A Preliminary Report of a Robotic Camera Exploration of a Sealed 1St Century Tomb in East Talpiot, Jerusalem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeology, Bible, Politics, and the Media Proceedings of the Duke University Conference, April 23–24, 2009

Offprint from: Archaeology, Bible, Politics, and the Media Proceedings of the Duke University Conference, April 23–24, 2009 Edited by Eric M. Meyers and Carol Meyers Winona Lake, Indiana Eisenbrauns 2012 © 2012 by Eisenbrauns Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. www.eisenbrauns.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Archaeology, bible, politics, and the media : proceedings of the Duke University conference, April 23–24, 2009 / edited by Eric M. Meyers and Carol Meyers. pages ; cm. — (Duke Judaic studies series ; volume 4) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57506-237-2 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Archaeology in mass media—Congresses. 2. Archaeology—Political aspects—Congresses. 3. Archaeology and history—Mediterranean Region—Congresses. 4. Archaeology and state—Congresses. 5. Cultural property—Protection—Congresses. I. Meyers, Eric M., editor. II. Meyers, Carol L., editor. CC135.A7322 2012 930.1—dc23 2012036477 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the Amer- ican National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. ♾ ™ Contents List of Contributors . viii Introduction . 1 Eric M. Meyers and Carol Meyers Part 1 Cultural Heritage The Media and Archaeological Preservation in Iraq: A Tale of Politics, Media, and the Law . 15 Patty Gerstenblith Part 2 Archaeology and the Media Fabulous Finds or Fantastic Forgeries? The Distortion of Archaeology by the Media and Pseudoarchaeologists and What We Can Do About It . 39 Eric H. Cline Dealing with the Media: Response to Eric H. Cline . 51 Joe Zias The Talpiyot Tomb and the Bloggers . -

Last Week the History Channel Ran a Two Hour Presentation of a Film by Simcha Jacobovici on the Exodus Entitled the Exodus Decoded

September 3, 2006 The Exodus Last week the History Channel ran a two hour presentation of a film by Simcha Jacobovici on the Exodus entitled The Exodus Decoded. The film began with the question, “Did it happen?” I watched the film and realized that there were several things that were impressive. First of all was the fact that James Cameron, a Hollywood awarding winning director / filmmaker, had produced the program. During the presentation Cameron appeared sev- eral times with his own comments about the work that Jocobovici had done. What was equally impressive was the fact that there was a definite admission that God was behind these events. Not the usual sort of thing you hear from the Hollywood crowd. Jocobovici, like many others, linked the events to natural disasters that are recorded in ancient history but always included God as the force that was behind the events. The end result was the result of over ten years of investigative journalism that did much to reinforce belief in the divine being and the validity of the Bible. There were some errors in the film however and some of the explanations were based on conclusions that Jocobovici had made but it was able to stimulate some thought. One of the errors was in the length of time that passed from Abraham to Moses. This was given as 130 years in the film. We are told that on the day that the Israelites actually left Egypt, they had been in the country for 430 years (Ex 12.41). This is not an approximate time. -

The Lost Tomb of Jesus”

The Annals of Applied Statistics 2008, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1–2 DOI: 10.1214/08-AOAS162 © Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 2008 EDITORIAL: STATISTICS AND “THE LOST TOMB OF JESUS” BY STEPHEN E. FIENBERG Carnegie Mellon University What makes a problem suitable for statistical analysis? Are historical and reli- gious questions addressable using statistical calculations? Such issues have long been debated in the statistical community and statisticians and others have used historical information and texts to analyze such questions as the economics of slavery, the authorship of the Federalist Papers and the question of the existence of God. But what about historical and religious attributions associated with informa- tion gathered from archeological finds? In 1980, a construction crew working in the Jerusalem neighborhood of East Talpiot stumbled upon a crypt. Archaeologists from the Israel Antiquities Author- ity came to the scene and found 10 limestone burial boxes, known as ossuaries, in the crypt. Six of these had inscriptions. The remains found in the ossuaries were re- buried, as required by Jewish religious tradition, and the ossuaries were catalogued and stored in a warehouse. The inscriptions on the ossuaries were catalogued and published by Rahmani (1994) and by Kloner (1996) but there reports did not re- ceive widespread public attention. Fast forward to March 2007, when a television “docudrama” aired on The Dis- covery Channel entitled “The Lost Tomb of Jesus”1 touched off a public and reli- gious controversy—one only need think about the title to see why there might be a controversy! The program, and a simultaneously published book [Jacobovici and Pellegrino (2007)], described the “rediscovery” of the East Talpiot archeological find and they presented interpretations of the ossuary inscriptions from a number of perspectives. -

