On the Centuriation of Roman Britain. by HENRY CHARLES COOTE, Esq., F.S.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Betar and Aelia Capitolina: Symbols of Jewish Suffering Dr

Betar and Aelia Capitolina: Symbols of Jewish Suffering Dr. Jill Katz Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology, Yeshiva University Of the five specific tragedies that warrant fasting on Tishah b’Av (Mishnah Taanit 4:6), two are related to the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome. The first is the capture of the city of Betar (135 CE) and the second is the plowing of Jerusalem one year later. At first glance, these calamities do not seem to be of the same scale as the destruction of the First and Second Temples. The Jews were neither forcibly removed en masse to a distant land nor was a standing Temple destroyed. Perhaps one could argue that their inclusion within the list was simply due to their still being fresh in people’s memories. Surely, the rabbis of the Mishnaic period would have encountered eyewitnesses to these events and been moved by their recollections. Yet, if this were so, then the Mishnah really need only include one reference to the rebellion. By including two, the Mishnah is teaching us something about the magnitude of this tragedy and the challenges that lay ahead for the Jewish people. Betar If not for the Bar Kokhba rebellion, it is unlikely many people would be familiar with Betar. The ancient city (Khirbet el-Yahud – “ruin of the Jews”) was a modest settlement southwest of Jerusalem in the Judean Hills. Surveys and brief excavations have demonstrated that Betar was first settled during the period of the Shoftim and became a city of moderate importance by the time of Hizkiyahu. -

CALVARY CHAPEL HONOLULU TOUR of ISRAEL Saturday, November 2 – Friday, November 15, 2019

CALVARY CHAPEL HONOLULU TOUR OF ISRAEL Saturday, November 2 – Friday, November 15, 2019 Register online at www.inspiredtravel.com/hon19 Send a check payable to: Day Tour Date Proposed Itinerary Hotels Inspired Travel 3000 W. MacArthur Blvd. #450 Santa Ana, CA 92704 Day 1 Sat 2-Nov Depart USA on your overnight flight to Tel Aviv Night on Plane Please include IT HONLU19IS on all checks and correspondence. Day 2 Sun 3-Nov Arrive in Tel Aviv, transfer to hotel Crowne Plaza, Jerusalem Estimated price of *$4798 from Honolulu, HI, per person, double occupancy includes: Round-trip Day 3 Mon 4-Nov Mount of Olives, Palm Sunday Road, Garden of Gethsemane, Crowne Plaza, Jerusalem airfare to Tel Aviv on a scheduled carrier, 11 days touring the sites listed in Israel, First Class Southern Steps, City of David (Jeremiah's Cistern, Hezekiah's hotels with breakfast and dinner daily plus one lunch, and all transfers, entrance fees, taxes and Tunnel, Pool of Siloam), Western Wall Tunnels, Yad Vashem (Holocaust Museum) tips to hotels, drivers and guides. (Land Only price of *$3113 per person, double occupancy includes: all accommodations except airfare and airport transfers) Day 4 Tue 5 - Nov Wailing Wall, Ophel Digs, Southern Steps, Jewish Quarter, Burnt Crowne Plaza, Jerusalem House, Cardo, Hezekiah's Wall, Arab Market, Jaffa Gate, Elah A deposit of $400 per person is due at registration in order to secure your spot on this Valley tour. All registrations will be processed on a space-available basis. A second deposit of 50% of Day 5 Wed 6-Nov View Bethlehem and Shepherds' Fields, remainder of the day free Crowne Plaza, Jerusalem the tour costs and a copy of your passport will be due by May 2, 2019. -

“Roman Centuriation” in Rural Venetian Territory

Research in Human Ecology Cultural Landscape: Trace Yesterday, Presence Today, Perspective Tomorrow For “Roman Centuriation” in Rural Venetian Territory Gian Umberto Caravello Istituto di Igiene, Laboratorio di Ecologia Umana e Salute del Territorio Università degli Studi di Padova via Loredan 18 – 35131 Padova, Italy Piero Michieletto Dipartimento di Costruzione dell’Architettura Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia S. Croce 191 – 30100 Venezia, Italy Abstract gible, especially in the cities of Italy and the rest of Europe. As Carlo Cattaneo (Italian economist, historian and states- This work aims to describe certain landscape ecology man of 19th century) put it so well, they are an enormous concepts applied to the possibility of environmental restora- store of human labor (Rossi 1981). tion and reinstatement, starting from recent studies carried Historical events have threatened to erase these memo- out on land that once underwent Roman centuration. We con- ries, and those that survive can only be interpreted where this sidered an area containing an old quarry, subsequently con- “labor” was most concentrated, as in the case of the Roman verted into a rubbish dump, and applied certain concepts of centuriation of the Veneto and Po valley regions. This great ecology scale, hierarchy and metastability that, together with work of architecture and engineering has become a primary traditional investigations, were able to provide a thorough feature of the territory, a monument strong enough to survive description of the conditions -

