An Analysis of Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Minnesang, Although in the English Language, to Allow It to Be Judged in This Kingdom A&S Competition

I follow her banner Unlike a helpless sparrow that is the swift hawk’s prey Just like a hunter’s arrow once aimed will kill the jay So she will be my destiny to conquer her my finest deed She forced me almost to retreat with beauty, grace and chastity My life was vain and hollow and frequently I went astray No better banner I can follow than hers, wherever is the way. Is she at least aware of me? from places far away I heed I am a grain in fields of wheat a drop of water in the sea. I suffer from a dreadful sorrow how often did I quietly pray That there will be no more tomorrow so that my pain shall go away. My bended neck just feels her knee crouched in the dust beneath her feet Deliverance, which I so dearly need she never will award to me. 1 Nîht ein baner ich bezzer volgen mac Middle-High German version Niht swie diu spaz sô klein waz ist der snel valken bejac alsô swie der bogenzein ûf den edel valken zil mac sô si wirt sîn mîne schône minne ir eroberigen daz ist mîne bürde mîne torheit wart gevalle vor ir burc aber dur ir tugenden unde staetem sinne Was sô verdriezlich mîne welte verloufen vome wege manige tac mîne sunnenschîn unde schône helde nîht ein baner ich bezzer volgen mac ûzem vremde lant kumt der gruoze mîn wie sol si mich erkennen enmitten vome kornat blôz ein halm enmitten vome mer ein kleine tröpfelîn Ich bin volleclîche gar von sorgen swie oft mac ich wol mahtlôs sinnen daz ie niemer ist ein anders morgen alsô mîne endelôs riuwe gât von hinnen der nûwe vrôdenreich wol doln ir knie in drec die stolzecheit kumt ze ligen die gunst diu ich sô tuon beger mîner armen minne gift si nimmer nie 2 Summary Name: Falko von der Weser Group: An Dun Theine This entry is a poem I wrote in the style of the high medieval German Minnelieder (Minnesongs) like those found in the “Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift”, also known as Codex Manesse (The Great Heidelberg Songbook) and the “Weingartner Liederhandschrift” (The Konstanz-Weingarten Songbook). -

Three Songs of Reinmar Der Alee a Formal-Structural Interpretation

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly ss received 66-1860 WEDGWOOD, Stephen H ensleigh, 1936- THREE SONGS OF REINMAR DER ALTE: A FORMAL-STRUCTURAL INTERPRETATION. The Ohio State University, Fh.D., 1965 Language and Literature, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THREE SONGS OF REINMAR DER ALEE A FORMAL-STRUCTURAL INTERPRETATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Hensleigh Wedgwood, A.B., M.A. The Ohio State University 1965 Approved by v Adviser, Department of German PREFACE The modern interpreter of medieval literature faces certain difficulties which are, by the nature of things, insurmountable. The most serious from a practi cal viewpoint is perhaps the lack of reliable texts. The manuscripts which transmit Reinmar's songs, for example, date at the earliest from the end of the thirteenth cen tury — nearly a century after the death of the poet. During the several generations which separate the songs' composition from their collection and copying in the various manuscripts, numerous corruptions, omissions, and rearrangements necessarily occurred which, despite the best efforts of distinguished textual scholars since Karl Lachmann and before, simply cannot be rectified. The critic, seeking to approach and understand Reinmar and the other Minnesingers, deals at best with an approxima tion of what the poet actually sang. In yet another sense our understanding of Rein- mar's songs can only be approximate. Reinmar, like his contemporaries, was as much composer as poet. Words and music of the Minnesanp; were created together, each song in its own characteristic "Ton," and undoubtedly the musi cal structure of the songs in large part determined their verbal form. -

Lyrik Hat Vorbildfunktion Für Die Minnelyrik)

