Waldemar Nods

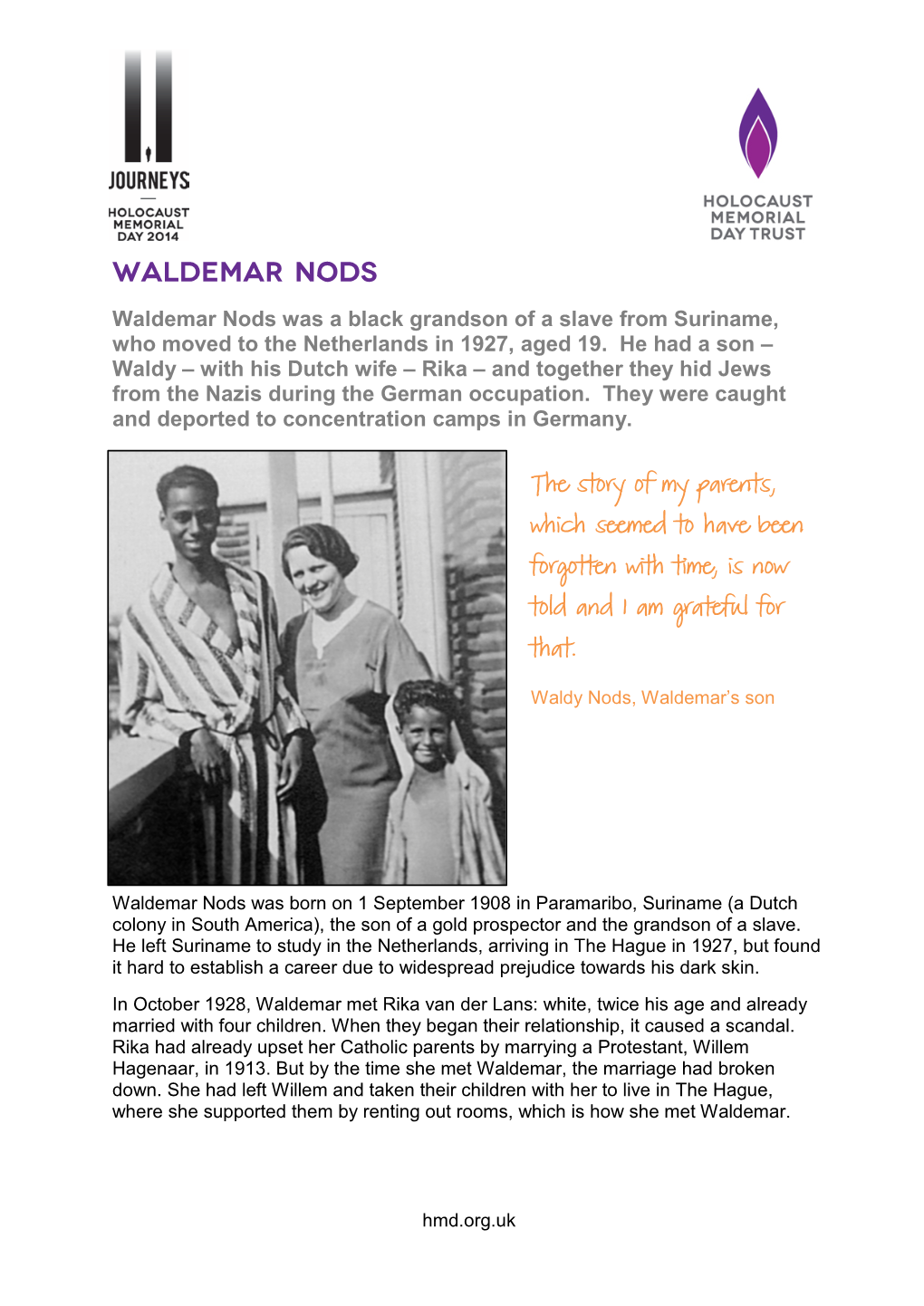

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HERC 1082 Educators Week Program 9-20