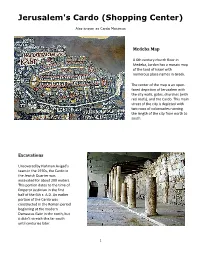

Jerusalem's Cardo (Shopping Center)

Jerusalem's Cardo (Shopping Center) Also known as Cardo Maximus Medeba Map A 6th century church floor in Medeba, Jordan has a mosaic map of the land of Israel with numerous place names in Greek. The center of the map is an open‐ faced depiction of Jerusalem with the city walls, gates, churches (with red roofs), and the Cardo. This main street of the city is depicted with two rows of colonnades running the length of the city from north to south. Excavations Uncovered by Nahman Avigad's team in the 1970s, the Cardo in the Jewish Quarter was excavated for about 200 meters. This portion dates to the time of Emperor Justinian in the first half of the 6th c. A.D. An earlier portion of the Cardo was constructed in the Roman period beginning at the modern Damascus Gate in the north, but it didn't stretch this far south until centuries later. 1 The Main Street The central street of the Cardo is 40 feet (12 m) wide and is lined on both sides with columns. The total width of the street and shopping areas on either side is 70 feet (22 m), the equivalent of a 4‐lane highway today. This street was the main thoroughfare of Byzantine Jerusalem and served both residents and pilgrims. Large churches flanked the Cardo in several places. Shopping Area The columns supported a wooden (no longer preserved) roof that covered the shopping area and protected the patrons from the sun and rain. Today the Byzantine street is about 6 meters below the present street level, indicating the level of accumulation in the last 1400 years. -

Eusebius and Hadrian's Founding of Aelia Capitolina in Jerusalem

ELECTRUM * Vol. 26 (2019): 119–128 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.19.007.11210 www.ejournals.eu/electrum EUSEBIUS AND HADRIAN’S FOUNDING OF AELIA CAPItoLINA IN JERUSALEM Miriam Ben Zeev Hofman Ben Gurion University of the Negev Abstract: From numismatic findings and recent excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem it emerges that the preparatory work on Aelia Capitolina started at the very beginning of Hadrian’ reign, most probably in the 120s, more than a decade before the Bar Kokhba war. The question then arises as how it happened that Eusebius mentions the founding of this colony as a conse- quence of the war. The answer lies both in the source he depends upon, possibly Ariston of Pella, and also in Eusebius’ own conception of Jewish history. Keywords: Bar Kokhba’s coins, Jerusalem excavations, Ariston of Pella, Eusebius’ view of Jewish history. The military colony of Aelia Capitolina which Hadrian founded in Jerusalem constitutes a traumatic event and a turning point in Jewish history. The holy city of Jerusalem turned into a pagan site inhabited by Roman soldiers, where idolatrous shrines were built and pagan religious rites were held. Jews were prohibited from entering it. The meaning of this event has been variously interpreted in modern scholarship,1 and its very timing within the context of the Bar Kokhba war has long been debated in view of the conflicting testimonies provided by the extant sources. At the beginning of the third century CE, Cassius Dio records the founding of the colony as preceding the Bar 1 For example, scholars are found who consider it usual Roman praxis and attribute it to technical and logistical considerations (Bowersock 1980, 134–135, 138; Mildenberg 1980, 332–334; Schäfer 1981, 92; Schäfer 1990, 287–288, 296; Schäfer 2003, 147; see also Tameanko 1999, 21; Bieberstein 2007, 143–144; Bazzana 2010, 98–99), while others contend that the founding was meant to put an end to Jewish expectations of a Temple by founding a miniature Rome explicitly intended for the settlement of foreign races and for- eign religious rites. -

Christmas and Epiphany G E N E R a L E D I T O R Robert B

Christmas and Epiphany G E N E R A L E D I T O R Robert B. Kruschwitz A rt E di TOR Heidi J. Hornik R E V ie W E D I T O R Norman Wirzba PROCLAMATION EDITOR William D. Shiell A S S I S tant E ditor Heather Hughes PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Elizabeth Sands Wise D E S igner Eric Yarbrough P UB li SH E R The Center for Christian Ethics Baylor University One Bear Place #97361 Waco, TX 76798-7361 P H one (254) 710-3774 T oll -F ree ( US A ) (866) 298-2325 We B S ite www.ChristianEthics.ws E - M ail [email protected] All Scripture is used by permission, all rights reserved, and unless otherwise indicated is from New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. ISSN 1535-8585 Christian Reflection is the ideal resource for discipleship training in the church. Multiple copies are obtainable for group study at $3.00 per copy. Worship aids and lesson materials that enrich personal or group study are available free on the Web site. Christian Reflection is published quarterly by The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University. Contributors express their considered opinions in a responsible manner. The views expressed are not official views of The Center for Christian Ethics or of Baylor University. The Center expresses its thanks to individuals, churches, and organizations, including the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, who provided financial support for this publication. -