Schulbuch online für Deutsch Vorwort zu den Kurzfassungen der Literatur-Epochen nach Stichwort Literatur (© VERITAS Verlag, Linz) Liebe Kolleginnen und Kollegen, Zweck der vorliegenden Kurzfassungen – basierend auf Stichwort Literatur. Geschichte der deutschsprachigen Literatur – ist es, Ihnen einen schnellen und effizienten Überblick über alle Epochen der deutschsprachigen Literatur zur Verfügung zu stellen. Nicht zu vermeiden ist durch die (gewollte) Reduzierung auf ein „Skelett“ eine natürlich verkürzte Sichtweise, die eine intensive Auseinandersetzung und Beschäftigung mit der Literatur der einzelnen Epochen keinesfalls ersetzen kann. Aus diesem Grund liegt es selbstverständlich in Ihrer Verantwortung als Lehrerin / Lehrer, ob Sie die Kurzfassungen in dieser Form an Ihre Schülerinnen und Schüler weitergeben möchte. Diese Internetseite ist deshalb auch nur Lehrerinnen und Lehrern mit Passwort zugänglich. Eva und Gerald Rainer Norbert Kern Verzeichnis der Epochen - Mittelalter (750–1450) - Renaissance – Humanismus – Reformation (1470–1600) - Literatur des Barock (17. Jahrhundert) - Das Jahrhundert der Aufklärung (18. Jahrhundert) - Sturm und Drang (1770–1785) - Klassik (1786–1805) - Abseits der literarischen Strömungen: Heinrich von Kleist und Friedrich Hölderlin - Romantik (1795–1830) - Biedermeier und Vormärz – Literatur zwischen 1815 und 1848 - Bürgerlicher Realismus (1848–1885) - Naturalismus (1880–1900) - Gegenströmungen zum Naturalismus (1890–1920) - Expressionismus (1910–1920) - Bürgerliche Literatur vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg - Die Literatur der Weimarer Republik (1918–1933) - Österreichische Literatur zwischen 1918 und 1938 - Literatur im deutschen Faschismus 1933–1945 - Literatur des Exils - Literatur in der BRD nach 1945 - Literatur in der ehemaligen DDR - Die deutschsprachige Literatur der Schweiz - Österreichische Literatur nach 1945 Schulbuch online für Deutsch Mittelalter (750-1450) Frühes Mittelalter (750–1170) Grundzüge Es gibt kaum deutschsprachige Literatur, der Großteil der Literatur ist in lateinischer Sprache verfasst. -

Gottfried Von Strassburg - a German Humanist of the Twelfth Century Par Excellence

Gottfried von Strassburg - A German Humanist of the Twelfth Century Par Excellence Albrecht Classen University of Arizona [email protected] https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/futhark.2012.i07.04 Abstract: Normally we identify the so-called Renaissance of the twelfth centuty with theologians, philosophers, and artists. But many poets from the turn of the century (1200) have made major intellectual contributions to this Renaissance as well. Especially Gottfried von Strassburg’s Tristan can be regarded as an extraordinary literary accomplishment characterized by its fascinating combination of fictional elements with those of a philosophical origin. The purpose of this article is to recognize the central message of Tristan as not being limited to the theme of love, but, emerging from the discourse of love, as a critical engagement with basic question pertaining to human existence. Keywords: Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, Gottfried von Strassburg, Tristan, love discourse, medieval philosophy and theology When Charles Homer Haskins coined the phrase ‘Renaissance of the twelfth century’, he had put his finger on a monumental intellectual-cultural movement that certainly deserves such a glamorous epithet, even though we have learned to differentiate considerably this optimistic evaluation of that period since then1. Major cathedrals, castles, and other monuments were erected during that Gothic period, which we do not need to define too narrowly as limited precisely to the years between 1100 and 1200. Universities sprang up all over Europe, and the secular courts also developed extensively, providing a new forum for the arts, literature, and music, not to mention the growth of cities, international trade, and the sciences2. -

