Ellen Stewart La Mama of Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vernon Haley Appointed New Dean of Students

B4NDDR4SBCK Vol. XXXI No. 7 York College of the City University of New York Jamaica, Queens April 29,1988 JacksonNo Show Causes Disappointment And Conflict By Lisa Toppin Feature Editor Jesse Jackson, Democratic presi- dential candidate, was scheduled to speak in York College's central mall on Friday, April 15. Instead of an inspiring speech, the students and faculty gathered in the mall received the disappointing news that the Reverend Jackson would not be coming. The day before, there were rumors that Jackson might cancel his visit. The mall was decorated with Jackson banners, posters and red, white, and blue balloons. There was an electricity in the air. All students seemed to talk Brenda White, Jackson's Queens Manager. about was Jackson's imminent visit. Jackson at York," said Katherine Lake, "He is the hope for minorities," said a student leader. "We put a lot of money Zak Hasan, president of the Business and effort into this event to make it Club. "He is the hope for our future happen." and our kid's future." Lake and other event organizers felt At about 11:30 a.m., when it was that the administration would not allow apparent that Jackson was not going a black political figure to speak at to arrive, Brenda White, Queens YSG President Donald Vernon vents anger after cancellation announced. York. They said that Bassin is one Manager in the Jesse Jackson campaign, of the "Mayor's boys" and he wouldn't formally announced that the visit was There was an overwhelming sense one dejected student. "I've been looking "go against" Mayor Koch and support cancelled. -

The Caffe Cino

DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino LOCATION Borough of Manhattan 31 Cornelia Street LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE No. 31 Cornelia Street in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan is culturally significant for its association with the Caffe Cino, which occupied the building’s ground floor commercial space from 1958 to 1968. During those ten years, the coffee shop served as an experimental theater venue, becoming the birthplace of Off-Off-Broadway and New York City’s first gay theater. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 Former location of the Caffe Cino, 31 Cornelia Street 2019 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Sarah Carroll, Chair Mark Silberman, Counsel Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Diana Chapin Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Wellington Chen Michael Devonshire REPORT BY Michael Goldblum MaryNell Nolan-Wheatley, Research Department John Gustafsson Anne Holford-Smith Jeanne Lutfy EDITED BY Adi Shamir-Baron Kate Lemos McHale and Margaret Herman PHOTOGRAPHS BY LPC Staff Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 3 of 24 The Caffe Cino the National Parks Conservation Association, Village 31 Cornelia Street, Manhattan Preservation, Save Chelsea, and the Bowery Alliance of Neighbors, and 19 individuals. No one spoke in opposition to the proposed designation. The Commission also received 124 written submissions in favor of the proposed designation, including from Bronx Borough President Reuben Diaz, New York Designation List 513 City Council Member Adrienne Adams, the LP-2635 Preservation League of New York State, and 121 individuals. -

Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation East Village Oral History Project

GREENWICH VILLAGE SOCIETY FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION EAST VILLAGE ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Oral History Interview VIRLANA TKACZ By Rosamund Johnston New York, NY March 17, 2014 Oral History Interview with Virlana Tkacz, March 17, 2014 Narrator Virlana Tkacz Birthdate 6/23/1952 Birthplace Newark, NJ Narrator Age 61 Interviewer Rosamund Johnston Place of Interview Virlana Tkacz’s Apartment on East 11th Street Date of Interview 3/17/2014 Duration of Interview 1h 15mins Number of Sessions 1 Waiver Signed/copy given Yes Photo (y/n) n/a Format Recorded .Wav, 48 Khz, 16 Bit Archival File Names MZ000007-11 Virlana Tkacz 1.mp3, Virlana Tkacz 2.mp3, Virlana Tkacz 3,mp3, Virlana Tkacz 4.mp3, MP3 File Name Virlana Tkacz 5.mp3 Order in Oral Histories RJ 2 Tkacz-ii Virlana Tkacz in rehearsals in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, 2010. Photograph by V. Voronin. Tkacz-iii Quotes from Oral History Interview with Virlana Tkacz “In the Sixties, there was a neighborhood with two worlds that walked past each other, that didn’t see each other—totally didn’t see each other. I remember coming to visit when I was young. My grandfather’s sister lived on St. Mark’s. And we were all dressed up, Easter clothes, all this kind of stuff, patent leather shoes. My mother was herding all of us in. And the neighbors across the hall opened the door, and there’s a bunch of kids living there, obviously, like hippies. I had never seen hippies before. They had a mattress on the floor, and there was like nothing else in the house. -

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 17, 2009, Designation List 423 LP-2328

