Arabic Gospels in Italy • Wangechi Mutu • Lorena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Regional Economic Development Council Awards

2015 Regional Economic Development Council Awards Governor Andrew M. Cuomo 1 2 Table of Contents Regional Council Awards Western New York .........................................................................................................................12 Finger Lakes ...................................................................................................................................28 Southern Tier ..................................................................................................................................44 Central New York ..........................................................................................................................56 Mohawk Valley ...............................................................................................................................68 North Country .................................................................................................................................80 Capital Region ................................................................................................................................92 Mid-Hudson ...................................................................................................................................108 New York City ............................................................................................................................... 124 Long Island ................................................................................................................................... -

Illustrations

Illustrations BOOK ONE FOLLOWING PAGE 338 I. Mid-seventeenth-century map of Asia 2. Willem Blaeu's map of Asia 3. Map of the Mughul Empire, from Dapper's Asia, 1681 4. South and Southeast Asia, fromJohan Blaeu's Atlas major, 1662 5. Ceylon and the Maldives, from Sanson d'Abbeville's L'Asie, 1652 6. Continental Southeast Asia, from Morden's Geography Rectified, 1688 7. Course of the Menam, from La Loubere's Du royaume de Siam, 1691 8. Malacca and its environs, from Dampier's Voyages, 1700 9. The Moluccas, from Blaeu's Atlas major 10. Asia from Bay of Bengal to the Marianas, from Thevenot's Relations, 1666 II. Japan and Korea, from Blaeu's Atlas major 12. Harbor of Surat 13· Dutch factory at Surat 14· Market at Goa 15· English fort at Bombay 16. Harbor and wharf of Arakan 17· Batavia, ca. 1655 18. Amboina and its inhabitants 19· Dutch factory at Banda 20. Tidore and its fort 21. Dutch envoys in Cambodia 22. Fort Zeelandia in Taiwan 23· Dutch ambassadors in Peking, 1656 [xvii] Illustrations 24. Macao 25. Canton 26. Dutch factory at Hirado 27. Dutch factory on Deshima 28. Palanquins 29. Merchants of Bantam 30. Man and woman of Goa 3 I. Chinese merchant couple ]2. Dutch fleet before Bantam in 1596 33. Thee (tea), or cha, bush 34. King of Ternate's banquet for the Dutch, 1601 35. Coins of Siam 36. 1601 Malay-Latin vocabulary 37. 1672 Oriental-Italian vocabulary 38. Warehouse and shipyard of Dutch East India Company in Amsterdam 39. -

Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R

THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ANIMAL ETHICS SERIES Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK Priscilla N. Cohn Pennsylvania State University Villanova, PA, USA Associate Editor Clair Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Tis series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifcally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14421 Kenneth R. Valpey Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Oxford, UK Te Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-030-28407-7 ISBN 978-3-030-28408-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28408-4 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE JANUARY 2019 Name: Alejandro Garcia Address: 303 Crawford Avenue Syracuse, NY 13224 Telephone: Office: (315) 443-5569 Born: Brownsville, Texas April 1, 1940 Academic Unit: School of Social Work Academic Specialization: Social Policy, Gerontology, Human Diversity Education: Ph.D., Social Welfare Policy, The Heller School for Advanced Studies in Social Welfare, Brandeis University (1980) Dissertation title: "The Contribution of Social Security to the Adequacy ` of Income of Elderly Mexican Americans." Adviser: Professor James Schulz. M.S.W., Social Work, School of Social Work, California State University at Sacramento (1969) B.A., The University of Texas at Austin (1963) Graduate, Virginia Satir's International AVANTA Process Institute, Crested Butte, Colorado (1987) Membership in Professional and Learned Societies: Academy of Certified Social Workers American Association of University Professors Council on Social Work Education The Gerontological Society of America National Association of Social Workers Association of Latino and Latina Social Work Educators Professional Employment: October 2015-present Jocelyn Falk Endowed Professor of Social Work, School of Social Work Syracuse University 1983 to present: Professor (Tenured), School of Social Work, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 1994-2002 Chair, Gerontology Concentration, School of Social Work, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY Garcia cv p. 2 1999, 2000 Adjunct faculty, Smith College School for Social Work Northampton, MA 1984-91 Faculty, Elderhostel, Le Moyne College, Syracuse, NY 1978-1983 Associate Professor, School of Social Work, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 1975-1978 Instructor, Graduate School of Social Work Boston College, Boston, MA 1977-1978 Adjunct Assistant Professor of Social Work, Graduate School of Social Work, Boston University, Boston, MA 1977-1978 Special Lecturer in Social Policy. -

