Algeria–Mali Trade: the Normality of Informality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20131217 Mli Reference Map.Pdf

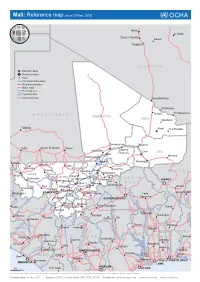

Mali: Reference map (as of 29 Nov. 2013) AdrarP! !In Salah Zaouiet Kounta ! Aoulef ! ! Reggane ALGERIA National capital Regional capital Town International boundary ! Regional boundary Major road Perennial river Perennial lake Intermittent lake Bordj Mokhtar ! !Timiaouine ! Tin Zaouaten Tessalit ! MAURITANIA TOMBOUCTOU KIDAL Abeïbara ! Tidjikdja ! Kidal Ti-n-Essako P! ! Tombouctou Bourem ! Ayoun El Atrous ! Kiffa ! Néma P! ! ! Goundam Gourma- ! Gao GAO !Diré Rharous P! Ménaka Niafounké ! ! ! Youwarou Ansongo ! Sélibaby ! ! ! Nioro ! MOPTI Nara Niger ! Sénégal Yélimané SEGOU Mopti Douentza !Diéma Tenenkou ! P! NIGER SENEGAL P! Bandiagara KAYES ! Kayes ! Koro KOULIKORO Niono Djenné ! ! ! ! BURKINA !Bafoulabé Ké-Macina Bankass NIAMEY KolokaniBanamba ! ! P!Ségou ! FASO \! Bani! Tominian Kita ! Ouahigouya Dosso ! Barouéli! San ! Keniéba ! ! Baoulé Kati P! Nakanbé (White Volta) ! Koulikoro Bla ! \! Birnin Kebbi Kédougou BAMAKO ! KoutialaYorosso Fada Niger ! Dioila ! ! \! Ngourma Sokoto Kangaba ! ! SIKASSO OUAGADOUGOU Bafing Bougouni Gambia ! Sikasso ! P! Bobo-Dioulasso Kandi ! ! Mouhoun (Black Volta) Labé Kolondieba! ! GUINEA Yanfolila Oti Kadiolo ! ! ! Dapango Baoulé Natitingou ! Mamou ! Banfora ! ! Kankan Wa !Faranah Gaoua ! Bagoé Niger ! Tamale Rokel ! OuéméParakou ! ! SIERRA Odienné Korhogo Sokodé ! LEONE CÔTE GHANA BENIN NIGERIA Voinjama ! TOGO Ilorin ! Kailahun! D’IVOIRE Seguela Bondoukou Savalou ! Komoé ! ! Nzérékoré ! Bouaké Ogun Kenema ! ! Atakpamé Man ! ! Sunyani ! ! Bandama ! Abomey ! St. PaulSanniquellie YAMOUSSOKRO Ibadan Kumasi !\ ! Ho Ikeja ! LIBERIA Guiglo ! ! Bomi ! Volta !\! \! Gagnoa Koforidua Buchanan Sassandra ! ! \! Cotonou PORTO NOVO MONROVIA ! LOMÉ Cess ABIDJAN \! 100 Fish Town ACCRA ! !\ Km ! The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Creation date: 29 Nov. 2013 Sources: UNCS, Natural Earth, ESRI, NGA, OCHA. Feedback: [email protected] www.unocha.org www.reliefweb.int. -

