The Natural Resource Curse in Xinjiang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Security and the Causes of Violent Uighur Separatism

Griffith Asia Institute Regional Outlook China’s ‘War on Terror’ in Xinjiang: Human Security and the Causes of Violent Uighur Separatism Michael Clarke Regional Outlook i China’s ‘War on Terror’ in Xinjiang About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute produces innovative, interdisciplinary research on key developments in the politics, economics, societies and cultures of Asia and the South Pacific. By promoting knowledge of Australia’s changing region and its importance to our future, the Griffith Asia Institute seeks to inform and foster academic scholarship, public awareness and considered and responsive policy making. The Institute’s work builds on a 32 year Griffith University tradition of providing cutting- edge research on issues of contemporary significance in the region. Griffith was the first University in the country to offer Asian Studies to undergraduate students and remains a pioneer in this field. This strong history means that today’s Institute can draw on the expertise of some 50 Asia-Pacific focused academics from many disciplines across the university. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Regional Outlook’ papers publish the institute’s cutting edge, policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asiainstitute ‘China’s “War on Terror” in Xinjiang: Human Security and the Causes of Violent Uighur Separatism’, Regional Outlook Paper No. 11, 2007. About the Author Michael Clarke Michael Clarke recently received his doctorate from Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia. His dissertation entitled ‘In the Eye of Power: China and Xinjiang from the Qing Conquest to the ‘New Great Game’ for Central Asia, 1759-2004’ examined the expansion of Chinese state power in the ‘Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region’ since the 18th century and the implications of this complex process for China’s foreign policy in Central Asia. -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

“Kashgar City Circle” Industry Development in the Contest of the Silk Road Economic Belt

E3S Web of Conferences 235, 02023 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123502023 NETID 2020 A Study on “Kashgar City Circle” Industry Development in the Contest of the Silk Road Economic Belt Pan Jie1,a, Bai Xiao*2,b(Corresponding Author) 1 Faculty of Transportation and Management, Xinjiang Vocational and Technical College of Communications, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China 2 Postdoctoral Innovation Practice Base, Xinjiang Vocational and Technical College of Communications, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China Abstract. Kashgar City Circle is an important node of the new The Silk Road economic belt.Kashgar City Circle will serve as a new economic growth pole in the western region and will promote the rapid development of regional economy.The development of industry is an important driving force for regional economic development.This paper analyzes the four indicators of total output value,output value growth rate,employed population and labor productivity of the 18 industrial sectors of Kashgar City Circle from 2012 to 2016.Combined with the opportunities brought by the Silk Road economic belt background to the development of the Kashgar City Circle industry,this paper puts forward the current policy recommendations for the development of the Kashgar City Circle industry. research on the adjustment and optimization of industrial 1 Introduction structure [6-10],the current economic development situation[11-12],the impact of fixed asset investment on Kashgar is the traffic hub of the ancient The Silk Road, the industrial structure change[13-14].However, based on the traffic hub of the new The Silk Road economic belt, and a background of The Silk Road economic belt, there are major channel for trade with neighboring countries. -

Molecular Analysis of the Genetic Diversity of Chinese Hami Melon and Its Relationship to the Melon Germplasm from Central and South Asia

J. Japan. Soc. Hort. Sci. 80 (1): 52–65. 2011. Available online at www.jstage.jst.go.jp/browse/jjshs1 JSHS © 2011 Molecular Analysis of the Genetic Diversity of Chinese Hami Melon and Its Relationship to the Melon Germplasm from Central and South Asia Yasheng Aierken1,2, Yukari Akashi1, Phan Thi Phuong Nhi1, Yikeremu Halidan1, Katsunori Tanaka3, Bo Long4, Hidetaka Nishida1, Chunlin Long4, Min Zhu Wu2 and Kenji Kato1* 1Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Okayama University, Okayama 700-8530, Japan 2Hami Melon Research Center, Xinjiang Academy of Agricultural Science, Urumuqi 830000, China 3Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto 603-8047, Japan 4Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS, Heilongtan, Kunming, Yunnan 650204, China Chinese Hami melon consists of the varieties cassaba, chandalak, ameri, and zard. To show their genetic diversity, 120 melon accessions, including 24 accessions of Hami melon, were analyzed using molecular markers of nuclear and cytoplasmic genomes. All Hami melon accessions were classified as the large-seed type with seed length longer than 9 mm, like US and Spanish Inodorus melon. Conomon accessions grown in east China were all the small- seed type. Both large- and small-seed types were in landraces from Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia. Analysis of an SNP in the PS-ID region (Rpl16-Rpl14) and size polymorphism of ccSSR7 showed that the melon accessions consisted of three chloroplast genome types, that is, maternal lineages. Hami melon accessions were T/338 bp type, which differed from Spanish melon and US Honey Dew (T/333 bp type), indicating a different maternal lineage within group Inodorus. -

