Shell Keeps-Catalogue1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castle Designs Through History: from Simple Mounds to Strong Towers

https://www.exploring-castles.com/castle_designs/ Castle Designs Through History: From Simple Mounds to Strong Towers Castle designs have changed over history. This is because of changes in technology over time – as well as changes to the function and purpose of castles. The first castles were simply ‘mounds’ of earth, and medieval castle designs improved on these basics – adding ditches in the Motte & Bailey design. As technology advanced – and as attackers got more sophisticated – elaborate concentric castle designs emerged, creating a fortress almost impregnable to its enemies. Nowadays, castles are designed for prestige, for fantasy, and to embellish a romantic view of the life of kings, queens and nobles from years gone by. This page gives a brief overview of the history of castles, and explains why different castle designs came about. Fundamentally, these changing designs were due to the changes in the purpose and significance of castles. Early Medieval Times From Norman Times: Motte & Bailey Castles – Simple designs that were quick to build The first castles, built in the Early Middle Ages (early Medieval period), were ‘earthworks’ – mounds of earth primarily built for defence, as enemies struggled to climb them. During the 1000s, the Normans developed these into Motte and Bailey castle designs. Effectively, a ‘Motte’ was a large mound of earth, and a ‘Bailey’ was the flattened area beside the mound. The ‘Motte’ could be surrounded with a ditch, and buildings could be placed on the bailey – made of timber or, if time permitted, stone. The key benefit of Motte & Bailey castles was that they were very quick to build, but pretty difficult to attack. -

Shell Keeps-Catalogue1

Shell-keeps - The Catalogue Fig. 1. Plan of Berkeley Castle prepared for G. T Clark, published in Vol. 1 of Mediaeval Military Architecture, 1884, opposite. p. 229. Berkeley 2. Berkeley er (knocking out an earlier “bastion”) comprising two, Published interpretations of the shell-keep have as- joined rectangular towers which may be an early ex- sumed the following sequence: (a) the motte was part ample of an artillery emplacement and (ii) additions of the castle of William fitzOsbern, documented in and alterations to the forebuilding and (iii) encasement the late 11th century, bearing a structure of which no of the south “bastion” by the new gatehouse to the trace now remains; (b) with the assent and direction inner bailey (e) the siege of 1645 and the slighting of of Henry II in 1154, the new owner, Robert fitzHard- 1646 inflicted damage to the motte and its masonry ing (a rich Bristol merchant, from an English family, structures which were patched up around 1700 (f) who supported the Angevin cause and died in 1170) various 18th- to 20th-century alterations and additions truncated the motte-top, encased the motte in a shell- further masked and/or destroyed the structures, both in keep with battered plinth, a series of pilaster buttress- the domestic ranges (the east range of which is wholly es, (probably) four semi-circular “bastions” and (soon 1920s, as is the rebuilding of the chapel) and in Thor- afterwards) a forebuilding with defended stair rising pe's Tower. from ground level to a doorway on the motte-top, the The castle is unusual in having charter evidence latter being leveled up with the spoil created by relating to its revival under new ownership in the truncating the motte; (c) this shell-keep rose above 1150s, although the authenticity of these charters as the motte, with domestic buildings against its inside contemporary record has been questioned. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

