TWAS Newsletter Vol. 14 No. 4 (Oct-Dec 2002)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICT4SD Final Draft-P

Information and Communications Technology for Sustainable Development Defining a Global Research Agenda A Report based on two workshops organized by: Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore Washington, DC, 2003, and Bangalore, 2004 Authors Rahul Tongia, Carnegie Mellon University Eswaran Subrahmanian, Carnegie Mellon University V. S. Arunachalam, Carnegie Mellon University / Tamil Nadu State Planning Commission Information and Communications Technology for Sustainable Development Defining a Global Research Agenda ICT-SD Project Investigators: USA (Supported by National Science Foundation, World Bank, and the United Nations) V. S. Arunachalam, Carnegie Mellon University Raj Reddy, Carnegie Mellon University Rahul Tongia, Carnegie Mellon University Eswaran Subrahmanian, Carnegie Mellon University India (Supported by Govt. of India through its Ministries, Departments and Agencies) N. Balakrishnan, Indian Institute of Science © 2005 Rahul Tongia, Eswaran Subrahmanian, V. S. Arunachalam ISBN : 81 - 7764 - 839 - X Allied Publishers Pvt. Ltd. Jayadeva Hostel Building, 5th Main Road, Gandhi Nagar, Bangalore - 560 009, India. “We must look ahead at today's radical changes in technology, not just as forecasters but as actors charged with designing and bringing about a sustainable and acceptable world. New knowledge gives us power for change: for good or ill, for knowledge is neutral. The problems we face go well beyond technology: problems of living in harmony with nature, and most important, living in harmony with each other. Information technology, so closely tied to the properties of the human mind, can give us, if we ask the right questions, the special insights we need to advance these goals.” Herbert Simon , 1916 – 2001 Nobel Laureate in Economics, 1978 7 Preface Technology remains as the fountainhead for human development and economic growth. -

Banaras Law Journal 2012 Vol 41 No.1

THE BANARAS LAW JOURNAL Cite This Issue as Vol. 41 No.1 Ban.L.J. (2012) Editor Executive Editor Prof. D.P. Verma Dr. M.N. Haque BANARAS LAW JOURNAL PUBLICATION COMMITTEE Prof. D. P. Verma - Head & Dean Dr. M. N. Haque - Executive Editor Dr. Sibaram Tripathy Dr. Ajendra Srivastava Dr. V. K. Pathak Dr. V. P. Singh The Banaras Law Journal is published bi-annually by the Faculty of Law, Banaras Hindu University since 1965.Articles and other contributions for possible publication are welcomed and these as well as books for review should be addressed to the Editor, Banaras Law Journal, Faculty of Law, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi - 221005, India. Views expressed in the Articles, Notes & Comments, Book Reviews and all other contributions published in this Journal are those of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Editors of the Banaras Law Journal. In spite of our best care and caution, errors and omissions may creep in, for which our patrons will please bear with us and any discrepancy noticed may kindly be brought to our knowlede which will improve our Journal. Further it is to be noted that the Journal is published with the understanding that Authors, Editors, Printers and Publishers are not responsible for any damages or loss accruing to any body. In exchange for Banaras Law Journal, the Law School, Banaras Hindu University would appreciate receiving Journals, Books and monographs, etc. which can be of interest to Indian specialists and readers. c Law School, B.H.U., Varanasi-05 Composed and Printed by Raj Kumar Jaiswal, Dee Gee Printers, Khojwan Bazar, Varanasi-221010, U.P., (India). -

