CEO-Water-Mandate-Partnership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

Hoima Profile.Indd

Hoima District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 HOIMA DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE a Acknowledgment On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Mr. Odong Martin, Disaster Management Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred-Early Warning system Programmer. My appreciation also goes to Hoima District Team; 1. Mr. Luke L.L Lokuda – Chief Administrative Officer 2. Ms. Nyangoma Joseline – District Natural Resources Officer 3. Ms. Nsita Gertrude - District Environment Officer The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees HOIMA DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The multi-hazard vulnerability profile outputs from this assessment was a combination of spatial modeling using socio-ecological spatial layers (i.e. -

Annual Crime Report 2019 Public

P ANDA OLIC UG E PR E OTE RV CT & SE P ANDA OLIC UG E PRO E TEC RV T & SE UGANDA POLICE Annual Crime Report 2019 Annual Crime Report - 2019 Page I 1 P ANDA OLIC UG E PR E OTE RV CT & SE POLICE DA AN G U E V R E C & S PROTE T Annual Crime Report 2019 Annual Crime Report - 2019 P ANDA OLIC UG E PR E OTE RV CT & SE Mandate The Uganda Police Force draws its mandate from the constitution of Uganda Chapter Twelve, Article 212 that stipulates the functions of the force as: (a) to protect life and property; (b) to preserve law and order; (c) to prevent and detect crime; and (d) to cooperate with the civilian authority and other security organs estab- lished under this Constitution and with the population generally. Vision “An Enlightened, Motivated, Community Oriented, Accountable and Modern Police Force; geared towards a Crime free society”. Mission “To secure life and property in a committed and Professional manner, in part- nership with the public, in order to promote development Annual Crime Report - 2019 P ANDA OLIC UG E PR E OTE RV CT & SE ADMINISTRATIVE AND PLANNING MACRO STRUCTURE FOR THE UGANDA POLICE FORCE ADMINISTRATIVE AND PLANNING MACRO STRUCTURE FOR THE UGANDA POLICE FORCE Inspector General of Police Police Authority Deputy Inspector General of Police Chief of Joint Staff Directorate of Police Fire Directorate of Human Rights Directorate of Operations Directorate of Traffic & Prevention and Rescue and Legal Services Road Safety Services Directorate of ICT Directorate of Counter Directorate of Police Health Directorate of INTERPOL -

Kingfisher Oil Development Surface Water

October 2017 CNOOC UGANDA LIMITED KINGFISHER OIL PROJECT, HOIMA DISTRICT, UGANDA ‐ SURFACE WATER SPECIALIST REPORT VERSION Submitted to: The Executive Director National Environment Management Authority, NEMA House, Plot 17/19/21 Jinja Road, P. O. Box 22255 Kampala, Uganda READY VOLUME 4, STUDY 2 4, STUDY VOLUME – PRINT FINAL Report Number: 1776816‐321512‐13 REPORT Distribution: 1 x electronic copy CNOOC Uganda Limited 1 x electronic copy NEMA 1 x electronic copy Eco & Partner 1 x electronic copy Golder SURFACE WATER SPECIALIST REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents hydrology baseline information and an impact assessment of surface water hydrology affected by the Project. An understanding of surface water hydrological conditions prior to mine oil and gas development is essential to assess changes in water availability that could affect local users. Changes in hydrology can also affect water quality and other resources such as fish habitat, vegetation and wildlife. Hydrological data is further required to design mine oil and gas facilities (e.g. culverts, channels and storage ponds). The regional climate in the area is described as tropical with a distinct wet and dry season. Rainfall over the study area catchment varies between 700 mm and 1 400 mm/ annum. Results of Global Climate Change models indicate that Uganda is likely to experience more extreme periods of intense rainfall and drought, while the rainfall seasons become more erratic and/or infrequent. The project site is located within the Kingfisher catchment and drains westwards into the south eastern embankments of Lake Albert. Kingfisher catchment is associated with a very high western rift escarpment that drains into Lake Albert via several scattered streams and wetlands flowing westwards. -

Table of Contents List of Tables

TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 PROJECT IMPACTS ................................................................................................................ 138 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 138 Summary of Impacts ................................................................................................................. 138 Impacts on Land ....................................................................................................................... 143 6.3.1 Land Requirements and Land Use Context ......................................................................... 143 Impacts on houses – Physical Displacement ........................................................................... 149 Impacts on other structures ...................................................................................................... 153 Impacts on Communal Buildings .............................................................................................. 159 Graves and Cultural Heritage Assets ....................................................................................... 160 Impacts on Crops and Economic Trees .................................................................................... 160 Impacts on Livelihood Activities – Economic Displacement ..................................................... 166 Impacts on Public Utilities/Infrastructure .................................................................................. -