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 17, 2009, Designation List 423 LP-2328 ASCHENBROEDEL VEREIN (later GESANGVEREIN SCHILLERBUND/ now LA MAMA EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE CLUB) BUILDING, 74 East 4th Street, Manhattan Built 1873, August H. Blankenstein, architect; facade altered 1892, [Frederick William] Kurtzer & [Richard O.L.] Rohl, architects Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 459, Lot 23 On March 24, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Aschenbroedel Verein (later Gesangverein Schillerbund/ now La Mama Experimental Theatre Club) Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 11). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Four people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the Municipal Art Society of New York, Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, and Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission received a communication in support of designation from the Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in America. Summary The four-story, red brick-clad Aschenbroedel Verein Building, in today’s East Village neighborhood of Manhattan, was constructed in 1873 to the design of German-born architect August H. Blankenstein for this German-American professional orchestral musicians’ social and benevolent association. Founded informally in 1860, it had grown large enough by 1866 for the society to purchase this site and eventually construct the purpose-built structure. The Aschenbroedel Verein became one of the leading German organizations in Kleindeutschland on the Lower East Side. It counted as members many of the most important musicians in the city, at a time when German-Americans dominated the orchestral scene. -

3. New York City's Theater

Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit Stage New York City Verfasserin Katja Moritz Angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil) Wien, im Oktober 2008 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuerin/Betreuer: Ao. Univ.- Prof. Dr. Brigitte Marschall INDEX__________________________________________ 1. PREFACE AND INTRODUCTION …………………………………. Seite 4 2. INTRO: BIG CITY LIFE ……………………………………………... Seite 6 2.1. Introduction New York …………………………………………. Seite 8 3. NEW YORK CITY‘S THEATER ……………………………………. Seite 12 3.1.1. Broadway, Off And Off-Off Broadway: Differences ...………….. Seite 13 4. BROADWAY …………………………………………………………... Seite 16 4.1. New York City’s Broadway – What Is It About? ……………….. Seite 18 4.2. Broadway History: Changes …………………………………….. Seite 21 4.2.1. Early Attraction ……………………………………………………... Seite 21 4.2.2. Broadway 1900 – 1950 ……………………………………………… Seite 24 4.2.3. Broadway 1950 – 2008 ……………………………………………… Seite 26 4.3. Commercial Production: Broadway ……………………………... Seite 27 4.3.1. Broadway Producer: Money Makes The (Broadway) World Go Round ………………….. Seite 29 4.3.2. Critics: Thumbs Up? ………………………………………………… Seite 32 4.3.3. Musical ……………………………………………………………… Seite 33 4.4. Competition Calls For Promotion ……………………………….. Seite 35 4.4.1. Federal Theatre Project 1935 – 1939 ………………………………... Seite 36 4.4.2. Theatre Development Fund TDF ……………………………………. Seite 37 4.4.3. I Love NY …………………………………………………………… Seite 38 4.5. Reflection ………………………………………………………... Seite 39 5. OFF AND OFF-OFF BROADWAY DEVELOPMENT ……………. Seite 41 5.1. Showplace Greenwich Village And East Village ……………….. Seite 41 5.2. Showplace Williamsburg, Brooklyn …………………………….. Seite 45 1 6. OFF BROADWAY AND OFF-OFF BROADWAY – WHAT IS IT ABOUT? ………………………………………………... Seite 47 6.1. First Steps Into Off Broadway …………………………………… Seite 48 6.2. The Real Off Broadway – The 1950s ……………………………. -

THE REST I MAKE up a Film by Michelle Memran

Documentary Feature US, 2018, 79 minutes, Color, English www.wmm.com THE REST I MAKE UP A film by Michelle Memran The visionary Cuban-American dramatist and educator Maria Irene Fornes spent her career constructing astonishing worlds onstage and teaching countless students how to connect with their imaginations. When she gradually stops writing due to dementia, an unexpected friendship with filmmaker Michelle Memran reignites her spontaneous creative spirit and triggers a decade-long collaboration that picks up where the pen left off. The duo travels from New York to Havana, Miami to Seattle, exploring the playwright's remembered past and their shared present. Theater luminaries such as Edward Albee, Ellen Stewart, Lanford Wilson, and others weigh in on Fornes’s important contributions. What began as an accidental collaboration becomes a story of love, creativity, and connection that persists even in the face of forgetting. WINNER! Audience Award, Best Documentary: Frameline Film Festival 2018 WINNER! Jury Award for Best Documentary, Reeling: Chicago LGBTQ+ Int’l Film Festival WINNER! AARP Silver Image Award, Reeling: Chicago LGBTQ+ Int’l Film Festival WINNER! Jury Award for Best Documentary, OUTshine Film Festival Special Mention, Queer Porto 4 - International Queer Film Festival One of the “Best Movies of 2018” Richard Brody, THE NEW YORKER "A lyrical and lovingly made documentary." THE NEW YORK TIMES "Intimate and exhilarating...Fornes exerts a hypnotic force of stardom, while her offhanded yet urgent remarks resound with life-tested literary authority. " THE NEW YORKER "A story of spontaneity, creativity, genius and madness. It showcases the life, inspiration and virtuosity of Fornes." MIAMI HERALD "A tender exploration of Fornes’ life and the meaning of memory." CONDÉ NAST’S THEM "Fabulous. -

