Catarpe in the Atacama Desert of Chile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rain Shadows

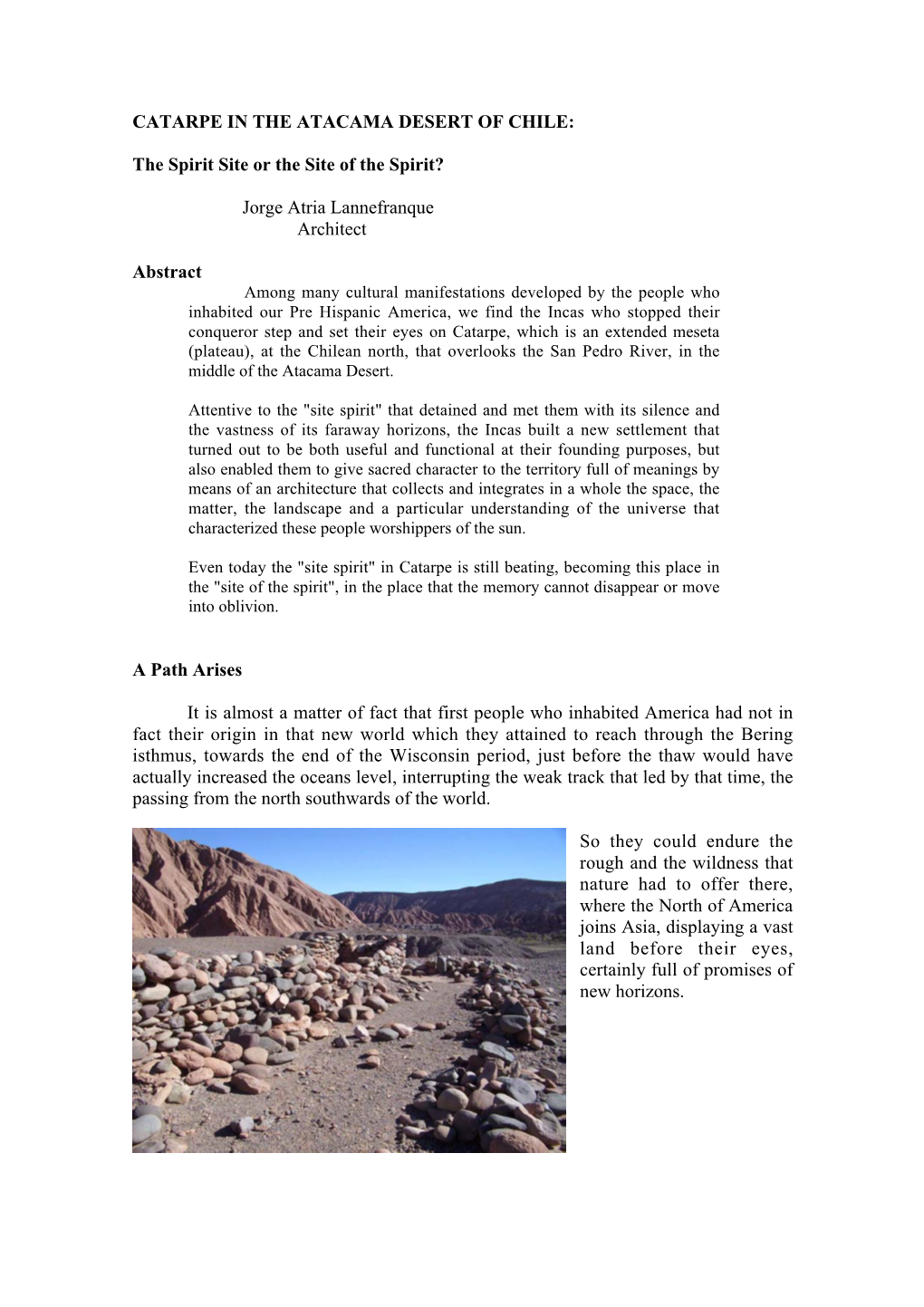

WEB TUTORIAL 24.2 Rain Shadows Text Sections Section 24.4 Earth's Physical Environment, p. 428 Introduction Atmospheric circulation patterns strongly influence the Earth's climate. Although there are distinct global patterns, local variations can be explained by factors such as the presence of absence of mountain ranges. In this tutorial we will examine the effects on climate of a mountain range like the Andes of South America. Learning Objectives • Understand the effects that topography can have on climate. • Know what a rain shadow is. Narration Rain Shadows Why might the communities at a certain latitude in South America differ from those at a similar latitude in Africa? For example, how does the distribution of deserts on the western side of South America differ from the distribution seen in Africa? What might account for this difference? Unlike the deserts of Africa, the Atacama Desert in Chile is a result of topography. The Andes mountain chain extends the length of South America and has a pro- nounced influence on climate, disrupting the tidy latitudinal patterns that we see in Africa. Let's look at the effects on climate of a mountain range like the Andes. The prevailing winds—which, in the Andes, come from the southeast—reach the foot of the mountains carrying warm, moist air. As the air mass moves up the wind- ward side of the range, it expands because of the reduced pressure of the column of air above it. The rising air mass cools and can no longer hold as much water vapor. The water vapor condenses into clouds and results in precipitation in the form of rain and snow, which fall on the windward slope. -

What Makes a Complex Society Complex?

What Makes a Complex Society Complex? The Dresden Codex. Public domain. Supporting Questions 1. How did the Maya use writing to represent activities in their culture? 2. What did the Aztecs do to master their watery environment? 3. Why were roads important to the Inca Empire? Supporting Question 1 Featured Source Source A: Mark Pitts, book exploring Maya writing, Book 1: Writing in Maya Glyphs: Names, Places & Simple Sentences—A Non-Technical Introduction to Maya Glyphs (excerpt), 2008 THE BASICS OF ANCIENT MAYA WRITING Maya writing is composed of various signs and symbol. These signs and symbols are often called ‘hieroglyphs,’ or more simply ‘glyphs.’ To most of us, these glyphs look like pictures, but it is often hard to say what they are pictures of…. Unlike European languages, like English and Spanish, the ancient Maya writing did not use letters to spell words. Instead, they used a combination of glyphs that stood either for syllables, or for whole words. We will call the glyphs that stood for syllables ‘syllable glyphs,’ and we’ll call the glyphs that stood for whole words ‘logos.’ (The technically correct terms are ‘syllabogram’ and ‘logogram.’) It may seem complicated to use a combination of sounds and signs to make words, but we do the very same thing all the time. For example, you have seen this sign: ©iStock/©jswinborne Everyone knows that this sign means “one way to the right.” The “one way” part is spelled out in letters, as usual. But the “to the right” part is given only by the arrow pointing to the right. -

An Integrated Analysis of the March 2015 Atacama Floods

PUBLICATIONS Geophysical Research Letters RESEARCH LETTER An integrated analysis of the March 2015 10.1002/2016GL069751 Atacama floods Key Points: Andrew C. Wilcox1, Cristian Escauriaza2,3, Roberto Agredano2,3,EmmanuelMignot2,4, Vicente Zuazo2,3, • Unique atmospheric, hydrologic, and 2,3,5 2,3,6 2,3,7,8 2,3 9 geomorphic factors generated the Sebastián Otárola ,LinaCastro , Jorge Gironás , Rodrigo Cienfuegos , and Luca Mao fl largest ood ever recorded in the 1 2 Atacama Desert Department of Geosciences, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, USA, Departamento de Ingeniería Hidráulica y 3 • The sediment-rich nature of the flood Ambiental, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, Centro de Investigación para la Gestión Integrada de resulted from valley-fill erosion rather Desastres Naturales (CIGIDEN), Santiago, Chile, 4University of Lyon, INSA Lyon, CNRS, LMFA UMR5509, Villeurbanne, France, than hillslope unraveling 5Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, USA, 6Escuela de • Anthropogenic factors increased the fi 7 consequences of the flood and Ingeniería Civil, Ponti cia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile, Centro de Desarrollo Urbano Sustentable 8 highlight the need for early-warning (CEDEUS), Santiago, Chile, Centro Interdisciplinario de Cambio Global, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, systems Chile, 9Departamento de Ecosistemas y Medio Ambiente, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile Supporting Information: Abstract In March 2015 unusual ocean and atmospheric conditions produced many years’ worth of • Supporting Information S1 rainfall in a ~48 h period over northern Chile’s Atacama Desert, one of Earth’s driest regions, resulting in Correspondence to: catastrophic flooding. -

Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor

Silva Collins, Gabriel 2019 Anthropology Thesis Title: Making the Mountains: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor: Antonia Foias Advisor is Co-author: None of the above Second Advisor: Released: release now Authenticated User Access: No Contains Copyrighted Material: No MAKING THE MOUNTAINS: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads by GABRIEL SILVA COLLINS Antonia Foias, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Anthropology WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts May 19, 2019 Introduction Peru is famous for its Pre-Hispanic archaeological sites: places like Machu Picchu, the Nazca lines, and the city of Chan Chan. Ranging from the earliest cities in the Americas to Inca metropolises, millennia of urban human history along the Andes have left large and striking sites scattered across the country. But cities and monuments do not exist in solitude. Peru’s ancient sites are connected by a vast circulatory system of roads that connected every corner of the country, and thousands of square miles beyond its current borders. The Inca road system, or Qhapaq Ñan, is particularly famous; thousands of miles of trails linked the empire from modern- day Colombia to central Chile, crossing some of the world’s tallest mountain ranges and driest deserts. The Inca state recognized the importance of its road system, and dotted the trails with rest stops, granaries, and religious shrines. Inca roads even served directly religious purposes in pilgrimages and a system of ritual pathways that divided the empire (Ogburn 2010). This project contributes to scholarly knowledge about the Inca and Pre-Hispanic Andean civilizations by studying the roads which stitched together the Inca state. -

Environments

EXTREME Environments Deborah Underwood EXTREME Environments Deborah Underwood Contents A World of Extremes 2 Chapter 1: The Coolest Places on Earth 4 Chapter 2: The Driest Desert 16 Chapter 3: Hot Spots 20 Chapter 4: Water, Water Everywhere 28 Chapter 5: The World’s Worst Climate? 36 Chapter 6: Under the Sea 42 Index 48 A World of Extremes Imagine a mountaintop where plumes of ice grow at the rate of one foot every hour, where you can watch a beautiful ice sculpture form over the course of one day. What about a desert where decades pass without rain, and the ground is dry and cracked in a thousand different places. How could anything possibly live there? Imagine winds that gust at speeds of 200 miles per hour. Could you survive out in the open with such winds blasting against you? How about temperatures of more than 130° Fahrenheit? What’s it like trying to survive in such harsh environments? 2 Now try to imagine a place that has never seen the sun’s rays. This is a place where there is nothing but darkness all day, all year round. What sort of creature could live there? Would it look like anything you’ve ever seen before? In this book we’ll visit some of Earth’s most extreme climates. We’ll see why these climates are so difficult to live in, and we’ll also check out some of the amazing creatures that call these places their homes. So grab a heavy coat, some sunscreen, an umbrella, and a big water bottle—we need to be ready for anything! 3 Chapter 1 The Coolest Places on Earth Got your parka zipped up and your gloves on? Good, because the first stop on our extreme climate tour will be one of the coldest places in the world. -

The Impact of ENSO in the Atacama Desert and Australian Arid Zone: Exploratory Time-Series Analysis of Archaeological Records

Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena ISSN: 0716-1182 [email protected] Universidad de Tarapacá Chile Williams, Alan; Santoro, Calogero M.; Smith, Michael A.; Latorre, Claudio The impact of ENSO in the Atacama desert and Australian arid zone: exploratory time-series analysis of archaeological records Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena, vol. 40, 2008, pp. 245-259 Universidad de Tarapacá Arica, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=32609903 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative The impact of ENSO in the Atacama Desert and Australian arid zone:Volumen Exploratory 40 Número time-series Especial, analysis… 2008. Páginas 245-259245 Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena THE IMPACT OF ENSO IN THE ATACAMA DESERT AND AUSTRALIAN ARID ZONE: EXPLORATORY TIME-SERIES ANALYSIS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORDS1 EL IMPACTO DE ENSO EN EL DESIERTO DE ATACAMA Y LA ZONA ÁRIDA DE AUSTRALIA: ANÁLISIS EXPLORATORIOS DE SERIES TEMPORALES ARQUEOLÓGICAS Alan Williams2, Calogero M. Santoro3, Michael A. Smith4, and Claudio Latorre5 A comparison of archaeological data in the Atacama Desert and Australian arid zone shows the impact of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) over the last 5,000 years. Using a dataset of > 1400 radiocarbon dates from archaeological sites across the two regions as a proxy for population change, we develop radiocarbon density plots, which are then used to explore the responses of these prehistoric populations to ENSO climatic variability. -