Aelia Capitolina’ Through a Review of the Archaeological Data

Roman changes to the hill of Gareb in ‘Aelia Capitolina’ through a review of the archaeological data Roberto Sabelli Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Firenze Abstract opposite page Following Jewish revolts, in 114-117 and 132-136 AD, the colony of Iulia Aelia Cap- Fig.1 itolina was founded by Publio Elio Traiano Adriano on the site of Jerusalem – View of the east side Aelia in his honour and Capitolina because it was intended to contain a Capi- of the old walled city from Kidron Valley tol for the Romans – so as to erase Jewish and Christian memories. On the ba- (R. Sabelli 2007) sis of the most recent research it is possible to reconstruct the main phases of transformation by the Romans of a part of the hill of Gareb: from a stone quar- ry (tenth century BC - first century AD) into a place of worship, first pagan with the Hadrianian Temple (second century AD) then Christian with the Costantin- ian Basilica (fourth century AD). Thanks to the material evidence, historical tes- timonies, and information on the architecture of temples in the Hadrianic pe- riod, we attempt to provide a reconstruction of the area where the pagan tem- ple was built, inside the expansion of the Roman town in the second century AD, aimed at the conservation and enhancement of these important traces of the history of Jerusalem. 1 The Gehenna Valley (Wadi er-Rababi to- The hill of Gareb in Jerusalem to the north of Mount Zion, bounded on the day) was for centuries used as city ity 1 dump and for disposing of the unburied south and west by the Valley of Gehenna (Hinnom Valley) , rises to 770 me- corpses of delinquents, which were then ters above sea level; its lowest point is at its junction with the Kidron Valley, burned. -

RCI Demolition and Relocation Timeline by Emily Tower Priority for On-Post Housing, Wagner Said

School is now in session. Drive carefully. ® VOL. 65, NO. 31 SERVING THE COMMUNITY OF THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AT WEST POINT AUGUST 15, 2008 RCI demolition and relocation timeline By Emily Tower priority for on-post housing, Wagner said. Coming up with a plan wasn’t Most West Point personnel easy, but West Point Family transfer in and out during the Housing officials now know a summer, and that provides enough timeline for construction that will predictability for Wagner to feel demolish and rebuild some homes comfortable about moving each and renovate others into more Stony Lonesome I Family into modern houses, the housing project another on-post house, but he cannot director said last week. guarantee that. “It’s exciting to get going after “I don’t know how exactly the planning for a year,” Rich Wagner, housing will work out,” he said. the Balfour Beatty Communities “But (Stony Lonesome I Families) project director for West Point will get No. 1 priority to move on Family Housing, LLC, said Aug. post. I believe we will have enough 8. housing because of the summer Over the next eight years, move next year, but I can’t promise various levels of construction a house.” Jefferson Hall opens Wednesday will turn 961 on-post homes into West Point leadership and leaders The new six-story Jefferson Hall Library and Learning Center opens Wednesday with a brief 824 new or refurbished homes, from Balfour Beatty Communities informal ceremony at 8:30 a.m. open to the West Point community with tours to follow. -

Petra, Jordan August 31-Sept 2, 2021

“Travel with Gina” . is NOT a typical tour. You are a friend “Traveling with Me” the way I like to travel. We see the important sights & the real local culture - safely. Due to the ongoing impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19), protecting the safety and wellbeing of travelers, local guides, and suppliers remains my priority and I have adjusted my flexible cancellation and change policy to accommodate the changing times. These trips are good for people who are independent travelers wanting some free time when they travel with a “group of friends”. Not every 5 minutes is planned. We have a lot of free time for individual interests. Many of the people who join this group trip become “lifelong friends” because you have so much in common. Not everyone in our life loves to travel so we need these “traveller friends”. These trips are also for people who want longer, extended & cultural travel. Maybe you are retired already or preparing for retirement? Maybe you want a lifestyle & work-life that allows you to travel as much as you want at any age? Welcome to “Travel with Gina”! “Travel with Gina” PETRA & WADI RUM TOUR 3-Day Tour From Jerusalem August 31-Sept 2, 2021 (3 days) Land Price: $900 (A Gina tour organized with Abraham Hostels) + Int’l Air Starting at $700 TRIP HIGHLIGHTS: • Explore one of the Seven Wonders of the World Petra, the jewel of Jordan, the lost city of the biblical Nabateans, one of the New Seven Wonders of the World – Petra is a magical hand-carved wonder built in the sixth century BC. -