Appendix 4: Bangalore Workshop Details

106 ICT for Sustainable Development: Defining a Global Research Agenda Appendix 4: Bangalore Workshop Details Agenda – Bangalore Workshop on IT and Sustainable Development January 14-16, 2004 January 14, 2004 (Day 1) 10:00-10:30 am: Registration and Tea Welcome Remarks – Prof. N. Balakrishnan, IISc. Plenary 10:30-10:45 am: Session Opening Remarks – Ms. JoAnne DiSano, UN; Dr. Carlos Braga, World Bank; and Dr. Peter Freeman, NSF 10:45-11:00 am: ICT for SD: A resume – Prof. V. S. Arunachalam, CMU Chair: (1) Dr. A. Ramachandran Keynote Address on WSIS and ICT: (UN, retd.) 11:00-12:20 am: (1) Mr. Nitin Desai, UN (retd.) (2) Mr. K.K. (2) Prof. Richard Newton, UC-Berkeley Jaswal (MCIT, India) Developing Country Needs and Perspectives in ICT – Prof. 12:20-12:35 pm: Susana Finquelievich, University of Buenos Aires 12:35-2:00 pm: Lunch 2:00-5:30 pm: Working Groups 7:30-9:30 pm: Dinner January 15, 2005 (Day 2) Plan of Action/Announcements Chair: Keynote Address on Development and Economics Dr. Carlos Braga 9:30-10:10 am: Prof. Joseph Stiglitz, Columbia University (World Bank) 10:10-12:30 pm: Working Groups 12:30-1:30 pm: Lunch Development and Security – Dr. Ronald Lehman, Lawrence 1:30-2:00 pm: Livermore Natl. Lab ICT & Development: Who Pays, How Much? – Prof. Raj Reddy, 2:00-2:15 pm: CMU Chair: Ms. JoAnne DiSano (UN) Co-Chairs: Dr. S. 2:15-5:15 pm: Presentations by Working Groups and Joint Discussions Varadarajan (INSA), Prof. Bill Scherlis (CMU) 7:30-9:30 pm: Dinner Appendices 107 January 16, 2004 (Day 3) Remarks by – (Late) Dr. -

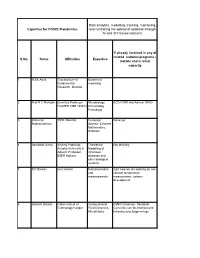

Data Analytics and Modeling

Data analytics, modelling, tracking, monitoring, Expertise for COVID /Pandemics and controlling the spread of outbreak through AI and IOT-based solutions If already involved in any of related national programs : S.No. Name Affiliation Expertise Details and in what capacity 1 H. M. Antia Tata Institute of Numerical Fundamental modelling Research, Mumbai 2 Prof R C Mahajan Emeritus Professor Microbiology ECD ICMR and Advisor WHO PGIMER CHD 160012 Immunology Parasitogy 3 Jaikumar TIFR, Mumbai Computer None yet. Radhakrishnan Science, Discrete Mathematics, Software 4 Somdatta Sinha Visiting Professor, Theoretical Not officially. Ashoka University & Modelling of Adjunct Professor, infectious IISER Kolkata diseases and other biological systems 5 S K Biswas iiser mohali Instrumentation right now we are working on non and contact temperature measurements measurement system development 6 Gautam Biswas Indian Intitute of Computational GIAN (Chairman, Sectional Technology Kanpur Fluid Dynamics, Committee on Mechanical and Microfluidics Infrastructure Engineering) 7 Ram Ramaswamy IIT Delhi Modeling - 8 Sandip Paul Ramanujan Fellow NGS data NA analysis, adaptive evolution 9 Amish kumar Ph.D. Student Bioinformatics After submission of my Ph.D thesis I am working as visitor research student at Department of plant sciences under Project entitled as "TIGR2ESS: Transforming India's Green Revolution by Research and Empowerment for Sustainable food Supplies". 10 Surajit Assistant Professor, Immunology, None Bhattacharjee Department of Infection Biology Molecular -