Die Minnesänger in Bayern Und Österreich Richard Bletschacher

Richard Bletschacher hat von den zahlreichen Minnesängern aus dem bayrisch-österreichischen Raum die bekanntesten sowie bestdokumen- tierten ausgewählt. Sie werden mit ihrer Biographie als auch einer Aus- wahl ihrer Werke, die vom Autor neu übersetzt wurden, vorgestellt. Zu den im Buch versammelten zählen: Der von Kürenberg, Dietmar von Aist, der Burggraf von Regensburg, der Burggraf von Rietenburg, Albrecht von Johansdorf, Walther von der Vogelweide, Wolfram von Eschenbach, der Markgraf von Hohenburg, Neidhart von Reuental, der Tannhäuser, der von Suoneck, Hiltbold von Schwangau, Ulrich von Liechtenstein, Ulrich von Sachsendorf, der Hardegger, Reinmar von Brennenberg, Leuthold von Seven, Alram von Gresten, Gunther von dem Forste, der Litschauer, Heinrich von der Muore, der Mönch von Salzburg, Hugo von Montfort und Oswald von Wolkenstein. Das zeitliche Spektrum reicht von frühen Vertretern (ab Mitte des 12. Jahr- hunderts) im Hochmittelalter bis zum letzten Nachfolger Oswald von Wolkenstein (1376–1445). Richard Bletschacher, geboren 1936, ist Regisseur, Dramaturg, Maler und Autor zahlreicher Operntexte, Schauspiele, Erzählungen, musik- wissenschaftlicher Studien. Er war von 1982 bis 1996 an der Wiener Staatsoper als Chefdramaturg tätig. Er lebt und arbeitet in Wien und Drosendorf an der Thaya (NÖ). Die MinnesängerDie in und Bayern Österreich Richard Bletschacher Die Minnesänger in Bayern und Österreich Richard Bletschacher Die Minnesänger COVER.indd 1 19.2.2016 14:54:08 DIE MINNESÄNGER IN BAYERN UND ÖSTERREICH Bletschacher-Minnesang.indd 1 19.02.2016 10:54:29 Bletschacher-Minnesang.indd 2 19.02.2016 10:54:29 Richard Bletschacher DIE MINNESÄNGER IN BAYERN UND ÖSTERREICH Bletschacher-Minnesang.indd 3 19.02.2016 10:54:29 Lektorat und Layout: Johann Lehner (Wien, Österreich) Korrektorat: Katharina Preindl (Wien, Österreich) Cover: Nikola Stevanović (Belgrad, Serbien) Druck und Bindung: Interpress (Budapest, Ungarn) Umschlagbild: Ausschnitt aus „Herr Alram von Gresten: Minnegespräch“ Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift (Codex Manesse), Universität Heidelberg, Cod. -

Dichtung Aus Österreich

© 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May be used for personal purporses only or by libraries associated to dandelon.com network. DICHTUNG AUS ÖSTERREICH VERSEPIK UND LYRIK 2. TEILBAND: LYRIK Herausgegeben von: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Eugen Thurnher Gesamtredaktion: Dr. Elisabeth Schmitz-Mayr-Harting ÖSTERREICHISCHER BUNDESVERLAG FÜR UNTERRICHT, WISSENSCHAFT UND KUNST WIEN INHALTSVERZEICHNIS DES TEILBANDES LYRIK VERZEICHNIS DER ABBILDUNGEN 30* VORWORT Von Dr. Hermann Lein 31* EINFÜHRUNG Von Eugen Thurnher 35* SINGEN UND SAGEN IM DONAULAND UND IM GEBIRGE 1. Gotteslob und Frauenminne Mariensequenz aus St. Lambrecht 3 Das Melker Marienlied 4 Der von Kürenberg Wes manest du mich leides, min vil liebez liep? 5 Leit machet sorge vil liebe wünne 6 Ich zoch mir einen valken mere danne ein jar 6 Ez gät mir vonme herzen daz ich geweine 6 Der tunkele sterne sam der birget sich 7 Dietmar von Aist Ahi nu kumet uns diu zit, der kleinen vogelline sanc 7 Waz ist für daz trüren guot, daz wip nach lieben manne hat? 8 Seneder friundinne böte, nu sage dem schcenen wibe 8 Uf der linden obene da sanc ein kleinez vogellm 9 Ez stuont ein frouwe alleine 9 So wol dir, sumerwunne! 9 Sich hat verwandelot diu zit 10 Släfst du, friedel ziere? 10 Urlop hat des sumers brehen 11 Wart äne wandel ie kein wip 11 Hartwig von Raute Mir tuot ein sorge we in minem muote 12 Ich bin gebunden zallen stunden 12 Reinmar von Hagenau Ein liep ich mir vil nähe trage 13 Ich wirde jämmerlichen alt 14 Ich lebte ie nach der Hute sage 14 Wiest ime ze muote, wundert mich 15 Ich wasn mir liebe geschehen wil 15 Ich wirbe umb allez daz ein man 16 Ein wJser man sol niht ze vil 16 Niemen seneder suoche an mich deheinen rät 18 Sage, daz ich dirs iemer lone 18 Des tages do ich daz kriuze nam 19 Däst ein not daz mich ein man 19 6* Inhaltsverzeichnis 2. -

