Pathologies and Dysfunctions of Democracy in the Media Context 2Nd Volume João Carlos Correia Anabela Gradim Ricardo Morais (Eds.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 06/04/2021 10:43:23 AM

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 06/04/2021 10:43:23 AM 06/03/21 Thursday This material is distributed by Ghebi LLC on behalf of Federal State Unitary Enterprise Rossiya Segodnya International Information Agency, and additional information is on file with the Department of Justice, Washington, District of Columbia. Beijing, Hanoi Agree to Establish Naval Hotline to Resolve Emergencies in South China Sea by Morgan Artvukhina While the two nations have a history of sometimes-violent border disputes, China and Vietnam have emphasized the increasing importance of political and economic cooperation since normalizing relations in 1991. Nonetheless, Washington has tried to pry Vietnam and other Southeast Asian nations away from working with China. Chinese and Vietnamese naval leaders have agreed to set up a naval hotline as part of a larger effort to defuse tensions in the South China Sea. This comes after their respective heads of state recently agreed to improve diplomatic and trade relations, too. Rear Admiral Tran Thanh Nghiem, Commander of the Vietnam People’s Navy, held an online talk with Admiral Shen Jinlong, Commander of the People's Liberation Army Navy last week to discuss military relations between the two socialist nations, which are sometimes fraught with dispute and confrontation over competing claims to parts of the South China Sea. According to the Vietnamese defense ministry’s official People’s Army Newspaper, “the two sides agreed to enhance the sharing of information related to situations at sea and issues of mutual concern, study the possibility of setting up a hotline to connect the two navies, and maintain the joint patrol mechanism in the Gulf of Tonkin.” The People’s Army Newspaper further notes that Nghiem hailed previous efforts at improving bilateral defense cooperation and the regular meetings between naval leaders, organization of patrols, and joint drills at sea. -

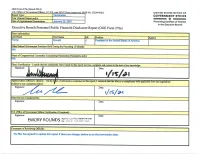

Financial Disclosure Report (OGE Form 278E)

OGE Form 278e (March 2014) U.S. Office of Government Ethics· 5 C.F.R. art 2634 Form A roved: 0MB No. (3209-0001) UNIT£0 STATES O FflCE O F R rt T Tennination GOVERNM ENT ETHICS Date of Appointment/Termination: January 20, 2021 Preventing Confli* cts of lntere,t in the Execu:ive Bran<:h Executive Branch Personnel Public Financial Disclosure Report (OGE Form 278e) Filer's Information •L . Last Name First Name MI Position Agency Trump Donald J President of the United States of America Other Federal Government Positions Held During the Preceding 12 Months: N/A Name of Congressional Committee Considering Nomination (Nominees only): N/A Filer's Certification - I certify that the statements I have made in this report are true, complete and correct to the best of my knowledge: Signature: Date: JJMi •/•'r/- • Agency Ethics Otticial's upwon - Ori the i1.1s of mtormation contained m llllS report, I conclude that the filer 1s in compliance with applicable laws and regulations (subject to any comments be]ow) - Signature: Date: ~ 1/ ,s/ ;;-c Other Review Conducted By: Signature: Date: U.S. Office ofGovernment Ethics Certification (if required): Signature: Date: Comments of Reviewing Officials: The filer has agreed to update this report if there are changes before or on the termination date. OGE Form 278e (March 2014) Instructions for Part 1 Note: This is a public form. Do not include account numbers, street addresses, or family member names. See instructions for required information. Filer's Name Page Number Donald J. Trump 2 of 37 Part 1: Filer's Positions Held Outside United States Government # Organization Name City/State Organization Type Position Held From To 1. -

