Status Symbols: Royal and Lordly Residence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castle Designs Through History: from Simple Mounds to Strong Towers

https://www.exploring-castles.com/castle_designs/ Castle Designs Through History: From Simple Mounds to Strong Towers Castle designs have changed over history. This is because of changes in technology over time – as well as changes to the function and purpose of castles. The first castles were simply ‘mounds’ of earth, and medieval castle designs improved on these basics – adding ditches in the Motte & Bailey design. As technology advanced – and as attackers got more sophisticated – elaborate concentric castle designs emerged, creating a fortress almost impregnable to its enemies. Nowadays, castles are designed for prestige, for fantasy, and to embellish a romantic view of the life of kings, queens and nobles from years gone by. This page gives a brief overview of the history of castles, and explains why different castle designs came about. Fundamentally, these changing designs were due to the changes in the purpose and significance of castles. Early Medieval Times From Norman Times: Motte & Bailey Castles – Simple designs that were quick to build The first castles, built in the Early Middle Ages (early Medieval period), were ‘earthworks’ – mounds of earth primarily built for defence, as enemies struggled to climb them. During the 1000s, the Normans developed these into Motte and Bailey castle designs. Effectively, a ‘Motte’ was a large mound of earth, and a ‘Bailey’ was the flattened area beside the mound. The ‘Motte’ could be surrounded with a ditch, and buildings could be placed on the bailey – made of timber or, if time permitted, stone. The key benefit of Motte & Bailey castles was that they were very quick to build, but pretty difficult to attack. -

REGISTER of MEMBERS' INTERESTS NOTICE of REGISTRABLE INTERESTS Councillor Wendy Agnew Ward 18

REGISTER OF MEMBERS’ INTERESTS NOTICE OF REGISTRABLE INTERESTS Councillor Wendy Agnew Ward 18 – Stonehaven and Lower Deeside 1. Remuneration 2. Related Undertakings N/A 3. Contracts with the Authority N/A 4. Election Expenses None 5. Houses, Land and Buildings Residence – land and building at Upper Craighill, Arbuthnot, Laurencekirk, AB30 1LS, owner and occupier 6. Interest in Shares and Securities N/A 7. Non-Financial Interests Manager of Agnew Insurance Appointed trustee of Stonehaven Recreation Ground (deleted 05/09/14) 8. Gifts and Hospitality None REGISTER OF MEMBERS’ INTERESTS NOTICE OF REGISTRABLE INTERESTS Councillor David Aitchison Ward 13 – Westhill and District 1. Remuneration Employee of Valuation Office Agency. I hold the post of Valuation Executive. 2. Related Undertakings None 3. Contracts with the Authority None 4. Election Expenses Election expenses of £272 paid by the Scottish National Party 5. Houses, Land and Buildings Joint Owner (mortgaged) of 2 Fare Park Circle, Westhill, Aberdeenshire, AB32 6WJ 6. Interest in Shares and Securities None 7. Non-Financial Interests None 8. Gifts and Hospitality None REGISTER OF MEMBERS’ INTERESTS NOTICE OF REGISTRABLE INTERESTS Councillor Amanda Allan Ward 13 – Westhill and District 1. Remuneration Costco Wholesale, Endeavour Drive, Westhill, AB32 6UF - Service Clerk 2. Related Undertakings None 3. Contracts with the Authority None 4. Election Expenses £60 from SNP Council Group 5. Houses, Land and Buildings Shared ownership of Waulkmill Croft, Sauchen, Inverurie, AB51 7QR (no interest as of January 2015 - deleted 15/05/15) 6. Interest in Shares and Securities None 7. Non-Financial Interests Appointed as Garioch Area Committee representative on Garioch and North Marr Community Safety Group in 2012 (added 15/05/15) 8. -