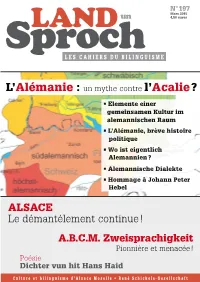

Alsace Le Démantèlement Continue! A.B.C.M

n°197 mars 2015 un 4,50 euros SprochLand les cahiers du bilinguisme L’Alémanie : un mythe contre l’Acalie ? • Elemente einer gemeinsamen Kultur im alemannischen Raum • L’Alémanie, brève histoire politique • Wo ist eigentlich Alemannien ? • Alemannische Dialekte • Hommage à Johann Peter Hebel alsace Le démantèlement continue! a.b.c.m. Zweisprachigkeit Pionnière et menacée! Poésie dichter vun hit hans haid un c ulture et bilinguisme d’ a l s a c e m o s e l l e • r e n é s c h i c k e l e - g esellschaftSprochLand 1 é d i t o r i a l s o m m a i r e l’europe reste editorial p. 2 notre horizon les deux votes régionalistes p. 3-4 e vent antieuropéen souffle de plus en plus fort. Qu’il ait alsace : poursuite du démantèlement p. 4-5 un succès croissant dans la l a.b.c.m. Zweisprachigkeit - 25 ans après ! p. 6-9 presse populiste anglo-saxonne, auprès de la nouvelle frénésie nationaliste polonaise ou dans les mouvements jacobins français ne l’alémanie : un mythe surprend pas. contre l’acalie ? p. 10 - 21 Il est plus inquiétant de voir que même en Alsace cet esprit délétère se fait de plus en • Eine vergessene Einheit? p. 11-13 plus sentir, y compris chez des militants de la cause • Brève histoire politique p. 14-15 alsacienne. Un sophisme se développe chez certains : • Wo ist eigentlich Alemannien? p. 16 «je suis pour l’Europe, mais contre l’Union européenne». Soyons sérieux : il n’y a qu’une seule Europe et elle • Alemannische Dialekte p. -

Allerlei, Florilège De Littérature Alsacienne

LIVRE DE L’ÉLÈVE 17 cahier numéro : Coordination Jean-Claude Graeff Jean-Claude Schwendemann Florilège de littérature alsacienne ALLERLEI Langue et Culture Régionales Florilège de littérature alsacienne ALLERLEI Langue et Culture Régionales 17 LIVRE DE L’ÉLÈVE Coordination : Jean-Claude Graeff Jean-Claude Schwendemann cahier numéro Nos remerciements à : Monsieur Alain Domenech, Inspecteur Pédagogique Régional, Inspecteur d’Académie • Arts plastiques • Strasbourg & Madame Pascale Mathieu, Professeur d’Arts plastiques, Collège Rouget de Lisle de Schiltigheim pour l’illustration de couverture Académie de Strasbourg Mission Académique aux Enseignements Régionaux et Internationaux 6 rue de la Toussaint • 67975 Strasbourg Cedex 9 Téléphone 03 88 23 37 23 • Télécopie 03 88 23 39 99 CRDP d’Alsace 23 rue du Maréchal Juin • BP 279 / R7 • 67007 Strasbourg Cedex Téléphone 03 88 45 51 60 • Télécopie 03 88 45 51 79 Réédition numérique : décembre 2010 ISSN : 0763-8604 ISBN 1998 : 2-86636-236-5 ISBN 2010 : 978-2-86636-402-1 Avant-propos : page 3 Il est indéniable qu’Otfried de Wissembourg fut au IX e siècle le premier poète de langue allemande, de même que nul ne contestera la place de Claude Vigée dans la littérature française. Mais dans quelle littérature classer des auteurs qui comme André Weckmann ou Conrad Winter s’expriment tout aussi bien dans la langue de Molière que dans celle de Goethe ou dans le dialecte de leur village natal ? De telles considérations posent le problème de la définition de la littérature en général et de la littérature alsacienne en particulier. Mais le propos de cet ouvrage n’est pas de se demander s’il existe une littéra- ture alsacienne ou simplement une littérature en Alsace. -