826 INDEX 1066 Country Walk 195 AA La Ronde

© Lonely Planet Publications 826 Index 1066 Country Walk 195 animals 85-7, see also birds, individual Cecil Higgins Art Gallery 266 ABBREVIATIONS animals Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum A ACT Australian Capital books 86 256 A La RondeTerritory 378 internet resources 85 City Museum & Art Gallery 332 abbeys,NSW see New churches South & cathedrals Wales aquariums Dali Universe 127 Abbotsbury,NT Northern 311 Territory Aquarium of the Lakes 709 FACT 680 accommodationQld Queensland 787-90, 791, see Blue Planet Aquarium 674 Ferens Art Gallery 616 alsoSA individualSouth locations Australia Blue Reef Aquarium (Newquay) Graves Gallery 590 activitiesTas 790-2,Tasmania see also individual 401 Guildhall Art Gallery 123 activitiesVic Victoria Blue Reef Aquarium (Portsmouth) Hayward Gallery 127 AintreeWA FestivalWestern 683 Australia INDEX 286 Hereford Museum & Art Gallery 563 air travel Brighton Sea Life Centre 207 Hove Museum & Art Gallery 207 airlines 804 Deep, The 615 Ikon Gallery 534 airports 803-4 London Aquarium 127 Institute of Contemporary Art 118 tickets 804 National Marine Aquarium 384 Keswick Museum & Art Gallery 726 to/from England 803-5 National Sea Life Centre 534 Kettle’s Yard 433 within England 806 Oceanarium 299 Lady Lever Art Gallery 689 Albert Dock 680-1 Sea Life Centre & Marine Laing Art Gallery 749 Aldeburgh 453-5 Sanctuary 638 Leeds Art Gallery 594-5 Alfred the Great 37 archaeological sites, see also Roman Lowry 660 statues 239, 279 sites Manchester Art Gallery 658 All Souls College 228-9 Avebury 326-9, 327, 9 Mercer Art Gallery -

English Heritage Og Middelalderborgen

English Heritage og Middelalderborgen http://blog.english-heritage.org.uk/the-great-siege-of-dover-castle-1216/ Rasmus Frilund Torpe Studienr. 20103587 Aalborg Universitet Dato: 14. september 2018 Indholdsfortegnelse Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Indledning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Problemstilling ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Kulturarvsdiskussion ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Diskussion om kulturarv i England fra 1980’erne og frem ..................................................................... 5 Definition af Kulturarv ............................................................................................................................... 6 Hvordan har kulturarvsbegrebet udviklet sig siden 1980 ....................................................................... 6 Redegørelse for Historic England og English Heritage .............................................................................. 11 Begyndelsen på den engelske nationale samling ..................................................................................... 11 English -

Chapter 3: the Finds

Chapter 3: The Finds THE MEDIEVAL AND POST-MEDIEVAL A draft report on the pottery from the 1984 POTTERY (FIGS 3.1-11) excavations was written by Maureen Mellor in the by Cathy Keevill 1980s. The primary aim of the further analysis was to refine the site chronology and to understand the Summary development of the site. This involved adding in the An assemblage of 6779 sherds was recovered from pottery recovered from the 1988-1991 excavations, stratified contexts. The majority of these (a total of amending the context dates derived from the assoc 6317 or 93%) were medieval. This is the first iated pottery where necessary, and checking on the stratified sequence from Witney and as such is dating for the main types within the assemblage in highly important for the understanding of the order to establish a chronology that would corres development of 12th-century and early-13th-century pond to the Oxfordshire pottery sequence. Under pottery traditions in West Oxfordshire. The most standing the development of the major local fabric interesting feature of the assemblage was the range and vessel traditions in west Oxfordshire was also a of imported material from other regions, particularly priority, especially the calcareous gravel-tempered south-western England. These included fabric types fabric (Witney Fabric 1), which is similar to types in from Minety, Wiltshire (Fabrics 9 and 37), from the Cotswolds (Mellor 1994,72) and at Oxford (fabric Laverstock, south Wiltshire (Fabrics 5 and 25), types OXAC). known in Bath and Trowbridge (fabric 23), Newbury The analysis also included a consideration of the (Fabrics 2 and 3), Winchester (Fabric 8), and a status of the site (and of different areas within the possible Nash Hill product (Fabric 33). -