The TRINITY TRI

The TRINITY TRI Vol.LXXXII, Issue 17 TRINITY COLLEGE, HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT ! February 14, 1984, New Coordinator Plans For Future by Ross Lemmon Zurles a very tentative schedule of Senior Staff Writer programs was proposed includ- ing, for the near future, Women's Judith Zurles, who has an ex- Health, assault prevention and self tensive background in counselling defense, and for around exam and who most recently created a time, programs on study skills, Women's Center and Maohecad time management, stress manage- Community College where she was ment and relaxation techniques. Director of the Lifelong Learning Zurles also plans to continue the Program,, has recently taken over lunchtime series which has been as Coordinator and Counselor at very successful for the Women's the Trinity Women's Center, lo- Center in the past. cated on the third floor of the . For the time being, in addition Mather Campus Center, one flight to her counselling responsibilities, up from the Washington Room. three days a week which she feels With only three day's experi- should. be extended to meet the ence at Trinity, Zurles was under- needs of the student body, Zurles standably not able to be very is occupying her time in getting a specific yet as to what responsibil- feel for the relationship between ities her position entails, but she the Women's Center and the rest was able to make some general of the College community, "tal- comments as to what she would king with a lot of people and find- like to see the Women's Center do ing out what they feel is lacking Photo by Penny Perkins in the future. -

Coffeehouse Chronicles #154 Taylor Mac

Coffeehouse Chronicles #154 Taylor mac Michal Gamily - Series Director Arthur Adair - Educational Outreach Ellen Stewart Theatre 66 East 4th Street, NYC, 10003 June 8, 2019 Coffeehouse Chronicles Honors the career and achievements of American actor, playwright, performance artist, director, producer and MacArthur Fellow recipient Taylor Mac with panelists, live performances and archival materials. Moderated by Gabriel Berry With Morgan Jenness, Melanie Joseph, Niegel Smith, Barbara Maier Gusten, Timothy White Eagle, Linda Brumbach. Appearing on Video: Machine Dazzle Live Music by Matt Ray (Piano) Gary Wang (Bass) Viva DeConcini (Guitar) Bernice “Boom Boom” Brooks (Drums) Greg Glassman (Trumpet) COFFEEHOUSE CHRONICLES STAFF Director/Curator: Michal Gamily Educational Outreach: Arthur Adair Stage Manager: Jialin (Liz) He Resident Audio Visual Designer: Hao Bai Video Production Manager / Photographer: Theo Cote Digital Media: Ryan Leach Director of Archive: Ozzie Rodriguez Archive Project Manager: Sophie Archive/Resident Artistic Associate: Shigeko Suga Prologue Taylor reads a monologue (Lilies Revenge or Prosperous Fools) Live performance: Turn, Turn,Turn (Taylor and the band) Gabriel Berry introduces Whitey Part 1: Playwriting Morgan Jenness leads the exploration of Taylor’s work as a playwright Taylor reads excerpts from his new play Live performance: Taylor plays the uke Part 2: The visual world Machine Dazzle ’s interview Slideshow presentation of show images of the last 25 years Whitey and Niegel Smith about Taylor’s aesthetic Live performance: Ghost Riders (Taylor and the band) Linda Brumbach about producing the A 24- Decade History of Popular Music Barbara Maier Gusten about Vocal lessons and performing at the A 24- Decade History of Popular Music Part 3: Audience interaction and Q&A Melanie Joseph about audience interaction in Taylor’s world Melanie leads a Q&A Live performance: A scene from A Walk Across America for Mother Earth (La MaMa 2011) Taylor leads the audience in the sing-a-long. -

