Visual Rhetoric in Environmental Documentaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perceptual Realism and Embodied Experience in the Travelogue Genre

Athens Journal of Mass Media and Communications- Volume 3, Issue 3 – Pages 229-258 Perceptual Realism and Embodied Experience in the Travelogue Genre By Perla Carrillo Quiroga This paper draws two lines of analysis. On the one hand it discusses the history of the This paper draws two lines of analysis. On the one hand it discusses the history of the travelogue genre while drawing a parallel with a Bazanian teleology of cinematic realism. On the other, it incorporates phenomenological approaches with neuroscience’s discovery of mirror neurons and an embodied simulation mechanism in order to reflect upon the techniques and cinematic styles of the travelogue genre. In this article I discuss the travelogue film genre through a phenomenological approach to film studies. First I trace the history of the travelogue film by distinguishing three main categories, each one ascribed to a particular form of realism. The hyper-realistic travelogue, which is related to a perceptual form of realism; the first person travelogue, associated with realism as authenticity; and the travelogue as a traditional documentary which is related to a factual form of realism. I then discuss how these categories relate to Andre Bazin’s ideas on realism through notions such as montage, duration, the long take and his "myth of total cinema". I discuss the concept of perceptual realism as a key style in the travelogue genre evident in the use of extra-filmic technologies which have attempted to bring the spectator’s body closer into an immersion into filmic space by simulating the physical and sensorial experience of travelling. -

Amazon Adventure 3D Press Kit

Amazon Adventure 3D Press Kit SK Films: Facebook/Instagram/Youtube: Amber Hawtin @AmazonAdventureFilm Director, Sales & Marketing Twitter: @SKFilms Phone: 416.367.0440 ext. 3033 Cell: 416.930.5524 Email: [email protected] Website: www.amazonadventurefilm.com 1 National Press Release: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AMAZON ADVENTURE 3D BRINGS AN EPIC AND INSPIRATIONAL STORY SET IN THE HEART OF THE AMAZON RAINFOREST TO IMAX® SCREENS WITH ITS WORLD PREMIERE AT THE SMITHSONIAN’S NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY ON APRIL 18th. April 2017 -- SK Films, an award-winning producer and distributor of natural history entertainment, and HHMI Tangled Bank Studios, the acclaimed film production unit of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, announced today the IMAX/Giant Screen film AMAZON ADVENTURE will launch on April 18, 2017 at the World Premiere event at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. The film traces the extraordinary journey of naturalist and explorer Henry Walter Bates - the most influential scientist you’ve never heard of – who provided “the beautiful proof” to Charles Darwin for his then controversial theory of natural selection, the scientific explanation for the development of life on Earth. As a young man, Bates risked his life for science during his 11-year expedition into the Amazon rainforest. AMAZON ADVENTURE is a compelling detective story of peril, perseverance and, ultimately, success, drawing audiences into the fascinating world of animal mimicry, the astonishing phenomenon where one animal adopts the look of another, gaining an advantage to survive. "The Giant Screen is the ideal format to take audiences to places that they might not normally go and to see amazing creatures they might not normally see,” said Executive Producer Jonathan Barker, CEO of SK Films. -

