China's Campaign to Open the West: Xinjiang and the Center by Robert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Analysis of the Genetic Diversity of Chinese Hami Melon and Its Relationship to the Melon Germplasm from Central and South Asia

J. Japan. Soc. Hort. Sci. 80 (1): 52–65. 2011. Available online at www.jstage.jst.go.jp/browse/jjshs1 JSHS © 2011 Molecular Analysis of the Genetic Diversity of Chinese Hami Melon and Its Relationship to the Melon Germplasm from Central and South Asia Yasheng Aierken1,2, Yukari Akashi1, Phan Thi Phuong Nhi1, Yikeremu Halidan1, Katsunori Tanaka3, Bo Long4, Hidetaka Nishida1, Chunlin Long4, Min Zhu Wu2 and Kenji Kato1* 1Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Okayama University, Okayama 700-8530, Japan 2Hami Melon Research Center, Xinjiang Academy of Agricultural Science, Urumuqi 830000, China 3Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto 603-8047, Japan 4Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS, Heilongtan, Kunming, Yunnan 650204, China Chinese Hami melon consists of the varieties cassaba, chandalak, ameri, and zard. To show their genetic diversity, 120 melon accessions, including 24 accessions of Hami melon, were analyzed using molecular markers of nuclear and cytoplasmic genomes. All Hami melon accessions were classified as the large-seed type with seed length longer than 9 mm, like US and Spanish Inodorus melon. Conomon accessions grown in east China were all the small- seed type. Both large- and small-seed types were in landraces from Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia. Analysis of an SNP in the PS-ID region (Rpl16-Rpl14) and size polymorphism of ccSSR7 showed that the melon accessions consisted of three chloroplast genome types, that is, maternal lineages. Hami melon accessions were T/338 bp type, which differed from Spanish melon and US Honey Dew (T/333 bp type), indicating a different maternal lineage within group Inodorus. -

Sacred Right Defiled: China’S Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom

Sacred Right Defiled: China’s Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom A Report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project Table of Contents Executive Summary...........................................................................................................2 Methodology.......................................................................................................................5 Background ........................................................................................................................6 Features of Uyghur Islam ........................................................................................6 Religious History.....................................................................................................7 History of Religious Persecution under the CCP since 1949 ..................................9 Religious Administration and Regulations....................................................................13 Religious Administration in the People’s Republic of China................................13 National and Regional Regulations to 2005..........................................................14 National Regulations since 2005 ...........................................................................16 Regional Regulations since 2005 ..........................................................................19 Crackdown on “Three Evil Forces”—Terrorism, Separatism and Religious Extremism..............................................................................................................23 -

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Schluessel, Eric T. 2016. The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493602 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 A dissertation presented by Eric Tanner Schluessel to The Committee on History and East Asian Languages in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History and East Asian Languages Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April, 2016 © 2016 – Eric Schluessel All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Mark C. Elliott Eric Tanner Schluessel The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 Abstract This dissertation concerns the ways in which a Chinese civilizing project intervened powerfully in cultural and social change in the Muslim-majority region of Xinjiang from the 1870s through the 1930s. I demonstrate that the efforts of officials following an ideology of domination and transformation rooted in the Chinese Classics changed the ways that people associated with each other and defined themselves and how Muslims understood their place in history and in global space. -

Program 1-D Eclipse-City Along China's Ancient Silk Road From

Program 1-D: Page 1 of 18 Eclipse-City along China’s Silk Road in the Xinjiang Province Program 1-D Eclipse-City along China’s Ancient Silk Road From Kashgar to Hami Eclipse-City is happy to announce its extended China eclipse-program. Our extended 2008 eclipse program for China will take you primarily to China’s Northwestern Uyghur Autonomous Province of Xinjiang. Xinjiang is the largest political subdivision of China - it accounts for more than one sixth of China's total territory, a quarter of its boundary length, but only 1.5% of its total population. It is divided into two basins by the Tianshan Mountain range. Dzungarian Basin is in the north, and Tarim Basin is in the south. Xinjiang's lowest point is located in the Turfan Depression, 155 meters below sea level (second lowest in the world). Its highest peak, K2, the second highest mountain in the world, is 8,611 meters above sea level, at the border with Pakistan. This tour, based around our core program (1A), emphasizes even more the historical richness of the Silk Road in the Xinjiang province. We will travel some 2,000 km by comfortable tourist coach busses along China’s Silk Road and experience unforgettable highlights, such as the view of crystal clear high altitude lakes surrounded by snow-caped mountains, drive along the world’s second lowest point in Turpan Basin, visit ancient caves with Buddhist paintings, shop in multi-ethnic bazaars, witness stunning sand dunes, watch and/or ride the famous Barkol horse or camels and of course, enjoy more than 2 minutes of totality in our specially built camp in the Gobi Desert. -

