Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opening the Island

Mayumi Itoh. Globalization of Japan : Japanese Sakoku mentality and U. S. efforts to open Japan. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998. 224 pp. $45.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-312-17708-9. Reviewed by Sandra Katzman Published on H-US-Japan (February, 1999) Japan is ten years into its third kaikoku, or reader in the Japanese mentality through these open door policy, in modern history. phrases without requiring Japanese or Chinese This book is well-organized into two parts: scripts. Some of the most important words are "The Japanese Sakoku Mentality" and "Japan's Kokusaika: internationalization Gaijin: out‐ Sakoku Policy: Case Studies." Although its subject sider, foreigner Kaikoku: open-door policy includes breaking news, such as the rice tariffs, Saikoku: secluded nation Gaiatsu: external pres‐ the book has a feeling of completion. The author, sure Mayumi Itoh, has successfully set the subject in Part I has fve chapters: Historical Back‐ history, looking backward and looking forward. ground, the Sakoku Mentality and Japanese Per‐ Itoh is Associate Professor of Political Science at ceptions of Kokusaika, Japanese Perceptions of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. the United States, Japanese Perceptions of Asia, Itoh argues that although globalization is a and Japanese Perceptions of ASEAN and Japan's national policy of Japan, mental habits preclude Economic Diplomacy. its success. She sets the globalization as the third Part II has fve chapters: Japan's Immigration in a series of outward expansions, each one pre‐ and Foreign Labor Policies, Okinawa and the cipitated by the United States. The style of writing Sakoku Mentality, Kome Kaikoku: Japan's Rice is scholarly and easy to understand. -

2 Patterns of Immigration in Germany and Japan

Thesis ETHNIC NATION-STATES AT THE CROSSROADS Institutions, Political Coalitions, and Immigration Policies in Germany and Japan Submitted by Jan Patrick Seidel Graduate School of Public Policy In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Public Policy The University of Tokyo Tokyo, Japan Summer 2015 Advisor: Kentarō Maeda Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor Kentarō Maeda for the direction and advice in writing my thesis. I would also like to thank Chisako Kaga, my family and friends in Germany and Japan for the unconditional emotional support. Finally, I would like to thank the University of Tokyo for the financial assistance that made my stay in Japan possible. 誠にありがとうございました! Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... II ABBREVIATION INDEX .......................................................................................... 1 ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 5 1. THEORIES OF IMMIGRATION POLICY-MAKING AND THE CASES OF GERMANY AND JAPAN .................................................................................................................12 1.1 Theoretical and methodological considerations .....................................12 1.1.1 Three theory streams of immigration and integration policy-making ..12 1.1.2 -

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and Japan’S International Family Law Including Nationality Law

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and Japan’s International Family Law including Nationality Law Yasuhiro Okuda * I. Introduction II. Registration of Birth and Right to Nationality 1. Overview 2. Registration of Birth 3. Elimination of Statelessness 4. Nationality of Child out of Wedlock III. Right to Preserve Nationality 1. Retention of Nationality 2. Selection of Nationality 3. Acquisition or Selection of Foreign Nationality IV. International Family Matters 1. Intercountry Adoption 2. Recovery Abroad of Maintenance 3. International Child Abduction V. Conclusion I. INTRODUCTION The rights of children seem at first glance to be much better protected in Japan than in most other countries. Most Japanese children are well fed, clothed, educated, and safe from life threatening harm. Thus, the Japanese government found neither new legis- lation, reform of existing laws, nor accession to other conventions necessary when in 1994 it ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (hereafter the “Child Convention”).1 However, the Child Convention regulates not only the basic human needs mentioned above, but also a variety of human rights such as the right to nationality and the right to registration of one’s birth. It further deals with various family matters with foreign elements such as inter-country adoption, recovery abroad of maintenance, and international child abduction. * This article is reprinted from Hokudai Hôgaku Ronshû, Vol. 54, No. 1, 456 and based in part on a report regarding the Child Convention that the author prepared on behalf of the Japan Federation of Bar Associations. The author thanks Professor Kent Anderson (The Australian National University) for his comments, advice, and revising the English text. -