Year Book of the Indian National Science Academy

AL SCIEN ON C TI E Y A A N C A N D A E I M D Y N E I A R Year Book B of O The Indian National O Science Academy K 2019 2019 Volume I Angkor, Mob: 9910161199 Angkor, Fellows 2019 i The Year Book 2019 Volume–I S NAL CIEN IO CE T A A C N A N D A E I M D Y N I INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY New Delhi ii The Year Book 2019 © INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY ISSN 0073-6619 E-mail : esoffi [email protected], [email protected] Fax : +91-11-23231095, 23235648 EPABX : +91-11-23221931-23221950 (20 lines) Website : www.insaindia.res.in; www.insa.nic.in (for INSA Journals online) INSA Fellows App: Downloadable from Google Play store Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) Professor Gadadhar Misra, FNA Production Dr VK Arora Shruti Sethi Published by Professor Gadadhar Misra, Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) on behalf of Indian National Science Academy, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi 110002 and printed at Angkor Publishers (P) Ltd., B-66, Sector 6, NOIDA-201301; Tel: 0120-4112238 (O); 9910161199, 9871456571 (M) Fellows 2019 iii CONTENTS Volume–I Page INTRODUCTION ....... v OBJECTIVES ....... vi CALENDAR ....... vii COUNCIL ....... ix PAST PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xi RECENT PAST VICE-PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xii SECRETARIAT ....... xiv THE FELLOWSHIP Fellows – 2019 ....... 1 Foreign Fellows – 2019 ....... 154 Pravasi Fellows – 2019 ....... 172 Fellows Elected (effective 1.1.2019) ....... 173 Foreign Fellows Elected (effective 1.1.2019) ....... 177 Fellowship – Sectional Committeewise ....... 178 Local Chapters and Conveners ...... -

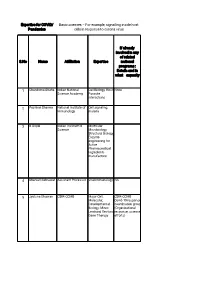

Basic Sciences – for Example, Signalling Inside Host Pandemics Cells in Response to Corona Virus

Expertise for COVID/ Basic sciences – For example, signalling inside host Pandemics cells in response to corona virus If already involved in any of related S.No Name Affiliation Expertise national programs : Details and in what capacity 1 Chandrima Shaha Indian National Cell Biology, Host None Science Academy Parasite interactions 2 Pushkar Sharma National Institute of Cell signaling, Immunology malaria 3 B Gopal Indian Institute of Molecular Science Microbiology, Structural Biology, Enzyme engineering for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients manufacture 4 Sharvan Sehrawat Assistant Professor Viral immunology NA 5 Jyotsna Dhawan CSIR-CCMB Major-Cell, CSIR-CCMB Molecular, Covid-19 response Developmental coordination group Biology; Minor: (Organizational Lentiviral Vectors, response, science Gene Therapy efforts) 6 G. Baskaran The Institute of Theoretical Mathematical Physics. Sciences, Chennai Curious about 600 113 and biological IITMadras processes for decades. 7 Pradip Kumar Jamia Hamdard, NewMolecular NA Chakraborti Delhi 110062 Microbiology, Infectious disease, prokaryotic signalling 8 Nahid Ali CSIR Indian institute Parasitology, of chemical biology immunology 9 Raj Kumar Roy IISER Mohali Polymer and No Material Chemistry 10 Narinder K. Mehra All India Institute of COVID-19 and Medical Sciences immunity, Laboratory diagnosis 11 V. Ramanathan IIT(BHU) Varanasi Raman imaging Have been helping for disease the administrative diagnosis authorities of my city and my institute in making and distributing hand sanitizers. Till date have made around -