HERC Invites You to Our Virtual Events for Statewide Recognition of Holocaust Education Week November 9th-12th Monday, November 9 – Dr. Mark Wygoda, speaks about “In the Shadow of the Swastika”, a book based upon his father’s memoirs of WWII. Sponsored by He was known first as a Warsaw ghetto smuggler, then as Comandante Enrico. He traveled under false identity papers and worked at a German border patrol station. Throughout the years of the Holocaust, Hermann Wygoda lived a life of narrow escapes, daring masquerades, and battles Co-sponsored by that almost defy reason. FREE to attend virtually online via www.facebook.com/events/353647666012056/ Tuesday, November 10 – Dr. Oren Baruch Stier – Professor of Religious Studies and Director, FIU Holocaust and Genocide Studies Program Kristallnacht: The End of the Beginning and the Beginning of the End The state-sponsored, “spontaneous,” premeditated pogrom on November 9-10, 1938 – known widely as Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass – represents both a historic and symbolic turning point in the Nazi assault against European Jewry. Commemorated widely, it remains relevant to anyone interested in understanding the evolution of hate. Join FIU’s Oren Stier and HERC as we explore the significance of this date and reflect on why it continues to matter. Sponsored by Zoom link invite coming soon Thursday, November 12 – Dr. Robert Watson author The Nazi Titanic: The Incredible Untold Story of a Doomed Ship in World War II. Built in 1927, the German ocean liner SS Cap Arcona was the greatest ship since Co-sponsored by the RMS Titanic and one of the most celebrated luxury liners in the world. -

2018 Disseminator Grant

2018 Disseminator Grant: Project Title: Unraveling the Past to Create a Better and Inclusive Future Jacqueline Torres-Quinones, Ed.D [email protected] South Dade Senior High School 7701 ONCE I THOUGHT THAT ANTI-SEMITISM HAD ENDED; TODAY IT IS CLEAR TO ME THAT IT WILL PROBABLY NEVER END. - ELIE WIESEL, JEWISH SURVIVOR For Information concerning ideas with Impact opportunities including Adapter and Disseminator grants, please contact: Debra Alamo, interim Program Manager Ideas with Impact The Education Fund 305-558-4544, Ext 105 Email: [email protected] www.educationfund.org Acknowledgment: First and foremost, the Unraveling the Past to Create a Better and Inclusive Future Grant, has led to the development of a practical and relevant Holocaust unit filled with various lessons that can be chunked and accessible resources for secondary teachers to use. The supportive guidance was provide by Eudelio Ferrer-Gari , a social science guru- [email protected] from Dr. Rolando Espinosa K-8 Center, The Echoes and Reflections, and the Anti-Defamation League Organizations. Within this grant, teachers will be able to acquire knowledge of how to help students understand the Holocaust better and assist them to make critical thinking connective decisions as well of how they can make a positive difference today- when dealing with challenging social and political issues. Resources used throughout the grant: Founded in 2005, Echoes & Reflections is a comprehensive Holocaust education program that delivers professional development and a rich array of resources for teachers to help students make connections to the past, gain relevant insight into human dilemmas and difficult social challenges, and to determine their roles and responsibility in the world around them. -

Aanspraak June 2018 English

June 2018 AanspraakAfdeling Verzetsdeelnemers en Oorlogsgetroffenen Wim Aloserij, the last survivor of the Cap Arcona shipwreck bears no grudges Contents Page 4 Speaking for your benefit. Page 5 Remembrance speech of 4 May 2018 at Dam Square, Amsterdam. By Director of the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP) Kim Putters. Page 6-9 The last survivor of the Cap Arcona shipwreck bears no grudges. Wim Aloserij survived the concentration camps in Amersfoort, Husum, Neuengamme and the bombing of the SS Cap Arcona prison ship by the Allies. Page 10-12 ‘The bombing of the Bezuidenhout neighbourhood ruined me physically, but not mentally.’ As a child, in 1945, former Dutch Labour Party (PvdA) mayor Hans Ouwerkerk lost his father and was severely injured by a British bomb. Page 13-16 Not having a ‘J’ stamped on my identity card gave me my freedom back. The Jewish dressmaker Marga was able to do resistance work undetected from Amsterdam. Aanspraak - June 2018 - 2 Page 17 News from the Client Council. Page 18 Questions and answers. No rights may be derived from this text. Translation: SVB, Amstelveen. Aanspraak - June 2018 - 3 Speaking for your benefit In Italy, every secondary school pupil is encouraged Meditate that this came about: to read ‘Se questo è un uomo’ (1947) by the Italian I commend these words to you, Jewish author Primo Levi. Levi was a chemist and Carve them in your hearts a survivor of Auschwitz. At home, in the street, Going to bed, rising: This book, which was published in English under Repeat them to your children. -

Análisis De Los Hundimientos De Buques De Carga Y Pasaje Durante La Segunda Guerra Mundial