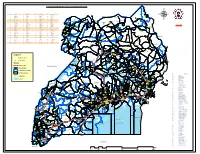

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

WETLANDS ATLAS Volume One: Kampala City, Mukono and Wakiso Districts

UGANDA WETLANDS ATLAS Volume One: Kampala City, Mukono and Wakiso Districts UGANDA WETLANDS ATLAS Volume One: Kampala City, Mukono and Wakiso Districts POPULAR VERSION © Government of Uganda (2016) All Rights reserved. CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: WETLANDS OVERVIEW .....................1 CHAPTER 4: WETLANDS IN MUKONO The importance of wetlands............................................2 DISTRICT.......................................................................15 Drivers of wetlands degradation......................................2 A threatened wetland: Namanve wetland........................15 Population............................................................................2 The problem .......................................................................16 Agriculture...........................................................................3 Impacts.................................................................................16 Industrial development......................................................4 Recommendations...............................................................16 Owning land in wetlands.................................................4 Factors allowing ownership of land in wetlands.............5 CHAPTER 5: WAKISO DISTRICT................................19 A well-kept wetland: Lutembe Bay wetlands...................19 CHAPTER 2: WETLANDS IN KAMPALA, MUKONO The problem........................................................................20 AND WAKISO.................................................................7 -

MAAIF-Annual-Perform

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, ANIMAL INDUSTRY AND FISHERIES DRAFT ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/2020 OCTOBER 2020 Foreword This agricultural sector annual performance covers the period July 2019 to June 2020. The report provides an assessment of the sector performance and it also highlights a review of undertakings agreed to in the JASAR 2018. The information presented covers the MAAIF structure and mandate, Crops, Livestock; Fisheries sub-sectors performance, Agriculture Extension Services, Agriculture Infrastructure, Mechanization and Water for Agricultural production, National Agriculture Advisory Services (NAADS) and National Agriculture Research Organization (NARO). The document is an annual publication through which key statistical information derived from routine monitoring visits and administrative records of the Ministry Department and Agencies (MDAs) are disseminated. The Ministry appreciates contributions of all stakeholders in implementation of the FY 2019/20 sector initiatives and the political leadership as well as the agricultural sector Development Partners for their guidance. The Ministry welcomes constructive comments from stakeholders that aim at enhancing the quality of its future publications. At their convenience, readers are encouraged to send constructive comments to the under signed, and or the editorial team. It is my sincere hope that the information in this publication will be used to make informed decisions. Pius Wakabi Kasajja PERMANENT SECRETARY ii Table of Contents ACRONYMS -

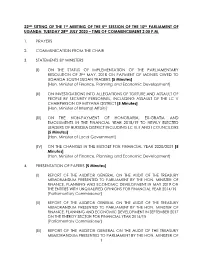

Tuesday 28Th July 2020 – Time of Commencement 2.00 P.M

22ND SITTING OF THE 1ST MEETING OF THE 5TH SESSION OF THE 10TH PARLIAMENT OF UGANDA: TUESDAY 28TH JULY 2020 – TIME OF COMMENCEMENT 2.00 P.M. 1. PRAYERS 2. COMMUNICATION FROM THE CHAIR 3. STATEMENTS BY MINISTERS (I) ON THE STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PARLIAMENTARY RESOLUTION OF 3RD MAY, 2018 ON PAYMENT OF MONIES OWED TO UGANDA-SOUTH SUDAN TRADERS [5 Minutes] [Hon. Minister of Finance, Planning and Economic Development] (II) ON INVESTIGATIONS INTO ALLEGATIONS OF TORTURE AND ASSAULT OF PEOPLE BY SECURITY PERSONNEL, INCLUDING ASSAULT OF THE LC V CHAIRPERSON OF MITYANA DISTRICT [5 Minutes] [Hon. Minister of Internal Affairs] (III) ON THE NON-PAYMENT OF HONORARIA, EX-GRATIA AND EMOLUMENTS IN THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2018/19 TO NEWLY ELECTED LEADERS OF BUKEDEA DISTRICT INCLUDING LC III, II AND I COUNCILORS [5 Minutes] [Hon. Minister of Local Government] (IV) ON THE CHANGES IN THE BUDGET FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021 [5 Minutes] (Hon. Minister of Finance, Planning and Economic Development) 4. PRESENTATION OF PAPERS [5 Minutes] (I) REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE AUDIT OF THE TREASURY MEMORANDUM PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT BY THE HON. MINISTER OF FINANCE, PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN MAY 2019 ON THE ENTITIES WITH UNQUALIFIED OPINIONS FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2014/15 [Parliamentary Commissioner] (II) REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE AUDIT OF THE TREASURY MEMORANDUM PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT BY THE HON. MINISTER OF FINANCE, PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN SEPTEMBER 2017 ON THE ENERGY SECTOR FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2014/15 [Parliamentary Commissioner] (III) REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE AUDIT OF THE TREASURY MEMORANDUM PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT BY THE HON. -

