On the Lost Circus of Aelia Capitolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerusalem in Classical Ages: a Critical Review

Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 14, No 2, pp. 139-154 Copyright © 2014 MAA Printed in Greece. All rights reserved. JERUSALEM IN CLASSICAL AGES: A CRITICAL REVIEW Sultan Abdullah Ma'ani1, Abd alrzaq Al-Maani 2, Mohammed Al-Nasarat2 1Queen Rania Institute of Tourism and Heritage, Hashemite University, Jordan 2Department of History, Al-Hussein Bin Talal University, Ma’an, Jordan Received: 07/10/2013 Accepted: 06/12/2013 Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study is a review and in several cases it sheds light upon the history of Jerusalem City during the Roman and Byzantine epochs through focusing on a) the demography of the city, b) the names which had been mentioned in historical sources, c) ancient inscrip- tions and d) its urban design. The review goes through Jewish sources, particularly those which deal with the reign of the Roman leader, Pompey (Pompey the Great) and the Maccabees (Machabees); the reign of the Roman Emperor, Titus, during which the Jews were tortured; the reign of the Roman king of Jews, Herod (or Herod the Great); the reign of the Roman Emperor, Ha- drian; and the converting of the City from paganism to Christianity. KEYWORDS: Jerusalem, Roman epoch, Byzantine epoch, Hasmonean dynasty, historical sources, inscriptions. 140 MA'ANI et al 1. DEMOGRAPHY OF THE CITY The Jewish historian, Josephus, said that Herod built in the City a sports stadium and Jerusalem is a city fenced with valleys, a horse-racing hippodrome (Al-Fanny, 2007, situated above a mountains range in Central p.15). Palestine. This range extends between the Jerusalem, as the other big cities of Pales- Palestinian coast to the west and the Negev tine and Syria, uses the Latin language as an desert to both the east and south. -

Betar and Aelia Capitolina: Symbols of Jewish Suffering Dr

Betar and Aelia Capitolina: Symbols of Jewish Suffering Dr. Jill Katz Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology, Yeshiva University Of the five specific tragedies that warrant fasting on Tishah b’Av (Mishnah Taanit 4:6), two are related to the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome. The first is the capture of the city of Betar (135 CE) and the second is the plowing of Jerusalem one year later. At first glance, these calamities do not seem to be of the same scale as the destruction of the First and Second Temples. The Jews were neither forcibly removed en masse to a distant land nor was a standing Temple destroyed. Perhaps one could argue that their inclusion within the list was simply due to their still being fresh in people’s memories. Surely, the rabbis of the Mishnaic period would have encountered eyewitnesses to these events and been moved by their recollections. Yet, if this were so, then the Mishnah really need only include one reference to the rebellion. By including two, the Mishnah is teaching us something about the magnitude of this tragedy and the challenges that lay ahead for the Jewish people. Betar If not for the Bar Kokhba rebellion, it is unlikely many people would be familiar with Betar. The ancient city (Khirbet el-Yahud – “ruin of the Jews”) was a modest settlement southwest of Jerusalem in the Judean Hills. Surveys and brief excavations have demonstrated that Betar was first settled during the period of the Shoftim and became a city of moderate importance by the time of Hizkiyahu. -

CALVARY CHAPEL HONOLULU TOUR of ISRAEL Saturday, November 2 – Friday, November 15, 2019