China's Campaign to Open the West: Xinjiang and the Center by Robert

China’s Campaign to Open the West: Xinjiang and the Center by Robert Vaughn Moeller BS in International Affairs, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Graduate School of Arts and Sciences This thesis was presented by Robert Vaughn Moeller It was defended on November 21, 2006 and approved by Thomas Rawski, PhD, Professor, Economics Evelyn Rawski, PhD, Professor, History Katherine Carlitz, PhD, Adjunct Professor, East Asian Languages and Literature Thesis Director: Thomas Rawski, PhD, Professor, Economics ii China’s Campaign to Open the West: Xinjiang and the Center Robert Vaughn Moeller, M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This paper examines China’s ambitious Campaign to Open the West and its impact upon Han and ethnic minority populations in Xinjiang. It focuses on analyzing the components of the campaign that are being implemented to develop Xinjiang through the intensification of agriculture, exploitation of energy resources, and reforms to Xinjiang’s education system, revealing that the campaign, rather than alleviating poverty, is leading to greater asymmetry between Han and ethnic minority populations within Xinjiang. Rather than a plan for bridging the gap of economic disparity between the eastern and western regions of China, as construed by Beijing, the plan fits into a greater strategy for integration and assimilation of Xinjiang’s restive ethnic population by Beijing. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 2.0 THE PLAN IN CONTEXT ......................................................................................... 4 3.0 DEFINING THE WEST............................................................................................. -

Violent Resistance in Xinjiang (China): Tracking Militancy, Ethnic Riots and ‘Knife- Wielding’ Terrorists (1978-2012)

HAO, Núm. 30 (Invierno, 2013), 135-149 ISSN 1696-2060 VIOLENT RESISTANCE IN XINJIANG (CHINA): TRACKING MILITANCY, ETHNIC RIOTS AND ‘KNIFE- WIELDING’ TERRORISTS (1978-2012) Pablo Adriano Rodríguez1 1University of Warwick (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Recibido: 14 Octubre 2012 / Revisado: 5 Noviembre 2012 / Aceptado: 10 Enero 2013 / Publicación Online: 15 Febrero 2013 Resumen: Este artículo aborda la evolución The stability of Xinjiang, the northwestern ‘New de la resistencia violenta al régimen chino Frontier’ annexed to China under the Qing 2 en la Región Autónoma Uigur de Xinjiang dynasty and home of the Uyghur people –who mediante una revisión y análisis de la officially account for the 45% of the population naturaleza de los principales episodios in the region- is one of the pivotal targets of this expenditure focused nationwide on social unrest, violentos, en su mayoría con connotaciones but specifically aimed at crushing separatism in separatistas, que han tenido lugar allí desde this Muslim region, considered one of China’s el comienzo de la era de reforma y apertura “core interests” by the government3. chinas (1978-2012). En este sentido, sostiene que la resistencia violenta, no In Yecheng, attackers were blamed as necesariamente con motivaciones político- “terrorists” by Chinese officials and media. separatistas, ha estado presente en Xinjiang ‘Extremism, separatism and terrorism’ -as en la forma de insurgencia de baja escala, defined by the rhetoric of the Shanghai revueltas étnicas y terrorismo, y Cooperation Organization (SCO)- were invoked probablemente continúe en el futuro again as ‘evil forces’ present in Xinjiang. teniendo en cuenta las fricciones existentes Countering the Chinese official account of the events, the World Uyghur Congress (WUC), a entre la minoría étnica Uigur y las políticas Uyghur organization in the diaspora, denied the llevadas a cabo por el gobierno chino. -

Sacred Right Defiled: China’S Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom

Sacred Right Defiled: China’s Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom A Report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project Table of Contents Executive Summary...........................................................................................................2 Methodology.......................................................................................................................5 Background ........................................................................................................................6 Features of Uyghur Islam ........................................................................................6 Religious History.....................................................................................................7 History of Religious Persecution under the CCP since 1949 ..................................9 Religious Administration and Regulations....................................................................13 Religious Administration in the People’s Republic of China................................13 National and Regional Regulations to 2005..........................................................14 National Regulations since 2005 ...........................................................................16 Regional Regulations since 2005 ..........................................................................19 Crackdown on “Three Evil Forces”—Terrorism, Separatism and Religious Extremism..............................................................................................................23 -

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Schluessel, Eric T. 2016. The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493602 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 A dissertation presented by Eric Tanner Schluessel to The Committee on History and East Asian Languages in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History and East Asian Languages Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April, 2016 © 2016 – Eric Schluessel All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Mark C. Elliott Eric Tanner Schluessel The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 Abstract This dissertation concerns the ways in which a Chinese civilizing project intervened powerfully in cultural and social change in the Muslim-majority region of Xinjiang from the 1870s through the 1930s. I demonstrate that the efforts of officials following an ideology of domination and transformation rooted in the Chinese Classics changed the ways that people associated with each other and defined themselves and how Muslims understood their place in history and in global space. -