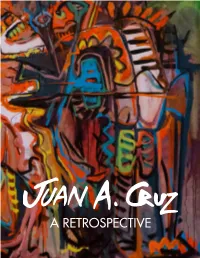

A Retrospective

A RETROSPECTIVE A RETROSPECTIVE This catalogue was published on the occasion of the exhibition Juan A. Cruz: A Retrospective Organized by DJ Hellerman and on view at the Everson Museum of Art, May 4 – August 4, 2019 Copyright Everson Museum of Art, 2019 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019946139 ISBN 978-0-9978968-3-1 Catalogue design: Ariana Dibble Photo credits: DJ Hellerman Cover image: Juan Cruz, Manchas, 1986, oil on canvas, 48 x 72 inches, Everson Museum of Art; Gift of Mr. John Dietz, 86.89 Inside front image by Dave Revette. Inside back image by Julie Herman. Everson Museum of Art 401 Harrison Street Syracuse, NY 13202 www.everson.org 2 LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION Honorable Minna R. Buck Stephen and Betty Carpenter The Dorothy and Marshall M. Reisman Foundation The Gifford Foundation Laurence Hoefler Melanie and David Littlejohn Onondaga Community College Neva and Richard Pilgrim Punto de Contacto – Point of Contact Samuel H. Sage Dirk and Carol Sonneborn Martin Yenawine 3 FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Spanning five decades, Juan A. Cruz: A Retrospective presents the work of one of Syracuse’s most beloved artists. Juan Cruz settled in Syracuse in the 1970s and quickly established himself as an important part of the local community. He has designed and painted numerous murals throughout the city, taught hundreds of children and teens how to communicate their ideas through art, and assumed the role of mentor and friend to too many to count. Juan’s art, and very person, are part of the fabric of Syracuse, and it is an honor to be able to share his accomplishments with the world through his exhibition at the Everson Museum of Art. -

Centro Cultural De La Raza Archives CEMA 12

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Online items available Guide to the Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives CEMA 12 Finding aid prepared by Project director Sal Güereña, principle processor Michelle Wilder, assistant processors Susana Castillo and Alexander Hauschild June, 2006. Collection was processed with support from the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS). Updated 2011 by Callie Bowdish and Clarence M. Chan University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 (805) 893-8563 [email protected] © 2006 Guide to the Centro Cultural de la CEMA 12 1 Raza Archives CEMA 12 Title: Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 12 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 83.0 linear feet(153 document boxes, 5 oversize boxes, 13 slide albums, 229 posters, and 975 online items)Online items available Date (inclusive): 1970-1999 Abstract: Slides and other materials relating to the San Diego artists' collective, co-founded in 1970 by Chicano poet Alurista and artist Victor Ochoa. Known as a center of indigenismo (indigenism) during the Aztlán phase of Chicano art in the early 1970s. (CEMA 12). Physical location: All processed material is located in Del Norte and any uncataloged material (silk screens) is stored in map drawers in CEMA. General Physical Description note: (153 document boxes and 5 oversize boxes).Online items available creator: Centro Cultural de la Raza http://content.cdlib.org/search?style=oac-img&sort=title&relation=ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Access Restrictions None. -

REPAIR PHASES of SULEYMANIYE COMPLEX in DAMASCUS Neriman ŞAHİN GÜÇHAN*, Ayşe Esin KULELİ**

REPAIRMETU JFA PHASES 2018/2 OF SULEYMANIYE COMPLEX IN DAMASCUS DOI:METU 10.4305/METU.JFA.2018.2.3 JFA 2018/2 1 (35:2) 1-28 REPAIR PHASES OF SULEYMANIYE COMPLEX IN DAMASCUS Neriman ŞAHİN GÜÇHAN*, Ayşe Esin KULELİ** Received: 09.02.2016; Final Text: 03.11.2017 INTRODUCTION Keywords: Süleymaniye Complex in Damascus; Mimar Sinan; Ottoman; Suleymaniye Complex which was commissioned by Sultan Suleiman the restoration. Magnificent (1495–1566) on the pilgrimage route from Istanbul to Mecca, 1. The first version of this paper was on the bank of the River Barada as the last stop before the desert is one of delivered in the Sinan & His Age Symposium the monuments designed by Mimar Sinan in accordance with the principles but not published. The second version of the study is published as sections of a book of the Ottoman classical period. “Takiyah Suleymaniye” was built between written by the authors and published in 1554 and 1559 on the site that was once occupied by the palace outside 2009. Then this concise and revised version of the article is written in English in 2016 the walls of Damascus commissioned by Memluk ruler Baibars in 1264. It with the addition of some new findings. For is composed of the Mosque, two Tabhanes (hospices), Caravanserais, the more information on evidence, documents Imaret (public soup kitchen), the Madrasa and the Arasta (bazaar) (Kuran, and opinions see: (Şahin Güçhan and Kuleli, 2009). 1986, 69; Necipoğlu, 2005, 222-30) (Figure 1). This paper (1) aims to study the construction and restoration phases of the Complex in chronologically ordered periods by associating the historical documents and researches with the findings and traces in the building (Şahin Güçhan and Kuleli, 2009). -