Migration and Transnationalism of Japanese Americans in the Pacific, 1930-1955

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ BEYOND TWO HOMELANDS: MIGRATION AND TRANSNATIONALISM OF JAPANESE AMERICANS IN THE PACIFIC, 1930-1955 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Michael Jin March 2013 The Dissertation of Michael Jin is approved: ________________________________ Professor Alice Yang, Chair ________________________________ Professor Dana Frank ________________________________ Professor Alan Christy ______________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Michael Jin 2013 Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: 19 The Japanese American Transnational Generation in the Japanese Empire before the Pacific War Chapter 2: 71 Beyond Two Homelands: Kibei and the Meaning of Dualism before World War II Chapter 3: 111 From “The Japanese Problem” to “The Kibei Problem”: Rethinking the Japanese American Internment during World War II Chapter 4: 165 Hotel Tule Lake: The Segregation Center and Kibei Transnationalism Chapter 5: 211 The War and Its Aftermath: Japanese Americans in the Pacific Theater and the Question of Loyalty Epilogue 260 Bibliography 270 iii Abstract Beyond Two Homelands: Migration and Transnationalism of Japanese Americans in the Pacific, 1930-1955 Michael Jin This dissertation examines 50,000 American migrants of Japanese ancestry (Nisei) who traversed across national and colonial borders in the Pacific before, during, and after World War II. Among these Japanese American transnational migrants, 10,000-20,000 returned to the United States before the outbreak of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and became known as Kibei (“return to America”). Tracing the transnational movements of these second-generation U.S.-born Japanese Americans complicates the existing U.S.-centered paradigm of immigration and ethnic history. -

Non Citizens, Voice, and Identity: the Politics of Citizenship in Japan's

The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies CCIS University of California, San Diego Non citizens, Voice, and Identity: the Politics of Citizenship in Japan’s Korean Community By Erin Aeran Chung Harvard University Working Paper 80 June 2003 1 Noncitizens, Voice, and Identity: The Politics of Citizenship in Japan’s Korean Community Erin Aeran Chung Program on U.S.-Japan Relations Harvard University Weatherhead Center for International Affairs 1033 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138-5319 [email protected] Prepared for delivery at the First Annual Summer Institute on International Migration Conference, University of California, San Diego, June 20-22, 2003. The research for this paper was supported by a grant from the Japan Foundation. 2 Abstract This paper examines the relationship between citizenship policies and noncitizen political behavior, focusing on extra-electoral forms of political participation by Korean residents in Japan. I analyze the institutional factors that have mediated the construction of Korean collective identity in Japan and, in turn, the ways that Korean community activists have re-conceptualized possibilities for their exercise of citizenship as foreign residents in Japan. My empirical analysis is based on a theoretical framework that defines citizenship as an interactive process of political incorporation, performance, and participation. I posit that the various dimensions of citizenship—its legal significance, symbolic meaning, claims and responsibilities, and practice—are performed, negotiated, -

Household Registration and Japanese Citizenship 戸籍主義 戸籍と日本国籍

Volume 12 | Issue 35 | Number 1 | Article ID 4171 | Aug 29, 2014 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Jus Koseki: Household registration and Japanese citizenship 戸籍主義 戸籍と日本国籍 Karl Jakob Krogness on the development of the koseki system (and the changing household unit it shapes) and the The anthology Japan’s household registration outcaste registers of the early modern period, system and citizenship: Koseki, identification as well as early Meijihinin fraternities, and documentation, David Chapman and Karl international marriage, and ways in which the Jakob Krogness, eds. (Routledge 2014) provides koseki as an ordering tool inevitably, down to a first, extensive, and critical overview of today, creates chaos and ‘strangers’ and Japan’s koseki system. Situated from the ‘undecidables.’ seventh century Taika Reforms until today at the center of Japanese governance and society, The following revised chapter from the book the koseki opens up for comprehensive and examines the koseki register as the official deep exploration the Japanese state, family, ledger of citizens 日本国民登録簿( ) and and individual, as well as questions relating to interrogates Japanese legal citizenship: to what citizenship, nationality, and identity. The scope extent is citizenship actually based on the of potential koseki-related research is extensive Japanese Nationality Law’s principle ofjus and is relevant for many disciplines including sanguinis (the principle whereby a child’s history, sociology, law, ethnography,citizenship follows that of the parent(s), as anthropology, -

