Documentary Modes of Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

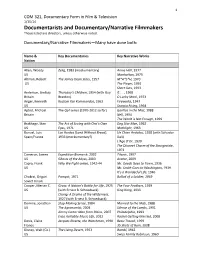

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

Jack C. Ellis and Betsy A. Mclane

p A NEW HISTORY OF DOCUMENTARY FILM Jack c. Ellis and Betsy A. McLane .~ continuum NEW YOR K. L ONDON - Contents Preface ix Chapter 1 Some Ways to Think About Documentary 1 Description 1 Definition 3 Intellectual Contexts 4 Pre-documentary Origins 6 Books on Documentary Theory and General Histories of Documentary 9 Chapter 2 Beginnings: The Americans and Popular Anthropology, 1922-1929 12 The Work of Robert Flaherty 12 The Flaherty Way 22 Offshoots from Flaherty 24 Films of the Period 26 Books 011 the Period 26 Chapter 3 Beginnings: The Soviets and Political btdoctrinatioll, 1922-1929 27 Nonfiction 28 Fict ion 38 Films of the Period 42 Books on the Period 42 Chapter 4 Beginnings: The European Avant-Gardists and Artistic Experimentation, 1922-1929 44 Aesthetic Predispositions 44 Avant-Garde and Documentary 45 Three City Symphonies 48 End of the Avant-Garde 53 Films of the Period 55 Books on the Period 56 v = vi CONTENTS Chapter 5 Institutionalization: Great Britain, 1929- 1939 57 Background and Underpinnings 57 The System 60 The Films 63 Grierson and Flaherty 70 Grierson's Contribution 73 Films of the Period 74 Books on the Period 75 Chapter 6 Institutionalization: United States, /930- 1941 77 Film on the Left 77 The March of Time 78 Government Documentaries 80 Nongovernment Documentaries 92 American and British Differences 97 Denouement 101 An Aside to Conclude 102 Films of the Period 103 Books on the Period 103 Chapter 7 Expansion: Great Britain, 1939- 1945 105 Early Days 106 Indoctrination 109 Social Documentary 113 Records of Battle -

Introducción Al Documental Colección

Introducción al documental COLECCIÓN MIRADAS EN LA OSCURIDAD CENTRO UNIVERSITARIO DE ESTUDIOS CINEMATOGRÁFICOS DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE PUBLICACIONES Y FOMENTO EDITORIAL Bill Nichols Introducción al documental segunda edición UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO MÉXICO, 2013 © Introducción al documental segunda edición del autor © UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO versión en español para todo el mundo CENTRO UNIVERSITARIO DE ESTUDIOS CINEMATOGRÁFICOS Circuito Mario de la Cueva s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, México, 04510, DF Primera edición en español, 2013 Fecha de edición: 30 de octubre, 2013 Introduction to Documentary, second edition, by Bill Nichols Copyright © 2010 by Indiana University Press, Spanish-language translation rights licensed from the English-language Publisher, Indiana University Press Nichols, Bill, autor [Introduction to documentary. Español] Introducción al documental / Bill Nichols; traducción Miguel Bustos García. – Primera edición 368 páginas ISBN: 978-607-02-4799-6 1. Películas documentales--Historia y crítica. I. de: Nichols, Bill. Introduction to documentary. II. Bustos García, Miguel, traductor. III. Título PN1995.9.D6.N49618 2013 Traducción: Miguel Bustos García, para la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México ©, 2013 Edición y diseño de portada: Rodolfo Peláez Fotografía de portada: Maquilapolis (Vicki Funari y Sergio de la Torre, 2006) Cortesía de California Newsreel. D.R.© 2013, UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, México, 04510, DF CENTRO UNIVERSITARIO DE -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 518 IR 000 359 TITLE Film Catalog of The

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 518 IR 000 359 TITLE Film Catalog of the New York State Library. 1973 Supplement. INSTITUTION New York State Education Dept., Albany. Div. of Library Development. PUB DATE 73 NOTE 228p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$11.40 DESCRIPTORS *Catalogs; Community Organizations; *Film Libraries; *Films; *Library Collections; Public Libraries; *State Libraries; State Programs IDENTIFIERS New York State; New York State Division of Library Development; *New York State Library ABSTRACT Several hundred films contained in the New York State Division of Library Development's collection are listed in this reference work. The majority of these have only become available since the issuance of the 1970 edition of the "Catalog," although a few are older. The collection covers a wide spectrum of subjects and is intended for nonschcol use by local community groups; distribution is accomplished through local public libraries. Both alphabetical and subject listings are provided and each"citation includes information about the film's running time, whether it is in color, its source, and its date. Brief annotations are also given which describe the content of the film and the type of audience for which it is appropriate. A directory of sources is appended. (PB) em. I/ I dal 411 114 i MI1 SUPPLEMENT gilL""-iTiF "Ii" Alm k I I II 11111_M11IN mu CO r-i Le, co co FILM CATALOG ca OF THE '1-1-1 NEW YORK STATE LIBRARY 1973 SUPPLEMENT THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT ALBANY, 1973 THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ( with years when terms expire) 1984 JOSEPH W. -