CALVARY CHAPEL HONOLULU TOUR OF ISRAEL Saturday, November 2 – Friday, November 15, 2019 Register online at www.inspiredtravel.com/hon19 Send a check payable to: Day Tour Date Proposed Itinerary Hotels Inspired Travel 3000 W. MacArthur Blvd. #450 Santa Ana, CA 92704 Day 1 Sat 2-Nov Depart USA on your overnight flight to Tel Aviv Night on Plane Please include IT HONLU19IS on all checks and correspondence. Day 2 Sun 3-Nov Arrive in Tel Aviv, transfer to hotel Crowne Plaza, Jerusalem Estimated price of *$4798 from Honolulu, HI, per person, double occupancy includes: Round-trip Day 3 Mon 4-Nov Mount of Olives, Palm Sunday Road, Garden of Gethsemane, Crowne Plaza, Jerusalem airfare to Tel Aviv on a scheduled carrier, 11 days touring the sites listed in Israel, First Class Southern Steps, City of David (Jeremiah's Cistern, Hezekiah's hotels with breakfast and dinner daily plus one lunch, and all transfers, entrance fees, taxes and Tunnel, Pool of Siloam), Western Wall Tunnels, Yad Vashem (Holocaust Museum) tips to hotels, drivers and guides. (Land Only price of *$3113 per person, double occupancy includes: all accommodations except airfare and airport transfers) Day 4 Tue 5 - Nov Wailing Wall, Ophel Digs, Southern Steps, Jewish Quarter, Burnt Crowne Plaza, Jerusalem House, Cardo, Hezekiah's Wall, Arab Market, Jaffa Gate, Elah A deposit of $400 per person is due at registration in order to secure your spot on this Valley tour. All registrations will be processed on a space-available basis. A second deposit of 50% of Day 5 Wed 6-Nov View Bethlehem and Shepherds' Fields, remainder of the day free Crowne Plaza, Jerusalem the tour costs and a copy of your passport will be due by May 2, 2019. -

Jerusalem's Cardo (Shopping Center)

Jerusalem's Cardo (Shopping Center) Also known as Cardo Maximus Medeba Map A 6th century church floor in Medeba, Jordan has a mosaic map of the land of Israel with numerous place names in Greek. The center of the map is an open‐ faced depiction of Jerusalem with the city walls, gates, churches (with red roofs), and the Cardo. This main street of the city is depicted with two rows of colonnades running the length of the city from north to south. Excavations Uncovered by Nahman Avigad's team in the 1970s, the Cardo in the Jewish Quarter was excavated for about 200 meters. This portion dates to the time of Emperor Justinian in the first half of the 6th c. A.D. An earlier portion of the Cardo was constructed in the Roman period beginning at the modern Damascus Gate in the north, but it didn't stretch this far south until centuries later. 1 The Main Street The central street of the Cardo is 40 feet (12 m) wide and is lined on both sides with columns. The total width of the street and shopping areas on either side is 70 feet (22 m), the equivalent of a 4‐lane highway today. This street was the main thoroughfare of Byzantine Jerusalem and served both residents and pilgrims. Large churches flanked the Cardo in several places. Shopping Area The columns supported a wooden (no longer preserved) roof that covered the shopping area and protected the patrons from the sun and rain. Today the Byzantine street is about 6 meters below the present street level, indicating the level of accumulation in the last 1400 years. -

Eusebius and Hadrian's Founding of Aelia Capitolina in Jerusalem

ELECTRUM * Vol. 26 (2019): 119–128 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.19.007.11210 www.ejournals.eu/electrum EUSEBIUS AND HADRIAN’S FOUNDING OF AELIA CAPItoLINA IN JERUSALEM Miriam Ben Zeev Hofman Ben Gurion University of the Negev Abstract: From numismatic findings and recent excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem it emerges that the preparatory work on Aelia Capitolina started at the very beginning of Hadrian’ reign, most probably in the 120s, more than a decade before the Bar Kokhba war. The question then arises as how it happened that Eusebius mentions the founding of this colony as a conse- quence of the war. The answer lies both in the source he depends upon, possibly Ariston of Pella, and also in Eusebius’ own conception of Jewish history. Keywords: Bar Kokhba’s coins, Jerusalem excavations, Ariston of Pella, Eusebius’ view of Jewish history. The military colony of Aelia Capitolina which Hadrian founded in Jerusalem constitutes a traumatic event and a turning point in Jewish history. The holy city of Jerusalem turned into a pagan site inhabited by Roman soldiers, where idolatrous shrines were built and pagan religious rites were held. Jews were prohibited from entering it. The meaning of this event has been variously interpreted in modern scholarship,1 and its very timing within the context of the Bar Kokhba war has long been debated in view of the conflicting testimonies provided by the extant sources. At the beginning of the third century CE, Cassius Dio records the founding of the colony as preceding the Bar 1 For example, scholars are found who consider it usual Roman praxis and attribute it to technical and logistical considerations (Bowersock 1980, 134–135, 138; Mildenberg 1980, 332–334; Schäfer 1981, 92; Schäfer 1990, 287–288, 296; Schäfer 2003, 147; see also Tameanko 1999, 21; Bieberstein 2007, 143–144; Bazzana 2010, 98–99), while others contend that the founding was meant to put an end to Jewish expectations of a Temple by founding a miniature Rome explicitly intended for the settlement of foreign races and for- eign religious rites. -