Citizenship and North Korea in the Zainichi Korean Imagination: the Art of Insook Kim 郷愁 キム・インスクの作品 における在日朝鮮人の表象

Volume 13 | Issue 5 | Number 3 | Article ID 4263 | Feb 02, 2015 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Citizenship and North Korea in the Zainichi Korean Imagination: The Art of Insook Kim 郷愁 キム・インスクの作品 における在日朝鮮人の表象 Young Min Moon thousand years, many traditional homes can still be found in the narrow alleys around Nijo Young Min Moon with an Introduction by Castle, a World Heritage Site where Shogun Sonia Ryang Tokugawa Ieyasu is believed to have stayed. The house, bearing a nameplate reading "Ko Introducing Young Min Moon's Reflection Kang-ho/Lee Mi-o," was built about 90 years on the Photographic Art of Insook Kim ago[….] Sonia Ryang "Welcome." The voice that rang out was high and gentle. This was Kang-ho's wife Ri Mi-oh, An article in the Hankyoreh a few months back 55. A doctor of respiratory medicine, she treats caught my attention. The story is about Ko patients with terminal cancer at a hospital in Kang-ho and Ri Mi-oh, a married couple of Kobe, a city in nearby Hyogo Prefecture. The Zainichi Koreans living in Kyoto. Recently Mr. date of the visit happened to be a national Ko had filed a lawsuit in Seoul City Court holiday: National Foundation Day, requesting that his South Korean nationality be commemorating the accession of Japan's first annulled. Ko had become a South Korean emperor Jimmu. Other holidays include Showa national upon his parents' acquiring that Day, which honors the birthday of the late nationality after the 1965 normalization of emperor Hirohito, and the Emperor's Birthday, diplomatic relations between Japan and the for current emperor Akihito. -

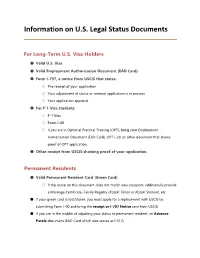

Information on U.S. Legal Status Documents

Information on U.S. Legal Status Documents For Long-Term U.S. Visa Holders ● Valid U.S. Visa ● Valid Employment Authorization Document (EAD Card) ● Form I-797, a notice from USCIS that states: ○ The receipt of your application ○ Your adjustment of status or renewal application is in process ○ Your application approval ● For F-1 Visa students: ○ F-1 Visa ○ Form I-20 ○ If you are in Optional Practical Training (OPT), bring your Employment Authorization Document (EAD Card), OPT I-20, or other document that shows proof of OPT application. ● Other receipt from USCIS showing proof of your application. Permanent Residents ● Valid Permanent Resident Card (Green Card) ○ If the name on this document does not match your passport, additionally provide a Marriage Certificate, Family Registry (Koseki Tohon or Koseki Shohon), etc. ● If your green card is lost/stolen, you must apply for a replacement with USCIS by submitting Form I-90 and bring the receipt or I-797 Notice sent from USCIS. ● If you are in the middle of adjusting your status to permanent resident, an Advance Parole document (EAD Card which also serves as I-512) Multiple Citizenship Holders ● If you were born in the U.S. ○ Birth Certificate or U.S. passport ● If you were born outside of the U.S. and obtained citizenship from a U.S. citizen parent ○ Consular Report of Birth Abroad (birth certificate issued by the U.S. Embassy or Consulate) ● If you obtained U.S. citizenship as a minor from a parent who became a naturalized U.S. citizen ○ Certificate of Citizenship ○ If you did not apply for the Certificate of Citizenship but have a U.S. -