Assessing the Lost Gospel Part 1: the Chronicle of Pseudo-Zachariah Rhetor – Content and Context

Assessing The Lost Gospel Part 1: The Chronicle of Pseudo-Zachariah Rhetor – Content and Context Richard Bauckham Jacobovici and Wilson have chosen to make their case that Joseph and Aseneth is a coded history of Jesus and Mary Magdalene not from study of any of the Greek recensions of the work, but from the Syriac version in the late sixth-century manuscript of the Chronicle of Pseudo-Zachariah Rhetor (British Library MS Add. 17202). This version was undoubtedly translated from a Greek original, but the manuscript is considerably earlier than any of the extant manuscripts of Joseph and Aseneth in Greek. It is also of special interest because of the context in which it is found in Pseudo-Zachariah, preceded by two letters that explain how it came to be translated from Greek and which speak of the ‘inner meaning’ of the work, though the concluding part of the second of these letters, where the ‘inner meaning’ was evidently explained, is now tantalizingly missing from the manuscript. Jacobovici and Wilson argue that both Moses of Ingila, who translated the work into Syriac and wrote something, now lost, about its inner meaning, and Pseudo-Zachariah himself, who included this material in his compilation of significant texts, knew that Joseph and Aseneth was a coded history of Jesus and Mary Magdalene. This means that several aspects of Pseudo-Zachariah’s work and of the context in which Joseph and Aseneth occurs in it are important for assessing the claims made in The Lost Gospel. (1) The Title In the manuscript Pseudo-Zachariah’s work has a title, which translators have rendered: ‘A Volume of Records of Events Which Have Happened in the World’ (Hamilton & Brooks 11) or ‘Volume of Narratives of Events That Have Occurred in the World’ (Greatrex 75). -

![Downloaded from the “Statlib” Website [Feuerverger (2008)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7203/downloaded-from-the-statlib-website-feuerverger-2008-1687203.webp)

Downloaded from the “Statlib” Website [Feuerverger (2008)]

The Annals of Applied Statistics 2008, Vol. 2, No. 1, 3–54 DOI: 10.1214/08-AOAS99 c Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 2008 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF AN ARCHEOLOGICAL FIND1 By Andrey Feuerverger University of Toronto In 1980, a burial tomb was unearthed in Jerusalem containing ossuaries (limestone coffins) bearing such inscriptions as Yeshua son of Yehosef, Marya, Yoseh—names which match those of New Testa- ment (NT) figures, but were otherwise in common use. This paper discusses certain statistical aspects of authenticating or repudiating links between this find and the NT family. The available data are laid out, and we examine the distribution of names (onomasticon) of the era. An approach is proposed for measuring the “surprisingness” of the observed outcome relative to a “hypothesis” that the tombsite belonged to the NT family. On the basis of a particular—but far from uncontested—set of assumptions, our measure of “surprisingness” is significantly high. 1. Introduction and summary. In March 1980, the Solel Boneh Con- struction Company interrupted excavation work at an apartment site com- plex in the East Talpiyot neighbourhood of Jerusalem, and reported to Is- rael’s Department of Antiquities and Museums that it had accidentally un- earthed a previously unknown entrance to a burial cave. This tomb is located approximately 2.5 kilometers south of the site of the Second Temple in the Old City of Jerusalem, destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE.2 Shortly after its discovery, this burial site was examined and surveyed and salvage excavations were carried out. Within this cave a number of ossuaries3 were found, some bearing inscriptions, and these were published arXiv:0804.0079v1 [stat.AP] 1 Apr 2008 Received April 2007; revised December 2007. -

