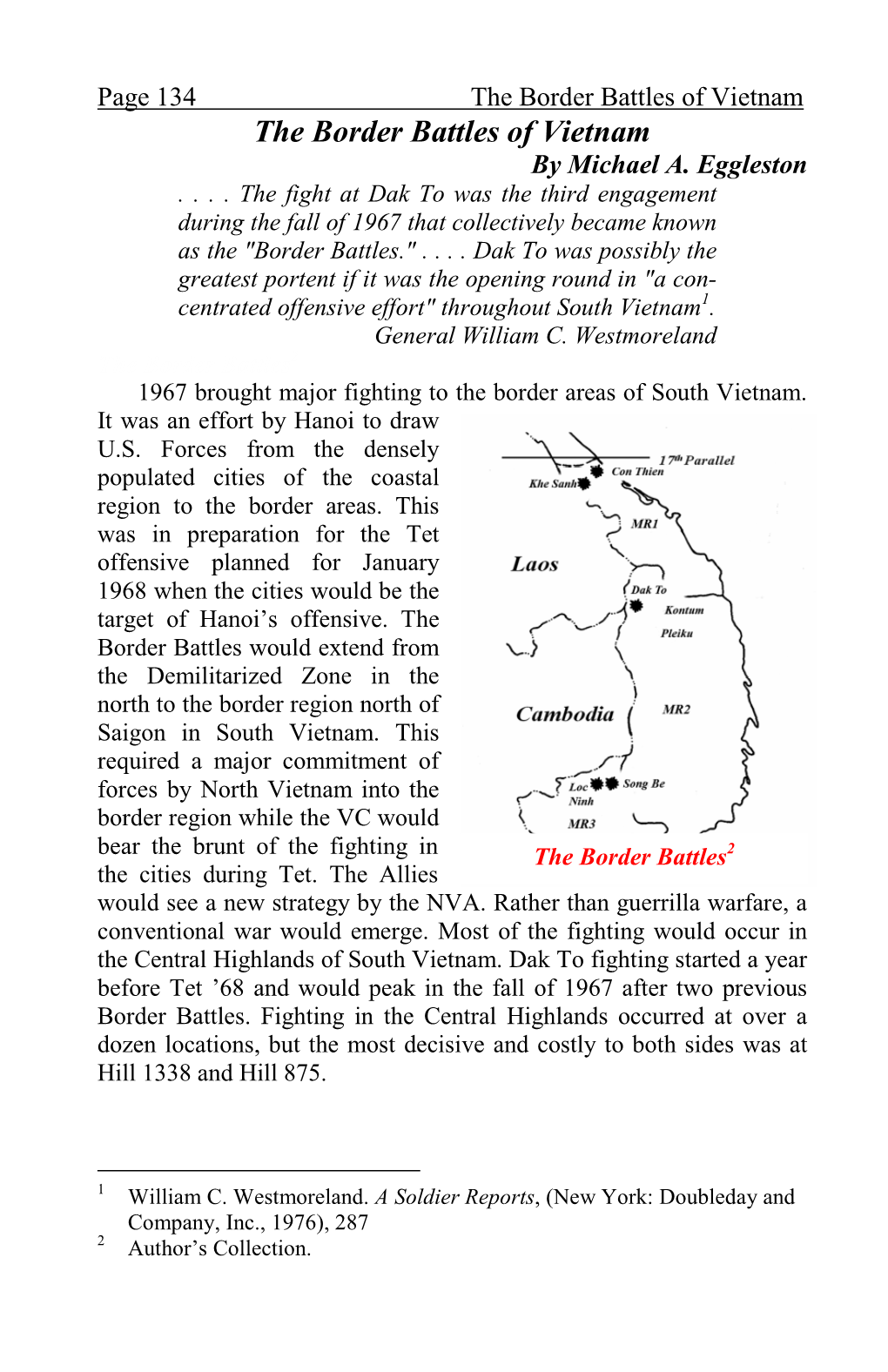

The Border Battles of Vietnam the Border Battles of Vietnam by Michael A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Marine Corps Vietnam War