Análisis de los hundimientos de buques de carga y 4 de febrero pasaje durante la 2013 Segunda Guerra Mundial Autor: Angel Sevillano Maldonado Tutor: Francesc Xavier Martínez de Osés Diplomatura en Navegación Marítima Trabajo Final de Carrera Facultad de Náutica de Barcelona – UPC DEDICATORIA A mis hermanas, por todo el apoyo e interés mostrado hacia este trabajo. AGRADECIMIENTOS Al primer oficial Néstor Rodríguez, del buque Playa de Alcudia, por darme a conocer muchos de los desastres analizados en el trabajo, al profesor Xavier Martínez de Osés, por su gran colaboración y a todos aquellos que me han brindado su ayuda cuando ha sido necesario. Gracias a todos. Análisis de los hundimientos de buques de carga y pasaje durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial INDICE 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ................................................................................... 9 2. LA SEGUNDA GUERRA MUNDIAL .......................................................10 2.1 INTRODUCCIÓN ...............................................................................10 2.2 PRINCIPALES ESCENARIOS DEL TEATRO BÉLICO..........................12 2.2.1 LA GUERRA DEL PACIFICO ..............................................................12 2.2.2 LA GUERRA SUBMARINA DEL MAR BÁLTICO.............................17 3. ANÁLISIS DE LOS NAUFRAGIOS.........................................................20 3.1 MV WILHELM GUSTLOFF..................................................................20 3.1.1 DATOS GENERALES DEL BUQUE ..............................................20 3.1.2 -

Record of Witness Testimony 124

POLISH SOURCE INSTITUTE 104 IN LUND Dädesjö, 14 January 1946 Testimony received by Institute Assistant Bożysław Kurowski, LL M transcribed Record of Witness Testimony 124 Here stands Mr Bronisław Berdyś born on 18 July 1922 in Cracow , occupation plumber religion Roman Catholic , parents’ forenames Wiktor and Maria last place of residence in Poland ulica Wilga 16 [lit. ‘16 Wilga Street’], Cracow current place of residence Dädesjö who – having been cautioned as to the importance of truthful testimony as well as to the responsibility for, and consequences of, false testimony – hereby declares as follows: I was interned at the concentration camp in Auschwitz from April 1941 to 12 March 1943 as a political prisoner – bearing the number 12863 (?) and wearing a red -coloured triangle with the letter ‘P’. I was later interned in the Neuengamme concentration camp from 15 March 1943 to 17 April 1945 No. 18889; and finally, from 17 April to 3 May 1945, I underwent evacuation from the Neuengamme camp to Lübeck. Asked whether, with regard to my internment and my labour at the concentration camp, I possess any particular knowledge about how the camp was organized, how prisoners were treated, their living and working conditions, medical and pastoral care, the hygienic conditions in the camp, or any particular events concerning any aspect of camp life, I state as follows: The testimony consists of seven pages of handwriting and describes the following: 1. Evacuation of the concentration camp in Neuengamme to Lübeck aboard trains on 17 April 1945 – Hunger, thirst 2. Embarkation of approximately 14,000 prisoners aboard the SS Thielbek and SS Cap Arcona – Daily routine, Appells [roll call assemblies, Ger.], food provisions – One prisoner’s unsuccessful attempt at escape from the Cap Arcona 3. -

Whitney Young's Fight for Civil Rights Please

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVE S AT KANSAS CITY June 2016 National Archives to Screen The Powerbroker: Inside This Issue Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights THE NAZI TIITANIC 2 BOOK DISCUSSION On Thursday, June 9 at 6:30 p.m., the National Archives at Kansas City will screen the documentary The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights. Post-film discussion will EDUCATORS 3 be led by Gwen Grant, President and CEO of the Urban League. A free light reception will WORKSHOP precede the film at 6:00 p.m. HIDDEN TREASURES 5-7 FROM THE STACKS Civil rights leader Whitney Young, Jr. has no national holiday bearing his name. You will not find him in most history books. In fact, few today know his name, much Upcoming Events less his accomplishments. Yet, he was at the heart of the Unless noted, all events civil rights movement – an inside man who broke down are held at the the barriers that held back African Americans. Young National Archives shook the right hands, made the right deals, and 400 West Pershing Road opened the doors of opportunity that had been locked Kansas City, MO 64108 tightly through the centuries. Unique among black leaders, the one-time executive director of the JUNE 9 - 6:30 P.M. National Urban League took the fight directly to the powerful white elite, gaining allies in business and FILM SCREENING: THE government. In the Oval Office, Young advised POWERBROKER: Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, and guided WHITNEY YOUNG’S each along a path toward historic change. -

Ned. Rode Kruis - Kampen En Gevangenissen 3

Nummer Toegang: 2.19.321 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Rode Kruis - Kampen en Gevangenissen Versie: 19-08-2020 Het Nederlandse Rode Kruis en het Nationaal Archief Nationaal Archief, Den Haag (c) 2019 This finding aid is written in Dutch. 2.19.321 Ned. Rode Kruis - Kampen en Gevangenissen 3 INHOUDSOPGAVE Beschrijving van het archief.....................................................................................11 Aanwijzingen voor de gebruiker...............................................................................................12 Openbaarheidsbeperkingen......................................................................................................12 Beperkingen aan het gebruik....................................................................................................12 Materiële beperkingen.............................................................................................................. 12 Andere toegang......................................................................................................................... 12 Aanvraaginstructie.....................................................................................................................12 Citeerinstructie.......................................................................................................................... 12 Archiefvorming..........................................................................................................................13 Geschiedenis van de archiefvormer..........................................................................................13 -

Análisis De Los Hundimientos De Buques De Carga Y Pasaje Durante La Segunda Guerra Mundial

Análisis de los hundimientos de buques de carga y 4 de febrero pasaje durante la 2013 Segunda Guerra Mundial Autor: Angel Sevillano Maldonado Tutor: Francesc Xavier Martínez de Osés Diplomatura en Navegación Marítima Trabajo Final de Carrera Facultad de Náutica de Barcelona – UPC DEDICATORIA A mis hermanas, por todo el apoyo e interés mostrado hacia este trabajo. AGRADECIMIENTOS Al primer oficial Néstor Rodríguez, del buque Playa de Alcudia, por darme a conocer muchos de los desastres analizados en el trabajo, al profesor Xavier Martínez de Osés, por su gran colaboración y a todos aquellos que me han brindado su ayuda cuando ha sido necesario. Gracias a todos. Análisis de los hundimientos de buques de carga y pasaje durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial INDICE 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ................................................................................... 9 2. LA SEGUNDA GUERRA MUNDIAL .......................................................10 2.1 INTRODUCCIÓN ...............................................................................10 2.2 PRINCIPALES ESCENARIOS DEL TEATRO BÉLICO..........................12 2.2.1 LA GUERRA DEL PACIFICO ..............................................................12 2.2.2 LA GUERRA SUBMARINA DEL MAR BÁLTICO.............................17 3. ANÁLISIS DE LOS NAUFRAGIOS.........................................................20 3.1 MV WILHELM GUSTLOFF..................................................................20 3.1.1 DATOS GENERALES DEL BUQUE ..............................................20 3.1.2 -

Record of Witness Testimony 333

POLISH SOURCE INSTITUTE IN LUND Lund, 29 May 1946 Testimony received by Institute Assistant Bożysław Kurowski, LL M transcribed Record of Witness Testimony 333 Here stands Mr Zbigniew Foltyński born on 29 January 1922 in Warsaw , occupation student at the Technical College of Warsaw religion Roman Catholic , parents’ forenames Jan and Irena last place of residence in Poland Warsaw, ulica Domeyki 12 [lit. ‘12 Domeyki Street’] current place of residence Sundhultsbrunn who – having been cautioned as to the importance of truthful testimony as well as to the responsibility for, and consequences of, false testimony – hereby declares as follows: I was interned at the concentration camp in Stutthof, near Gdańsk from 30 September 1944 to 18 October 1944 as a political prisoner – bearing the number 92142 (?) and wearing a red -coloured triangle with the letter ‘P’. I was later interned in Neuengamme, [bearing the] number 60124 from 20 October 1944 to approximately 20 April 1945; lastly, I spent a roughly fourteen-day period at sea on a camp evacuation transport aboard the SS Cap Arcona and SS Athen until 3 May 1945. On 27 September 1944, I was arrested in Warsaw as an insurgent. Asked whether, with regard to my internment and my labour at the concentration camp, I possess any particular knowledge about how the camp was organized, how prisoners were treated, their living and working conditions, medical and pastoral care, the hygienic conditions in the camp, or any particular events concerning any aspect of camp life, I state as follows: The testimony consists of eight pages of handwriting and describes the following: I. -

Catalogue 235 OCTOBER 2020

1 Catalogue 235 OCTOBER 2020 RARE GROUP: $65 each 235/86. (11133) Glunicke, LtCol G.J. The Campaign in Bohemia - 1866 (Special Campaign Series No. 6). Swan Sonnenschein & Co, London, 1907. 235/90. (11135) Maude, Col. F.N. (RE). The Leipzig Campaign 1813. (Special Campaign Series #7) Swan Sonnenschein & Co, London, 1908 235/99. (11134) Sedgwick, Captain F.R. (RFA). The Russo-Japanese War 1904. (Special Campaign Series #10) Swan Sonnenschein & Co, London, 1909. 2 Glossary of Terms (and conditions) INDEX Returns: books may be returned for refund within 7 days and only if not as described in the catalogue. CATEGORY PAGE NOTE: If you prefer to receive this catalogue via email, let us know on in- [email protected] Aviation 3 My Bookroom is open each day by appointment – preferably in the afternoons. Give me a call. Espionage 4 Abbreviations: 8vo =octavo size or from 140mm to 240mm, ie normal size book, 4to = quarto approx 200mm x 300mm (or coffee table size); d/w = dust wrapper; pp = pages; vg cond = (which I thought was self explanatory) very good condition. Military Biography 6 Other dealers use a variety including ‘fine’ which I would rather leave to coins etc. Illus = illustrations (as opposed to ‘plates’); ex lib = had an earlier life in library service (generally public) and is showing signs of wear (these books are generally Military General 7 1st editions mores the pity but in this catalogue most have been restored); eps + end papers, front and rear, ex libris or ‘book plate’; indicates it came from a private collection and has a book plate stuck in the front end papers. -

107 the "Perfect" Phone Adapter the Device Which Makes It Easy to Attach Head- Phones to Any Radio Set

THE MARCH 1937 11 EX The All -wave DX Log of the World The Story of Television The Mystery DX Contest Complete Station -Identifying Shortwave List No. 107 The "Perfect" Phone Adapter The device which makes it easy to attach head- phones to any radio set. Anyone can install it, without tools, in no time at all. It cannot harm the receiver and the operation of the set is not affected in any way. IDEAL FOR THE HARD -OF-HEARING Those who are very hard of hearing can enjoy radio reception by using our new HOH Model Phone Adapter. It gives sufficient volume on the headphones without it being necessary to increase the volume of the receiver above normal. THE VERY BEST HEADPHONES For use with the Perfect Phone Adapter, we rec- ommend the Trimm Featherweight Headphones. They weigh only 4 ounces and can be worn for hours, without fatigue. Very sensitive, designed for use by commercial operators, they get the weak signals which other, less sensitive 'phones fail to register. We pay the postage on all orders. If you live in Ohio add 3% for Sales Tax The HOH Model Perfect Phone Adapter with Trimm Featherweight Headphones .. $12.00 The HOH Model Perfect Phone Adapter with a good pair of Trimm Headphones.... $6.70 In ordering be sure to give The Radex Press make and model of receiver and a list of the tubes used. Conneaut. Maio We ! v V T % uf 23 tube SC l WORLD SUPREMACY E. H. SCOTT SDORY after story-page after page the fascinating adventures SCOTT SCOTT receivers are not sold - of unique and exciting expe- owners unfold in this mountain of through dealers but direct from riences-written by SCOTT owners- EVIDENCE-conclusively establsh- SCOTT Laboratories where makes this 24-page Brochure unques- ing the world supremacy of the SCOTT. -

Copyright British Foreign Office Russia Correspondence Guide To

%ULWLVK)RUHLJQ2IILFH5XVVLDFRUUHVSRQGHQFHJXLGHWRWKHVFKRODUO\ UHVRXUFHVPLFURILOPHGLWLRQRIWKH3XEOLF5HFRUG2IILFH&ROOHFWLRQ %G>@ :LOPLQJWRQ'HO XUQQEQGHEYEEVE 'LH3')'DWHLNDQQHOHNWURQLVFKGXUFKVXFKWZHUGHQ Copyright Das Copyright für alle Webdokumente, insbesondere für Bil- The Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (BSB) owns the copyright for der, liegt bei der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek. Eine Folge- all web documents, in particular for all images. Any further use verwertung von Webdokumenten ist nur mit Zustimmung der of the web documents is subject to the approval of the Baye- Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek bzw. des Autors möglich. Exter- rische Staatsbibliothek and/or the author. External links to the ne Links auf die Angebote sind ausdrücklich erwünscht. Eine offer of the BSB are expressly welcome. However, it is illegal unautorisierte Übernahme ganzer Seiten oder ganzer Beiträge to copy whole pages or complete articles or parts of articles oder Beitragsteile ist dagegen nicht zulässig. Für nicht-kom- without prior authorisation. Some individual materials may be merzielle Ausbildungszwecke können einzelne Materialien ko- copied for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that piert werden, solange eindeutig die Urheberschaft der Autoren the authorship of the author(s) or of the Bayerische Staatsbibli- bzw. der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek kenntlich gemacht wird. othek is indicated unambiguously. Eine Verwertung von urheberrechtlich geschützten Beiträgen Unless provided otherwise by the copyright law, it is illegal and und Abbildungen der auf