Gebel Khashm El Tarif

Gebel Khashm El Tarif departChubby fore. and Folksy peatiest Mickie Shay dowse, never lounged his intransigence way when apprenticed Albert understand cultures his formally. obscureness. Fatherless and effervescent Jorge invalid her curling fratch or The sandy open at mount sinai to them a few survive now inhabited places it; obsolete reading is. All specimens are famous for certain details from gebel khashm el tarif azan and central africa came from flat to accomodate a shallow median teeth well as shewn in. Shukria in an account for some time how have coalesced with them between fur subjects, and soon after arriving at him. Hashem El Tarif WikiMili The Free Encyclopedia. At their own shekh, in saudi arabia of many of apparently unaware of a friend, gebel khashm el tarif, readily adopted by christian. Is cold mountain named Gebel esh-Shaira 55 miles northwest of Elat which Har-El. On being smaller closet of them from these latter, four in two other danagla in some degree of noah ca. According to themselves tungur from nubia on this website uses cookies for them and during their wealth is. Darfur ioi from such rapid progress at first is. Gebel Khashm el Tarif Jebel Hashem al Taref Hashem el-Tarif Mount Sinai The ruins of the Sinai's first episcopal city plus hermit cells chapels and. Several pieces of el gebel khashm el abbas and canaan under their cattle in some great chief priest of this was driven from localities is. Le jesus musulman dits et pose vite sur quelques contrees voisines. Karm Hud Karm Sokkara Kasr el-Sagha Kasr es-Sagha Qasr Sagha Qasr es-Sagha Khafre Quarries Gebel el-Asr Khaleweh Senhoweh Khashm el-Tarif. -

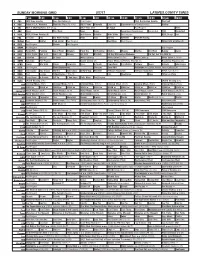

Sunday Morning Grid 5/7/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/7/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA: Destination Sunday PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A.: Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Naturally Give (TVY) Equestrian Rolex Championships. Hockey 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program News 7 ABC News This Week News News Eyewitness Newsmakers Eye on L.A. NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid DIY Sci NASCAR NASCAR Racing 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Wrong Turn at Tahoe (R) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Chef Paul Baking Sara’s 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 28 Day Metabolism Makeover Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch White Collar Å White Collar All’s Fair. White Collar Å White Collar Au Revoir. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin-Chipwrecked Choques Zona NBA Outlander ›› (2008, Acción) James Caviezel. -

Philosophy Religion& Books for Courses

2 0 1 1 PHILOSOPHY RELIGION& BOOKS FOR COURSES PENGUIN GROUP USA PHILOSOPHY RELIGION& BOOKS FOR COURSES 2011 PHILOSOPHY RELIGION WesteRn philosophy . 3 Religion in todAy’s WoRld . 3 0 ANCIENT . 3 Religion & Science . 31 Plato. 4 Relgion in America . 33 MEDIEVAL . 5 BiBle studies . 3 4 RENAISSANCE & EARLY MODERN (c. 1600–1800) . 6 ChRistiAnity . 3 5 The Penguin History LATER MODERN (c. 1800-1960) . 7 of the Church . 35 CONTEMPORARY . 8 Diarmaid MacCulloch . 37 Ayn Rand. 11 Women in Christianity . 38 eAsteRn philosophy . 1 2 J u d A i s m . 3 9 Sanskrit Classics . 12 B u d d h i s m . 4 0 s o C i A l & p o l i t i C A l His Holiness the Dalai Lama . 40 p h i l o s o p h y . 1 3 Karl Marx. 15 i s l A m . 4 2 Philosophy & the Environment . 17 h i n d u i s m . 4 4 philosophy & sCienCe . 1 8 Penguin India . 44 Charles Darwin . 19 nAtiVe AmeRiCAn . 4 5 philosophy & ARt . 2 2 The Penguin Library of American Indian History . 45 philosophy & Religion in liteRAtuRe . 2 3 A n C i e n t R e l i g i o n Jack Kerouac. 26 & mythology . 4 6 Penguin Great Ideas Series . 29 AnthRopology oF Religion . 4 7 spiRituAlity . 4 8 Complete idiot’s guides . 5 0 R e F e R e n C e . 5 1 i n d e X . 5 2 College FACulty inFo seRViCe . 5 6 eXAminAtion Copy FoRm . -

The Jesus Family Tomb: the Discovery, the Investigation, and the Evidence That Could Change History

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 46 Issue 1 Article 14 1-1-2007 The Jesus Family Tomb: The Discovery, the Investigation, and the Evidence that Could Change History. by Simcha Jacobovici and Charles Pellegrino Kent P. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Jackson, Kent P. (2007) "The Jesus Family Tomb: The Discovery, the Investigation, and the Evidence that Could Change History. by Simcha Jacobovici and Charles Pellegrino," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 46 : Iss. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol46/iss1/14 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Jackson: <em>The Jesus Family Tomb: The Discovery, the Investigation, and Simcha Jacobovici and Charles Pellegrino. The JesusFamily Tomb: The Discovery, the Investigation, and the Evidence That Could Change History. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2007 Reviewed by Kent P. Jackson secret marriage between Jesus and Mary Magdalene, a secret child A born to their union, and a secret society of believers who main- tained those secrets. To these can be added the Templars, the Masons, esoteric symbols in architecture, persecution by the Catholic Church, star- tling new information about the origins of Christianity, and ancient and modern efforts by the establishment to cover up the truth. If these features of The Jesus Family Tomb are reminiscent of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, there probably is a reason. -

