV May Work, Not Recommended Business Hours: Toll Free: 877.655.7627 ROKU Express + NO HDTV May Work, Not Recommended Monday–Friday Bergen (507) 832-7000 ROKU Streaming Stick NO HDTV/4K May Work, Not Recommended 8:00 am to 5:00 pm Bingham Lake (507) 832-7000 ROKU Streaming Stick + NO HDTV/4K May Work, Not Recommended Onsite Technical Support: Brewster (507) 842-7000 ROKU 1/2/Stick NO Not Recommended Monday–Friday Heron Lake (507) 793-7000 Android TV YES HDTV If you have an Android TV, Android set top 8:00 am to 4:30 pm Lakefield (507) 662-7000 box or Android mobile device, search for Jackson (507) 849-7000 “Southwest Stream” in the Google Play Store After Hours Technical Support Okabena (507) 853-7000 Web Browser YES HDTV Any HTML5 Compatible Browser (Edge, is always available during Round Lake (507) 945-0010 Chrome, Opera, Safari, Firefox…) non-business hours. -

A "Pay Or Play" Experiment to Improve Children's Educational Television

Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 62 Issue 2 Article 3 4-2010 A "Pay or Play" Experiment to Improve Children's Educational Television Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Communications Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Education Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Levi, Lili (2010) "A "Pay or Play" Experiment to Improve Children's Educational Television," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 62 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol62/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A "Pay or Play" Experiment to Improve Children's Educational Television Lill Levi* I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 276 II. THE HISTORY OF Ti-E FCC's CHILDREN'S EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION PROGRAMMING RULES ...................................... 286 III. THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE FCC'S CHILDREN'S EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION PROGRAMMING RULES .............. 293 IV. THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE FCC's APPROACH .................... 304 A. Regulatory Goals in Tension ........................................... -

Detroit Tues, July 29, 1975 from Detroit News 2 WJBK-CBS * 4 WWJ-NBC * 7 WXYZ-ABC * 9 CBET-CBC

Retro: Detroit Tues, July 29, 1975 from Detroit News 2 WJBK-CBS * 4 WWJ-NBC * 7 WXYZ-ABC * 9 CBET-CBC (and some CTV) * 20 WXON-Ind * 50 WKBD-Ind * 56 WTVS-PBS [The News didn't list TVO, Global or CBEFT] Morning 6:05 7 News 6:19 2 Town & Country Almanac 6:25 7 TV College 6:30 2 Summer Semester 4 Classroom 56 Varieties of Man & Society 6:55 7 Take Kerr 7:00 2 News (Frank Mankiewicz) 4 Today (Barbara Walters/Jim Hartz; Today in Detroit at 7:25 and 8:25) 7 AM America (Bill Beutel) 56 Instructional TV 7:30 9 Cartoon Playhouse 8:00 2 Captain Kangaroo 9 Uncle Bobby 8:30 9 Bozo's Big Top 9:00 2 New Price is Right 4 Concentration 7 Rita Bell "Miracle of the Bells" (pt 2) 9:30 2 Tattletales 4 Jackpot 9 Mr. Piper 50 Jack LaLanne 9:55 4 Carol Duvall 10:00 2 Spin-Off 4 Celebrity Sweepstakes 9 Mon Ami 50 Detroit Today 56 Sesame Street 10:15 9 Friendly Giant 10:30 2 Gambit 4 Wheel of Fortune 7 AM Detroit 9 Mr. Dressup 50 Not for Women Only 11:00 2 Phil Donahue 4 High Rollers 9 Take 30 from Ottawa 50 New Zoo Revue 56 Electric Company 11:30 4 Hollywood Squares 7 Brady Bunch 9 Family Court 50 Bugs Bunny 56 Villa Alegre Afternoon Noon 2 News (Vic Caputo/Beverly Payne) 4 Magnificent Marble Machine 7 Showoffs 9 Galloping Gourmet 50 Underdog 56 Mister Rogers' Neighborhood 12:30 2 Search for Tomorrow 4 News (Robert Blair) 7 All My Children 9 That Girl! 50 Lucy 56 Erica-Theonie 1:00 2 Love of Life (with local news at 1:25) 4 What's My Line? 7 Ryan's Hope 9 Showtime "The Last Chance" 50 Bill Kennedy "Hell's Kitchen" 56 Antiques VIII 1:30 2 As the World Turns 4 -