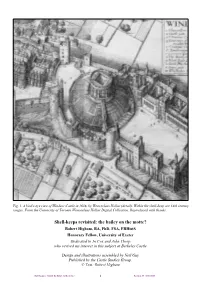

Shell Keeps at Carmarthen Castle and Berkeley Castle

Fig. 1. A bird's-eye view of Windsor Castle in 1658, by Wenceslaus Hollar (detail). Within the shell-keep are 14th century ranges. From the University of Toronto Wenceslaus Hollar Digital Collection. Reproduced with thanks. Shell-keeps revisited: the bailey on the motte? Robert Higham, BA, PhD, FSA, FRHistS Honorary Fellow, University of Exeter Dedicated to Jo Cox and John Thorp, who revived my interest in this subject at Berkeley Castle Design and illustrations assembled by Neil Guy Published by the Castle Studies Group. © Text: Robert Higham Shell-keeps re-visited: the bailey on the motte? 1 Revision 19 - 05/11/2015 Fig. 2. Lincoln Castle, Lucy Tower, following recent refurbishment. Image: Neil Guy. Abstract Scholarly attention was first paid to the sorts of castle ● that multi-lobed towers built on motte-tops discussed here in the later 18th century. The “shell- should be seen as a separate form; that truly keep” as a particular category has been accepted in circular forms (not on mottes) should be seen as a academic discussion since its promotion as a medieval separate form; design by G.T. Clark in the later 19th century. Major ● that the term “shell-keep” should be reserved for works on castles by Ella Armitage and A. Hamilton mottes with structures built against or integrated Thompson (both in 1912) made interesting observa- with their surrounding wall so as to leave an open, tions on shell-keeps. St John Hope published Windsor central space with inward-looking accommodation; Castle, which has a major example of the type, a year later (1913). -

Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-8-2020 "The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812 Joseph R. Miller University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Joseph R., ""The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3208. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3208 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE MEN WERE SICK OF THE PLACE”: SOLDIER ILLNESS AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE WAR OF 1812 By Joseph R. Miller B.A. North Georgia University, 2003 M.A. University of Maine, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2020 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Liam Riordan, Professor of History Kathryn Shively, Associate Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University James Campbell, Professor of Joint, Air War College, Brigadier General (ret) Michael Robbins, Associate Research Professor of Psychology Copyright 2020 Joseph R. -

The Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain

www.e-rara.ch The architectural antiquities of Great Britain Britton, J. London, 1807-1826 ETH-Bibliothek Zürich Shelf Mark: Rar 9289 Persistent Link: http://dx.doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-46826 Index [...]. www.e-rara.ch Die Plattform e-rara.ch macht die in Schweizer Bibliotheken vorhandenen Drucke online verfügbar. Das Spektrum reicht von Büchern über Karten bis zu illustrierten Materialien – von den Anfängen des Buchdrucks bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. e-rara.ch provides online access to rare books available in Swiss libraries. The holdings extend from books and maps to illustrated material – from the beginnings of printing to the 20th century. e-rara.ch met en ligne des reproductions numériques d’imprimés conservés dans les bibliothèques de Suisse. L’éventail va des livres aux documents iconographiques en passant par les cartes – des débuts de l’imprimerie jusqu’au 20e siècle. e-rara.ch mette a disposizione in rete le edizioni antiche conservate nelle biblioteche svizzere. La collezione comprende libri, carte geografiche e materiale illustrato che risalgono agli inizi della tipografia fino ad arrivare al XX secolo. Nutzungsbedingungen Dieses Digitalisat kann kostenfrei heruntergeladen werden. Die Lizenzierungsart und die Nutzungsbedingungen sind individuell zu jedem Dokument in den Titelinformationen angegeben. Für weitere Informationen siehe auch [Link] Terms of Use This digital copy can be downloaded free of charge. The type of licensing and the terms of use are indicated in the title information for each document individually. For further information please refer to the terms of use on [Link] Conditions d'utilisation Ce document numérique peut être téléchargé gratuitement. Son statut juridique et ses conditions d'utilisation sont précisés dans sa notice détaillée. -