A Case Study on the Korean Minority in Japan Onuma Yasuaki

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Cornell Law Library Cornell International Law Journal Volume 25 Article 2 Issue 3 Symposium 1992 Interplay between Human Rights Activities and Legal Standards of Human Rights: A Case Study on the Korean Minority in Japan Onuma Yasuaki Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Yasuaki, Onuma (1992) "Interplay between Human Rights Activities and Legal Standards of Human Rights: A Case Study on the Korean Minority in Japan," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 25: Iss. 3, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol25/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Onuma Yasuaki* Interplay Between Human Rights Activities and Legal Standards of Human Rights: A Case Study on the Korean Minority in Japan I. An Invisible Minority As of December 1990, 687,940 Koreans lived in Japan as aliens.' In addition, there are Japanese nationals of Korean descent (either natural- ized 2 or born to marriages between Japanese and Koreans3 ) and illegal immigrant Koreans. The total population of the ethnic Korean minority in Japan is presumably between 800,000 and 900,000. Thus, although Koreans constitute the largest ethnic minority in Japan, they comprise somewhat less than 0.8 percent of the population. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Negotiating Gender Equality in Daily Work: An Ethnography of a Public Women’s Organisation in Okinawa, Japan Yoko Narisada PhD in Social Anthropology University of Edinburgh 2010 1 Declaration I declare that this work has been composed entirely by me and is completely my own work. No part of it has been submitted for any other degree. Yoko Narisada 29 July 2010 2 Abstract This doctoral research is a contribution to the understanding of social activism and its socio-cultural formation in postcolonial Okinawa. It is based on eighteen months of fieldwork including participant observation and interviews at a public women’s organisation, Women’s Organisation Okinawa (WOO). This project centres on the lived practices of staff who attempted to produce and encourage gender equality in the public sector under neoliberal governance. -

Citizenship/Residency/Immigration/SOFA/Passports (CRISP) FAQ 1) I Am Not a US National, Can I Work for MCCS As a NAF Employee? Yes, Under Certain Conditions

Citizenship/Residency/Immigration/SOFA/Passports (CRISP) FAQ 1) I am not a US National, can I work for MCCS as a NAF employee? Yes, under certain conditions. a. IAW DODI 1400.25 V731, MCCS positions require a T1 investigation. i. Non-US Nationals CAN obtain Tier 1 (T1) suitability for federal employment if they are able to fully complete the SF85 investigation form, the DCSA is able to perform a full investigation, and the DODCAF is able to make a favorable adjudication. For more details about completing an SF85, please contact Personnel Security. ii. MCCS NAF employees are covered under HSPD-12 and must obtain and maintain a common access card (CAC) as a condition of employment. IAW DOD 5200.46 non-US Nationals must have a favorable T1 adjudication in order to obtain a CAC. b. Some MCCS positions require a National Security clearance; also known as a Tier 3 (T3), Secret, or Tier 5 (T5), Top Secret, clearance. i. IAW DODD 5200.02, non-US Nationals are not able to obtain a clearance. c. The US-Japan Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) only allows US Nationals to be independently SOFA sponsored. i. This means that it is possible for a non-US National to fall under SOFA as a dependent, but not possible for them to be the sponsor. ii. A dependent who is a foreign national may work for MCCS as long as they remain a dependent under their sponsor’s SOFA. 2) I am a dual-national, can I work for MCCS as a NAF employee? Yes. -

China and Taiwan RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-CR 2016/10 October 2016

CITIZENSHIP COUNTRY REPORT 2016/10 REPORT ON CITIZENSHIP OCTOBER 2016 LAW: CHINA AND TAIWAN AUTHORED BY CHOO CHIN LOW © Choo Chin Low, 2016 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. EUDO Citizenship Observatory Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies in collaboration with Edinburgh University Law School Report on Citizenship Law: China and Taiwan RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-CR 2016/10 October 2016 © Choo Chin Low, 2016 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), created in 1992 and directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes, projects and data sets, in addition to a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration, the expanding membership of the European Union, developments in Europe’s neighbourhood and the wider world.