Mocker Mania Strikes Lowell This Weekend

,eAG 4 25' ; "NS' 300K B(WDERl,* 9 Wimmr. BICHicam 49284 The Grand Valley Ledger Volume 8, Issue 36 Serving Lowell Area "jjSf Readers Since 1893 July 11. 1984 Mocker Mania strikes Lowell this weekend This Year's Gus Macker ture of just how fast this annual with 10 to 15 contestants ex- Tournament 'The llth Annual mania is growing. pected to be in the running. Cary £ New and Improved 'Olympic Macker Week officially began Berglund of WOTB, Jeanne Style' One and Only Original here in Mackervillet U.S.A. Norcross of WOTV, Joe Conklin *Ycs We're Building an Empire' (otherwise known as Lowell) a sportswriter for the Grand Rap- M Gus Macker (for President '84) Monday evening with a Be ids Press, Lowell Mayor Jim All-World Invitational Three- Kind to the Neighbors" potluck Maatman, Steve Knight of on-Three Outdoor Backyard dinner in the front yard of Gus' WZZM, Randy Franklin from 'Back to the Streets' Basketball parents Dick and Bonnie WKWM, Georgia Smith an ex- l oumament" is going to be big- McNeal. The dinner was a way perienced beauty pageant con- iier and better than ever before. of saying 'lhank you" to all the testant and Gus Macker's No. I 0 * What's new about that? , you neighbors who are so under- fan Mary Ann Gwatkins will say. Well consider that this standing of the annual serve as judges. The judging be- year's tourney will feature 470 toummanet. Tuesday had a "Hall gins at 7:30 P.M. There will also 0 four person teams, up from last of Fame Game" scheduled on the be a special break dancing exhib- year's 391 and will be spread out main court. -

Report for the APFI on the Television Market Landscape in the UK and Eire

APFI Report: UK, Eire and US Television Market Landscape • Focusing on childrens programming • See separate focus reports for drama MediaXchange encompasses consultancy, development, training and events targeted at navigating the international entertainment industry to advance the business and content interests of its clients. This report has been produced solely for the information of the APFI and its membership. In the preparation of the report MediaXchange reviewed a range of public and industry available sources and conducted interviews with industry professionals in addition to providing MediaXchange’s own experience of the industry and analysis of trends and strategies. MediaXchange may have consulted, and may currently be consulting, for a number of the companies or individuals referred to in these reports. While all the sources in the report are believed to represent current and accurate information, MediaXchange takes no responsibility for the accuracy of information derived from third-party sources. Any recommendations, data and material the report provides will be, to the best of MediaXchange’s judgement, based on the information available to MediaXchange at the time. The reports contain properly acknowledged and credited proprietary information and, as such, cannot under any circumstances be sold or otherwise circulated outside of the intended recipients. MediaXchange will not be liable for any loss or damage arising out of the collection or use of the information and research included in the report. MediaXchange Limited, 1 -