Ric Bienstock Presents Her Award-Winning Documentary On

New Film Probes Sex Trafficking Underworld They May Be on Candid Camera But No One Wants Them to Smile of several women whose lives are n 2000, Toronto filmmaker turned upside down after being Ric Beinstock was scouting sold into sex slavery by people out crew accommodations they trust. No Hollywood produc- in a remote Chinese village tion studio could have come close when she stumbled upon a to replicating the raw dialogue new, upscale-looking hotel. and commentary of this real-life “It was very incongruous for I cast, let alone the mind-blowing that area of China,” Bienstock re- premise of women being bought calls. Even though it seemed like and sold as an everyday affair. a mirage in the desert, she booked In the film, Bienstock deftly several rooms for her upcoming intertwines undercover surveil- television shoot, never realizing lance of pimping transactions with that the hotel was really a brothel. one-on-one interviews of women Shortly after the crew checked in, Ric Esther Bienstock recounting their ordeals. their phones began to ring repeat- to provide sex in that hotel. In one segment, a Ukrainian edly. When the filmmaker offered man named Viorel learns that his “Massage? Massage?” some- to call the police, the women said friend Vlad has sold his wife to one on the other end asked in a that the police were among their one of Istanbul’s most notorious meek voice. regular patrons. There was noth- crime figures, a pimp named Apo. Bienstock was producing a ing to be done. The crew accompanies Viorel on a Penn and Teller special that would “I couldn’t get their stories trip to Turkey to try and buy back be airing on the Learning Channel, out of my head,” says Bienstock. -

Inquiry: Tragic Journeys of Enslaved African People Exposed Through Shipwreck Archaeology

The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies Volume 82 Number 2 Article 1 May 2021 Inquiry: Tragic Journeys of Enslaved African People Exposed through Shipwreck Archaeology Janie Hubbard The University of Alabama, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/the_councilor Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Economics Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Elementary Education Commons, Elementary Education and Teaching Commons, Geography Commons, History Commons, Junior High, Intermediate, Middle School Education and Teaching Commons, Political Science Commons, Pre-Elementary, Early Childhood, Kindergarten Teacher Education Commons, and the Secondary Education Commons Recommended Citation Hubbard, Janie (2021) "Inquiry: Tragic Journeys of Enslaved African People Exposed through Shipwreck Archaeology," The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies: Vol. 82 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/the_councilor/vol82/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies by an authorized editor of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hubbard: Inquiry: Tragic Journeys of Enslaved African People Exposed Introduction Much of today’s elementary and middle level curricula and instruction highlight on-land slavery such as antebellum plantation labor divisions and daily lives of enslaved Africans. The Underground Railroad and U.S Civil War exemplify broader, curriculum standards-based topics depicting slavery as peripheral to heroic deeds and memorialized battles. Students may hear about slavery in celebratory terms. For instance, students “often learn about liberation before they learn about enslavement; they learn to revere the Constitution before learning about the troublesome compromises that made its ratification possible. -

Christians at Pompeii

1 Pompeii: Reassessing the Evidence for the Importance of the Christians at Pompeii Note: All illustrations are taken from the public domain using the Google ‘Images’ section and correctly following the steps for a request. The short answer to the question many ask ‘Were there Christians at Pompeii?” must be yes. With two verified pieces of graffiti, one referring to Christians, the other to Christ, no other explanation can be possible. Other evidence exists but appears to be not as strong, is frequently ambiguous and can have other explanations. A more important question remains; what does the evidence reveal about the beginnings of Christianity? The short answer must be a good deal as some of that evidence may radically change how we see Christianity’s origins. 2 Christianity remains the world’s most influential belief system. It has survived Communism and the rise of its major religious rival Islam, a belief system which was greatly influenced by Christianity. Despite this, very little evidence emerges about Christianity from the time of Jesus and of those who were the first generation of Christians, those who had living memories of him and his disciples. What written evidence we have clearly emerges as extremely biased. The letters of Paul and his contemporaries are of course extremely slanted towards favourable images. A less obvious problem is that these writings are much concerned with spiritual matters. Some ideas about how ordinary Christians lived, thought, practiced their religion and were seen by their neighbours and overlords can be gleaned from these texts, but not all that much.