Emmanuel Macron

MACRON ET TRUMP Jupiter et Mars 3 MACRON ET TRUMP Désiré Kraffa MACRON ET TRUMP Jupiter et Mars 4 « Ma poignée de main avec lui, ce n’est pas l’alpha et l’oméga d’une politique, mais un mo- ment de vérité ». Emmanuel Macron 5 MACRON ET TRUMP Avant-propos En fait rien n'est impossible à condition d'avoir l'entière conviction de pouvoir réalisé l'impossible. Sinon qui aurait cru possible la victoire de Macron et de Trump ? La chance de Macron c’est d’avoir été ministre dans le gouvernement de François Hollande, cela lui a ouvert la porte du champ politique et la crédi- bilité qui va avec. Sans cela il serait dans l’anonymat le plus complet. Les hommes de son envergure, il y a des centaines, voire des milliers en France. Pour Trump, c’est sans nul doute son appartenance à la famille politique républicaine qui était le fil conducteur, car des milliardaires en Amérique il y a des centaines voire des milliers en Amérique, mais pour être politiciens, c’est une autre histoire. Tous deux vont bénéficier des évènements imprévisibles du champ politique pour accomplir leur projet révolutionnaire. Après la victoire de Trump les vents contraires sont en train de soufflé, il ne serait pas le digne représentant des républi- cains. En France c’est le contraire qui s’est 6 produit. Macron n’a pas voulu qu’on l’affilie à la gauche qui l’a vu naitre. Sa stratégie était de dire qu’il n’est pas de gauche, ni même de droite. -

Donald Trump: a Critical Theory-Perspective on Authoritarian Capitalism

tripleC 15(1): 1-72, 2017 http://www.triple-c.at Donald Trump: A Critical Theory-Perspective on Authoritarian Capitalism Christian Fuchs University of Westminster, London, UK, [email protected], @fuchschristian Abstract: This paper analyses economic power, state power and ideological power in the age of Donald Trump with the help of critical theory. It applies the critical theory approaches of thinkers such as Franz Neumann, Theodor W. Adorno and Erich Fromm. It analyses changes of US capitalism that have together with political anxiety and demagoguery brought about the rise of Donald Trump. This article draws attention to the importance of state theory for understanding Trump and the changes of politics that his rule may bring about. It is in this context important to see the complexity of the state, including the dynamic relationship be- tween the state and the economy, the state and citizens, intra-state relations, inter-state rela- tions, semiotic representations of and by the state, and ideology. Trumpism and its potential impacts are theorised along these dimensions. The ideology of Trump (Trumpology) has played an important role not just in his business and brand strategies, but also in his political rise. The (pseudo-)critical mainstream media have helped making Trump and Trumpology by providing platforms for populist spectacles that sell as news and attract audiences. By Trump making news in the media, the media make Trump. An empirical analysis of Trump’s rhetoric and the elimination discourses in his NBC show The Apprentice underpins the analysis of Trumpology. The combination of Trump’s actual power and Trump as spectacle, showman and brand makes his government’s concrete policies fairly unpredictable. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

Case 2:19-cv-01501-MCE-DB Document 10 Filed 08/08/19 Page 1 of 3 1 Bryan K. Weir, CA Bar #310964 Thomas R. McCarthy* 2 William S. Consovoy* 3 Cameron T. Norris* CONSOVOY MCCARTHY PLLC 4 1600 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 700 Arlington, VA 22209 5 (703) 243-9423 6 *Application for admission 7 pro hac vice pending UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 8 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 9 10 11 DONALD J. TRUMP FOR PRESIDENT, No. 19-cv-1501 INC., DONALD J. TRUMP, in his 12 capacity as a private citizen, 13 Plaintiffs, NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION 14 v. 15 ALEX PADILLA, in his official capacity as California Secretary of State, and 16 XAVIER BECERRA, in his official capacity as California Attorney General, 17 Defendants. 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Case 2:19-cv-01501-MCE-DB Document 10 Filed 08/08/19 Page 2 of 3 1 NOTICE 2 Notice is hereby given that Plaintiffs Donald J. Trump for President, Inc. and President 3 Donald J. Trump, in his capacity as a private citizen, make the following motion, which they 4 propose to notice for a hearing on September 5, 2019. 5 MOTION 6 Plaintiffs hereby move for a preliminary injunction enjoining enforcement of the provisions 7 of the Presidential Tax Transparency and Accountability Act, enacted though Senate Bill 27 8 (“SB27”), that require candidates for the presidency to disclose their tax returns as a condition of 9 appearing on a primary ballot. See Cal. Elec. Code §§ 6880-6884. -