<I>Ellen Stewart Presents: Fifty Years of La Mama Experimental Theatre</I>

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadt.commons.gc.cuny.edu Ellen Stewart Presents: Fifty Years of La MaMa Experimental Theatre Ellen Stewart Presents: Fifty Years of La MaMa Experimental Theatre. Cindy Rosenthal. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017; Pp. 198. Ellen Stewart Presents: Fifty Years of La MaMa Experimental Theatre is the first book-length study to chronicle Ellen Stewart’s exceptional contributions to twentieth and twenty-first century theatre. Written by expert in U.S. theatre Cindy Rosenthal, the book is ambitious in scope and stays true to the idiosyncratic tenets of avant-garde theatre that made Ellen Stewart famous. Rosenthal began research for the project in 2006 when TDR commissioned her to write a comprehensive article about La MaMa. Until this point, Ellen Stewart had been fiercely guarded about her privacy and determined that no book would be written about her or La MaMa. However, Rosenthal’s article pleased Stewart, so she agreed to a manuscript with the caveat that Rosenthal approach the book through the lens of La MaMa’s vast poster collection and through the words of the artists who had passed through La MaMa’s doors since its inception in 1961. The result is a historical narrative of colorful anecdotes, archival photographs, and rare posters that examine La MaMa’s longevity as the foremost Off-Off-Broadway venue. Ellen Stewart Presents is primarily an archival and ethnographic study that is organized into five chronological chapters beginning with the 1960s and ending in 2011, shortly after Stewart’s death at the age of ninety-one. -

Alaska CARES a Clinic Providing Sexual and Physical Abuse Evaluations for Children up to Age 18

FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Welcome, Tonight we celebrate the world premiere of Vera Starbard’s beautiful play, Our Voices Will Be Heard. What you will see in Vera’s debut work is a play about a terribly difficult subject: sexual abuse. It’s also about a mother’s and daughter’s strength in the face of limited options. It is a “ It is a play that took great courage to write. One of my earliest theatre memories at Perseverance was a production play that of Paula Vogel’s play about AIDS called The Baltimore Waltz. The AIDS epidemic was at its height, and Paula’s play was the first artful work took great on this tragic and important subject that I had seen. I thought of Paula when meeting Vera Starbard a few years ago because Vera’s story about a girl coming of age while dealing with a sexually abusive uncle courage to brought up Paula’s 1998 Pulitzer Prize-winning play, How I Learned to Drive. write. Over time, I’ve become aware of an interesting resonance with the ” younger Paula Vogel’s earlier work. Both are very theatrical, deeply personal, and written to build understanding of an ongoing tragedy. Stigma, victim blaming, and challenges in empathizing with the human beings caught up in abusive situations are common threads in both writers’ work. The plays are starkly different, but on a deeper level there is a connection in their approaches: both writers are writing what they know. Both writers draw on personal experience and create a theatricalized version of lived reality in order to examine it with their audience. -

Caffe Cino Multiple Property Listing: No Other Names/Site Number 2

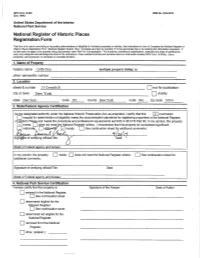

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Caffe Cino multiple property listing: no other names/site number 2. Location street & number 31 Cornelia St not for publication city or town New York vicinity state New York code NY county New York code 061 zip code 10014 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this x nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide x locally. -

Author: Publisher: Description: 100 (Monologues)

Title: 100 (monologues) Author: Bogosian, Eric Publisher: Theatre Communications Group 2014 Description: Monologues – American “100 (monologues)” collects all of Eric Bogosian’s monologues, originally performed as part of his six Off-Broadway solo shows, including “Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll,” “Pounding Nails in the Floor with My Forehead,” “Wake Up and Smell the Coffee,” “Drinking in America,” “funhouse,” “Men Inside,” and selections from his play “Talk Radio.” For these shows, first performed between 1980 and 2000, Bogosian was awarded three Obie Award and a Drama Desk Award—earning him living-icon status in the downtown theater scene. Contains monologues from the following plays by Eric Bogosian: Men Inside ; Voices of America ; Men in Dark Times ; Advocate ; Funhouse ; Drinking in America ; Talk Radio ; Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll ; Notes From Underground ; Pounding Nails in the Floor With My Forehead ; 31 Ejaculations ; Wake Up and Smell the Coffee ; This is Now! ; Orphans Title: 100 Great Monologues from the Neo-Classical Theater Author: Publisher: Smith and Kraus 1994 Description: Monologues – auditions - classics Contains monologues from the following plays and playwrights: Women’s monologues: All for Love – John Dryden ; Andromache – Jean Racine ; The Beaux’ Stratagem – George Farquhar ; The Burial of Danish Comedy – Ludvig Holberg ; Cato – Joseph Addison ; The Careless Husband – Colley Cibber ; Careless Vows – Marivaux ; Cinna – Pierre Cornielle ; The Clandestine Marriage – George Coleman and David Garrick ; The Contrast – (2) Royall