The Martensz Collection on Sri Lanka at the National Library of Australia

ALRA Newsletter No. 74 (July 2019) A Diplomat’s Gift: the Martensz Collection on Sri Lanka at the National Library of Australia Introduction Today the Martensz Collection is little remembered, though it is described briefly in that invaluable source on the National Library of Australia’s holdings, the Burmester guide (1). Its donation in 1955 was also covered in some detail in the Canberra Times (2). Presentation of the Collection On 2 June 1955 the High Commissioner for Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Mr J. Aubrey Martensz, CBE, presented his personal collection of books about his homeland to the National Library (2). The island nation then called Ceylon is now known as Sri Lanka. For convenience the current name Sri Lanka has been used in this article, except for proper names and in book titles. The gift was formally accepted by the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Mr Archie Cameron, in his role as Chairman of the Library Committee. Those attending the ceremony in the Speaker’s Chambers of Parliament included the Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, the Minister for External Affairs, Richard Casey, and the National Librarian, Harold White. It is hard to imagine a book donation attracting a prime minister and other senior politicians nowadays. Life and career of J. Aubrey Martensz (2)(3) James Aubrey Martensz (1885-1963), was born into a Burgher family in Colombo, the island’s capital. The Burghers, a minority community of mixed Sri Lankan and Western heritage, generally have Portuguese, Dutch, British or other European surnames, the name Martensz being of Dutch origin. -

Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Sculpture

Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Sculpture An exhibition on the centennial of their births MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Speculations in Form Eileen Costello In the summer of 1956, Jackson Pollock was in the final descent of a downward spiral. Depression and alcoholism had tormented him for the greater part of his life, but after a period of relative sobriety, he was drinking heavily again. His famously intolerable behavior when drunk had alienated both friends and colleagues, and his marriage to Lee Krasner had begun to deteriorate. Frustrated with Betty Parsons’s intermittent ability to sell his paintings, he had left her in 1952 for Sidney Janis, believing that Janis would prove a better salesperson. Still, he and Krasner continued to struggle financially. His physical health was also beginning to decline. He had recently survived several drunk- driving accidents, and in June of 1954 he broke his ankle while roughhousing with Willem de Kooning. Eight months later, he broke it again. The fracture was painful and left him immobilized for months. In 1947, with the debut of his classic drip-pour paintings, Pollock had changed the direction of Western painting, and he quickly gained international praise and recog- nition. Four years later, critics expressed great disappointment with his black-and-white series, in which he reintroduced figuration. The work he produced in 1953 was thought to be inconsistent and without focus. For some, it appeared that Pollock had reached a point of physical and creative exhaustion. He painted little between 1954 and ’55, and by the summer of ’56 his artistic productivity had virtually ground to a halt. -

Redalyc.Visiting a Hindu Temple: a Description of a Subjective

Ciencia Ergo Sum ISSN: 1405-0269 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México México Gil-García, J. Ramón; Vasavada, Triparna S. Visiting a Hindu Temple: A Description of a Subjective Experience and Some Preliminary Interpretations Ciencia Ergo Sum, vol. 13, núm. 1, marzo-junio, 2006, pp. 81-89 Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Toluca, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=10413110 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Visiting a Hindu Temple: A Description of a Subjective Experience and Some Preliminary Interpretations J. Ramón Gil-García* y Triparna S. Vasavada** Recepción: 14 de julio de 2005 Aceptación: 8 de septiembre de 2005 * Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, Visitando un Templo Hindú: una descripción de la experiencia subjetiva y algunas University at Albany, Universidad Estatal de interpretaciones preliminares Nueva York. Resumen. Académicos de diferentes disciplinas coinciden en que la cultura es un fenómeno Correo electrónico: [email protected] ** Estudiante del Doctorado en Administración complejo y su comprensión requiere de un análisis detallado. La complejidad inherente al y Políticas Públicas en el Rockefeller College of estudio de patrones culturales y otras estructuras sociales no se deriva de su rareza en la Public Affairs and Policy, University at Albany, sociedad. De hecho, están contenidas y representadas en eventos y artefactos de la vida cotidiana. -