Pictish Symbol Stones and Early Cross-Slabs from Orkney

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 144 (2014), PICTISH169–204 SYMBOL STONES AND EARLY CROSS-SLABS FROM ORKNEY | 169 Pictish symbol stones and early cross-slabs from Orkney Ian G Scott* and Anna Ritchie† ABSTRACT Orkney shared in the flowering of interest in stone carving that took place throughout Scotland from the 7th century AD onwards. The corpus illustrated here includes seven accomplished Pictish symbol- bearing stones, four small stones incised with rough versions of symbols, at least one relief-ornamented Pictish cross-slab, thirteen cross-slabs (including recumbent slabs), two portable cross-slabs and two pieces of church furniture in the form of an altar frontal and a portable altar slab. The art-historical context for this stone carving shows close links both with Shetland to the north and Caithness to the south, as well as more distant links with Iona and with the Pictish mainland south of the Moray Firth. The context and function of the stones are discussed and a case is made for the existence of an early monastery on the island of Flotta. While much has been written about the Picts only superb building stone but also ideal stone for and early Christianity in Orkney, illustration of carving, and is easily accessible on the foreshore the carved stones has mostly taken the form of and by quarrying. It fractures naturally into flat photographs and there is a clear need for a corpus rectilinear slabs, which are relatively soft and can of drawings of the stones in related scales in easily be incised, pecked or carved in relief. -

Shell Keeps-Catalogue1

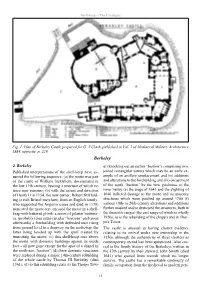

Shell-keeps - The Catalogue Fig. 1. Plan of Berkeley Castle prepared for G. T Clark, published in Vol. 1 of Mediaeval Military Architecture, 1884, opposite. p. 229. Berkeley 2. Berkeley er (knocking out an earlier “bastion”) comprising two, Published interpretations of the shell-keep have as- joined rectangular towers which may be an early ex- sumed the following sequence: (a) the motte was part ample of an artillery emplacement and (ii) additions of the castle of William fitzOsbern, documented in and alterations to the forebuilding and (iii) encasement the late 11th century, bearing a structure of which no of the south “bastion” by the new gatehouse to the trace now remains; (b) with the assent and direction inner bailey (e) the siege of 1645 and the slighting of of Henry II in 1154, the new owner, Robert fitzHard- 1646 inflicted damage to the motte and its masonry ing (a rich Bristol merchant, from an English family, structures which were patched up around 1700 (f) who supported the Angevin cause and died in 1170) various 18th- to 20th-century alterations and additions truncated the motte-top, encased the motte in a shell- further masked and/or destroyed the structures, both in keep with battered plinth, a series of pilaster buttress- the domestic ranges (the east range of which is wholly es, (probably) four semi-circular “bastions” and (soon 1920s, as is the rebuilding of the chapel) and in Thor- afterwards) a forebuilding with defended stair rising pe's Tower. from ground level to a doorway on the motte-top, the The castle is unusual in having charter evidence latter being leveled up with the spoil created by relating to its revival under new ownership in the truncating the motte; (c) this shell-keep rose above 1150s, although the authenticity of these charters as the motte, with domestic buildings against its inside contemporary record has been questioned. -

THE VIKINGS in ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell

THE VIKINGS IN ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell Introduction In recent years, it has been suggested that the first permanent Scandinavian presence in Orkney was not the result of forcible land-taking by Vikings, but came about instead through gradual penetration - a period which has been described as one of'informal' settlement (Morris 1985: 213; 1998: 83). Such would have involved a phase of co-existence, or even integration, between the native Picts and the earliest Norse settlers. This initial period, it is supposed, was then followed by 'a second, formal, settlement associated with the estab lishment of an earldom' (Morris 1998: 83 ), in the late 9'h century. The archaeological evidence advanced in support of the first 'period of overlap' is, however, open to alternative interpretation and, indeed, Alfred Smyth has com mented ( 1984: 145), in relation to the annalistic records of the earliest Viking attacks on Ireland, that these 'strongly suggest that the Norwegians did not gradually infiltrate the Northern Isles as farmers and fisherman and then sud denly tum nasty against their neighbours'. Others have supposed that the first phase of Norse settlement in Orkney would have involved, in the words of Buteux (1997: 263): 'ness-taking' (the fortifying of a headland by means of a cross-dyke) and the occupation of small off-shore islands. Crawford ( 1987: 46) argues that headland dykes on Orkney can be interpreted as indicating ness-taking. However many are equally likely to be prehistoric land boundaries, and no bases on either headlands or small islands have yet been positively identified. Buteux continues his discussion by observing, most pertinently, that: While this can not be taken as suggesting that such sites do not remain to be uncovered, the striking fact is that almost all identified Viking-period settlements in the Northern Isles are found overlying or immediately adjacent to sites which were occupied in the preceding Pictish period and which, furthermore, had frequently been settlements of some size and importance. -