Hypothesis / Research Question Sources of Study

Gillis and Keating 1 Hypothesis / Research Question Did Byzantine sport and the Constantinople Hippodrome influence modern day sporting events and venues? Sources of Study Primary Figure 1: The Serpent Column depicted three snakes intertwined and was one of three legs holding a gold cauldron and was erected on the spina of the Hippodrome. (Governorship Of Istanbul). Gillis and Keating 2 Figure 2: The walled obelisk stood at the southern end of the Hippodrome (Governorship of Istanbul) Figure 3: The Obelisk of Theodosius. This Obelisk of Theodosius stood in the Hippodrome. (Governorship of Istanbul) Gillis and Keating 3 Figure 4: Picture of one side of the base of the Obelisk of Theodosius. The other side’s depicts the emperor and his family watching chariot races from the imperial box (Governance of Istanbul). Secondary Wells, C. (2006). “Sailing From Byzanthium: How A Lost Empire Shaped The Word” Bantam Dell: New York, New York Guttmann, A. (1981). Sport Spectators from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Journal of Sport History. Vol. 8 No. 2 p. 5‐27 Schrodt, B. (1981). Sports of the Byzantine Empire. Journal of Sport History. Vol. 8, No. 3. Bassett, S. (1991). The Antiquities in the Hippodrome of Constantinople. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 45, 87‐96 Gillis and Keating 4 Guilland, R.(1948). The Hippodrome at Byzantium. Speculum, 23 (4), 676‐682 Sultan Amhed Square. In ‘Governorship of Istanbul’. Retrieved Feb 19 2009 from: http://english.istanbul.gov.tr/Default.aspx?pid=300 Limitations The lack of primary accounts of the hippodrome and it’s sporting culture has affected our research by having interpretations of accounts rather than an un‐interpreted account of detail. -

Story of Judaism - Timeline

Story of Judaism - Timeline God creates the world by speaking; therefore, Hebrew letters have creative power. God of Jews is Creator of the World – not tribal. Creation of Humanity Year 0 Special place to Humans. Two stories. No original sin. Abraham: God chooses Abraham Covenant – promise and contract: the chosen people Moses: Leads people of Israel out of slavery in Egypt Inscription of Merneptah – first mention of Israel in recorded history (1206 BCE) C C BCE th 12 Moses receives the law on Mt Sinai – ten commandments, sacrificial system, other - th commandments 14 Beginning of Judaism King David: Model of king for Israel Kingdom of Israel C C BCE Temple is built (under his son, Solomon) th Sacrifices at the temple – means of forgiveness 10 Centralized political and religious system Assyrians invade and destroy the northern kingdom of Israel They seem to disappear from history 722 BCE Babylon conquers the southern kingdom of Judah. Temple is destroyed Leaders and others taken into exile in Babylon 586 BCE Development of first synagogues – place of prayer and study Return to Jerusalem – gradual Many stay in Babylon for more than 2000 years there is a Jewish community in that region Ezra and Nehemiah are early leaders 520 BCE Temple is gradually rebuilt: it is smaller but sacrifices begin again Political kingdom never becomes as large and powerful as before Seleucid Greeks conquer Israel Desecrate the temple by sacrificing a pig in temple C C BCE Maccabees revolt and expel the Seleucids nd 2 Re-dedication of temple leads to holiday of Chanukah Story of Judaism - Timeline Roman General, Titus, destroys Jerusalem and the 2nd temple What should we do after destruction of temple and Jerusalem? 4 answers: (Josephus, mourn, die, Rabbinic) Beginning of Rabbinic Judaism 70 CE Redefinition of Judaism – no longer sacrifices at temple Rabbis (teachers), Torah, Talmud, Study and Synagogue replace priests, temple and sacrifices. -