Name: 00000315

Contents Board and Committees, 2003-2004 Volume 15,2003-2004 Photography and reproduction credits: Report of the Chairman and Director Copyright © 2005 by The David and Alfred Front cover, frontispiece, and pages 9,19, 21, 22, Smart Museum of Art, The University of 25, 27, 28, 31, 33-35,37, 39, 41, 43: photography Mission Statement Chicago, 5550 South Greenwood Avenue, by Tom van Eynde. Chicago, Illinois, 60637- All rights reserved. http://smartmuseum.uchicago.edu Pages 47-50, 53-56, 57 (FIGURES 2 and 3), 58-61, ISSN: 1099-2413 65, 67, 69: photography by Jim Newberry. Into Practice: Contemporary Artists and Research Universities Editor: Stephanie Smith Page 57 (FIGURE 1): photography by Katherine Laura Letinsky and Stephanie Smith Publication Assistant: Rachel Furnari Mino. Design: Froeter Design Company, Inc. Printing: Lowitz & Sons, Chicago Page 63: photography by Lloyd de Grane. Acquisitions Frontispiece: © for works by E.L. Kirchner by Ingeborg and Dr. Wolfgang Henze-Ketterer, Wichtrach/Bern. Exhibitions Page 19: courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Publications Page 27: courtesy of Joel-Peter Witkin and Catherine Edelman Gallery. Public Programs Page 30: courtesy ofWalsh Gallery. Contributor and Member Programs Every effort has been made to contact rights holders for all reproductions. Additional rights Sources of Support holders please contact the Smart Museum. Operating Statement Smart Museum Staff 4 Board and Committees, 2003-2004 Report of the Chairman and Director Smart Museum Board of Governors T. Kimball Brooker Marshall J. Padorr Last year was an opportune time to reflect arts. Such programs also provide those outside enterprises took place behind the scenes, as John A. -

Wonder Woman Daughter of Destiny

WONDER WOMAN: DAUGHTER OF DESTINY Story by Jean Paul Fola Nicole, Christopher Johnson and Edmund Birkin Screenplay By Jean Paul Nicole, and Andrew Birkin NUMBERED SCRIPT 1st FIRST DRAFT 1/3/12 I279731 Based On DC Characters WARNER BROS. PICTURES INC. 4000 Warner Boulevard Burbank, California 91522 © 2012 WARNER BROS. ENT. All Rights Reserved ii. Dream Cast Lol. Never gonna happen. Might as well go all in since I'm "straight" black male nerd living in a complete fantasy world writing about Wonder Woman. My cast Diana Wonder Woman - Naomi Scott Ares - Daniel Craig Dr. Poison - Saïd Taghmaoui Clio - Dakota Fanning Mala - Riki Lindhome IO - Regina King Laurie Trevor - Beanie Feldstein Etta Candy - Zosia Mammet Hippolyta - Rebecca Hall Hera - Juliet Binoche Steve Trevor - Rafael Casal Gideon - James Badge Dale Antiope (In screenplay referred to as Artemis) - Nicole Beharie or Jodie Comer Dr. Gogan - Riz Ahmed Alkyone - Jennifer Carpenter or Jodie Comer or Nicole Beharie W O N D E R W O M A N - D A U G H T E R O F D E S T I N Y Out of AN OCEAN OF BLOOD RED a shape emerges. An EAGLE SYMBOL. BECOMING INTENSELY GOLDEN UNTIL ENGULFING THE SCREEN IN LIGHT. CROSS FADE: The beautiful FACE OF A WOMAN with fierce pride (30s). INTO FRAME She is chained by the neck and wrists in a filthy prison cell. DAYLIGHT seeps through prison bars. O.S. Battle gongs echo. Hearing gongs faint echo, her EYES WIDEN. PRISONER They've come for me. This is Queen Hippolyta queen of the Amazons and mother to the Wonder Woman.