How the Elizabethans Explained Their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia Christopher Ludden McDaid College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McDaid, Christopher Ludden, "Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625918. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4bnb-dq93 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained Their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fufillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Christopher Ludden McDaid 1994 Approval Sheet This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts r Lucfclen MoEfaid Approved, October 1994 _______________________ ixJLt James Axtell John Sel James Whittenourg ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................................. -

CSG Bibliog 24

CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 29 (2016) By Dr Gillian Scott with the assistance of Dr John R. Kenyon Introduction Hello and welcome to the latest edition of the CSG annual bibliography, this year containing over 150 references to keep us all busy. I must apologise for the delay in getting the bibliography to members. This volume covers publications up to mid- August of this year and is for the most part written as if to be published last year. Next year’s bibliography (No.30 2017) is already up and running. I seem to have come across several papers this year that could be viewed as on the periphery of our area of interest. For example the papers in the latest Ulster Journal of Archaeology on the forts of the Nine Years War, the various papers in the special edition of Architectural Heritage and Eric Johnson’s paper on moated sites in Medieval Archaeology. I have listed most of these even if inclusion stretches the definition of ‘Castle’ somewhat. It’s a hard thing to define anyway and I’m sure most of you will be interested in these papers. I apologise if you find my decisions regarding inclusion and non-inclusion a bit haphazard, particularly when it comes to the 17th century and so-called ‘Palace’ and ‘Fort’ sites. If these are your particular area of interest you might think that I have missed some items. If so, do let me know. In a similar vein I was contacted this year by Bruce Coplestone-Crow regarding several of his papers over the last few years that haven’t been included in the bibliography. -

The River Tay - Its Silvery Waters Forever Linked to the Picts and Scots of Clan Macnaughton

THE RIVER TAY - ITS SILVERY WATERS FOREVER LINKED TO THE PICTS AND SCOTS OF CLAN MACNAUGHTON By James Macnaughton On a fine spring day back in the 1980’s three figures trudged steadily up the long climb from Glen Lochy towards their goal, the majestic peak of Ben Lui (3,708 ft.) The final arête, still deep in snow, became much more interesting as it narrowed with an overhanging cornice. Far below to the West could be seen the former Clan Macnaughton lands of Glen Fyne and Glen Shira and the two big Lochs - Fyne and Awe, the sites of Fraoch Eilean and Dunderave Castle. Pointing this out, James the father commented to his teenage sons Patrick and James, that maybe as they got older the history of the Clan would interest them as much as it did him. He told them that the land to the West was called Dalriada in ancient times, the Kingdom settled by the Scots from Ireland around 500AD, and that stretching to the East, beyond the impressively precipitous Eastern corrie of Ben Lui, was Breadalbane - or upland of Alba - part of the home of the Picts, four of whose Kings had been called Nechtan, and thus were our ancestors as Sons of Nechtan (Macnaughton). Although admiring the spectacular views, the lads were much more keen to reach the summit cairn and to stop for a sandwich and some hot coffee. Keeping his thoughts to himself to avoid boring the youngsters, and smiling as they yelled “Fraoch Eilean”! while hurtling down the scree slopes (at least they remembered something of the Clan history!), Macnaughton senior gazed down to the source of the mighty River Tay, Scotland’s biggest river, and, as he descended the mountain at a more measured pace than his sons, his thoughts turned to a consideration of the massive influence this ancient river must have had on all those who travelled along it or lived beside it over the millennia. -