Christmas and Epiphany G E N E R a L E D I T O R Robert B

Christmas and Epiphany G E N E R A L E D I T O R Robert B. Kruschwitz A rt E di TOR Heidi J. Hornik R E V ie W E D I T O R Norman Wirzba PROCLAMATION EDITOR William D. Shiell A S S I S tant E ditor Heather Hughes PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Elizabeth Sands Wise D E S igner Eric Yarbrough P UB li SH E R The Center for Christian Ethics Baylor University One Bear Place #97361 Waco, TX 76798-7361 P H one (254) 710-3774 T oll -F ree ( US A ) (866) 298-2325 We B S ite www.ChristianEthics.ws E - M ail [email protected] All Scripture is used by permission, all rights reserved, and unless otherwise indicated is from New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. ISSN 1535-8585 Christian Reflection is the ideal resource for discipleship training in the church. Multiple copies are obtainable for group study at $3.00 per copy. Worship aids and lesson materials that enrich personal or group study are available free on the Web site. Christian Reflection is published quarterly by The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University. Contributors express their considered opinions in a responsible manner. The views expressed are not official views of The Center for Christian Ethics or of Baylor University. The Center expresses its thanks to individuals, churches, and organizations, including the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, who provided financial support for this publication. -

Aelia Capitolina’ Through a Review of the Archaeological Data

Roman changes to the hill of Gareb in ‘Aelia Capitolina’ through a review of the archaeological data Roberto Sabelli Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Firenze Abstract opposite page Following Jewish revolts, in 114-117 and 132-136 AD, the colony of Iulia Aelia Cap- Fig.1 itolina was founded by Publio Elio Traiano Adriano on the site of Jerusalem – View of the east side Aelia in his honour and Capitolina because it was intended to contain a Capi- of the old walled city from Kidron Valley tol for the Romans – so as to erase Jewish and Christian memories. On the ba- (R. Sabelli 2007) sis of the most recent research it is possible to reconstruct the main phases of transformation by the Romans of a part of the hill of Gareb: from a stone quar- ry (tenth century BC - first century AD) into a place of worship, first pagan with the Hadrianian Temple (second century AD) then Christian with the Costantin- ian Basilica (fourth century AD). Thanks to the material evidence, historical tes- timonies, and information on the architecture of temples in the Hadrianic pe- riod, we attempt to provide a reconstruction of the area where the pagan tem- ple was built, inside the expansion of the Roman town in the second century AD, aimed at the conservation and enhancement of these important traces of the history of Jerusalem. 1 The Gehenna Valley (Wadi er-Rababi to- The hill of Gareb in Jerusalem to the north of Mount Zion, bounded on the day) was for centuries used as city ity 1 dump and for disposing of the unburied south and west by the Valley of Gehenna (Hinnom Valley) , rises to 770 me- corpses of delinquents, which were then ters above sea level; its lowest point is at its junction with the Kidron Valley, burned. -

RCI Demolition and Relocation Timeline by Emily Tower Priority for On-Post Housing, Wagner Said