by Leslie Mount for the City of Del City 9th Edition, November 2018 View online or leave a comment at www.cityofdelcity.com The Armistice of World War I On a street in Sarajevo on the sunny morning of June 28, 1914, a Serbian nationalist, 19 year old Gavrilo Princip, fired two shots into Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand's car, killing both the heir to the Hapsburg throne and his wife Sophie. The two shots “heard ‘round the world” set in motion the events that led to World War I. A remarkable series of events known as the treaty alliance system led to the scale of “The Great War.” European nations mobilized and declared war on other nations in a tangled web of alliances, some of which dated back to Bismarck and the unification of Germany in the late 1800’s. Europe was divided between the Allied Forces (Britain, France, Russia, the Serbian Kingdom, and later joined by Italy), and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria- Hungary and the Ottoman Empire) Europe entered the war in 1914. On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany following Germany’s sinking of the neutral British ocean liner the RMS Lusitania that carried mostly passengers, including 159 Americans; and the 1917 Zimmermann Telegram in which Germany sent a coded message to Mexico offering United States’ lands to Mexico in return for Mexico joining World War I against the United States. The First World War was an extremely bloody war that was fought mainly in trenches and employed modern weaponry unlike any that had been used before. -

Issue 41 Contact: [email protected]

June 2012, Issue 41 Contact: [email protected] See all issues to date at the 503rd Heritage Battalion web site: http://corregidor.org/VN2-503/newsletter/issue_index.htm _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ~ 2/503d Photo of the Month ~ 335th AHC Cowboys delivering their cargo of 2/503d troopers into the rice paddies of SVN. (Photo by Door-Gunner John Cavinee, Cowboys, cousin of Ron Cavinee, A/2/503d, KIA) 2/503d VIETNAM Newsletter / June 2012 – Issue 41 Page 1 of 60 that the criticism that pastors face was countered and that Chaplain’s Corner his needs were being shared, met, and overcome. The next Sunday, the Pastor stood up behind the podium as church started and on the podium were a stack of notes- "I Got Your 6" each saying..."Pastor, I got your 6 covered.” They were praying for him and guarding him, so to speak, and they were part of his team. his is my second opportunity to share Just maybe the Lord has a call on your life to reach out with you, and I'm and help someone else. I believe He has a mission for glad that you are you and me. Even as you read this message, and T back! Let me regardless where we might be....God has a purpose for review, just a moment, where us right now, right where you are, and no matter who we were and where we you and I are. Whatever we might have encountered in finished last month. The our past or what's in our future, He has permitted us to Scripture I used was from Cap be in this place and time for a specific reason.. -

La Diáspora Puertorriqueña: Un Legado De Compromiso the Puerto Rican Diaspora: a Legacy of Commitment

Original drawing for the Puerto Rican Family Monument, Hartford, CT. Jose Buscaglia Guillermety, pen and ink, 30 X 30, 1999. La Diáspora Puertorriqueña: Un Legado de Compromiso The Puerto Rican Diaspora: A Legacy of Commitment P uerto R ican H eritage M o n t h N ovember 2014 CALENDAR JOURNAL ASPIRA of NY ■ Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños ■ El Museo del Barrio ■ El Puente Eugenio María de Hostos Community College, CUNY ■ Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly La Casa de la Herencia Cultural Puertorriqueña ■ La Fundación Nacional para la Cultura Popular, PR LatinoJustice – PRLDEF ■ Música de Camara ■ National Institute for Latino Policy National Conference of Puerto Rican Women – NACOPRW National Congress for Puerto Rican Rights – Justice Committee Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration www.comitenoviembre.org *with Colgate® Optic White® Toothpaste, Mouthwash, and Toothbrush + Whitening Pen, use as directed. Use Mouthwash prior to Optic White® Whitening Pen. For best results, continue routine as directed. COMITÉ NOVIEMBRE Would Like To Extend Is Sincerest Gratitude To The Sponsors And Supporters Of Puerto Rican Heritage Month 2014 City University of New York Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly Colgate-Palmolive Company Puerto Rico Convention Bureau The Nieves Gunn Charitable Fund Embassy Suites Hotel & Casino, Isla Verde, PR Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center American Airlines John Calderon Rums of Puerto Rico United Federation of Teachers Hotel la Concha Compañia de Turismo de Puerto Rico Hotel Copamarina Acacia Network Omni Hotels & Resorts Carlos D. Nazario, Jr. Banco Popular de Puerto Rico Dolores Batista Shape Magazine Hostos Community College, CUNY MEMBER AGENCIES ASPIRA of New York Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños El Museo del Barrio El Puente Eugenio María de Hostos Community College/CUNY Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly La Casa de la Herencia Cultural Puertorriqueña, Inc. -