31St May 2020. 18—20 See Page 2 CST Grants 20—22 Above , Carrigreececkfergus Tour Castle 201423 ©T.Welstead Above, Carrickfergus 1 Castle 2014 T

THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP BULLETIN VOLUME 30 AUTUMN 2019 Inside this issue Editorial Editorial As I look up, a little bleary-eyed from my PhD, I realise yet another 1 summer and autumn has flown past at what seems a very rapid rate. Diary dates However fast it went, there have been many archaeological digs and 1 research projects at castle sites of both great and small scale, such as at Bamburgh (Northumberland), Pendragon (Cumbria) and Shrewsbury CSG Conference date change (Shropshire). In addition, the restoration and conservation of sites has 2 also been undertaken such as the completion of restoration works at Pontefract Castle and the reroofing of Carrickfergus Castle. A selection of Obituaries which are included in this newsletter. 2—3 Leeds IMC Please take note about the change of date of the April 4—6 conference. Sentencing Guidelines 7—9 Thank you to those who have suggested and submitted pieces for this bulletin. Excavation at Pendragon Castle 9—10 Therron Welstead CSG Bulletin Editor Moving Image Archive 10 …………………………………… Fortress Scotland 11—14 Scottish Castles for Diary Dates Sale 15—17 CSG 2020 conference ‘Castles of Ayrshire’ English Heritage Projects 28th -31st May 2020. 18—20 See page 2 CST grants 20—22 Above , CarriGreececkfergus Tour Castle 201423 ©T.Welstead Above, Carrickfergus 1 Castle 2014 T. Welstead Castle Studies Group Bulletin Autumn 2019 CSG Conference Change of Diary Date CSG 34th Annual Conference, Irvine, Ayrshire: 28-31 May, 2020 Better late than never! An unexpected setback, which delayed preparations for this event and even at one stage seriously threatened its viability, has finally been resolved, and we are pleased to confirm that the conference will take place in the original venue, the Riverside Lodge Hotel, 46 Annick Road, Irvine, KA11 4LD, but it will be held just over a month later than planned, that is, from the evening of Thursday 28 May through to Sunday, 31 May, 2020. -

Sweetheart Abbey and Precinct Walls Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC216 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90293) Taken into State care: 1927 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2013 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SWEETHEART ABBEY AND PRECINCT WALLS We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH SWEETHEART ABBEY SYNOPSIS Sweetheart Abbey is situated in the village of New Abbey, on the A710 6 miles south of Dumfries. The Cistercian abbey was the last to be set up in Scotland. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Scotland's Geodiversity, Provides a Source of Basic Raw Materials: Raw Basic of Source a Provides Geodiversity, Scotland's

ROCKS,FOSSILS, LANDFORMS AND SOILS AND LANDFORMS ROCKS,FOSSILS, Cover photograph:Glaciatedmountains,CoireArdair,CreagMeagaidh. understanding. e it and promote its wider its promote and it e conserv to taken being steps the and it upon pressures the heritage, Earth Scotland's of diversity the illustrates leaflet This form the foundation upon which plants, animals and people live and interact. interact. and live people and animals plants, which upon foundation the form he Earth. They also They Earth. he t of understanding our in part important an played have soils and landforms fossils, rocks, Scotland's surface. land the alter the landscapes and scenery we value today, how different life-forms have evolved and how rivers, floods and sea-level changes a changes sea-level and floods rivers, how and evolved have life-forms different how today, value we scenery and landscapes the re continuing to continuing re CC5k0309 mates have shaped have mates cli changing and glaciers powerful volcanoes, ancient continents, colliding how of story wonderful a illustrates It importance. Printed on environmentally friendly paper friendly environmentally on Printed nternational i and national of asset heritage Earth an forms and istence, ex Earth's the of years billion 3 some spanning history, geological For a small country, Scotland has a remarkable diversity of rocks, fossils, landforms and soils. This 'geodiversity' is the res the is 'geodiversity' This soils. and landforms fossils, rocks, of diversity remarkable a has Scotland country, small a For ult of a rich and varied and rich a of ult Leachkin Road, Inverness, IV3 8NW. Tel: 01463 725000 01463 Tel: 8NW.