TV RECORD for COLOMA-HARTFORD- WATERVLIET TRI-CITY RECORD 25C VOL.103 • No

00 0 522 190 02- liBR,bV colow^ pblC Hartford woman is instant Police Coloma and Watervliet folks Local sports For cable & TV listings, see the friend of 'hearing ear dog* News meet 'Down Under' & Outdoors See page 5 See page 2 See page 13 See pages 15 & 16 TV RECORD FOR COLOMA-HARTFORD- WATERVLIET TRI-CITY RECORD 25C VOL.103 • No. 9 RED ARROW EDITION OF THE WATERVLIET RECORD March 4,1987 WATERVLIET H.S. VALEDICTORIAN Adult foster home ordinance adopted by Watervliet City Lawsuit filed against City for denying building permit within sixty days of Its effective sioners that an appeal of the & SALUTATORIAN date." state's decision to license an Watervliet High School Is Mayor Ed Campbell said the adult foster care facility on Van- Watervliet City Commis- proud to announce the selection care and day care facilities. It ordinance could become effec- nater Court is proceeding. Jones sioners voted unanimously In further requires inspection of of the valedictorian and tive thirty days after it Is publish- also Indicated that litigation favor of a recently-drafted or- such properties by the City salutatorlan for the 1987 ed for the public. The ordinance protesting the City's repeal of a dinance requiring registration building Inspector and the is- graduating class. provides for fines and jail building permit for the site Is and permitting regulation of suance of a certificate of com- Mike Grear, son of Mr. and sentences not to exceed $500.00 also pending. adult foster care and day care pliance with regard to all Mrs. James Grear, Is named and ninety days for the first In other business. -

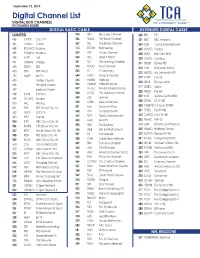

Channel Lineup

September 12, 2019 Digital Channel List DIGITAL BOX CHANNELS HD CHANNELS BOLDED DIGITAL BASIC CABLE EXTENDED DIGITAL CABLE LIMITED 535 DSC Discovery Channel 200 FYI FYI 486 CRTTV Court TV 536 TRAVL The Travel Channel 201 BBC BBC America 487 COMET Comet 537 DIS The Disney Channel 204 GSN Game Show Network 488 BOUNCE Bounce 538 BOOM Boomerang 205 YOUTO Youtoo 489 STADIUM Stadium 539 HIST History Channel 208 WILD Nat Geo Wild 490 LAFF Laff 540 APL Animal Planet 209 COOK Cooking 491 CHARG Charge 541 TLC The Learning Channel 211 DISXD Disney XD 542 FOOD Food Network 492 TBDTV TBD 212 HUB Discovery Family 543 ID ID Discovery 493 IPTV IPTV World 213 MDSTD My Destination.TV 544 HGTV Home & Garden 494 MeTV Me TV 217 HUNT Pursuit 545 HLMRK Hallmark 495 Hartley Church 218 DISJR Disney Junior 496 Primghar Church 546 HLMKM Hallmark Movie 219 QUBO Qubo 497 Sanborn Church 547 msnbc National Broadcasting 220 PIXLD Pixl HD 498 IPTVK IPTV Kids 548 OUTD The Outdoor Channel 227 JUST Justice Central HD 499 ESCAPE Escape 549 LIFE Lifetime 228 ESTVD ES.TV HD 500 HILL Hillsong 550 CNBC News & Business 230 CMDYD Comedy.TV HD 501 THIS THIS (Sioux City, IA) 551 Syfy Science Fiction 231 PETSD Pet.TV HD 502 JUCE JUCE TV 552 FSN Fox Sports North 232 CARSD Cars.TV HD 503 IPTV Create 553 FETV Family Entertainment 233 FMHD FM HD 504 KTIV NBC (Sioux City, IA) 554 MAV MAV TV 234 LRW Lifetime Real Women 506 KMEG CBS (Sioux City, IA) 555 FBN Fox Business 235 HLMKD Hallmark Drama 507 KPTH Fox 44 (Sioux City, IA) 556 A&E Arts & Entertainment 237 RCPHD Recipe.TV HD 508 KSIN PBS (Sioux City, IA) 557 FX Fox Network 509 KCAU ABC (Sioux City, IA) 558 CNN Cable News Network 241 IFCHD Independent Film 510 SCH School (HMS/SOS) 559 FNC Fox News Channel 243 WEHD Women’s Entert.