2/503 Photo of the Month ~

October 2012, Issue 46 Contact: [email protected] See all issues to date at the 503rd Heritage Battalion website: http://corregidor.org/VN2-503/newsletter/issue_index.htm _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ~ 2/503 Photo of the Month ~ The Aftermath C/2/503 troopers taking care of their buddies, circa ’66/’67. Photo by Jack Leide, CO C/2/503d. 2/503d VIETNAM Newsletter / October 2012 – Issue 46 Page 1 of 60 Boats could not be used and a helicopter was called, but Chaplain’s Corner its chance of success was not good, as the whipping snowstorm would be risky, just as it was when it brought the airplane down. Nevertheless, twenty minutes after He Died For Us the crash and as the sun was going down a rescue chopper came. One victim was hoisted out, and then as Once more into the battle…it was St. the cable was lowered again something miraculous Crispen’s Day - the year 1415. We’re happened. The man who grabbed it, passed it on to in France near Agincourt. The two “Cap” another who was hauled out. Again the cable was enemies, France and England, face one lowered and the man passed it on to another who was another, and exchanging taunts designed to provoke an lifted out. Again the same thing happened. As the attack. King Henry marches his force close enough to chopper seconds later wheeled to again drop the cable, allow his archers to unleash a hail of arrows upon the the man had vanished beneath the icy water. Who was French. The French knights charged forward only to be he? Arland Dean Williams, Jr. -

Dak TO.Pages

RED WARRIORS VIETNAM ASSOCIATION SPECIAL ARTICLE RED WARRIORS Violent Clash At Dak To HILL 875 Tim Dyhouse Hill 875 was one of the costliest battles in the entire Senior Editor, VFW magazine Vietnam War. The battle, VFW National Headquarters just one element of the enemy’s o"ensive on Dak To, Reprinted with permission. pitted the determined NVA VFW magazine, November/December 2017 against the will of American FIFTY YEARS AGO THIS MONTH, THE 173RD AIRBORNE forces. BRIGADE AND THE 4TH INFANTRY DIVISION’S 1ST BRIGADE Mainly an operation of SLUGGED IT OUT WITH FOUR NVA REGIMENTS IN THE the 173rd Airborne, the 4th CENTRAL HIGHLANDS. THE CENTERPIECE OF THE BATTLE Division was called in to WAS THE 110-HOUR FIGHT FOR HILL 875. assist and the Red Warriors saw action during the final In November 1967, North 3rd battalions of the 8th Inf. Regt.; days and final assault of the Vietnamese Army (NVA) units were 1st and 3rd battalions of the 12th hill in this historical battle. determined to rid the Central Inf. Regt.; and the attached 2nd Highlands of American forces. The Sqdn., 1st Cav Regt. VFW Magazine Senior NVA poured thousands of troops Editor tim Dyhouse dissects into an area where the borders of The 173rd Airborne Brigade fielded the battle in his November Cambodia, Laos and South Vietnam the 1st, 2nd and 4th battalions of the 2017 article published in meet. 503rd Inf. Regt., and supporting VFW Magazine. units such as the 335th Aviation Specifically, they sought to destroy Company. Special Forces camps at Ben Het, about five miles east of the Some 15 Army artillery batteries Cambodian border, and at Dak To, along with tactical air support some 10 miles east of Ben Het. -

Labadie, Jr. October 8, 1958 – April 7, 2004 SFC – Army

Compiled, designed and edited by Leslie Mount for the City of Del City 6th Edition, November 2015 View online or leave a comment at www.cityofdelcity.com If you have any information about the heroes on these pages, please contact Leslie Mount City of Del City 3701 S.E. 15th Street Del City, OK 73115 (405) 670-7302 [email protected] Billy A. Krowse December 14, 1925 – March 13, 1945 PFC – US Army World War II illy attended the Oklahoma Military ably reorganized the remnants of the unit, and B Academy in Claremore, Oklahoma. He issued orders for a continued assault. Observing had completed a year of college before enlisting a hostile machine gun position holding up fur- in the Army on March 25, 1944, for a term of ther advance, he proceeded alone under fire and the duration of the war plus six months. Billy succeeded in personally eliminating the enemy was proud to serve his country, and his goal was position. While clearing the area around the to attend Officer Candidate School. gun position, he was killed by a hidden enemy rifleman, but his indomitable courage so Billy was posthumously awarded inspired his comrades that they surged forward the Distinguished Service Cross and secured the hill. The consummate for “… extraordinary heroism determination, exemplary leadership, and heroic in connection with military self-sacrifice, clearly displayed by Private operations against an armed Krowse reflect the highest credit upon himself, enemy while serving with the 78th Infantry Division, and the United States Company G, 311th Infantry Army.” [Department of the Army, General Regiment, 78th Infantry Division, Orders No. -