China COI Compilation-March 2014

China COI Compilation March 2014 ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation China COI Compilation March 2014 This COI compilation does not cover the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau, nor does it cover Taiwan. The decision to exclude Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan was made on the basis of practical considerations; no inferences should be drawn from this decision regarding the status of Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan. This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared on the basis of publicly available information, studies and commentaries within a specified time frame. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. -

The Natural Resource Curse in Xinjiang

Yin Weiwen_51128231 The Natural Resource Curse in Xinjiang Abstract Natural resource abundance may have political and economic consequences. Some argue that natural resource abundance can have a negative effect on democratic transition and the consolidation of democracy, the so-called “natural resource curse” in political aspect. But the mechanism through which natural resource stock leads to a less democratic regime with more authoritarian features is not yet fully clarified. In this paper I will use a case study about Xinjiang to test my theory. That is, distributional inequality between Han Chinese and the ethnic minorities over the resource revenue results in more resistance from the Uyghurs, thus the government responds with stricter social control. This paper is aimed at offering both a theoretical creation and an explanation for the current instability in Xinjiang. Key Words Natural Resource Curse, Xinjiang, Uyghurs, Political Economy 1 Yin Weiwen_51128231 Chapter I: Introduction The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region has never been such a hot topic among scholars and politicians as it is now. Though the Uyghur separatists have been asking for independence ever since the Chinese Communists took the place in the late 1940s, and even earlier, they could never gain so much sympathy and support from the western world as the Tibetans have been enjoying. Xinjiang remained to be a relatively marginal topic for years, while Tibetans studies continued to thrive in universities and colleges in the U.S. and Europe. But things have changed after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the independence of Central Asian countries, and the bloody riots that caused hundreds of deaths on July 5, 2009 reminds us that Xinjiang should not be neglected anymore. -

DC: PRC: Xinjiang Altay Urban Infrastructure and Environment

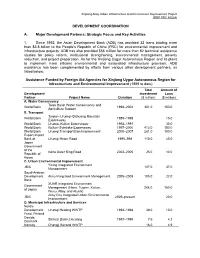

Xinjiang Altay Urban Infrastructure and Environment Improvement Project (RRP PRC 43024) DEVELOPMENT COORDINATION A. Major Development Partners: Strategic Focus and Key Activities 1. Since 1992, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has provided 32 loans totaling more than $3.8 billion to the People's Republic of China (PRC) for environmental improvement and infrastructure projects. ADB has also provided $56 million for more than 82 technical assistance studies for policy reform, institutional strengthening, environmental management, poverty reduction, and project preparation. As for the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and its plans to implement more efficient environmental and associated infrastructure provision, ADB assistance has been complemented by efforts from various other development partners, as listed below. Assistance Funded by Foreign Aid Agencies for Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region for Infrastructure and Environmental Improvement (1989 to date) Total Amount of Development Investment Loan Partner Project Name Duration ($ million) ($ million) A. Water Conservancy Tarim Basin Water Conservancy and World Bank 1998–2004 301.0 150.0 Agriculture Support B. Transport Turpan–Urumqi–Dahuang Mountain World Bank 1989–1998 15.0 Expressway World Bank Urumqi–Kuitun Expressway 1992–1997 30.0 World Bank Kuitun–Syimlake Expressway 1997–2000 413.0 150.0 World Bank Urumqi Transportation Improvement 2000–2007 281.0 100.0 Export-Import Bank of Urumqi Hetan Road 1995–998 110.0 45.0 Japan Government of the Korla Outer Ring Road 2003–2005 25.0 10.0 Republic of Korea C. Urban Environmental Improvement Yining Integrated Environment JBIC 107.0 37.0 Management Saudi Arabian Development Aksu Integrated Environment Management 2005–2008 105.0 22.0 Bank XUAR Integrated Environment Government Management (Hami, Turpan, Kuitun, 206.0 150.0 of Japan Wusu, Altay, and Atushi) Altay City Integrated Urban Environmental JBIC 2009–present 20.0 Improvement D. -

Staking Claims to China's Borderland: Oil, Ores and State- Building In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Staking Claims to China’s Borderland: Oil, Ores and State- building in Xinjiang Province, 1893-1964 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Judd Creighton Kinzley Committee in charge: Professor Joseph Esherick, Co-chair Professor Paul Pickowicz, Co-chair Professor Barry Naughton Professor Jeremy Prestholdt Professor Sarah Schneewind 2012 Copyright Judd Creighton Kinzley, 2012 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Judd Creighton Kinzley is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-chair Co- chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgments.............................................................................................................. vi Vita ..................................................................................................................................... ix Abstract ................................................................................................................................x Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1 -

IFC's FPIC and the Cultural Genocide of Uyghurs

IFC’s FPIC and the Cultural Genocide of Uyghurs A failure to apply PS7 in Xinjiang links IFC to gross human rights violations KENDYL SALCITO March 2021 IFC’s 2012 Performance Standards purport to safeguard the indigenous right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent for impacts on their lands, livelihoods and culture associated with IFC investments. Performance Standard 7 should assure that development projects on indigenous lands directly benefit and are accepted by indigenous peoples. Yet IFC has never implemented its FPIC standard in Xinjiang, despite having investments in agriculture, energy and surveillance technology in the region. The failure to adequately implement PS7 has made IFC complicit in the ethnic cleansing underway in the region. This report outlines these findings and proposes mitigation measures. 0 Executive Summary The World Bank’s private lending arm, the financing is contributing to the Uyghur cul- • The UK government has modified its International Finance Corporation (IFC), tural genocide in Xinjiang. modern slavery fines to directly penal- has committed to upholding the rights of ize companies credibly linked Xinjiang NomoGaia alerted the IFC to these con- indigenous peoples since at least 2012, abuses;ii cerns in November 2020 and engaged with with the launch of its updated Perfor- • the bank to seek evidence demonstrating The Australian and Japanese govern- mance Standards. Implementation of this that these risks are managed. Two Xinjiang ments have proposed bills to sanction commitment has come under scrutiny in products from Xinjiang;iii investments have been divested in that the past. Today, evidence suggests that period. Some of IFC’s inquiries into client • Auditors from French, UK, German and failure to adequately safeguard indigenous operations in the region have documented US firms refuse to conduct audits in the peoples is contributing to an ongoing cul- a degree of risk mitigation. -

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020 Contents Heilongjiang ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Jilin ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Liaoning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region ........................................................................................................... 7 Beijing......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Hebei ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 Henan .......................................................................................................................................................... 13 Shandong .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Shanxi ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Shaanxi ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Sedimentary Record of Mesozoic Deformation and Inception of the Turpan-Hami Basin, Northwest China

Geological Society of America Memoir 194 2001 Sedimentary record of Mesozoic deformation and inception of the Turpan-Hami basin, northwest China Todd J. Greene* Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California, 94305-2115, USA Alan R. Carroll* Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wisconsin, 1215 West Dayton Street, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA Marc S. Hendrix* Department of Geology, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA Stephan A. Graham* Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-2115, USA Marwan A. Wartes* Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wisconsin, 1215 West Dayton Street, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA Oscar A. Abbink* Laboratory of Palaeobotany and Palynology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands ABSTRACT The Turpan-Hami basin is a major physiographic and geologic feature of north- west China, yet considerable uncertainty exists as to the timing of its inception, its late Paleozoic and Mesozoic tectonic history, and the relationship of its petroleum systems to those of the nearby Junggar basin. To address these issues, we examined the late Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary record in the Turpan-Hami basin through a series of outcrop and subsurface studies. Mesozoic sedimentary facies, regional un- conformities, sediment dispersal patterns, and sediment compositions within the Turpan-Hami and southern Junggar basins suggest that these basins were initially separated between Early Triassic and Early Jurassic time. Prior to separation, Upper Permian profundal lacustrine and fan-delta facies and Triassic coarse-grained braided-fluvial–alluvial facies were deposited across a contigu- ous Junggar-Turpan-Hami basin. Permian through Triassic facies were derived mainly from the Tian Shan to the south, as indicated by northward-directed paleocurrent di- rections. -

Research on the Transformation and Upgrading of Xinjiang Jujube Industry in the Context of “Silk Road Economic Belt”

E3S Web of Conferences 235, 02027 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123502027 NETID 2020 Research on the Transformation and Upgrading of Xinjiang Jujube Industry in the Context of “Silk Road Economic Belt” Bai Xiao1,a , Kong Na2,b , Zhang Rong3,c 1 Postdoctoral Innovation Practice Base, Xinjiang Vocational and Technical College of Communications, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China 2 Science and Technology Project Service Center, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China 3 Faculty of Transportation and Management, Xinjiang Vocational and Technical College of Communications, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China Abstract. Jujube planting in Xinjiang, China began in 1985, and then entered the rapid development stage of planting. By 2012, Xinjiang became the main jujube producing area in China. Due to its geographical advantage, jujube in Xinjiang, China is of high quality and has become another agricultural product with Chinese Xinjiang characteristics. However, jujube production in China has declined since 2013.Although China’s Xinjiang planting area is still expanding, the price of jujube has been affected by a significant decline, and has been maintained at a low level in recent years. Farmers' income has decreased, and the bottleneck of jujube industry development has become prominent. Therefore, industrial transformation and upgrading is imminent. This paper combines in-depth analysis of jujube related data from 2007 to 2016, finds out the existing problems, and proposes the path for the transformation and upgrading of the jujube industry