2018.10.29 Complaint (Final) Compared With

Case 1:18-cv-09936-LGS Document 78-1 Filed 01/31/19 Page 1 of 204 EXHIBIT A Case 1:18-cv-09936-LGS Document 78-1 Filed 01/31/19 Page 2 of 204 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK JANE DOE, LUKE LOE, RICHARD ROE, and MARY MOE, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Plaintiffs, v. No. _______________________1:18- THE TRUMP CORPORATION, DONALD J. cv-09936-LGS TRUMP, in his personal capacity, DONALD TRUMP JR., ERIC TRUMP, and IVANKA TRUMP, JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Defendants. AMENDED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Case 1:18-cv-09936-LGS Document 78-1 Filed 01/31/19 Page 3 of 204 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 PARTIES .................................................................................................................................. 1112 A. Plaintiffs ............................................................................................................ 1112 B. Defendants ........................................................................................................ 1113 JURISDICTION AND VENUE ............................................................................................... 1214 FACTS ...................................................................................................................................... 1315 I. THE TRUMP ENTERPRISE ....................................................................................... 1315 A. The Trump -

At the End of Division a (Before the Short Title), In- Sert the Following

G:\M\16\COHEN\COHEN_111.XML AMENDMENT TO DIVISION A OF RULES COMMITTEE PRINT 116–59 OFFERED BY MR. COHEN OF TENNESSEE At the end of division A (before the short title), in- sert the following: 1 SEC. ll. (a) None of the funds appropriated or 2 otherwise made available by this Act may be made avail- 3 able to enter into any new contract, grant, or cooperative 4 agreement with any entity listed in subsection (b). 5 (b) The entities listed in this subsection are the fol- 6 lowing: Trump International Trump International Trump International Hotel & Tower Chi- Hotel & Golf Links Hotel Las Vegas, Las cago, Chicago, IL Ireland (formerly The Vegas, NV Lodge at Doonbeg), Doonbeg, Ireland Trump National Doral Trump International Trump SoHo New York, Miami, Miami, FL Hotel & Tower New New York City, NY York, New York City, NY Trump International Trump International Trump International Hotel & Tower, Van- Hotel Waikiki, Hono- Hotel Washington, DC couver, Vancouver, lulu, HI Canada Trump Tower, 721 Fifth Trump World Tower, Trump Park Avenue, Avenue, New York 845 United Nations 502 Park Avenue, City, New York Plaza, New York City, New York City, New New York York Trump International Trump Parc East, 100 Trump Palace, 200 East Hotel & Tower, NY Central Park South, 69th Street, New York New York City, New City, New York York Heritage, Trump Place, Trump Place, 220 River- Trump Place, 200 River- 240 Riverside Blvd, side Blvd, New York side Blvd, New York New York City, New City, New York City, New York York Trump Grande, Sunny Trump Hollywood Flor- Trump -

Donald Trump

Donald Trump For other uses, see Donald Trump (disambiguation). two years, before transferring to the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, because Wharton then had one of the few real estate studies departments in US Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an Ameri- [24] can real estate magnate, television personality, politician, academia. He graduated in 1968, with a Bachelor of Science degree in economics.[25] and author. He is the chairman and president of The Trump Organization and the founder of Trump Enter- Trump came of age for the draft during the Vietnam War. tainment Resorts.[1] Trump’s branding efforts, business In an interview in 2011 on New York station WNYW,[26] career, outspoken manner, media appearances, and books he stated, “I actually got lucky because I had a very high have made him a celebrity. He hosted The Apprentice,[2] draft number.”[27] Selective Service records retrieved by a U.S. television program on NBC. The Smoking Gun from NARA records show that, al- Trump is a son of Fred Trump, a New York City real though Trump did eventually receive a high selective ser- estate developer.[10] Donald Trump worked for his fa- vice lottery number, he was not drafted earlier because of ther’s firm, Elizabeth Trump & Son, while attending the his student deferments (2-S) while attending college, and after receiving a medical deferment (1-Y, later converted Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and, [28] in 1968, officially joined the company.[11] He was given to 4-F) prior to the lottery being initiated. -