School is now in session. Drive carefully. ® VOL. 65, NO. 31 SERVING THE COMMUNITY OF THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AT WEST POINT AUGUST 15, 2008 RCI demolition and relocation timeline By Emily Tower priority for on-post housing, Wagner said. Coming up with a plan wasn’t Most West Point personnel easy, but West Point Family transfer in and out during the Housing officials now know a summer, and that provides enough timeline for construction that will predictability for Wagner to feel demolish and rebuild some homes comfortable about moving each and renovate others into more Stony Lonesome I Family into modern houses, the housing project another on-post house, but he cannot director said last week. guarantee that. “It’s exciting to get going after “I don’t know how exactly the planning for a year,” Rich Wagner, housing will work out,” he said. the Balfour Beatty Communities “But (Stony Lonesome I Families) project director for West Point will get No. 1 priority to move on Family Housing, LLC, said Aug. post. I believe we will have enough 8. housing because of the summer Over the next eight years, move next year, but I can’t promise various levels of construction a house.” Jefferson Hall opens Wednesday will turn 961 on-post homes into West Point leadership and leaders The new six-story Jefferson Hall Library and Learning Center opens Wednesday with a brief 824 new or refurbished homes, from Balfour Beatty Communities informal ceremony at 8:30 a.m. open to the West Point community with tours to follow. -

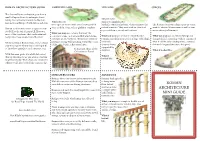

Roman Architecture Mini Guide

ROMAN ARCHITECTURE GUIDE AMPHITHEATRE THEATRE CIRCUS The Ancient Rome civilization grew from a small village in Rome to an Empire domi- Theatres were nating vast territories around the Mediter- similar to Amphitheatres ranean Sea in Europe, North Africa and Asia. Amphitheatres but had a semicircular form, which enhances the The Roman circus was a large open-air venue were open air venues with raised seating which natural acoustics. They were used for theatrical used for chariot & horse races as well as com- Roman Architecture covers the period from were used for event such as gladiator combats. representation, concerts and orations. memoration performances. 509 BCE to the 4th Century CE. However, most of the structures, that can be admired What you may see: remains that look like What you may see: similar to Amphitheatres What you may see: an extremely large and today dates from around 100 CE or later. concentric stairs ; a downward hill which forms a circular or an oval basin ; Remains of arches or remains; raised flat area used as a stage with a high elongated field ; encircling walls or remains of back wall what look like stairs (seating area) ; a central When looking at Roman ruins, it’s not always passages ; strong walls pointing toward the center (scaenae frons) thin and elongated structure (the spina). easy to recognize what you are looking at & of the basin ; a flat central area. supported by to know how grandiose such structure was. In that case, think of the columns. What it looked like : Colosseum in Rome! With this mini guide, it is a little bit easier! What it The top drawing shows you what a structure looked like : might look today. -

A Contemporary View of Ancient Factions: a Reappraisal

A Contemporary View of Ancient Factions: A Reappraisal by Anthony Lawrence Villa Bryk A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of Classical Studies University of Michigan Spring 2012 i “Ab educatore, ne in circo spectator Prasianus aut Venetianus neve parmularius aut scutarius fierem, ut labores sustinerem, paucis indigerem, ipse operi manus admoverem, rerum alienarum non essem curiosus nec facile delationem admitterem.” “From my governor, to be neither of the green nor of the blue party at the games in the Circus, nor a partizan either of the Parmularius or the Scutarius at the gladiators' fights; from him too I learned endurance of labour, and to want little, and to work with my own hands, and not to meddle with other people's affairs, and not to be ready to listen to slander.” -Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 1.5 © Anthony Lawrence Villa Bryk 2012 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor David S. Potter for his wisdom, guidance, and patience. Professor Potter spent a great deal of time with me on this thesis and was truly committed to helping me succeed. I could not have written this analysis without his generous mentoring, and I am deeply grateful to him. I would also like to thank Professor Netta Berlin for her cheerful guidance throughout this entire thesis process. Particularly, I found her careful editing of my first chapter immensely helpful. Also, Professor Sara Ahbel-Rappe’s Pagans and Christians seminar was essential to my foundational understanding of this subject. I also thank her for being a second reader on this paper and for suggesting valuable revisions.