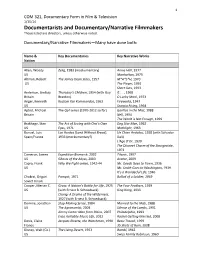

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

485 Svilicic.Vp

Coll. Antropol. 37 (2013) 4: 1327–1338 Original scientific paper The Popularization of the Ethnological Documentary Film at the Beginning of the 21st Century Nik{a Svili~i}1 and Zlatko Vida~kovi}2 1 Institute for Anthropological Research, Zagreb, Croatia 2 University of Zagreb, Academy of Dramatic Art, Zagreb, Croatia ABSTRACT This paper seeks to explain the reasons for the rising popularity of the ethnological documentary genre in all its forms, emphasizing its correlation with contemporary social events or trends. The paper presents the origins and the de- velopment of the ethnological documentary film in the anthropological domain. Special attention is given to the most in- fluential documentaries of the last decade, dealing with politics: (Fahrenheit 9/1, Bush’s Brain), gun control (Bowling for Columbine), health (Sicko), the economy (Capitalism: A Love Story), ecology An Inconvenient Truth) and food (Super Size Me). The paper further analyzes the popularization of the documentary film in Croatia, the most watched Croatian documentaries in theatres, and the most controversial Croatian documentaries. It determines the structure and methods in the making of a documentary film, presents the basic types of scripts for a documentary film, and points out the differ- ences between scripts for a documentary and a feature film. Finally, the paper questions the possibility of capturing the whole truth and whether some documentaries, such as the Croatian classics: A Little Village Performance and Green Love, are documentaries at all. Key words: documentary film, anthropological topics, script, ethnographic film, methods, production, Croatian doc- umentaries Introduction This paper deals with the phenomenon of the popu- the same time, creating a work of art. -

Drama Directory

2015 UPDATE CONTENTS Acknowlegements ..................................................... 2 Latvia ......................................................................... 124 Introduction ................................................................. 3 Lithuania ................................................................... 127 Luxembourg ............................................................ 133 Austria .......................................................................... 4 Malta .......................................................................... 135 Belgium ...................................................................... 10 Netherlands ............................................................. 137 Bulgaria ....................................................................... 21 Norway ..................................................................... 147 Cyprus ......................................................................... 26 Poland ........................................................................ 153 Czech Republic ......................................................... 31 Portugal ................................................................... 159 Denmark .................................................................... 36 Romania ................................................................... 165 Estonia ........................................................................ 42 Slovakia .................................................................... 174 -

PENN ROAR January 2013 Volume 3 Pennsylvania’S Royalty Ow Ners Action Report Issue 1

PENN ROAR January 2013 Volume 3 Pennsylvania’s Royalty Ow ners Action Report Issue 1 Penn ROAR, 359 Route 106 Greenfield Twp, PA 18407 [email protected] 570-267-4083 for advertising Inside NARO-PA premiere party & January 22 @ Montrose VFW … see page 5 This Issue Page 3… Market Enhancement Clauses and ‘Deductions’: New Well Owners Do I Have a Claim Against the Gas Company for Improper Booklet Answers Many Questions Royalty Payments? By: Douglas A. Clark, The Clark Law Firm, PC Page 4… An extremely hot issue at the present New Documentary addressing royalty calculation in effort to Aims to Correct time involves post-production costs or eliminate or reduce post-production costs. “Lies” and “deductions” that landowners are seeing One common royalty addendum “Misinformation” subtracted from their gas royalty checks. provision, often referred to as a “Market Typically, boilerplate Oil and Gas Leases Enhancement Clause”, began to surface in offered to landowners clearly permit the gas Page 6… many Oil and Gas Lease Addendum. The New Tax Rates & company to deduct post-production costs for “Market Enhancement Clause” provides as Rules to Affect Your the cost of producing, gathering, storing, Wallet for 2013 separating, treating, follows: dehydrating, processing, MARKET Page 7… transporting and marketing ENHANCEMENT Legislative Update the oil and gas. CLAUSE In the 2010 Pennsylvania All oil, gas or Page 8… Supreme Court’s decision in other proceeds accruing Marcellus Shale Kilmer v Elexco Land to Lessor under this lease boom sparks Services, Inc. et al., 605 or by state law shall be student's interest in oil, gas law Pa.413, 990 A.2D 147 (Pa. -

Sundance Institute Announces Major New Initiatives for Films on Climate Change and the Environment