Visual Rhetoric in Environmental Documentaries

VISUAL RHETORIC IN ENVIRONMENTAL DOCUMENTARIES by Claire Ahn BEd The University of Alberta, 2002 MEd The University of British Columbia, 2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Language and Literacy Education) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (VANCOUVER) June 2018 © Claire Ahn, 2018 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: Visual rhetoric in environmental documentaries submitted by Claire Ahn in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Faculty of Education, Department of Language and Literacy Education Examining Committee: Teresa Dobson, Department of Language and Literacy Education Co-supervisor Kedrick James, Department of Language and Literacy Education Co-supervisor Carl Leggo, Department of Language and Literacy Education Supervisory Committee Member Margaret Early, Department of Language and Literacy Education University Examiner Michael Marker, Department of Educational Studies University Examiner ii Abstract Environmental issues are a growing, global concern. UNESCO (1997) notes the significant role media has in appealing to audiences to act in sustainable ways. Cox (2013) specifically remarks upon the powerful role images play in how viewers can perceive the environment. As we contemplate how best to engage people in reflecting on what it means to live in a sustainable fashion, it is important that we consider the merits of particular rhetorical modes in environmental communication and how those approaches may engender concern or hopelessness, engagement or disengagement. One form of environmental communication that relies heavily on images, and that is growing in popularity, is documentary film. -

Introduction to Documentary Door Bill Nichols

[Geschiedenis voor een breed publiek] [2011-2012] Professor: Prof. Tom Verschaffel Handboek: DE GROOT, J., Consuming History. Historians and Heritage in Contemporary Popular Culture, 2009. Gemaakt door: Andrea Bardyn (geupload, niet zelf gemaakt) Opmerkingen: PDF van de eerste editie van het boek Introduction to Documentary door Bill Nichols. Noch Project Avalon, noch het monitoraat, noch Historia of eender ander individu of instelling zijn verantwoordelijk voor de inhoud van dit document. Maak er gebruik van op eigen risico. Nichols, Intro to Documentary 8/9/01 10:18 AM Page i Introduction to Documentary Nichols, Intro to Documentary 8/9/01 10:18 AM Page ii Nichols, Intro to Documentary 8/9/01 10:18 AM Page iii Bill Nichols Introduction to Documentary Indiana University Press | Bloomington & Indianapolis Nichols, Intro to Documentary 8/9/01 10:18 AM Page iv This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://iupress.indiana.edu Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2001 by Bill Nichols All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

VSW 16Mm Master Inventory Alphabetical Inventory

VSW 16mm Master Inventory_Alphabetical Inventory Accesion ID Title Location # Format Footage 2016:05:4491 30891 06:39:01 16 650 2016:01:0940 Apple Dolls 01:37:01 16 700 2016:02:1366 Pimental Discusses the Hydrogen Atom 02:17:02 16 900 2016:01:0744 ...And Contact is Made... 01:31:01 16 400 2016:01:1019 "200" 01:39:02 16 800 2016:01:2222 "A": Un Film de Jan Lenica 03:29:01 16 350 2016:03:2182 "Bob and Rhoda" 03:23:03 16 800 2016:03:2186 "Boss Isn't Coming to Dinner" 03:23:03 16 800 2016:03:2183 "Can't Lose" 03:23:03 16 800 2016:01:0588 "Feeding the World": Abundance and Shortage 01:22:02 16 400 2016:01:2757 "Funnies" #18 04:31:01 16 700 2016:01:2758 "Funnies" #19 04:31:01 16 450 2016:01:2759 "Funnies" #20 04:31:01 16 700 2016:01:2760 "Funnies" #21 04:31:01 16 400 2016:01:2761 "Funnies" #25 04:31:01 16 700 2016:01:2817 "Funnies" #27 04:30:02 16 400 2016:01:2818 "Funnies" #29 04:30:02 16 400 2016:01:2819 "Funnies" #30 04:30:03 16 400 2016:01:2762 "Funnies" #32 04:31:01 16 600 2016:01:2763 "Funnies" #37 04:32:01 16 400 2016:01:2764 "Funnies" #38 04:32:01 16 100 2016:01:2765 "Funnies" #40 04:32:01 16 600 2016:003:0115 "I Have a Dream" MLK 01:04:02 16 400 2016:03:1066 "I Was a Fugitive from a Chaingang" 01:47:01 16 2800 2016:03:1080 "In Remembrance: 01:42:02 16 1000 2016:03:2184 "Lou and that Woman" 03:23:03 16 800 2016:03:2185 "Lou Douses an Old Flame" 03:23:03 16 800 2016:03:2188 "Lou's Place" 03:23:03 16 800 9/4/2019 1 VSW 16mm Master Inventory_Alphabetical Inventory Accesion ID Title Location # Format Footage 2016:01:3500 "O" for Oxygen 01:37:03 16 650 2016:03:2187 "Phyllis Whips Inflation" 03:23:03 16 800 2016:03:2181 "Support Your Local Mother" 03:23:03 16 800 2016:03:2002 "They Meet Again": Dr. -