Congressional Record—Senate S4605

June 28, 2016 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S4605 Thereupon, the Senate, at 12:45 p.m., up raises for, benefits they have domestic energy in our backyard. Do- recessed until 2:15 p.m. and reassem- earned, putting money aside, and now mestic energy was the coal we used to bled when called to order by the Pre- they have been betrayed, frankly, and fuel the Industrial Revolution. We basi- siding Officer (Mrs. CAPITO). that is why this is so important. cally defended ourselves in every war f We just had a meeting of a group of with coal. It was so important during Senators, and Senator REID played a World War II that if you were a coal TRANSPORTATION, HOUSING AND film of what is happening in West Vir- miner, you would be asked to be de- URBAN DEVELOPMENT, AND RE- ginia—the flooding—and much of that ferred from fighting in the war to pro- LATED AGENCIES APPROPRIA- flooding is in miners’ country, most of vide the energy the country needed to TIONS ACT, 2016—CONFERENCE it is. There were mine workers’ defend itself. That is how important REPORT—Continued homes—Senator CAPITO knows this this product has been. The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Sen- too—mine workers’ homes that were Today it is kind of taboo to talk ator from West Virginia. under water, as were other residents in about it. People don’t understand we Mr. MANCHIN. Madam President, I these communities, proud communities have the life we have because of it. ask unanimous consent to speak in a that have done everything right, where There is a transition going on and we colloquy with some of my colleagues people worked hard and played by the understand that, but, in 1946, President concerning the Miners Protection Act. -

US Offensives VIETNAM

US Offensives (Offensives and Named Campaigns) VIETNAM WAR Source: U.S. Army Center of Military History Advisory 15 March 1962 - 7 March 1965 Defense 08 March 1965 - 24 December 1965 Counteroffensive 25 December 1965 - 30 June 1966 Counteroffensive, Phase II 01 July 1966 - 31 May 1967 Counteroffensive, Phase III 01 June 1967 - 29 January 1968 Tet Counteroffensive 30 January 1968- 01 April 1968 Counteroffensive, Phase IV 02 April 1968 - 30 June 1968 Counteroffensive, Phase V 01 July 1968- 1 November 1968 Counteroffensive, Phase VI 02 November 1968 - 22 February 1969 Tet 69/Counteroffensive 23 February 1969 - 8 June 1969 Summer-Fall 1969 09 June 1969 - 31 October 1969 Winter-Spring 1970 01 November 1969 - 30 April 1970 Sanctuary Counteroffensive 01 May 1970 - 30 June 1970 Counteroffensive, Phase VII 01 July 1970 - 30 June 1971 Consolidation I 01 July 1971 - 30 November 1971 Consolidation II 01 December 1971 - 29 March 1972 Cease-Fire 30 March 1972 - 28 January 1973 Advisory, 15 March 1962 - 07 March 1965 During this period, direct U.S. involvement in the Vietnam conflict increased steadily as U.S. trained Vietnamese pilots moved Vietnamese helicopter units into and out of combat. Ultimately the United States hoped that a strong Vietnamese government would result in improved internal security and national defense. The number of U.S. advisors in the field rose from 746 in January 1962 to over 3,400 by June; the entire U.S. commitment by the end of the year was 11,000, which included 29 U.S. Army Special Forces detachments. These advisory and support elements operated under the Commander, U.S. -