Holy Land Classic October 27 - November 5, 2021

Join Pastor Phil Heinze Holy Land Classic October 27 - November 5, 2021 For information or to make a reservation contact: Kathy Humen - Personalized Travel, LLC [email protected] | 817-773-6527 Oct. 27 & 28 - USA to the Holy Land Your pilgrimage begins as you depart the USA on an overnight flight. You will be welcomed at the Tel Aviv airport by our representative and transferred to your hotel to enjoy dinner before retiring for the night. (D) Oct. 29 - The Galilee Worship as you sail across the Sea of Galilee. Visit Capernaum, center of Jesus’ ministry in the Galilee, and visit the synagogue built on the site where Jesus taught (Matt.4:13, 23). On the Mount of Beatitudes, contemplate the “Sermon on the Mount” (Matt. 5-7). Explore the Church of the Fish and the Loaves at Tabgha, traditional site of the feeding of the 5,000 (Luke 9:10). See the Chapel of the Primacy, where Peter professed his devotion three times to the risen Christ (John 21). In Magdala, once home to Mary Magdalene, visit a recently discovered first-century synagogue. Recall Jesus’ baptism by John the Baptist at the Jordan River. (B,D) Oct. 30 - Cana, Nazareth, Megiddo & Caesarea Visit the Franciscan Wedding Chapel in Cana, site of Jesus’ first miracle, before continuing on to Nazareth, Jesus’ boyhood home (Matthew 2:23). Look out over Tel Megiddo (Armageddon) to view one of the most important archaeological sites in Israel. Today’s last stop is Caesarea, a center of the early Christians where an angel visited Cornelius, the first Gentile believer (Acts 10), and where Paul was imprisoned for two years before appealing to Caesar. -

Roman Centuriation in Satellite Images Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

Roman Centuriation in Satellite Images Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. Roman Centuriation in Satellite Images. Philica, Philica, 2015, 10.5281/zenodo.3361974. hal-02264427 HAL Id: hal-02264427 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02264427 Submitted on 7 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. DOI 10.5281/zenodo.3361974 Roman Centuriation in Satellite Images Amelia Carolina Sparavigna (Department of Applied Science and Technology, Politecnico di Torino) Published in enviro.philica.com Abstract The satellite images of Google Earth can show us how the Roman divided the land in their colonies, according to the surveying system of Centuriation. Keywords: Satellite images, Google Earth, Centuriation. Centuriation is the surveying system used in the Roman world to divide the land to be used by Roman settlers, which were sent in the conquered territories for military or demographic reasons [1]. This division of the territory was based on parallel and perpendicular lines which were called “decumani” and “kardines”. The decumani were usually arranged along the larger part of the territory, or were parallel to a public main road. Decumani and kardines were the "limites" of the land, and "limitatio" was synonymous with land division. -

The Coins of Aelia Capitolina

Top of the Damascus Gate. (Detail of a photo in Wikimedia Commons by Laurice Haddad) N 2018 Donald Trump, the president of called Aelia Capitolina and no Jews lived (Jupiter), parts of which still stand. In Ithe United States of America, ordered there. From the reign of the Roman 130 AD he visited Jerusalem and it was that his country officially recognize Jeru- Em peror Hadrian (117-138 AD) to the from that time that the city was rebuilt salem as the capital of Israel. Following reign of Hostilian (251 AD) a number of as a Roman colony which Hadrian called the United States the Australian gov - coins were minted bearing the name Aelia Capitolina. His family name was ernment ordered that West Jerusalem Aelia Capitolina, and the coins reflect the Aelius, and Capitolina referred to the be recognized by Australia as the capi - Greco-Roman culture that existed in the gods worshiped on the Capitoline Hill tal of Israel. Not many Australians know city at that time. in Rome. Coins were struck to celebrate that for some centuries after the Second Jesus Christ was crucified in Jerusalem the foundation of Aelia Capitolina. ( Fig - Jewish Revolt (132-135 AD) the city was in 30 AD. The city that he knew was ures 1 and 2 ) Veterans of the Roman de stroyed by a Roman army in 70 AD army and other non-Jewish people were after the First Jewish Revolt (66-70 AD). settled there. Jews were not allowed The temple that King Herod built in to live in the city and circumcision was Jerusalem was demolished but the great forbidden.