National Nile Basin Water Quality Monitoring Baseline Report For

Nile Basin Initiative Transboundary EnvironmentalAction Project National Nile Basin Water Quality Monitoring Baseline Report for UGANDA NILEBASIN INITIATIVE THE NILE BASIN TRANSBOUNDARY ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION PROJECT BASELINE STUDY OF THE STATUS OF WATER QUALITY MONITORING IN UGANDA BY MOSES OTIM APRIL 2005 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................... IV LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................ V LIST OF BOXES........................................................................................................ VI ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .....................................................................VII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................VIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................IX 1.0 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................16 1.1 THE NILE BASIN............................................................................................16 1.2 THE NILE BASIN IN UGANDA...............................................................................17 1.3 GEOLOGY .......................................................................................................19 1.4 MINERALISATION...............................................................................................21 -

CURRICULUM VITAE for Patick Mucunguzi.Pdf

1 CURRICULUM VITAE 1. NAMES: Patrick Mucunguzi 2. YEAR OF BIRTH: 4th December 1957 3. CITIZENSHIP: Ugandan 4. RANK: Associate Professor 5. POSTAL ADDRESS: Makerere University, Department of Plant Sciences, Microbiology and Biotechnology, P. O. Box 7062, Kampala, Tel: 256-712-813610, E-mail: [email protected] 6. ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS i) 1979 - 1982: BSc. (Botany/Zoology) Second Class Honours, Upper Division, Makerere University ii) 1989 - 1992: M.Sc. (Environmental Sciences) Makerere University iii) 1997 – 2001: PhD. (Botany) Makerere University 7. WORKING EXPERIENCE i) 1982 - 1988: Appointed as Teaching Assistant in the Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Makerere University, 12th October, 1982 ii) 1988 – 1992: Appointed as Staff Development Fellow in the Department of Botany, Makerere University. iii). 1992 – 1993: Appointed as Assistant Lecturer in the Department of Botany, Makerere University, 9th November, 1992 iv). 1994-1998: Appointed as Lecturer, Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Makerere University, 5TH July, 1994 v). 1998-2008: Promoted to a Senior Lecturer Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Makerere University, 9TH September, 1998 vi). 1998 - 2000: Appointed as an Assistant to the University Research Extension Coordinator (Faculty of Science) in the NARO/Makerere University Co-operation. vii). 2002-2004: Acting Head of Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Makerere University viii). 2004 – 2008: Head of Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Makerere University ix). 2008 to date: Promoted to an Associate Professor of Botany, Department of Plant Sciences, Microbiology and Biotechnology (formerly Botany) Faculty of Science, Makerere University, 20th May, 2008. x) 2005 – 2017: Field Attachment Coordinator, Department of Plant Sciences, Microbiology and Biotechnology (formerly Botany) 2 8. -

(Nema) Annual Corporate Report for 2018/19

ANNUAL CORPORATE a REPORT FOR 2018/19 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY (NEMA) ANNUAL CORPORATE REPORT FOR 2018/19 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY (NEMA) ANNUAL CORPORATE REPORT FOR 2018/19 Copyright © 2019 NEMA All rights reserved. Citation: NATIONAL ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY (NEMA) ANNUAL CORPORATE REPORT FOR 2018/19 ISBN: 978 - 9970 - 881 - 45 - 1 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY (NEMA) Plot 17/19/21 Jinja Road P.O. Box 22255 Kampala Uganda Tel: +256-414-251064/5/8 Fax: +256-414-257521 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.nema.go.ug Cover Page Picture: Entebbe Express Bridge. Photo Credit; Tony Achidria EDITORIAL TEAM Editor in Chief Fred Onyai Internal Monitoring and Evaluation Manager Technical Editors: Margaret Aanyu Environment Assessment Manager Aidan Asekenye Principal Environment Education Coordinator Francis Ogwal Natural Resources Manager- Biodiversity and Rangelands Patrick Rwera Finance Manager James Elungat Internal Audit Manager Monique Akullo Senior Internal Monitoring and Evaluation Officer Eva Wamala Mutongole Senior Librarian CORPORATE ANNUAL i REPORT FOR 2018/19 FOREWORD The National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) is the principal agency in Uganda responsible for the management of the environment by regulating, coordinating, monitoring and supervising all matters in the field of environment. The Authority is mandated to work in partnership with stakeholders most of whom include Lead Agencies, Local Governments, Ministries and strategic partners, to effectively manage Uganda’s environment to ensure sustainable development. The 2018/19 annual report describes the status of implementation of the Key Result Areas (KRAs) outputs and outcomes as stipulated in the Strategic Plan of NEMA that are based on its mandate, and statutory functions.