A Short History of Army Intelligence

A Short History of Army Intelligence by Michael E. Bigelow, Command Historian, U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command Introduction On July 1, 2012, the Military Intelligence (MI) Branch turned fi fty years old. When it was established in 1962, it was the Army’s fi rst new branch since the Transportation Corps had been formed twenty years earlier. Today, it remains one of the youngest of the Army’s fi fteen basic branches (only Aviation and Special Forces are newer). Yet, while the MI Branch is a relatively recent addition, intelligence operations and functions in the Army stretch back to the Revolutionary War. This article will trace the development of Army Intelligence since the 18th century. This evolution was marked by a slow, but steady progress in establishing itself as a permanent and essential component of the Army and its operations. Army Intelligence in the Revolutionary War In July 1775, GEN George Washington assumed command of the newly established Continental Army near Boston, Massachusetts. Over the next eight years, he dem- onstrated a keen understanding of the importance of MI. Facing British forces that usually outmatched and often outnumbered his own, Washington needed good intelligence to exploit any weaknesses of his adversary while masking those of his own army. With intelligence so imperative to his army’s success, Washington acted as his own chief of intelligence and personally scrutinized the information that came into his headquarters. To gather information about the enemy, the American com- mander depended on the traditional intelligence sources avail- able in the 18th century: scouts and spies. -

173D Photo of the Month ~

November-December 2017, Issue 76 See all issues to date at 503rd Heritage Battalion website: Contact: [email protected] http://corregidor.org/VN2-503/newsletter/issue_index.htm ~ 173d Photo of the Month ~ Father Roy Peters conducts services for Sky Soldiers at Dak To in the jungle battlefield of Vietnam before next assault up Hill 875, in November 1967. See more about Fr Peters on Pages 45-47. Photo courtesy of June Peters 2/503d VIETNAM Newsletter / Nov.-Dec. 2017 – Issue 76 Page 1 of 88 We Dedicate this Issue of Our Newsletter in Memory and Honor of the Men of the 173d Airborne Brigade & Attached Units We Lost 50 Years Ago in the Months of November & December 1967 "It is, in a way, an odd thing to honor those who died in defense of our country, in defense of us, in wars far away. The imagination plays a trick. We see these soldiers in our mind as old and wise. We see them as something like the Founding Fathers, grave and gray haired. But most of them were boys when they died, and they gave up two lives -- the one they were living and the one they would have lived. When they died, they gave up their chance to be husbands and fathers and grandfathers. They gave up their chance to be revered old men. They gave up everything for our country, for us. And all we can do is remember." Commander in Chief Ronald Reagan, at dedication of Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC Clarence Mattue Adams, 25 Louis George Washi Arnold, 19 SSG, A/3/503, 12/30/67 PFC, A/2/503, 11/20/67 “Thank you Staff Sergeant Adams for (Virtual Wall states A/4/503) your devotion, leadership, and courage.” “Buddy. -

List of Hispanic Medal of Honor Recipients 1 List of Hispanic Medal of Honor Recipients

List of Hispanic Medal of Honor recipients 1 List of Hispanic Medal of Honor recipients The Medal of Honor was created during the American Civil War and is the highest military decoration presented by the United States government to a member of its armed forces. The recipient must have distinguished themselves at the risk of their own life above and beyond the call of duty in action against an enemy of the United States. Due to the nature of this medal, it is commonly presented posthumously.[1] Forty-three men of Hispanic heritage have been awarded the Medal of Honor. Of the forty-three Medals of Honor presented to Hispanics, two were presented to members of the United States Navy, thirteen to members of the United States Marine Corps and twenty-eight to members of the United States Army. Twenty-five Medals of Honor were presented posthumously.[2] The first recipient was Corporal Joseph H. De Castro of the Union Army for Reverse of the Medal of Honor awarded his actions at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on July 3, 1863, during the American to Seaman John Ortega Civil War and the most recent recipient was Captain Humbert Roque Versace who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor on July 8, 2002, by President George W. Bush. Corporal De Castro was a member of the Massachusetts Infantry, a militia that was not part of the "regular" army; however, Private David Bennes Barkley was a member of the regular army during World War I and has been recognized as the Army's first Hispanic Medal of Honor recipient.[3] In 1864, Seaman John Ortega became the first Hispanic member of the U.S. -

Table of Contents List of Figures

Table of Contents List of Figures ........................................................................................................................ 6 Section 1: Plan Summary ....................................................................................................... 1 Section 2: Introduction ......................................................................................................... 2 2A. Statement of Purpose ..............................................................................................................2 2B. Planning Process and Public Participation ................................................................................3 2C. Enhanced Outreach and Public Participation ............................................................................5 Section 3: Community Setting ................................................................................................ 6 3A. Regional Context .....................................................................................................................6 3A.1 Regional Governance ................................................................................................................................ 6 3A.2 Surrounding Communities ........................................................................................................................ 8 3A.3 Natural Setting .......................................................................................................................................... 8 3A.4 Transportation