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: April 21, 2016 Janine Der Bogosian 310.360.1981 [email protected] Sundance Institute Announces Major New Initiatives for Films on Climate Change and the Environment Supported by Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, Kendeda Fund, Discovery Channel, Code Blue Foundation and Joy Family Foundation Catching the Sun is First Project to Receive Support from Robert Rauschenberg Foundation; Documentary Premieres Tomorrow on Netflix for Earth Day Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute announced today a new initiative for films and emerging media projects exploring stories related to the urgent need for action with regard to the environment, conservation and climate change. Building on more than three decades of the Institute’s championing of independent stories focused on the environment, these grants to support new projects are led by founding support from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and include additional support from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Kendeda Fund, Discovery Channel, Code Blue Foundation and the Joy Family Foundation. Robert Redford, President & Founder of Sundance Institute, said, “We want this financial and creative support to stimulate the next wave of independent film and visual storytelling that inspires action on one of the most urgent issues of our time: the long-term, sustainable health of our planet.” The Institute’s new program with the Rauschenberg Foundation will identify and support the creation of four projects that tackle the subject of climate change and inspire action. As part of this joint initiative, filmmakers and climate change experts will gather together for a Climate Change Lab in 2017 at renowned American artist Robert Rauschenberg’s estate and studio in Captiva Island, Florida. -

The Plight of Our Planet the Relationship Between Wildlife Programming and Conservation Efforts

! THE PLIGHT OF OUR PLANET fi » = ˛ ≈ ! > M Photo: https://www.kmogallery.com/wildlife/2 = 018/10/5/ry0c9a1o37uwbqlwytiddkxoms8ji1 u f f ≈ f Page 1 The Plight of Our Planet The Relationship Between Wildlife Programming And Conservation Efforts: How Visual Storytelling Can Save The World By: Kelsey O’Connell - 20203259 In Fulfillment For: Film, Television and Screen Industries Project – CULT4035 Prepared For: Disneynature, BBC Earth, Netflix Originals, National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Animal Planet, Etc. Page 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I cannot express enough gratitude to everyone who believed in me on this crazy and fantastic journey; everything you have done has molded me into the person I am today. To my family, who taught me to seek out my own purpose and pursue it wholeheartedly; without you, I would have never taken the chance and moved to England for my Masters. To my professors, who became my trusted resources and friends, your endless and caring teachings have supported me in more ways than I can put into words. To my friends who have never failed to make me smile, I am so lucky to have you in my life. Finally, a special thanks to David Attenborough, Steve Irwin, Terri Irwin, Jane Goodall, Peter Gros, Jim Fowler, and so many others for making me fall in love with wildlife and spark a fire in my heart for their welfare. I grew up on wildlife films and television shows like Planet Earth, Blue Planet, March of the Penguins, Crocodile Hunter, Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom, Shark Week, and others – it was because of those programs that I first fell in love with nature as a kid, and I’ve taken that passion with me, my whole life. -

Elon, “Salt”, Piedmont and Lithium Dreams – Part 1 This Is Part 1 of a Multi Part Series That Will Be Written Between Now and 2023

Elon, “Salt”, Piedmont and Lithium Dreams – Part 1 This is part 1 of a multi part series that will be written between now and 2023. I will follow both Tesla’s and Piedmont’s lithium journeys with interest. If I am wrong, it will be my pleasure to write a mea culpa as I have done before. Since being a guest on TC and Georgia’s Podcast a few weeks ago, I have been exposed to the anti Tesla crowd for the first time. I made it clear before agreeing to participate that I have no axe to grind with Tesla or Elon Musk other than the nonsensical statements about lithium made on Battery Day. The hosts of Chartcast were absolutely professional with me and have been on all the episodes I have listened to. I would not hesitate to be a guest again in the future. What I was not prepared for was the small percentage of what appear to be slightly unhinged Chartcast listeners that decided I needed to hear their “Elon rants”. That is no fault of the podcast hosts. At some level Tesla seems a cult on par with the best on them. We live in a celebrity culture driven largely by social media and inCreasingly shorter “news cycles”. A world where facts are often hard to come by and comments, no matter how far off base, by someone like Elon Musk will be taken as “gospel” by a significant percentage of his ~ 40 million twitter followers. Elon along with “sidekick of the moment” Drew Baglino shared the Battery Day stage to declare their latest magic trick - creating “instant lithium”. -