Maturitätsprüfungen ISME Deutsch · Literaturauswahl

Deutsch · Schmid Literaturauswahl Maturitätsprüfungen Maturitätsprüfungen ISME Deutsch · Literaturauswahl Die kursiven Zahlen geben die (für die Leselisten anzurechnenden) Leseseiten an, nicht die Seitenzahlen der Buchausgaben. Abkürzungen: es Edition Suhrkamp rub Reclams Universalbibliothek bs Bibliothek Suhrkamp it Insel Taschenbuch st Suhrkamp Taschenbuch detebe Diogenes Taschenbuch kiwi Kiepenheuer & Witsch Taschenbuch stw Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Wissenschaft dtv Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag rororo Rowohlts Rotationstaschenbücher ub Ullstein Taschenbuch Epik — Essay / Theorie Dramatik Lyrik Epoche A: bis Klassik Antike Sophokles: Antigone (442 v. Chr.) [rub 659: 56] — König Ödipus (427 v. Chr.) [rub 630: 66] Euripides: Medea (431 v. Chr.) [rub 849: 42] Mittelalter Minnesang Auswahl (1150-1300) [rub Hartmann von Aue: Gregorius (1190) [rub 1787: 115] 7857]: — Der arme Heinrich (1195) [rub 456: 44] Kürenberger, Heinrich von Veldeke, Nibelungenlied (1200) [Klett; Hg. Fühmann: 150] Dietmar von Eist, Hartmann von Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival (1200/10) [ub 23908: 414; Aue, Reinmar von Hagenau, Heinrich gekürzt: rub 7451: 72] von Morungen Gottfried von Strassburg: Tristan und Isolde (1210) [Nachdich- Walther von der Vogelweide tung Günter de Bruyn: fischer 8275: 109] Spätmittelalter/ Humanismus/ Renaissance William Shakespeare: Romeo und Julia (1597) [rub Oswald von Wolkenstein (1400/40) Wernher der Gärtner: Helmbrecht (1250/80) [rub 1188: ca. 60] 5: 95] Johannes von Tepl: Der Ackermann und der Tod (1401) [rub —Hamlet, Prinz von Dänemark (1600) [rub 31: 120] 7666: 36] — Macbeth (1605) [rub 17: 72] Martin Luther: *Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen (1530) [rub 1578: 23] — König Lear (1606) [rub 13: ca. 100] ISME (Sd) · Jan 2003 (2.1) 1 Deutsch · Schmid Maturitätsprüfungen · Literaturauswahl Barock Jacob Bidermann: Cenodoxus (1635) [rub 8958: ca. Andreas Gryphius (1637/50) [rub 8799] Hans J. -

Dissertation Draft April 2014 Post

! ! ! ! ! ! A Law unto Himself: Tristanian Jurisprudence in Gottfried’s Tristan ! ! ! Noah Dylan Goldblatt ! Virginia Beach, Virginia ! ! Bachelor of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2007 Master of Arts, University! of Virginia, 2009 ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of ! Doctor of Philosophy ! ! Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures ! University of Virginia May, 2014 !i ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! © Copyright by Noah Dylan Goldblatt All Rights Reserved May 2014 ! !ii Abstract ! This dissertation analyzes literary jurisprudence in Gottfried’s Tristan and explicates the poem as an exemplar of Grimm’s theory of medieval law-poetry. This study examines how Gottfried dramatizes the institutions and practices of law, such as feudal tenure, judicial combat, and evidentiary debate. Chapter One traces the history of Gottfried’s Tristan as an object of study for law-in-literature research. The chapter also analyzes the poet’s relationship to and distinction from the Arthurian tradition. Chapter Two investigates legal discourse relating to the intersection of geography and authority in the poem. The chapter explicates scenes related to property transmission and contractual obligations. Chapter Three examines the juridical language and logical structures of judicial duels in the cases of Morgan and Morold. Chapter Four discusses the scrutiny of direct and indirect evidence in three scenes: The Seneschal and the Dragon Tongue, Isolde and the Sword Splinter, and the Flour on the Floor. The fourth chapter also elucidates the manner in which Tristan and Isolde rhetorically manipulate the presentation of evidence in order to deceive King Mark and his surrogates, Marjodoc and Melot. -

Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend With Texts and Translations of his Works j. w. thomas UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 77 Copyright © 1974 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Thomas, J. W.Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend: With Texts and Translations of his Works. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1974. doi: https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469658483_ Thomas Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Thomas, John Wesley. Title: Tannhäuser : poet and legend / by John Wesley Thomas. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 77. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1974] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 73-15986 | isbn 978-1-4696-5847-6 (pbk: alk. -

Medieval German Lyric Verse in English Translation COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Medieval German Lyric Verse in English Translation COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Medieval German Lyric Verse in English Translation j. w. thomas UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 60 Copyright © 1968 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Thomas, J. W.Medieval German Lyric Verse in English Translation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968. doi: https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469658506_Thomas Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Thomas, J. W. Title: Medieval German lyric verse in English translation / by J. W. Thomas. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 60. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1968] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 68064911 | isbn 978-1-4696-5849-0 (pbk: alk.