September 05, 2014

Report of the Activities Organized by Silizium‐Electronics Society Department of Electronics, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya College March 2014‐March 2015 September 05, 2014 The Inaugural Function for Electronics Society “Silizium” was held on 05‐Sep‐2014 in Seminar Hall. The Programme started at 10.00am with a Welcome Address by Ankita Chugh, a student of B.Tech Electronics Sem III followed by Lamp Lighting. Dr Poonam Kasturi, Convener for the Inaugural Function formally introduced Dr. Anand Kumar Sethi to the gathering. Dr. Anand Kumar Sethi unveiled the Society Name, Logo and Tagline. It was followed by an enlightening talk by Dr. Sethi on “Electronics in India : Past, Present & Future”. After the talk the final round for Technical Presentation started in Electronics Lab in New Building at 11.30 am. This Technical Presentation was judged by Dr. Ravinder Kaur. The idea for the two competitions was proposed in the Weekly Department Faculty Meeting on 04‐Aug‐2014 i.e. Monday. The announcement for the same was done officially to the students on 07‐Sep‐2014 i.e. Wednesday. Students were active towards the event & 6 entries were received for the Society Name Logo & Tagline. The details for the same are as follows : Student Year Name Logo Tag line Namrata 3rd Silicium The Innovative Society Koli year Ujjawal 3rd Tech Labs Wants to be Techlabist Mahajan Year Himanshu 3rd Vidyut ‐‐‐ year Rahul Soni 3rd Currentronix‐ ‐‐‐ ‐‐‐ year Volta Shivam 1st ‐‐‐ ‐‐‐ Sharma year 3rd Dexterous Neha Year Society INNOVATION IS DOING NEW THING AND Minhas YES We CaN dO eVeRyThInG pOsSiBlE Page 1 of 26 Report of the Activities Organized by Silizium‐Electronics Society Department of Electronics, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya College March 2014‐March 2015 After several rounds of discussion among the Faculty Members the name “Silicium” proposed by Namrata Koli was chosen with a little modification to the final name “Silizium”. -

Incorporation of 3H-Thymidine in Human

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Publications of the IAS Fellows J. MED. MICROBI0L.-VOL. 14 (1981), 279-293 0022-26 15/8 1/M07 0279 $02.00 0 1981 The Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland INCORPORATION OF 3H-THYMIDINE IN MYCOBACTERIUM LEPRAE WITHIN DIFFERENTIATED HUMAN MACROPHAGES H. K. PRASADAND INDIRANATH Department of Pathology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi-110029, India PLATEXV SUMMARY.The factors influencing the incorporation of 3H-thymidine (3H-Tdr) in the DNA of Mycobacterium leprae within macrophages derived from human blood have been evaluated. Fifty strains of M. leprae derived from skin nodules of patients with lepromatous leprosy were studied for their ability to incorporate 3H-Tdr. Control macro- phages of the same donor maintained alone, or with autoclaved M. leprae, showed low levels of baseline 3H-Tdr incorporation. During a 15-day period of pulsing, 27 of the M. leprae strains incorporated 3H-Tdr at levels of 2 162834% of the incorporation by control cultures. Significant incorporation was observable by the second week of culture and cumulative increases occurred by the third week. A 24-h pulse with 3H-Tdr was inadequate for a detectable increase. A minimal duration of 4-5 days of continuous pulsing was required to obtain a significant increase in the incorporation of 3H-Tdr. Of the 50 M. leprae strains, 23 (46%) failed to incorporate the radiolabel. This failure was apparently not related to differences in the disease status of patients, to the transport conditions for the biopsies, to morphological indices of the extracted M. -

The Year Book 2019

THE YEAR BOOK 2019 INDIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Bengaluru Postal Address: Indian Academy of Sciences Post Box No. 8005 C.V. Raman Avenue Sadashivanagar Post, Raman Research Institute Campus Bengaluru 560 080 India Telephone : +91-80-2266 1200, +91-80-2266 1203 Fax : +91-80-2361 6094 Email : [email protected], [email protected] Website : www.ias.ac.in © 2019 Indian Academy of Sciences Information in this Year Book is updated up to 22 February 2019. Editorial & Production Team: Nalini, B.R. Thirumalai, N. Vanitha, M. Venugopal, M.S. Published by: Executive Secretary, Indian Academy of Sciences Text formatted by WINTECS Typesetters, Bengaluru (Ph. +91-80-2332 7311) Printed by Lotus Printers Pvt. Ltd., Bengaluru CONTENTS Page Section A: Indian Academy of Sciences Memorandum of Association ................................................... 2 Role of the Academy ............................................................... 4 Statutes .................................................................................. 7 Council for the period 2019–2021 ............................................ 18 Office Bearers ......................................................................... 19 Former Presidents ................................................................... 20 Activities – a profile ................................................................. 21 Academy Document on Scientific Values ................................. 25 The Academy Trust ................................................................. 33 Section B: Professorships -

Indira Nath, Talked to Nature Medicine About the Changes She Has Seen in Her Work Environment During Her Long Career

NEWS India’s leading female scientist, Indira Nath, talked to Nature Medicine about the changes she has seen in her work environment during her long career. In what might seem surprising for a developing country, she reveals that India’s biomedical research community is both respected by government and also respects its female members. Indira Nath It was 45° Celsius in New Delhi the day I what he could do for them during his largest country for leprosy,” says Nath. talked with Indira Nath by telephone. Too tenure. “We told him about the amount of Nevertheless, she is encouraged that in hot to work. Nearly too hot to think. permission needed for customs clearance her lifetime at least the clinical picture of Unbearable temperatures were the least of and he fixed that within less than a year.” the disease has changed. Earlier detection the problems that Nath faced when she re- Applying for foreign research money and better treatment means that the awful turned to her native India to pursue a ca- was, and still is, even harder. “Grant appli- disfigurements that were commonplace reer in research in the early 1970s. Meager cations had first to be sent for local scien- are now rare. resources—both material and financial— tific peer review and receive government By the mid-1980s, Nath wanted to intro- and incalculable layers of bureaucracy clearance by political and economic bodies duce more of a molecular slant to her work, plagued scientific investigation. But two et cetera. It used to take years. By the time it a desire that luckily coincided with the things that Nath had in abundance were reached the international government’s drive to in- leprosy patients and the determination to agencies it might not even be crease its biotechnology ca- make a homespun contribution to leprosy relevant.” pabilities. -

Us-India Strategic Dialogue on Biosecurity

US-INDIA STRATEGIC DIALOGUE ON BIOSECURITY REPORT FROM THE FIRST DIALOGUE SESSION WASHINGTON, DC, 20-21 SEPTEMBER 2016 UPMC Center for Health Security REPORT RELEASE: OCTOBER 2016 UPMC Center for Health Security Project Team Gigi Kwik Gronvall, PhD Principal Investigator Senior Associate Sanjana Ravi, MPH Senior Analyst Tom Inglesby, MD Chief Executive Officer & Director Anita Cicero, JD Chief Operating Officer and Deputy Director Project Sponsor Project on Advanced Systems and Concepts for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction; supported by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency Institute for National Security Studies, United States Air Force (current) Formerly of the Naval Postgraduate School 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................4 Meeting Overview ..........................................................................................................................6 Priorities, Strengths, and Challenges in National Biosecurity .............................................6 Strengthening National and International Responses to Natural Threats ............................6 Remarks by Rear Admiral Kenneth Bernard .......................................................................7 White House Briefing: Global Health Security & Biodefense ............................................7 -

Indira Nath: I Recall, When I Was About River Yamuna, Somewhere Near Shahdara, Gauhar Raza: at That Time a Lot of Ten, I Wanted to Do Medicine

IN CONVERSATION INTERVIEW very much, but he asked me to come and part of dermatology. Dermatology is a see some leprosy patients. That was his fraction of the regular medicine and so hobby at weekends, he used to go to see you can imagine leprosy sort of gets one Gauhar Raza: Let me begin by asking the leprosy patients. In those days the paragraph in the textbook. you: Why did you choose science? leprosy patients were located all along the Indira Nath: I recall, when I was about river Yamuna, somewhere near Shahdara, Gauhar Raza: At that time a lot of ten, I wanted to do medicine. But when in Delhi, and it was like a colony of lepers. stigma, myths, superstitions were I came into medicine, I realized, pretty They were outcasts. He was part of a associated with leprosy across the world. early on, that even if I live to be hundred, social group. In that social group, there People were scared of even going close to and serve patients, how many people was a lady who used to come and pick me lepers and touching them and you started would I make a difference to? Whereas I up in a red Mercedes. She was the wife of working in a colony full of lepers. Were felt, if I did research that perhaps could the governor of the Reserve Bank of India. you not scared? make a bigger impact. We would go to the colony and did simple Indira Nath: No, I was not scared. That things like bandaging their ulcers, trying part didn’t affect me, the social aspect Gauhar Raza: What inspired you to take to get them magazines.