Films for History and Political Science, Fourth Edition

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 134 510 SO 009 747 AUTHOR Nagle, Richard W., Comp. TITLE Films for History and Political Science, Fourth Edition. INSTITUTLON Pennsylvania State Univ., University Park. Audio-Visual Services. PUB DATE 76 NOTE 123p. AVAILABLE FROM Audio Visual Services, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802 (free) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; Catalogs; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; *Filmographies; *Films; Global Approach; Higher Education; *History; *Political Science; Primary Education; *Reference Materials; Social Problems ABSTRACT Over 1,200 films related to history and political science are listed and described in this catalog. Content includes pollution, crime, civil rights, and other contemporaryconcerns; surveys of different nations; and philosophical views of thinkers. In the main body of the catalog, the films are listed alphabetically by title. For each entry, information is given on distributor's code, release date, running time, catalog number, and rental fee. A code indication of each film's potential audience (primary, elementary, junior high, senior high, college, and adult) follows a brief description of the film's content. MoSt of the films were made within the past 15 years, and they average 'between 20 and 70 minutes running time. A series list identifies groups of films producedon specific topics, such as China, exploring, man and his world, and profiles in courage. A subject index lists all films from the main section according to subject area, such as ancient world, black rights, cities, European history--renaissance and reformation, and religion.. Five order blanks are included at the end of the catalog. -

The Core Film Collection : 500 Titles Selected by the FLIC Board for a Medium-Sized Public Library

The Core Film Collection : 500 Titles Selected by the FLIC Board for a Medium-Sized Public Library PATRICIA H. MACKEY ALTHOUGHTHE MOTION PICTURE was invented in the late 1800s, the film is truly an art of the twentieth century, expanding both literally and figu- ratively to include various formats, imaginative technical achievements and a multiplicity of sources for acquiring the medium. The theatrical and reportage aspects of the motion picture were realized immediately, but audiences were slower to grasp the obvious concept of the film as a visual medium, made possible by a physical phenomenon known as the persistence of retinal impression. Indeed, film becomes magic, for the motion picture is not actually a motion picture, but a series of still photo- graphs which move through a projector at a rate of twenty-four frames per second, creating a visual impression of movement. The film has always been a public art, designed as a powerful com- munications tool accessible to large groups of people, involving empathy, identification and an immediate sense of recognition and emotional re- sponse from its viewers. The appeal of the film is irresistible, heightened by the intimacy of a darkened room and the closeness of strangers. As early as 1909, the motion picture was big business.l Originally providing a source of entertainment and novelty, the film industry moved toward areas of information, documentation and propaganda. But it was actually George Eastman’s development and marketing of 16mm film and equipment -less complicated, less bulky and less expensive than 35mm -which created the means for libraries to enter the film field. -

16Mm Films Call Number Shelf # 1492 $$Jmovie 6862-F 17660

16mm Films Call number Shelf # 1492 $$jMOVIE 6862-F 17660 1898 $$jMOVIE 2352-F 05521 1964 $$jMOVIE 667-F 18630 111th Street $$jMOVIE 6250-F 03952 1807, United States vs. Aaron Burr $$jMOVIE 3370-F 08099 1930's $$jMOVIE 7130-F 14277 1985 CLIO awards $$jMOVIE 2351-F 08801 220 blues $$jMOVIE 5206-F 09449 250,000 ways to destroy a child's life without leaving home. $$jMOVIE 1136-F 16434 330 million gods. $$jMOVIE 3532-F 08839 330 million gods. $$jMOVIE 3532-F 06678 3900 Million And One $$jMOVIE 2276-F 04617 67,000 dreams. $$jMOVIE 3906-F 19294 67,000 dreams. $$jMOVIE 3906-F 07683 67,000 dreams. $$jMOVIE 3906-F 04677 9 variations on a dance theme $$jMOVIE 4673-F 02561 A $$jMOVIE 5806-F 00326 A call for peace: The military budget and you $$jMOVIE 1712-F 05747 A case of suicide $$jMOVIE 1215-F 18622 A case of suicide $$jMOVIE 1215-F 06933 A case of suicide $$jMOVIE 1215-F 04857 A case of suicide $$jMOVIE 1215-F 03508 A chairy tale $$jMOVIE 1299-F 01966 A chairy tale $$jMOVIE 1299-F 01409 A chairy tale $$jMOVIE 1299-F 01336 A chairy tale $$jMOVIE 1299-F 01287 A chairy tale $$jMOVIE 1299-F 00789 A chairy tale $$jMOVIE 1299-F 00427 A Christmas carol. $$jMOVIE 4321-F 14170 A Christmas carol. $$jMOVIE 942-F 07995 A Christmas carol. $$jMOVIE 942-F 05784 A Christmas carol. $$jMOVIE 942-F 04389 A City awakens $$jMOVIE 5050-F 02409 A City farmstead $$jMOVIE 1193-F 08990 A communications primer $$jMOVIE 2562-F 02957 A Conversation with James B. -

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 2/8/11 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2005 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Mothlight, 1963 US Eyes, 1971 Dog Star Man, 1962 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, 1984