Program 1-D Eclipse-City Along China's Ancient Silk Road From

Program 1-D: Page 1 of 18 Eclipse-City along China’s Silk Road in the Xinjiang Province Program 1-D Eclipse-City along China’s Ancient Silk Road From Kashgar to Hami Eclipse-City is happy to announce its extended China eclipse-program. Our extended 2008 eclipse program for China will take you primarily to China’s Northwestern Uyghur Autonomous Province of Xinjiang. Xinjiang is the largest political subdivision of China - it accounts for more than one sixth of China's total territory, a quarter of its boundary length, but only 1.5% of its total population. It is divided into two basins by the Tianshan Mountain range. Dzungarian Basin is in the north, and Tarim Basin is in the south. Xinjiang's lowest point is located in the Turfan Depression, 155 meters below sea level (second lowest in the world). Its highest peak, K2, the second highest mountain in the world, is 8,611 meters above sea level, at the border with Pakistan. This tour, based around our core program (1A), emphasizes even more the historical richness of the Silk Road in the Xinjiang province. We will travel some 2,000 km by comfortable tourist coach busses along China’s Silk Road and experience unforgettable highlights, such as the view of crystal clear high altitude lakes surrounded by snow-caped mountains, drive along the world’s second lowest point in Turpan Basin, visit ancient caves with Buddhist paintings, shop in multi-ethnic bazaars, witness stunning sand dunes, watch and/or ride the famous Barkol horse or camels and of course, enjoy more than 2 minutes of totality in our specially built camp in the Gobi Desert. -

China COI Compilation-March 2014

China COI Compilation March 2014 ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation China COI Compilation March 2014 This COI compilation does not cover the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau, nor does it cover Taiwan. The decision to exclude Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan was made on the basis of practical considerations; no inferences should be drawn from this decision regarding the status of Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan. This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared on the basis of publicly available information, studies and commentaries within a specified time frame. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. -

DC: PRC: Xinjiang Altay Urban Infrastructure and Environment

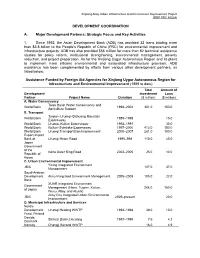

Xinjiang Altay Urban Infrastructure and Environment Improvement Project (RRP PRC 43024) DEVELOPMENT COORDINATION A. Major Development Partners: Strategic Focus and Key Activities 1. Since 1992, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has provided 32 loans totaling more than $3.8 billion to the People's Republic of China (PRC) for environmental improvement and infrastructure projects. ADB has also provided $56 million for more than 82 technical assistance studies for policy reform, institutional strengthening, environmental management, poverty reduction, and project preparation. As for the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and its plans to implement more efficient environmental and associated infrastructure provision, ADB assistance has been complemented by efforts from various other development partners, as listed below. Assistance Funded by Foreign Aid Agencies for Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region for Infrastructure and Environmental Improvement (1989 to date) Total Amount of Development Investment Loan Partner Project Name Duration ($ million) ($ million) A. Water Conservancy Tarim Basin Water Conservancy and World Bank 1998–2004 301.0 150.0 Agriculture Support B. Transport Turpan–Urumqi–Dahuang Mountain World Bank 1989–1998 15.0 Expressway World Bank Urumqi–Kuitun Expressway 1992–1997 30.0 World Bank Kuitun–Syimlake Expressway 1997–2000 413.0 150.0 World Bank Urumqi Transportation Improvement 2000–2007 281.0 100.0 Export-Import Bank of Urumqi Hetan Road 1995–998 110.0 45.0 Japan Government of the Korla Outer Ring Road 2003–2005 25.0 10.0 Republic of Korea C. Urban Environmental Improvement Yining Integrated Environment JBIC 107.0 37.0 Management Saudi Arabian Development Aksu Integrated Environment Management 2005–2008 105.0 22.0 Bank XUAR Integrated Environment Government Management (Hami, Turpan, Kuitun, 206.0 150.0 of Japan Wusu, Altay, and Atushi) Altay City Integrated Urban Environmental JBIC 2009–present 20.0 Improvement D. -

Staking Claims to China's Borderland: Oil, Ores and State- Building In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Staking Claims to China’s Borderland: Oil, Ores and State- building in Xinjiang Province, 1893-1964 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Judd Creighton Kinzley Committee in charge: Professor Joseph Esherick, Co-chair Professor Paul Pickowicz, Co-chair Professor Barry Naughton Professor Jeremy Prestholdt Professor Sarah Schneewind 2012 Copyright Judd Creighton Kinzley, 2012 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Judd Creighton Kinzley is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-chair Co- chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgments.............................................................................................................. vi Vita ..................................................................................................................................... ix Abstract ................................................................................................................................x Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1