BGAS Library Books Available for Sale

BGAS Library Books Available for Sale The Library Committee has completed the recent review of holdings and can offer the following volumes to members for a donation to the Society. Please contact Louise Hughes by Friday 7th April 2017 if interested. Duplicate Copies Anon, Rescue Archaeology in the Bristol Area: 1: Roman, Medieval and later research organised by the City of Bristol Museum & Art Gallery: Monograph No. 2 (Bristol, 1979) Bellows, E. (ed.), John Bellows: Letters and Memoir (London, 1904) Bettey, J. (ed.), Historic Churches & Church Life in Bristol: Essays in Memory of Elizabeth Ralph 1911 – 2000 (Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 2001) Blake, S., Cheltenham's Churches and Chapels A.D.733-1883 (Cheltenham Borough Council Art Gallery and Museum Service, 1979) [pamphlet] Blake, S., Views of Cheltenham: Topographical prints of a Regency Town (Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museums, 1984) [pamphlet] Evans, J. T. (ed.), The Church Plate of Gloucestershire (Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 1906) George, E. & S., Guide to the Probate Inventories of the Bristol Deanery of the Diocese of Bristol (1542-1804) (Bristol Record Society/ Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 1988) Grundy, G. B., Saxon Charters and Field Names of Gloucestershire Parts I & 2 (Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 1936) [two copies] Hart, G. W., Parish Church of St. Mary, Cheltenham (undated) [pamphlet] Holbrook, N. & J. Juřica (eds.), Twenty-Five Years of Industrial Archaeology in Gloucestershire: A Review of New Discoveries and New Thinking in Gloucestershire, South Gloucestershire and Bristol 1979 – 2004 (Cotswold Archaeology, 2003) Kirby, I. M., Diocese of Bristol: A Catalogue of the Records of the Bishop and Archdeacons and of the Dean and Chapter (Bristol, 1970) MacKechnie-Jarvis, J., A History of the Gloucester Diocesan Advisory Committee 1919-1992 (Gloucester Diocesan Advisory Committee, 1992) Mortimer, R. -

Jedburgh Abbey Church: the Romanesque Fabric Malcolm Thurlby*

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 125 (1995), 793-812 Jedburgh Abbey church: the Romanesque fabric Malcolm Thurlby* ABSTRACT The choir of the former Augustinian abbey church at Jedburgh has often been discussed with specific reference to the giant cylindrical columns that rise through the main arcade to support the gallery arches. This adaptation Vitruvianthe of giant order, frequently associated with Romsey Abbey, hereis linked with King Henry foundationI's of Reading Abbey. unusualThe designthe of crossing piers at Jedburgh may also have been inspired by Reading. Plans for a six-part rib vault over the choir, and other aspects of Romanesque Jedburgh, are discussed in association with Lindisfarne Priory, Lastingham Priory, Durham Cathedral MagnusSt and Cathedral, Kirkwall. The scale church ofthe alliedis with King David foundationI's Dunfermlineat seenis rivalto and the Augustinian Cathedral-Priory at Carlisle. formee e choith f Th o rr Augustinian abbey churc t Jedburgha s oftehha n been discussee th n di literature on Romanesque architecture with specific reference to the giant cylindrical columns that rise through the main arcade to support the gallery arches (illus I).1 This adaptation of the Vitruvian giant order is most frequently associated with Romsey Abbey.2 However, this association s problematicai than i e gianl th t t cylindrical pie t Romsea r e th s use yi f o d firse y onlth ba t n yi nave, and almost certainly post-dates Jedburgh. If this is indeed the case then an alternative model for the Jedburgh giant order should be sought. Recently two candidates have been put forward. -

The Norman Conquest Learning Objective: to Understand Chronology, Sources and Factors Through the History of the Norman Conquest of England

Year 7) Term 2A: The Norman Conquest Learning objective: To understand chronology, sources and factors through the history of the Norman Conquest of England. What do I need to know about William and his coronation as king? KEYWORDS: • The coronation of William of Normandy on Christmas Day 1066. Chronology = events put in the • How Anglo-Saxon people reacted to the new Norman king. order that they happened. • What William wanted to do next. Sources = evidence from the past. What do I need to know about the Norman Conquest? Interpretations = a persons • How William created a Feudal System hierarchy. opinion on a historical event. • How William used the Domesday Book to collect information. Key events/people: • How William created Motte & Bailey Castles to scare the English. William the Conqueror/William • How the Bayeux Tapestry controlled history. of Normandy The Feudal System What do I need to know about the Harrying of the North? The Domesday Book • Why William decided to launch an attack on the North. Motte & Bailey Castles • What tactics William used when attacking the North. The Bayeux Tapestry • How England changed under the reign of William of Normandy. The Harrying of the North 25 December 1066 AD 1067-86 AD 1069 AD William is coroneted as Motte & Bailey castles are created and William launches an assault on the Northern rebels: The King of England. the Domesday Book is completed. Harrying of the North begins and ends. What first-order concepts do I need to learn below? Hint: remember! A first-order concept is a word historians use to describe facts related to events.