Algeria–Mali Trade: the Normality of Informality

101137 DEMOCRACY Public Disclosure Authorized AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ERF 21st ANNUAL CONFERENCE March 20-22, 2015 | Gammarth, Tunisia 2015 Public Disclosure Authorized Algeria–Mali Trade: The Normality of Informality Sami Bensassi, Anne Brockmeyer, Public Disclosure Authorized Matthieu Pellerin and Gael Raballand Public Disclosure Authorized Algeria–Mali Trade: The Normality of Informality Sami Bensassi Anne Brockmeyer Mathieu Pellerin Gaël Raballand1 Abstract This paper estimates the volume of informal trade between Algeria and Mali and analyzes its determinants and mechanisms, using a multi-pronged methodology. First, we discuss how subsidy policies and the legal framework create incentives for informal trade across the Sahara. Second, we provide evidence of the importance of informal trade, drawing on satellite images and surveys with informal traders in Mali and Algeria. We estimate that the weekly turnover of informal trade fell from approximately US$ 2 million in 2011 to US$ 0.74 million in 2014, but continues to play a crucial role in the economies of northern Mali and southern Algeria. Profit margins of 20-30% on informal trade contribute to explaining the relative prosperity of northern Mali. We also show that official trade statistics are meaningless in this context, as they capture less than 3% of total trade. Finally, we provide qualitative evidence on informal trade actors and mechanisms for the most frequently traded products. JEL classification codes: F14, H26, J46. Keywords: informal trade, Algeria, Mali, fuel, customs. 1 The authors would like to thank Mehdi Benyagoub for his help on this study, Laurent Layrol for his work on satellite images, Nancy Benjamin and Olivier Walther for their comments and Sabra Ledent for editing. -

Algerian Military

Algerian Military Revision date: 5 April 2021 © 2010-2021 © Ary Boender & Utility DXers Forum - UDXF www.udxf.nl Email: [email protected] Country name: Al Jumhuriyah al Jaza'iriyah ad Dimuqratiyah ash Sha'biyah (People's Democratic Republic of Algeria) Short name: Al Jaza'ir (Algeria) Capital: Algiers 48 Provinces: Adrar, Ain Defla, Ain Temouchent, Alger, Annaba, Batna, Bechar, Bejaia, Biskra, Blida, Bordj Bou Arreridj, Bouira, Boumerdes, Chlef, Constantine, Djelfa, El Bayadh, El Oued, El Tarf, Ghardaia, Guelma, Illizi, Jijel, Khenchela, Laghouat, Mascara, Medea, Mila, Mostaganem, M'Sila, Naama, Oran, Ouargla, Oum el Bouaghi, Relizane, Saida, Setif, Sidi Bel Abbes, Skikda, Souk Ahras, Tamanrasset, Tebessa, Tiaret, Tindouf, Tipaza, Tissemsilt, Tizi Ouzou, Tlemcen Military branches: People's National Army (Aljysẖ Alwṭny Alsẖʿby) Navy of the Republic of Algeria (Alqwạt Albḥryẗ Aljzạỷryẗ) Air Force (Al-Quwwat al-Jawwiya al-Jaza'eriya) Territorial Air Defense Force (Quwwat Aldifae Aljawiyi ean Al'iiqlim) Gendarmerie Nationale (Ad-Darak al-Watani) Republican Guard (Alharas Aljumhuriu Aljazayiriu) Notes: - The Algerian Military are using a large amount of frequencies on HF and new frequencies are added all the time. Hence, this list is not complete. - Additions or corrections are greatly appreciated. Please mail them to [email protected] Nationwide and Regional Commands ALE idents: CFT Commandement des Forces Terrestre, Aïn-Naâdja CM1 Commandement de la 1e région militaire, Blida CM2 Commandement de la 2e région militaire, Oran CM3 Commandement de la -

Water Scarcity, Security and Democracy

Water Scarcity, Security and democracy: a mediterranean moSaic © 2014 by Global Water Partnership Mediterranean, Cornell University and the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future. All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in Athens, Greece, and Ithaca, NY. ISBN 978-1-4951-1550-9 The opinions expressed in the articles in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Global Water Partnership Mediterranean or Cornell University’s David R. Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future. Layout and cover design: Ghazal Lababidi Water Scarcity, Security and democracy: a mediterranean moSaic EditEd by FrancEsca dE châtEl, Gail holst-WarhaFt and tammo stEEnhuis TABLE OF CONTENTS foreWord 6 introduction 8 i. tHe neW culture of Water 16 1. Glimpses of a New Water Civilization 18 2. Water Archives, a History of Sources: The Example of the Hérault in France’s Langueoc-Roussillon Region 32 3. Meander(ing) Multiplicity 36 4. A Spanish Water Scenario 46 5. Transboundary Management of the Hebron/Besor Watershed in Israel and the Palestinian Authority 52 6. The Drin Coordinated Action Towards an Integrated Transboundary Water Resources Management 62 7. The Times They Are A-Changin’: Water Activism and Changing Public Policy 72 8. Water Preservation Perspectives as Primary Biopolicy Targets 82 ii. coping WitH SCARCITY 84 9. Leaving the Land: The Impact of Long-term Water Mismanagement in Syria 86 10. Desert Aquifers and the Mediterranean Sea: Water Scarcity, Security, and Migration 98 11. The Preservation of Foggaras in Algeria’s Adrar Province 108 12. The Need for a Paradigm Change: Agriculture in the Water-Scarce MENA Region 114 13. -

Memoire Le Diplôme De Master Professionnel

N° d’ordre : 06/DSTU/2016 MEMOIRE Présenté à L’UNIVERSITE ABOU BEKR BELKAID-TLEMCEN FACULTE DES SCIENCES DE LA NATURE ET DE LA VIE ET SCIENCES DE LA TERRE ET DE L’UNIVERS DEPARTEMENT DES SCIENCES DE LA TERRE ET DE L’UNIVERS Pour obtenir LE DIPLÔME DE MASTER PROFESSIONNEL Spécialité Géo-Ressources par Meriem FETHI APPORT DE LA GEOLOGIE DAND L’EXPLOITATION DES GISEMENT DE GRANULATS (CAS D’UNE CARRIERE DANS LA REGION D’ADRAR) Soutenu le 30 juin 2016 devant les membres du jury : Mustapha Kamel TALEB, MA (A), Univ. Tlemcen Président Hassina LOUHA, MA (A), Univ. Tlemcen Encadreur Souhila GAOUAR, MA (A), Univ. Tlemcen Examinateur Fatiha HADJI, MA (A), Univ. Tlemcen Examinateur TABLE DES MATIERES Dédicace Remerciement Résumé Abstract BUT ET ORGANISATION DE TRAVAIL A. But de travail ........................................................................................................ 1 B. Méthodologie ....................................................................................................... 1 Chapitre I INTRODUCTION GENERAL I. SITUATION GEOGRAPHIQUE DE LA WILAYA D’ADRAR ........... 2 II. GEOMORPHOLOGIE, HYDROGRAPHIE, CLIMAT ET VEGETATION :.. ........................................................................................ 3 II.1. Géomorphologie : ........................................................................................ 3 II.2. Ressource hydrogéologiques : ..................................................................... 4 II.3. Climatologie et végétation : ........................................................................ -

Mémoire De Master En Sciences Économiques Spécialité : Management Territoriale Et Ingénierie De Projet Option : Économie Sociale Et Solidaire

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE Université Mouloud Mammeri Tizi Ouzou Faculté des sciences économiques commerciales et des sciences de gestion Département des sciences économiques Laboratoire REDYL Mémoire De master en sciences économiques Spécialité : management territoriale et ingénierie de projet Option : économie sociale et solidaire Caractérisation de la gestion de l’eau en tant que bien communs dans l’espace saharien Algérien mode de gouvernance du système traditionnel des foggaras Présenté par : Sous-direction : GHAOUI Nawal Pr. AHMED ZAID Malika HADJALI Sara Année universitaire : 2016/2017 Caractérisation de la gestion de l’eau en tant que bien communs dans l’espace saharien Algérien mode de gouvernance du système traditionnel des foggaras Résumé du mémoire : Depuis quelques années, la ressource en eau n’est plus seulement appréhendée en termes de disponibilité et d’usage mais aussi comme un bien commun à transmettre aux générations futures .Ces deux conceptions de l’eau demeurent grandement contradictoire malgré les efforts déployés pour concilier viabilité économique et participation sociale. Dans ce contexte, au Sahara algérien le système traditionnel d’irrigation « foggara » constitue un élément majeur pour comprendre la complexité de la relation entre les ressources en eau disponibles, la gestion et la gouvernance de la ressource, son usage et la prise de décision. Mots clés : bien commun, gouvernance, ressource en eau, foggara. Dédicaces Je dédie ce modeste travail à : A mes très chers parents .Aucun hommage ne pourrait être à la hauteur de l’amour dont ils ne cessent de me combler. Que dieu leur procure bonne santé et longue vie. -

A Case Study of Solar Photovoltaic Generator System at Different Locations in Algeria

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 4, ISSUE 03, MARCH 2015 ISSN 2277-8616 A Case Study Of Solar Photovoltaic Generator System At Different Locations In Algeria Salmi Mohamed, Yarub Al-Douri Abstract: The aim of this study is the evaluation of a photovoltaic system at different locations in Algeria. We have calculated the system efficiency, the solar energy captured by the system and the electrical energy output. An economic study of a photovoltaic station has been done by estimating the cost of this project operating for a period of 25 years. To achieve this goal, we have selected four regions of the Algerian territory, differing in their climatological parameters: Algiers, Constantine, Oran and Tamanrasset. The measured monthly global solar radiation and temperatures values are taken during six years (2000-2005) from the different meteorological stations. The obtained results have revealed that the calculated electrical power for Tamanrasset was the highest one (3581kWh), the best efficiency was in Constantine (10.3%), however the lowest cost of the project was in Algie4rs and Oran (769.7kDZ). Index Terms— Solar Radiation; Photovoltaic’s Generator, Estimation; Electrical Power; Algeria. ———————————————————— 1 INTRODUCTION 2 ALGERIAN METEOROLOGICAL SITES Nowadays, the solar energy is one of the most powerful and The following data are used in this work: promising renewable energies for the future. This clean energy is inexhaustible and is quite available in the majority of the 2.1 Average monthly temperature measured at several world for profitable applications. Indeed, the power of solar meteorological stations radiation on the ground is about 950W/m2. The total amount of solar energy received at the ground during a week overtakes 2.2 Average monthly global solar radiation the energy produced by the world’s reserves of petrol, coal, We took the best model obtained in the modeling of solar gas and Uranium. -

Journal Officiel Algérie

N° 47 Mercredi 19 Dhou El Kaada 1434 52ème ANNEE Correspondant au 25 septembre 2013 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE CONVENTIONS ET ACCORDS INTERNATIONAUX - LOIS ET DECRETS ARRETES, DECISIONS, AVIS, COMMUNICATIONS ET ANNONCES (TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE) DIRECTION ET REDACTION Algérie ETRANGER SECRETARIAT GENERAL Tunisie (Pays autres DU GOUVERNEMENT ABONNEMENT Maroc que le Maghreb) ANNUEL Libye WWW. JORADP. DZ Mauritanie Abonnement et publicité: IMPRIMERIE OFFICIELLE 1 An 1 An Les Vergers, Bir-Mourad Raïs, BP 376 ALGER-GARE Tél : 021.54.35..06 à 09 Edition originale….........….........…… 1070,00 D.A 2675,00 D.A 021.65.64.63 Fax : 021.54.35.12 Edition originale et sa traduction....... 2140,00 D.A 5350,00 D.A C.C.P. 3200-50 ALGER (Frais d'expédition en TELEX : 65 180 IMPOF DZ BADR: 060.300.0007 68/KG sus) ETRANGER: (Compte devises) BADR: 060.320.0600 12 Edition originale, le numéro : 13,50 dinars. Edition originale et sa traduction, le numéro : 27,00 dinars. Numéros des années antérieures : suivant barème. Les tables sont fournies gratuitement aux abonnés. Prière de joindre la dernière bande pour renouvellement, réclamation, et changement d'adresse. Tarif des insertions : 60,00 dinars la ligne JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE N° 47 19 Dhou El Kaada 1434 2 25 septembre 2013 S O M M A I R E DECRETS Décret exécutif n° 13-319 du 10 Dhou El Kaada 1434 correspondant au 16 septembre 2013 portant virement de crédits au sein du budget de fonctionnement du ministère de l'agriculture et du développement rural...................................................... -

Journées Porte Ouverte

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE Ministère de l’agriculture et du développement rural Direction Générale des Forêts COMPTE RENDU DE LA CELEBRATION DE LA JOURNEE MONDIALE DES ZONES HUMIDES 2012 EN ALGERIE Comme chaque année, l’Algérie célèbre la journée mondiale des zones humides pour commémorer la signature de la convention de Ramsar, le 2 février 1971, dans la ville Iranienne de Ramsar, le thème suggéré Cette année par la convention porte sur : « le tourisme dans les zones humides : une expérience unique », avec pour slogan « le tourisme responsable, tout benef’ pour les zones humides et les populations» En Algérie, cette journée a été célébrée au niveau central et des structures déconcentrées, gestionnaires des zones humides, que sont les conservations des forêts de wilayas, les parcs nationaux et les centres cynégétiques. Au niveau central : Un riche programme a été mis en œuvre par la Direction Générale des Forêts en collaboration avec le Centre Cynégétique de Réghaia au niveau du lac de Réghaia (CCR) en présence des cadres gestionnaires des zones humides : - Présentation du plan de gestion de la zone humide de Réghaia - Visite guidée au niveau du centre d’éducation et de sensibilisation du public (ateliers d’animations en activité) : • ateliers de coloriages, confection de masques et poupées marionnettes • animation par un magicien et un clown • concours de dessin d’enfants • projection continue de films sur les zones humides • observation de l’avifaune du lac de Réghaia - Plantation symbolique au niveau de l’aire -

SMUGGLING of MIGRANTS from WEST AFRICA to EUROPE What Is the Nature of the Market?

4.2. From Africa to Europe: Flow map BM 01.03.09 SPAIN ITALY TURKEY Mediterranean Atlantic Sea Ocean Lampedusa GREECE (ITALY) MALTA CANARY TUNISIA ISLANDS MOROCCO (SPAIN) ALGERIA Western Sahara LIBYA EGYPT MAURITANIA Red Sea MALI SENEGAL SUDAN CHAD THE GAMBIA NIGER GUINEA-BISSAU GUINEA BURKINA FASO BENIN SIERRA Flows of irregular migrants TOGO LEONE CÔTE discussed in this chapter D’IVOIRE LIBERIA GHANA NIGERIA 1,000 km SMUGGLING OF MIGRANTS FROM Figure 19: Region of origin of irregular WEST AFRICA TO EUROPE migrants detected in Europe Evolution of measured apprehensions at several European countries' borders, 1999-2008 (vertical scales are differents) Migrant smuggling occurs most frequently along the fault 300,000 lines between twoMigrants regions appr ehendedof vastly in Spain different levels of Migrantsdevel- apprehended250,000 in Italy 26,140 Migrants apprehended in Malta at sea border (thousands) (thousands) 23,390and Africans apprehended in Greece opment, such as West Europe and West Africa. Though the (thousands) 20,465 30 Sahara Desert and theStrait Mediterranean of Gibraltar/ Sea pose formidable50 200,000 3 Alborean Sea Canary Islands 20 Malta 17,665 obstacles, thousands of people cross them each year in40 order 2.5 Rest of Italy150,000 10 2 to migrate irregularly. Almost all of those who choose30 to do Sicily* Egyptians 244,495 230,555 in Greece so require assistance, and the act of rendering this assistance 100,000 1.5 212,680 20 Somali 171,235 for gain constitutes the crime of migrant smuggling.40 1 in Greece 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 10 Sardinia 50,000 0.5 In recent years, about 9% of irregular migrants detected in 0 Europe came from West Africa. -

Les Routes Non Revêtues En Algérie

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DES TRAVAUX PUBLICS DIRECTION DES ROUTES LES ROUTES NON REVETUES EN ALGERIE Etabli par : Mademoiselle SEBAA Nacéra Février 2006 1 SOMMAIRE I. INTRODUCTION II. LE RESEAU ROUTIER ALGERIEN - A/ Présentation du Réseau Routier - B/ Répartition du Réseau Routier - C/ Etat du Réseau Routier Revêtu III. PRESENTATION DU RESEAU NON REVETU - A/ Consistance du Réseau Routier Non Revêtu - B/ Etat du Réseau Routier Non Revêtu IV. GENERALITES SUR LES PISTES SAHARIENNES - A/ Définition - B/ Particularité des Pistes Sahariennes - C/ Classification des Pistes Sahariennes • Les Pistes Naturelles • Les Pistes Améliorées • Les Pistes Elaborées V. LE RESEAU DES PISTES SAHARIENNES - A/ Identification des Principales Pistes Sahariennes - B/ Etat des Pistes Sahariennes - C/ Balisage - D/ Trafics Existants VI. CONTEXTE DU SAHARA ALGERIEN - A/ Contexte Climatique - B/ Nature des Sols Rencontrés au Sud - C/ Géotechnique VII. LES DIFFICULTEES DES PISTES SAHARIENNES A/ Les Dégradations • La Tôle Ondulée • Fech Fech • Affleurement Rocheux B/ Les Obstacles • Zones d’Ensablement • Ravinement • Passage d’Oued VIII. NOMENCLATURES DES TACHES D’ENTRETIEN DES PISTES SAHARIENNES - A/ Les Taches Ponctuelles - B/ Les Taches Périodiques à Fréquences Elevée - C/ Les Taches Périodiques à Faibles Fréquence 2 IX. LES DIFFERENTS INTERVENANTS DANS L ‘ENTRETIEN DES PISTES SAHARIENNES EN ALGERIE - A/ Au Niveau de La Central( MTP/DEER) - B/ Au Niveau de la wilaya (DTP/SEER) - C/ Au Niveau Local ( Subdivision Territoriale) X. LA STRATEGIE ADOPTEE PAR LE SECTEUR DES TRAVAUX PUBLICS EN MATIERE DE PISTES SAHARIENNES - A/ L e Congres de BENI ABBES • Introduction • Problématique de l’Entretien des Pistes • Recommandation et politique adoptée - B/Les Nouvelles Actions Entreprise par le Secteur des Travaux Publics 1) Etude de Stratégie et de Planification de l’Entretien du Réseau Non Revêtu du Grand Sud Algérien. -

Bouda - Ouled Ahmed Timmi Tsabit - Sebâa- Fenoughil- Temantit- Temest

COMPETENCE TERRITORIALE DES COURS Cour d’Adrar Cour Tribunaux Communes Adrar Adrar - Bouda - Ouled Ahmed Timmi Tsabit - Sebâa- Fenoughil- Temantit- Temest. Timimoun Timimoun - Ouled Said - Ouled Aissa Aougrout - Deldoul - Charouine - Adrar Metarfa - Tinerkouk - Talmine - Ksar kaddour. Bordj Badji Bordj Badj Mokhtar Timiaouine Mokhtar Reggane Reggane - Sali - Zaouiet Kounta - In Zghmir. Aoulef Aoulef - Timekten Akabli - Tit. Cour de Laghouat Cour Tribunaux Communes Laghouat Laghouat-Ksar El Hirane-Mekhareg-Sidi Makhelouf - Hassi Delâa – Hassi R'Mel - - El Assafia - Kheneg. Aïn Madhi Aïn Madhi – Tadjmout - El Houaita - El Ghicha - Oued M'zi - Tadjrouna Laghouat Aflou Aflou - Gueltat Sidi Saâd - Aïn Sidi Ali - Beidha - Brida –Hadj Mechri - Sebgag - Taouiala - Oued Morra – Sidi Bouzid-. Cour de Ghardaïa Cour Tribunaux Communes Ghardaia Ghardaïa-Dhayet Ben Dhahoua- El Atteuf- Bounoura. El Guerrara El Guerrara - Ghardaia Berriane Sans changement Metlili Sans changement El Meniaa Sans changement Cour de Blida Cour Tribunaux Communes Blida Blida - Ouled Yaïch - Chréa - Bouarfa - Béni Mered. Boufarik Boufarik - Soumaa - Bouinan - Chebli - Bougara - Ben Khellil – Ouled Blida Selama - Guerrouaou – Hammam Melouane. El Affroun El Affroun - Mouzaia - Oued El Alleug - Chiffa - Oued Djer – Beni Tamou - Aïn Romana. Larbaa Larbâa - Meftah - Souhane - Djebabra. Cour de Tipaza Cour Tribunaux Communes Tipaza Tipaza - Nador - Sidi Rached - Aïn Tagourait - Menaceur - Sidi Amar. Kolea Koléa - Douaouda - Fouka – Bou Ismaïl - Khemisti – Bou Haroum - Chaïba – Attatba. Hadjout Hadjout - Meurad - Ahmar EL Aïn - Bourkika. Tipaza Cherchell Cherchell - Gouraya - Damous - Larhat - Aghbal - Sidi Ghilès - Messelmoun - Sidi Semaine – Beni Milleuk - Hadjerat Ennous. Cour de Tamenghasset Cour Tribunaux Communes Tamenghasset Tamenghasset - Abalessa - Idlès - Tazrouk - In Amguel - Tin Zaouatine. Tamenghasset In Salah Sans changement In Guezzam In Guezzam.