L(B )(6) Not the Department of Homeland Security Is Surveing, Monitoring, Or 2/16/2016 Iot Herwise Targeting You Your Request Seeking Records Pertaining To: 1

OHS FOIA Privacy Office Logs - FY 2016 Received between 02/0112016 and 02/29/2016 Requester Request ID Request Description Received Date Name records pertaining to Ope nSource Intelligence, Research and Surveillance 2016·HQF0·00106 (b)(6) I Projects I have not consented to 2/3/2016 records pertaining to the following: 1. All Department of Homeland Security (OHS ) records co ntaining information regard ing Wickr Inc., generated between January 1, 2010 and November 20, 201 5. You De Trani. 2016-HQF0-00114 specifically request that the OHS sea rch its emails and electronic files for 2/4/2016 J ennifer this information. You further specifically req uest all materials regarding any open, ongoing, and/or closed investigations co nducted by OHS focused in whole or in part on Wic kr Inc. any information OH S may have on you 2016-HQF0-00125 (b)(o) 2/10/2016 records pertaining to the following: 1. what investigation was done on her in 2014 and 2014 in order to approve her visa? 2. What identification did she provide? 3. How was her information investigated? 4. What questions was she asked by any agency related to her Visa approval? 5. Pl ease provide any and all documents related to the investigation and approval of J ensen , 2016-HQF0-00142 Tashfeen Malik? 6. What questions are asked of Syrian refugees? 7. how 2/4/2016 JoAnna are any refugees, or people requesting visas of any kind investigated? 8. who pays for refugees or asylum seekers to: a. come to America b. stay in America c. -

Trump 12 Of�8 ,[ Part 1: Filer's Positions Held Outside United States Government T; • Ornuizationname City/State Orcaniutioa Type Position Held from Ji To

:I OGE Fonn 278e (March 2014) I .-:U;;..:.. ::::.::s·...::· O:;..;:ffi=Ic::.::e...::o;.:;.f..;::G..:::..ov.:...::e;:.:rnm=e=nt:..::E::..::th:::i.::.:cs;z_· :;_;;;,5 C.::..F.:.::.R . �.:..=;.:;_:_.�..=-::==t:.:r..:::..o.:..;:ve:..=d.:....;: O:::..:MB No. 209-000 1) UNITED STATES CI)FFtC£ OF .=;- :;.:; (3 , I GOVERNM;�)J ETHICS Preventitlg c-A. ..........· ., , of Interest in the .,., ••�u1taoil• ·, Branch 2015 JUL 15 PM La: 14 Executive Branch Personnel Public Financial Disclosure Report (OGE Form278e) President of the United States of America Date: Date: li \ 2-\ 2-6lS Date: • Comments of Reviewing Officials: with theFederal Election Campaiign Act 00EF-l71e(Mm:hl0\4) Instructions for Part 1 N ot e: Thlstsapu . bfl 1c form. 0o not!n u cJe d ac:count num be.�1 .streetI resses, dd fa or . m II y rn�mbe rnames. See I nstruer rons or requIred lnf orma •on. Filer'sName Page Number ; : Donald J. Trump 12 of�8 ,[ Part 1: Filer's Positions Held Outside United States Government t; • OrnuizationName City/State Orcaniutioa Type Position Held From ji To 1 4 Shadow Tree Lane LLC NewYork,NY LLC Presidant 09126/12 " To Date 2 4 ShadowTree Lane Member Corp NewYork, NY Corporation President/DirectortChairman 09/26/12 d To Date 3 40 Wall Development Associates LLC NewYor1<, NY LLC Member & President 4/11/95 & 8/11/03 'I To Date 4 40 Wall Street Commercial LLC NewYol1<, NY LLC President 08/27/09 il To Date I 5 40 Wall Street LLC NewYol1<, NY LLC President 04/23/98 !i To Date 6 40 Wall Street Member Coro NewYo11<, NY Coroora�on President/Director 04/29/98 ,I To Date 7 3126 Corporation NewYol1<, NY Corporation President/Director 06/01199 'I To Date 8 401 MezzVenture LLC NewYol1<, NY LLC President 10/01/04 il To Date 9 401 North Wabash Venture LLC New York. -