Racing Extinction

Racing Extinction Directed by Academy Award® winner Louie Psihoyos And the team behind THE COVE RACING EXTINCTION will have a worldwide broadcast premiere on The Discovery Channel December 2nd. Publicity Materials Are Available at: www.racingextinction.com Running Time: 94 minutes Press Contacts: Discovery Channel: Sunshine Sachs Jackie Lamaj NY/LA/National Office: 212.548.5607 Office: 212.691.2800 Email: [email protected] Tiffany Malloy Email: [email protected] Jacque Seaman Vulcan Productions: Email: [email protected] Julia Pacetti Office: 718.399.0400 Email: [email protected] 1 RACING EXTINCTION Synopsis Short Synopsis Oscar®-winning director Louie Psihoyos (THE COVE) assembles a team of artists and activists on an undercover operation to expose the hidden world of endangered species and the race to protect them against mass extinction. Spanning the globe to infiltrate the world’s most dangerous black markets and using high tech tactics to document the link between carbon emissions and species extinction, RACING EXTINCTION reveals stunning, never-before seen images that truly change the way we see the world. Long Synopsis Scientists predict that humanity’s footprint on the planet may cause the loss of 50% of all species by the end of the century. They believe we have entered the sixth major extinction in Earth’s history, following the fifth great extinction which took out the dinosaurs. Our era is called the Anthropocene, or “Age of Man,” because evidence shows that humanity has sparked a cataclysmic change of the world’s natural environment and animal life. Yet, we are the only ones who can stop the change we have created. -

Portada Tesis Copia.Psd

EL PAPEL EN EL GEIDŌ Enseñanza, praxis y creación desde la mirada de Oriente TESIS DOCTORAL María Carolina Larrea Jorquera Directora: Dra. Marina Pastor Aguilar UNIVERSITAT POLITÈCNICA DE VALÈNCIA FACULTAT DE BELLES ARTS DE SANT CARLES DOCTORADO EN ARTE: PRODUCCIÓN E INVESTIGACIÓN Valencia, Junio 2015 2 A mis cuchisobrinos: Mi dulce Pablo, mi Fruni Fru, Emilia cuchi y a Ema pomonita. 3 4 Agradecimientos Mi más sincera gratitud a quienes a lo largo de estos años me han apoyado, aguantado y tendido una mano de diferentes maneras en el desarrollo y conclusión de esta tesis. Primero agradecer a mi profesor y mentor Timothy Barrett, por enseñarme con tanta generosidad el oficio y arte del papel tradicional hecho a mano japonés y europeo, y por compartir sus experiencias como aprendiz en nuestros trayectos hacia Oakdale. A Claudia Lira por hablarme del camino, a Sukey Hughes por compartir sus vivencias como aprendiz y su percepción del oficio, a Hiroko Karuno por mostrarme con dedicación el arte del shifu, a Paul Denhoed y Maki Yamashita por guiarme y recibirme amablemente en su casa, a Rina Aoki por su buen humor, hospitalidad y amistad, a Lauren Pearlman por socorrerme en el idioma japonés, a Clara Ruiz por abrirme las puertas de su casa, por su amistad y buena cocina, a Nati Garrido por ayudarme a cuidar de mi salud y que no me falte el deporte, a Miguel A. por llenarme el corazón de sonrisas y lágrimas que valen la pena atesorar, Clara Castillo, Alfredo Llorens y Ana Sánchez Montabes, por su amistad y cariño, a José Borge por enseñarme que Word tiene muchas más herramientas, a Marina Pastor por sus consejos en la mejor manera de mostrar la información, a mi familia y a mis amigos chilenos y valencianos que con su buena energía me han dado mucha fuerza para terminar este trabajo. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism.