A Tale of the Lake District Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Livestock Schedule

Livestock Schedule August Bank Holiday Monday 26th August 2019 www.hopeshow.co.uk 1 Schedule and Entry Forms The Livestock Schedule and Entry Forms can be downloaded from www.hopeshow.co.uk Completed Entry Forms CLOSING DATE FOR ENTRIES: 12TH AUGUST 2019 Please send completed Entry Forms and a stamped addressed envelope by post to: Miss E Priestley, Dale Cottage, The Dale, Stoney Middleton, Hope Valley S32 4TF Email: [email protected] Tel: 07890 264 046 All Cattle Entry Fees - £7.00/class/entry All Sheep Entry Fees - £2.00/class/entry Fleece and Hay Entry Fees - £2.00/class/entry Young Handler classes are free to enter Hope Valley Young Farmers classes are free to enter Cheques should be made payable to Hope Sheepdog Trails and Agricultural Society. Alternatively you may wish to pay electronically via online banking, please quote “livestock” as the reference and state that you have done so on your entry form. Account number 95119299 Sort code 60-10-19 Entry wristbands will be posted to entrants shortly before the Show. 2 Cup Winners Winners of cattle and sheep breed championships, cattle special prizes, beef and sheep interbreed championships, HVYFC cattle and cade lamb classes and Hope Show Sheep Young Handlers classes are cordially invited to receive their cup(s) from Hope Show’s President in the Grand Parade. The Grand Parade begins at 3:30pm (unless otherwise announced). Cattle class winners will be marshalled in the cattle ring at 3.00pm. Sheep class winners will be marshalled in the MV accredited or Non MV accredited section of the Parkin ring as appropriate at 2.30pm. -

Implications of Agri-Environment Schemes on Hefting in Northern England

Case Study 3 Implications of Agri-environment Schemes on Hefting in Northern England This case study demonstrates the implications of agri-environmental schemes in the Lake District National Park. This farm is subject of an ESA (Environmentally Sensitive Area) agreement. The farm lies at the South Eastern end of Buttermere lake in the Cumbrian Mountains. This is a very hard fell farm in the heart of rough fell country, with sheer rock face and scree slopes and much inaccessible land. The family has farmed this farm since 1932 when the present farmer’s grandfather took the farm, along with its hefted Herdwick flock, as a tenant. The farm was bought, complete with the sheep in 1963. The bloodlines of the present flock have been hefted here for as long as anyone can remember. A hard fell farm The farmstead lies at around 100m above sea level with fell land rising to over 800m. There are 20ha (50 acres) of in-bye land on the farm, and another 25ha (62 acres) a few miles away. The rest of the farm is harsh rough grazing including 365ha (900 acres) of intake and 1944ha (4,800acres) of open fell. The farm now runs two and a half thousand sheep including both Swaledales and Herdwicks. The farmer states that the Herdwicks are tougher than the Swaledales, producing three crops of lambs to the Swaledale’s two. At present there are 800 ewes out on the fell. Ewes are not tupped until their third year. Case Study 3 Due to the ESA stocking restriction ewe hoggs and gimmer shearlings are sent away to grass keep for their first two winters, from 1 st November to 1 st April. -

Newlands Valley Walk

Newlands Valley Walk You can start this walk from virtually anywhere in the Newlands valley; I started from a couple of our Lake District cottages at Birkrigg on the Newlands Pass. Walk down the road in the direction of Keswick, you will soon come to a tight bend at Rigg Beck where the ‘Old Purple House’ used to stand. There is now a Grand Designs style house on the site but the purple colour remains on the roof garden and the front door. Carry on along the pass till you come across a gate on the right hand side and a finger post indicating a footpath beyond the gate. The path leads down into the valley fields and across a minor road. A track climbs up the other side of the valley and emerges at Skelgill. Walk through the farmyard and turn immediately back on yourself to join the path that runs alongside Catbells, towards the old mines at Yewthwaite. After about half a mile, the path descends into Little Town where you can enjoy a well earned cup of tea at the farm tea room. Now there are two options from Little Town. For a longer walk, go back up onto the track and carry on down the valley. This will take you to the old mines at Goldscope where you can peer into the open shafts on the side of Hindscarth. Alternatively you can walk along the road towards Chapel Bridge and stroll down the lane to the pretty little church. The church serves tea and cake on weekends and during the summer. -

English Nature Research Report

3.2 Grazing animals used in projects 3.2.1 Species of gradng animals Some sites utilised more than one species of grazing animals so the results in Table 5 are based on 182 records. The majority of sites used sheep and/or cattle and these species were used on an almost equal number of sites, Ponies were also widely used but horses and goats were used infrequently and pigs were used on just 2 sites. No other species of grazing livestock was recorded (a mention of rabbits was taken to refer to wild populations). Table 5. Species of livestock used for grazing Sheep Cattle Equines Goats Pigs Number of Sites 71 72 30 7 2 Percentage of Records 39 40 16 4 I 3.2.2 Breeds of Sheep The breeds and crosses of sheep used are shown in Table 6. A surprisingly large number of 46 breeds or crosses were used on the 71 sites; the majority can be considered as commercial, although hardy, native breeds or crosses including hill breeds such as Cheviot, Derbyshire Gritstone, Herdwick, Scottish Blackface, Swaledale and Welsh Mountain, grassland breeds such as Beulah Speckled Face, Clun Forest, Jacob and Lleyn and down breeds such as Dorset (it was not stated whether this was Dorset Down or Dorset Horn), Hampshire Down and Southdown. Continental breeds were represented by Benichon du Cher, Bleu du Maine and Texel. Rare breeds (i.e. those included on the Rare Breeds Survival Trust’s priority and minority lists) were well represented by Hebridean, Leicester Longwool, Manx Loghtan, Portland, Shetland, Soay, Southdown, Teeswater and Wiltshire Horn. -

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

Agricultural Department Sheep Beltex Bluefaced

AGRICULTURAL DEPARTMENT Skelton Show Holding No. 08/173/8000 Entries accepted Only on Official Forms and MUST be accompanied by Entry Fees and paid at time of entry. Please state both Ear Tag and Holding Numbers for all livestock entered and name(s) of handlers and attendants on Show Day must be clearly stated on movement forms. Livestock not to leave the ground before 3-30 p.m. Judging commences 9-30 a.m. prompt, commencing with young handlers. Note: Sheep Trophies will be awarded in the Grand Parade The Committee wish to thank all Sponsors of Classes. Any Ministry Rules or Restrictions must be observed. Overall Referee: Mr G. & Mrs H. Miller, Penruddock The Overall Champion of Champions - Sheep, Cattle & Heavy Horse Sections Only for the John Mounsey Memorial Perpetual Trophy in the Main Ring at 2pm Judge: Mr G. and Mrs H. Miller, Penruddock SHEEP Skelton Show is licensed under the Animal Gatherings Order 2010. All current Defra regulations must be strictly adhered to. Entries: £2.00 (£8.00 minimum) Prizes: 1st £15.00, 2nd £10.00, 3rd £5.00, 4th prize of 3.00 where 7 + entries in any class All Group Prizes 1st £10.00, 2nd £6.00 3rd £4.00, Unless otherwise stated. Entries for Suffolk, Texel, Zwartble, Beltex & Charollais are restricted to accredited flocks in accordance with Maedi-Visna accredited flocks scheme BELTEX All sheep to be Defra MV Accredited. Registered flock number to be included Judge: Mrs K. Shuttleworth, Gargrave 300. Aged Ram 301. Shearling Ram 302. Ram Lamb 303. Ewe (to have reared lamb this year) 304. -

30297-Nidderdale 2012 Schedule 5:Layout 1

P R O G R A M M E (Time-table will be strictly adhered to where possible) ORDER OF JUDGING: Approx. 08.00 a.m. Breeding Hunters (commencing with Ridden Hunter Class) 09.00 a.m. Sheep Dog Trials 09.00 a.m. Carcass Class 09.00 a.m. Dogs Approx. 09.00 a.m. Riding and Turnout Approx. 09.00 a.m. Coloured Horse/Pony In-hand 09.15 a.m. Young Farmers’ Cattle 09.30 a.m. Dry Stone Walling Ballot 09.30 a.m. Beef Cattle (Local) 09.45 a.m. Sheep Approx. 10.00 a.m. All Other Cattle Judging commences Approx. 10.00 a.m. Children’s Riding Classes Approx. 10.00 a.m. Heavy Weight Agricultural Horses 10.00 a.m. Goats 10.00 a.m. Produce, Home Produce and Crafts (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Flowers, Vegetables and Farm Crops (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Poultry, Pigeons and Rabbits 10.30 a.m. ‘Pateley Pantry’ Stands Approx. 10.45 a.m. Mountain & Moorland 11.00 a.m. Pigs Approx. 11.00 a.m. Ridden Coloured 11.00 a.m. Trade Stands 1.15 p.m. Junior Shepherd/Shepherdess Classes (judged at the sheep pens) Approx. 2.00 p.m. Childrens’ Pet Classes (judged in the cattle rings) 2.00 p.m. Sheep - Supreme Championship MAIN RING ATTRACTIONS: 08.00-12.00 Judging - Horse and Pony classes 12.00-12.35 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 12.35-12.55 Terrier Racing 12.55-1.30 ATV Manoeuvrability Test 1.30-2.00 Young Farmers Mascot Football 2.00-2.20 Parade of Fox Hounds by West of Yore Hunt & Claro Beagles 2.20-3.00 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 3.00-3.30 GRAND PARADE AND PRESENTATION OF TROPHIES (Excluding Sheep, Goats, Pigs, Produce and WI) Parade of Tractors celebrating 8 decades of Nidderdale Young Farmers Club 3.30- Show Jumping OTHER ATTRACTIONS: Meltham & Meltham Mills Band playing throughout the day 12.00-12.15 St Cuthbert’s Primary School Band 12.15-1.15 Lofthouse & Middlesmoor Silver Band Forestry Exhibition Heritage Marquee Small Traders/Craft Marquee Pateley Pantry Marquee with Cookery Demonstrations 11.00 a.m. -

BMC Veterinary Research Biomed Central

BMC Veterinary Research BioMed Central Research article Open Access Associations between lamb survival and prion protein genotype: analysis of data for ten sheep breeds in Great Britain Simon Gubbins1, Charlotte J Cook2, Kieran Hyder2, Kay Boulton3, Carol Davis3, Eurion Thomas4, Will Haresign5, Stephen C Bishop6, Beatriz Villanueva7 and Rachel D Eglin*2 Address: 1Institute for Animal Health, Pirbright Laboratory, Ash Road, Pirbright, Surrey, GU24 0NF, UK, 2Centre for Epidemiology and Risk Analysis, Veterinary Laboratories Agency, Woodham Lane, New Haw, Addlestone, Surrey, KT15 3NB, UK, 3Meat and Livestock Commission, Winterhill House, Snowdon Drive, Milton Keynes, MK6 1AX, UK, 4Innovis Ltd, Peithyll Centre, Capel Dewi, Aberystwyth, Ceredigon, SY23 3HU, UK, 5Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Llanbadarn Campus, Aberystwyth, Ceredigon, SY23 3AL, UK, 6The Roslin Institute and R(D)SVS, University of Edinburgh, Roslin BioCentre, Roslin, Midlothian, EH25 9PS, UK and 7Scottish Agricultural College, West Mains Road, Edinburgh, EH9 3JG, UK Email: Simon Gubbins - [email protected]; Charlotte J Cook - [email protected]; Kieran Hyder - [email protected]; Kay Boulton - [email protected]; Carol Davis - [email protected]; Eurion Thomas - [email protected]; Will Haresign - [email protected]; Stephen C Bishop - [email protected]; Beatriz Villanueva - [email protected]; Rachel D Eglin* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 21 January 2009 Received: 31 July 2008 Accepted: 21 January 2009 BMC Veterinary Research 2009, 5:3 doi:10.1186/1746-6148-5-3 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1746-6148/5/3 © 2009 Gubbins et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. -

The Lake District Atlantis What Lies Beneath Haweswater Reservoir?

http://www.discoveringbritain.org/connectors/system/phpthumb.php?src=co- ntent%2Fdiscoveringbritain%2Fimages%2FNess+Point+viewpoint%2FNess+- Point+test+thumbnail.jpg&w=100&h=80&f=png&q=90&far=1&HTTP_MODAUTH- =modx562284b1ecf2c4.82596133_2573b1626b27792.46804285&wctx=mgr&source=1 Viewpoint The Lake District Atlantis Time: 15 mins Region: North West England Landscape: rural Location: Bowderthwaite Bridge, Mardale, nearest postcode CA10 2RP Grid reference: NY 46793 11781 Keep and eye out for: Evidence of glaciation revealed in the smoothness of some of the boulders and rocks lying around the water’s edge Visitors to Haweswater receive little indication of the history of this remote valley. Like many of the other valleys in the Lake District, we might assume it is purely of volcanic and glacial origin, which indeed it is. But a quick glance at the map tells us that rather than being a natural lake we are looking at a reservoir. The passage of time has softened the shoreline of the lake to the extent that it now appears perfectly natural. However, when the water level is low little clues to the past may emerge... What lies beneath Haweswater reservoir? When the water level is low the tops of old stone walls stick out of the water like the scales of crocodiles basking in the sun. The stone walls are in fact the remnants of a lost village. The valley used to have a small hamlet at its head – Mardale Green – but this was submerged in the late 1930s when the water level of the valley’s original lake was raised to form a reservoir. -

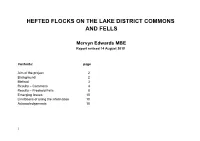

Hefted Flocks on the Lake District Commons and Fells

HEFTED FLOCKS ON THE LAKE DISTRICT COMMONS AND FELLS Mervyn Edwards MBE Report revised 14 August 2018 Contents: page Aim of the project 2 Background 2 Method 3 Results – Commons 4 Results – Freehold Fells 8 Emerging Issues 10 Limitations of using the information 10 Acknowledgements 10 1 HEFTED FLOCKS ON THE LAKE DISTRICT COMMONS AND FELLS Mervyn Edwards MBE Report revised 14 August 2018 Aim of the project The aim was to strengthen the knowledge of sheep grazing practices on the Lake District fells. The report is complementary to a series of maps which indicate the approximate location of all the hefted flocks grazing the fells during the summer of 2016. The information was obtained by interviewing a sample of graziers in order to illustrate the practice of hefting, not necessarily to produce a strictly accurate record. Background The basis for grazing sheep on unenclosed mountain and moorland in the British Isles is the practice of hefting. This uses the homing and herding instincts of mountain sheep making it possible for individual flocks of sheep owned by different farmers to graze ‘open’ fells with no physical barriers between these flocks. Shepherds have used this as custom and practice for centuries. Hefted sheep, or heafed sheep as known in the Lake District, have a tendency to stay together in the same group and on the same local area of land (the heft or heaf) throughout their lives. These traits are passed down from the ewe to her lambs when grazing the fells – in essence the ewes show their lambs where to graze. -

WEEKLY NEWS 13 FEBRUARY 2021 Top Price Swaledale in Lamb

015242 61444/ 61246 (Sale Days) www.benthamauction.co.uk [email protected] WEEKLY NEWS 13TH FEBRUARY 2021 Photo by Linda Allan Top Price Swaledale In Lamb Shearling from EC Coates realising £2600 AUCTIONEERS: Stephen J Dennis Mobile: 07713 075 661 Greg MacDougall Mobile: 07713 075 664 Will Alexander Mobile: 07590 876 849 www.benthamauction.co.uk Saturday 6th February INDIVIDUAL IN LAMB SHEEP 57 FORWARD BREED TOP FROM AV Teeswater Shlgs £160 P Murray, Arcleton £160 BFL Shlgs £1850 AC & K Pye & Son, Abbeystead £848 BFL Hoggs £1800 WM Hutchinson & Son, Kirkby Stephen £1150 Swale Ewes £400 AH Price & Son, Clapham £320 Swale Shlgs £2600 EC Coates, Richmond £936 Swale Hoggs £1200 EC Coates, Richmond £817 Herdwick Ewes £420 D & J Wilson, Penrith £273 Herdwick Shlgs £900 D & J Wilson, Penrith £417 Herdwick Hoggs £300 D & J Wilson, Penrith £191 Cheviot Shlgs £500 KO Stones, Marrick £463 Auctioneer’s Report (Stephen Dennis): The Annual Sale of Individual In Lamb Sheep went off with a bang with a flying trade and a complete clearance of all breeds. The sale started with BFL which topped at £1850 for an in lamb shearling scanned for three from the Emmetts Flock from AC & K Pye. Messrs Booth, Smearsett Flock, sold an in lamb shearling to £1300 whilst R & PE Hargreaves, Barley sold to £1000. BFL Hoggs from the Redgate Flock of WM Hutchinson sold to £1800 and £1600. The Association Sale of Swaledale Sheep peaked at £2600 for a Bull & Cave sired shearling carrying twins to Stonesdale Governor find- ing a new home with Frank Brennand of Ellerbeck, who also bought a gimmer hogg from the same home sired by Keld-side Quantum at £1050. -

RR 01 07 Lake District Report.Qxp

A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas Integrated Geoscience Surveys (North) Programme Research Report RR/01/07 NAVIGATION HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are bookmarked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub-headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each figure, plate or table caption to the first place that figure, plate or table is mentioned in the text and from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RESEARCH REPORT RR/01/07 A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the District and adjacent areas Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2004. D Millward Keywords Lake District, Lower Palaeozoic, Ordovician, Devonian, volcanic geology, intrusive rocks Front cover View over the Scafell Caldera. BGS Photo D4011. Bibliographical reference MILLWARD, D. 2004. A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas. British Geological Survey Research Report RR/01/07 54pp.