A the TRUMP ORGANIZATION, TRUMP PAYROLL CORP

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK -against THE TRUMP CORPORATION, d / b / a THE TRUMP ORGANIZATION, TRUMP PAYROLL CORP. d / b / a THE TRUMP ORGANIZATION, ALLEN WEISSELBERG , Defendants. THE GRAND JURY OF THE COUNTY OF NEW YORK by this indictment, accuses the Trump Corporation, d / b / a the Trump Organization, Trump Payroll Corp., d / b / a the Trump Organization, and Allen Weisselberg ofthe crime ofSCHEME TO DEFRAUD INTHE FIRST DEGREE, inviolation ofPenalLaw 190.65( ) (b ), committed as follows: The defendants, in the County of New York and elsewhere, during the period from on or about March 31, 2005 , to on or about June 30, 2021, as set forth below, engaged in a scheme constituting a systematic ongoing course of conduct with intent to defraud more than one person and to obtainpropertyfrommorethan one personby false and fraudulentpretenses, representationsand promises, and so obtained property with a value in excess ofone thousand dollars from oneormore such persons, to wit: the UnitedStates Internal RevenueService, the New York State Department of Taxationand Finance, and the New York City DepartmentofFinance. THE DEFENDANTS 1 . The Trump Organization is a trade name that embraces a number of privately held corporate andpartnership entities whose beneficialowners includeDonaldJ. Trump andtheDonald J. TrumpRevocableTrust dated April7 2014; there are nopublicor institutionalshareholders. One of the entities comprising the Trump Organization is the Trump Corporation. The Trump Corporation has its principal place of business at 725 Fifth Avenue, New York New York , a building known as “ Trump Tower . ” Among other things, the Trump Corporation serves as the employer of a group ofsenior managers of the Trump Organization, includingAllen Weisselberg. -

Donald Trump Employment Assets and Income American Ledger

Donald Trump employment assets and income American Ledger 2015 2015 Description # Foreign Income Type Value Income Low High Low High 1290 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS, A TENANCY-IN-COMMON 121 N rent Over $50M Over $50M $5,000,001 $5,000,001 208Underlying Productions Assets: LLC commercial real estate 161 N salary n/a n/a $14,222 $14,222 Location: New York, NY 4(The SHADOW Apprentice) TREE LANE LLC 1 N condo sales $1,001 $15,000 $1,425,000 $1,425,000 Location:See attached Burbank, schedule CA 4%Underlying partnership Assets: interest bank inaccount Spring Creek Plaza LLC 123 N rent $500,001 $1,000,000 $100,001 $1,000,000 Location: Westchester, NY 4%Underlying partnership Assets: interest commercial in Starrett real City estate LP 122 N rent $5,000,001 $25,000,000 $1,000,001 $5,000,000 Location:See attached Brooklyn, schedule NY 40Underlying Wall Development Assets: residential Associates, real LLC estate 171 N unlisted unlisted $0 $0 Location: Brooklyn, NY 40Value WALL reported STREET reflects COMMERCIAL bank account LLC holding only. Entity's 172 N unlisted unlisted $0 $0 other holdings and assets are reported elsewhere; see 40Value Wall reported Street LLC reflects bank account holding only. Entity's 2 N rent n/a n/a $5,000,001 $5,000,001 otherattached holdings schedule. and assetsPass-thru are entity.reported New elsewhere; York, NY see 401Underlying MEZZ VENTURE Assets: commercial LLC real estate 3 N $1,001 $15,000 $0 $200 Location:attached schedule.New York, Payroll NY company. New York, NY 401Underlying North Wabash Assets: bankVenture