Brazil Eyes the Peruvian Amazon

Site of the proposed Inambari Dam in the Peruvian Amazon. Brazil Eyes the Photo: Nathan Lujan Peruvian Amazon WILD RIVERS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AT RISK he Peruvian Amazon is a treasure trove of biodiversity. Its aquatic ecosystems sustain Tbountiful fisheries, diverse wildlife, and the livelihoods of tens of thousands of people. White-water rivers flowing from the Andes provide rich sediments and nutrients to the Amazon mainstream. But this naturally wealthy landscape faces an ominous threat. Brazil’s emergence as a regional powerhouse has been accom- BRAZIL’S ROLE IN PERU’S AMAZON DAMS panied by an expansionist energy policy and it is looking to its In June 2010, the Brazilian and Peruvian governments signed neighbors to help fuel its growth. The Brazilian government an energy agreement that opens the door for Brazilian com- plans to build more than 60 dams in the Brazilian, Peruvian panies to build a series of large dams in the Peruvian Amazon. and Bolivian Amazon over the next two decades. These dams The energy produced is largely intended for export to Brazil. would destroy huge areas of rainforest through direct flood- The first five dams – Inambari, Pakitzapango, Tambo 40, ing and by opening up remote forest areas to logging, cattle Tambo 60 and Mainique – would cost around US$16 billion, ranching, mining, land speculation, poaching and planta- and financing is anticipated to come from the Brazilian National tions. Many of the planned dams will infringe on national Development Bank (BNDES). parks, wildlife sanctuaries and some of the largest remaining wilderness areas in the Amazon Basin. -

La Cosmología En El Dibujo Del Altar Del Quri Kancha Según Don Joan

La cosmología en el dibujo del altar del Quri Kancha según don Joan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salca Maygua Rita Fink Se suele adscribir al dibujo del altar de Quri Kancha una estructura bipartita (dos campos separados por un eje vertical), la cual refleja la oposición andina de hanan-hurin o alternativamente la simetría de los altares eclesiásticos. El presente trabajo identifica los elementos del dibujo y analiza las parejas que ellos componen, examinando el simbolismo de cada una de ellas y las interrelaciones de sus componentes en varias fuentes de los siglos XVI-XX. El mundo dibujado está organizado según el principio andino de hanan-hurin aplicado en dos dimensiones, la horizontal y la vertical. Dos ejes, hanan y hurin, dividen el espacio en cuatro campos distintos. Los campos inferiores están organizados de manera inversa con respecto al espacio superior. Semejantes estructuras cuatripartitas se encuentran en otras representaciones espacio-temporales andinas. The structure of the drawing of the Quri Kancha altar has been described as dual, reflecting either the Andean hanan-hurin complementarity or the symmetry of Christian church altars. Present study identifies the elements presented in the drawing and analyses the couples which they comprise, demonstrating the symbolism of each couple and the hanan-hurin relations within them, as evident in XVI-XX century sources. The world presented in the drawing of the Quri Kancha altar is organized according to the Andean hanan-hurin principle applied on two-dimensional scale (horizontal and vertical). Two axes - hanan and hurin - divide the space into 4 distinct fields. The lower fields are inverted relative to the hanan space above. -

The Spanish Unraveling of the Incan Empire: the Importance of Fibers and Textiles of the Past

University of Wisconsin–Superior McNair Scholars Journal, volume 2, 2001 The Spanish Unraveling Of the Incan Empire: The Importance of Fibers and Textiles of the Past Rhonda R. Dass, Art History William Morgan, M.F.A. Department of Visual Arts ABSTRACT Steeped in ancient traditions, modern day Peru can boast the continuation of cultural heritage dating back before 1000 BC. The coastal desert climate is perfect for the preservation of textiles long buried in the sacred graves of past peoples. From these artifacts we can see how important the textiles of the Incan culture were to its people. Some argue that internal strife was the main factor for the ease with which the Spaniards were able to conquer the advanced civilization of the Incas. Others argue that the empire was already in decline. Perhaps the textile– based economy of the Incan empire was the prime factor. History of the Incan Empire: Geographical and Political The area of South America, which once sustained the mighty Incan empire during the early half of the 10th millennium, is a diverse, breathtaking and often inhospitable land. As the Incans, led by Manco Capac, spread their empire across the South American continent they conquered numerous small tribes scattered throughout an awesome array of nature's wonders. They started their reign in the area surrounding Lake Titicaca, still considered a sacred place by their modern day ancestors, taking control of the local Tiwanaku peoples. From this region nestled in the Andes Mountains they battled their way across mountain ridges that draw a line down the coastal areas of South America. -

Long Term Atmospheric Deposition As the Source of Nitrate and Other Salts in the Atacama Desert, Chile

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, Vol. 68, No. 20, pp. 4023-4038, 2004 Copyright © 2004 Elsevier Ltd Pergamon Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0016-7037/04 $30.00 ϩ .00 doi:10.1016/j.gca.2004.04.009 Long term atmospheric deposition as the source of nitrate and other salts in the Atacama Desert, Chile: New evidence from mass-independent oxygen isotopic compositions 1, 2 1 GREG MICHALSKI, *J.K.BÖHLKE and MARK THIEMENS 1Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0356, USA 2United States Geological Survey, 431 National Center, Reston, VA 20192, USA (Received August 19, 2003; accepted in revised form April 7, 2004) Abstract—Isotopic analysis of nitrate and sulfate minerals from the nitrate ore fields of the Atacama Desert in northern Chile has shown anomalous 17O enrichments in both minerals. ⌬17O values of 14–21 ‰ in nitrate and0.4to4‰insulfate are the most positive found in terrestrial minerals to date. Modeling of atmospheric processes indicates that the ⌬17O signatures are the result of photochemical reactions in the troposphere and stratosphere. We conclude that the bulk of the nitrate, sulfate and other soluble salts in some parts of the Atacama Desert must be the result of atmospheric deposition of particles produced by gas to particle conversion, with minor but varying amounts from sea spray and local terrestrial sources. Flux calculations indicate that the major salt deposits could have accumulated from atmospheric deposition in a period of 200,000 to 2.0 M years during hyper-arid conditions similar to those currently found in the Atacama Desert. -

Ncomms8100.Pdf

ARTICLE Received 14 Jul 2014 | Accepted 1 Apr 2015 | Published 11 May 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8100 Evidence for photochemical production of reactive oxygen species in desert soils Christos D. Georgiou1, Henry J. Sun2, Christopher P. McKay3, Konstantinos Grintzalis1, Ioannis Papapostolou1, Dimitrios Zisimopoulos1, Konstantinos Panagiotidis1, Gaosen Zhang4, Eleni Koutsopoulou5, George E. Christidis6 & Irene Margiolaki1 The combination of intense solar radiation and soil desiccation creates a short circuit in the biogeochemical carbon cycle, where soils release significant amounts of CO2 and reactive nitrogen oxides by abiotic oxidation. Here we show that desert soils accumulate metal superoxides and peroxides at higher levels than non-desert soils. We also show the photo- generation of equimolar superoxide and hydroxyl radical in desiccated and aqueous soils, respectively, by a photo-induced electron transfer mechanism supported by their mineralogical composition. Reactivity of desert soils is further supported by the generation of hydroxyl radical via aqueous extracts in the dark. Our findings extend to desert soils the photogeneration of reactive oxygen species by certain mineral oxides and also explain previous studies on desert soil organic oxidant chemistry and microbiology. Similar processes driven by ultraviolet radiation may be operating in the surface soils on Mars. 1 Department of Biology, University of Patras, Patras 26504, Greece. 2 Desert Research Institute, Las Vegas, Nevada 89119, USA. 3 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California 94035, USA. 4 Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 73000, China. 5 Laboratory of Electron Microscopy and Microanalysis, University of Patras, Patras 26500, Greece. 6 Department of Mineral Resources Engineering, Technical University of Crete, Chania 73100, Greece. -

Atmospheric Deposition Across the Atacama Desert, Chile Compositions, Source Distributions, and Interannual Comparisons

Chemical Geology 525 (2019) 435–446 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Chemical Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/chemgeo Atmospheric deposition across the Atacama Desert, Chile: Compositions, source distributions, and interannual comparisons T ⁎ Jianghanyang Lia, Fan Wangb,c, , Greg Michalskia,d, Benjamin Wilkinsd a Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA b School of Atmospheric Sciences, Guangdong Province Key Laboratory for Climate Change and Natural Disaster Studies, Sun Yat-sen University, Zhuhai 519082, China c Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai), Zhuhai 519082, China d Department of Chemistry, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Editor: Donald Porcelli Hyper-arid areas such as the Atacama Desert accumulated significant amounts of insoluble dust and soluble salts Keywords: from the atmosphere, providing minable salt deposits as well as mimicking the surface processes on Mars. The Atacama Desert deposition rates, compositions and sources, however, were poorly constrained. Especially, the variabilities of Atmospheric deposition atmospheric deposition in the Atacama Desert corresponding to a changing climate were unassessed. In this Interannual comparison work, the atmospheric depositions collected using dust traps across a west-east elevation gradient in the Sulfur isotopes Atacama (~23°S) from 1/2/2010 to 12/31/2011 were analyzed and compared to previous results in 2007–2009. The insoluble dust deposition rates in our sampling period were significantly higher than those of 2007–2009 in most dust traps, which was attributed to the changes in wind, highlighting the importance of long-term mon- itoring of insoluble dust fluxes.