SPECIAL FEATURE the Lonely Islands Attu and Kiska, Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resource Utilization in Atka, Aleutian Islands, Alaska

RESOURCEUTILIZATION IN ATKA, ALEUTIAN ISLANDS, ALASKA Douglas W. Veltre, Ph.D. and Mary J. Veltre, B.A. Technical Paper Number 88 Prepared for State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence Contract 83-0496 December 1983 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To the people of Atka, who have shared so much with us over the years, go our sincere thanks for making this report possible. A number of individuals gave generously of their time and knowledge, and the Atx^am Corporation and the Atka Village Council, who assisted us in many ways, deserve particular appreciation. Mr. Moses Dirks, an Aleut language specialist from Atka, kindly helped us with Atkan Aleut terminology and place names, and these contributions are noted throughout this report. Finally, thanks go to Dr. Linda Ellanna, Deputy Director of the Division of Subsistence, for her support for this project, and to her and other individuals who offered valuable comments on an earlier draft of this report. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . e . a . ii Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION . e . 1 Purpose ........................ Research objectives .................. Research methods Discussion of rese~r~h*m~t~odoio~y .................... Organization of the report .............. 2 THE NATURAL SETTING . 10 Introduction ........... 10 Location, geog;aih;,' &d*&oio&’ ........... 10 Climate ........................ 16 Flora ......................... 22 Terrestrial fauna ................... 22 Marine fauna ..................... 23 Birds ......................... 31 Conclusions ...................... 32 3 LITERATURE REVIEW AND HISTORY OF RESEARCH ON ATKA . e . 37 Introduction ..................... 37 Netsvetov .............. ......... 37 Jochelson and HrdliEka ................ 38 Bank ....................... 39 Bergslind . 40 Veltre and'Vll;r;! .................................... 41 Taniisif. ....................... 41 Bilingual materials .................. 41 Conclusions ...................... 42 iii 4 OVERVIEW OF ALEUT RESOURCE UTILIZATION . 43 Introduction ............ -

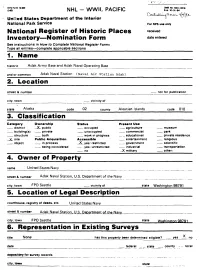

Adak Army Base and Adak Naval Operating Base and Or Common Adak Naval Station (Naval Air Station Adak) 2

N?S Ferm 10-900 OMB Mo. 1024-0018 (342) NHL - WWM, PACIFIC Eip. 10-31-84 Uncled States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS UM only National Register off Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections ' _______ 1. Name__________________ historic Adak Army Base and Adak Naval Operating Base and or common Adak Naval Station (Naval Air Station Adak) 2. Location street & number not (or publication city, town vicinity of state Alaska code 02 county Aleutian Islands code 010 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use __ district X public __ occupied __ agriculture __ museum building(s) private __ unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence X site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government __ scientific being considered .. yes: unrestricted industrial transportation __ no ,_X military __ other: 4. Owner off Property name United States Navy street & number Adak Naval Station, U.S. Department of the Navy city, town FPO Seattle vicinity of state Washington 98791 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. United States Navy street & number Adak Naval Station. U.S. Department of the Navy city, town FPO Seattle state Washington 98791 6. Representation in Existing Surveys y title None has this property been determined eligible? yes J^L no date federal _ _ state __ county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered _K original site __ good X_ ruins _X altered __ moved date _.__._. -

Terrestrial Mollusks of Attu, Aleutian Islands, Alaska BARRY ROTH’ and DAVID R

ARCTK: VOL. 34, NO. 1 (MARCH 1981), P. 43-47 Terrestrial Mollusks of Attu, Aleutian Islands, Alaska BARRY ROTH’ and DAVID R. LINDBERG’ ABSTRACT. Seven species of land mollusk (2 slugs, 5 snails) were collected on Attu in July 1979. Three are circumboreal species, two are amphi-arctic (Palearctic and Nearctic but not circumboreal), and two are Nearctic. Barring chance survival of mollusks in local refugia, the fauna was assembled overwater since deglaciation, perhaps within the last 10 OOO years. Mollusk faunas from Kamchatka to southeastern Alaska all have a Holarctic component. A Palearctic component present on Kamchatka and the Commander Islands is absent from the Aleutians, which have a Nearctic component that diminishes westward. This pattern is similar to that of other soil-dwelling invertebrate groups. RESUM& Sept espbces de mollusques terrestres (2 limaces et 5 escargots) furent prklevkes sur I’ile d’Attu en juillet 1979. Trois sont des espbces circomborkales, deux amphi-arctiques (Palkarctiques et Nkarctiques mais non circomborkales), et deux Nkarctiques. Si I’on excepte la survivance de mollusques due auhasard dans des refuges locaux, cette faune s’est retrouvke de part et d’autre des eauxdepuis la dkglaciation, peut-&re depuis les derniers 10 OOO ans. Les faunes de mollusques de la pkninsule de Kamchatkajusqu’au sud-est de 1’Alaska on toutes une composante Holarctique. Une composante Palkarctique prksente sur leKamchatka et les iles Commandeur ne se retrouve pas aux Alkoutiennes, oil la composante Nkarctique diminue vers I’ouest. Ce patron est similaire il celui de d’autres groupes d’invertkbrks terrestres . Traduit par Jean-Guy Brossard, Laboratoire d’ArchCologie de I’Universitk du Qukbec il Montrkal. -

World War II in Alaska

World War II in Alaska Front Cover: Canadian and American troops make an amphibious landing on the Aleutian island of Kiska, August 15, 1943. (Archives and Manuscripts Department, University of Alaska Anchorage) Rear Cover: Russian pilots participating in the Lend-Lease Program inspect an American fighter at Ladd Field near Fairbanks, circa 1944. (Alaska Historical Library, Juneau, Alaska) Publication funded by Alaska Support Office National Park Service 2000 U.S. Department of the Interior Anchorage, Alaska A Resource Guide for Teachers and Students Introduction This resource guide is designed to aid students and teachers in researching Alaska’s World War II history. Alaska’s role as battlefield, lend-lease transfer station, and North Pacific stronghold was often overlooked by historians in the post-war decades, but in recent years awareness has been growing of Alaska’s wartime past. This renewed interest generates exciting educational opportunities for students and teachers researching this chapter in the history of our state. Few people know that the only World War II battle fought on U.S. soil took place in Alaska or that Japanese forces occupied two Aleutian Islands for more than a year. Still fewer know of the Russian pilots who trained in Fairbanks, the workers who risked their lives building the Alaska Highway, or the Alaska Scouts who patrolled the Bering Sea coast. The lives of Alaskans were forever changed by the experience of war, and the history of that dramatic era is still being written. This resource guide begins with a map of important World War II sites and a summary of Alaska’s World War II experience. -

Fl'tjyvi" I RESULTS of a MARINE BIRD &'Ld MAMMAL SURVEY

-----~- r ¥l~~ S-eJ~;~(:? I fl'tJyVI" i RESULTS OF A MARINE BIRD &'lD MAMMAL SURVEY [ OF THE WESTERN ALEUTIAN ISLANDS SUMMER 1978 ,J l I :"I i Robert H. Day Brian E. Lawhead Tom J. Early Elaine B. Rhode ALEUTIAN ISLANDS NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE January 1979 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Title Author Page List of Figures i List of Tables vi I Introduction 1 II Census Techniques Day 4 III Island Descriptions Rhode 17 IV Island Species Accounts Day 34 V Avian Pre~ators Day 48 VI Marine Mammals Lawhead 54 VII Buldir Island Rhode 77 VIII Auklet Census Day 83 IX Murre Study Plots Lawhead and Day 88 X Beached Animal Surveys Day 115 XI Permanent Plots Day and Early 129 XII Pelagic Transects Early 157 XIII Terrestrial Transects Early 176 XIV Recotmnendations 184 Literature Cited 186 Appendix I Raw Island Transect Data 190 .,. .. :'" ,., ,- II Buldir Permanent Plots Data 200 III Agattu Murre Plot Data 217 IV Agattu Inland Transects Data 234 LIST OF FIGURES Figure No. Title Page No. 1 Schematic diagram of Least and Crested 11 Auklet activity patterns. 2 Location of the Baby Islands in the 19 Eastern Fox Group. 3 Baby Islands - Physical features. 20 4 Bogoslof Island - Physical features 22 in 1978. 5 The Near Island Group. 23 6 Agattu ,Island - Physica·1 features and 24 potenti~l campsites. 7 Alaid Island - Physical features and 26 potential campsites. 8 Nizki Island - Physical features and 27 potential campsites. 9 The Rat Island Group. 29 10 Bu1dir Island - Physical features and 30 potential campsites. 11 Kiska Island - Physical features and 31 potential campsites. -

THE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS: THEIR PEOPLE and NATURAL HISTORY

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WAR BACKGROUND STUDIES NUMBER TWENTY-ONE THE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS: THEIR PEOPLE and NATURAL HISTORY (With Keys for the Identification of the Birds and Plants) By HENRY B. COLLINS, JR. AUSTIN H. CLARK EGBERT H. WALKER (Publication 3775) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION FEBRUARY 5, 1945 BALTIMORE, MB., U„ 8. A. CONTENTS Page The Islands and Their People, by Henry B. Collins, Jr 1 Introduction 1 Description 3 Geology 6 Discovery and early history 7 Ethnic relationships of the Aleuts 17 The Aleutian land-bridge theory 19 Ethnology 20 Animal Life of the Aleutian Islands, by Austin H. Clark 31 General considerations 31 Birds 32 Mammals 48 Fishes 54 Sea invertebrates 58 Land invertebrates 60 Plants of the Aleutian Islands, by Egbert H. Walker 63 Introduction 63 Principal plant associations 64 Plants of special interest or usefulness 68 The marine algae or seaweeds 70 Bibliography 72 Appendix A. List of mammals 75 B. List of birds 77 C. Keys to the birds 81 D. Systematic list of plants 96 E. Keys to the more common plants 110 ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES Page 1. Kiska Volcano 1 2. Upper, Aerial view of Unimak Island 4 Lower, Aerial view of Akun Head, Akun Island, Krenitzin group 4 3. Upper, U. S. Navy submarine docking at Dutch Harbor 4 Lower, Village of Unalaska 4 4. Upper, Aerial view of Cathedral Rocks, Unalaska Island 4 Lower, Naval air transport plane photographed against peaks of the Islands of Four Mountains 4 5. Upper, Mountain peaks of Kagamil and Uliaga Islands, Four Mountains group 4 Lower, Mount Cleveland, Chuginadak Island, Four Mountains group .. -

Historical Timeline for Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge

Historical Timeline Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Much of the refuge has been protected as a national wildlife refuge for over a century, and we recognize that refuge lands are the ancestral homelands of Alaska Native people. Development of sophisticated tools and the abundance of coastal and marine wildlife have made it possible for people to thrive here for thousands of years. So many facets of Alaska’s history happened on the lands and waters of the Alaska Maritime Refuge that the Refuge seems like a time-capsule story of the state and the conservation of island wildlife: • Pre 1800s – The first people come to the islands, the Russian voyages of discovery, the beginnings of the fur trade, first rats and fox introduced to islands, Steller sea cow goes extinct. • 1800s – Whaling, America buys Alaska, growth of the fox fur industry, beginnings of the refuge. • 1900 to 1945 – Wildlife Refuge System is born and more land put in the refuge, wildlife protection increases through treaties and legislation, World War II rolls over the refuge, rats and foxes spread to more islands. The Aleutian Islands WWII National Monument designation recognizes some of these significant events and places. • 1945 to the present – Cold War bases built on refuge, nuclear bombs on Amchitka, refuge expands and protections increase, Aleutian goose brought back from near extinction, marine mammals in trouble. Refuge History - Pre - 1800 A World without People Volcanoes push up from the sea. Ocean levels fluctuate. Animals arrive and adapt to dynamic marine conditions as they find niches along the forming continent’s miles of coastline. -

Song Sparrow, Giant

Alaska Species Ranking System - Song Sparrow, Giant Song Sparrow, Giant Class: Aves Order: Passeriformes Melospiza melodia maxima Note: This assessment refers to this subspecies only. A species level report, which refers to all associated subspecies, is also available. Review Status: Peer-reviewed Version Date: 28 March 2019 Conservation Status NatureServe: Agency: G Rank:G5T4 ADF&G: Species of Greatest Conservation Need IUCN: Audubon AK:Yellow S Rank: USFWS: BLM: Final Rank Conservation category: V. Orange unknown status and either high biological vulnerability or high action need Category Range Score Status -20 to 20 0 Biological -50 to 50 -20 Action -40 to 40 16 Higher numerical scores denote greater concern Status - variables measure the trend in a taxon’s population status or distribution. Higher status scores denote taxa with known declining trends. Status scores range from -20 (increasing) to 20 (decreasing). Score Population Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Distribution Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Status Total: 0 Biological - variables measure aspects of a taxon’s distribution, abundance and life history. Higher biological scores suggest greater vulnerability to extirpation. Biological scores range from -50 (least vulnerable) to 50 (most vulnerable). Score Population Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Range Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) -2 Western and central Aleutian Islands (Gabrielson and Lincoln 1951; Patten and Pruett 2009; Gibson and Withrow 2015) from Attu Island to Amlia Island (Gibson and Withrow 2015). Estimated 27,000 sq. km (using GoogleMaps). Population Concentration in Alaska (-10 to 10) -10 No subspecies specific information, likely same as species: does not concentrate (Arcese et al. -

Distribution and Population Status of Whiskered Auklet in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska

DISTRIBUTION AND POPULATION STATUS OF WHISKERED AUKLET IN THE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS, ALASKA G. VERNON BYRD, Hawaiian Islands NWR, P.O. Box 87, Kilauea, Kauai, Hawaii 96754 DANIEL D. GIBSON, Universityof AlaskaMuseum, Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 The little known WhiskeredAuklet (Aethiapygrnaea) occurs only in the Aleutian(Figure 1), Commanderand Kurilislands of the North Pacific. In the Aleutian Islands it occurs from Unimak Pass to the Near Islands (Kesseland Gibson 1978), but the only documented nesting records are from Umnak Island (R.J. Gordon in litt.), Chagulak Island (Murie 1959), Atka Island (Turner 1886), and Buldir Island (Knudtsonand Byrd in press). This paper summarizesnew informationon the distributionof WhiskeredAuklet in the AleutianIslands, and providesa significantly higher estimateof the minimum population. METHODS Duringthe period 1972-1974 we were aboardthe R/V Aleutian Tern as it traveledto everymajor island in the Aleutians.In 1972 and 1974 nearlythe entireisland chain was traversed. In 1972 the trip was made during the breedingseason, but in 1974 observations were made in April, prior to nesting.In 1973 observationswere con- fined to the eastern Aleutians. Travel was generally confined to daylighthours so that continuousobservations could be made. One or two observerscounted birds within approximately 300 m of both sidesof the ship. The Aleutian Tern traveledat 16 km/h except when near islandswhen the speedwas reduced to as low as 8 km/h. Islandgroups within the Aleutiansare identifiedas follows:1) Fox Islands - Unimak Pass to Umnak Island (the area of each island groupends 16 km westof the westernmostisland, to includebirds associatedwith nestingcolonies); 2) Islandsof Four Mountains- Um- nak Island to Amukta Island; 3) Andreanor Islands- Amukta Island to UnalgaIsland; 4) Rat Islands- UnalgaIsland to BuldirIsland; 5) Near Islands - Buldir Island to Attu Island. -

Preliminary Volcano-Hazard Assessment for Great Sitkin Volcano, Alaska

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Preliminary Volcano-Hazard Assessment for Great Sitkin Volcano, Alaska Open-File Report 03–112 no O a b c l s o e r V v a a t k o s r a l y A U S S G G This report is preliminary and subject to revision G S D as new data become available. It does not conform - A U A F / G I - to U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. The Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO) was established in 1988 to monitor dangerous volcanoes, issue eruption alerts, assess volcano hazards, and conduct volcano research in Alaska. The cooperating agencies of AVO are the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute (UAFGI), and the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys (ADGGS). AVO also plays a key role in notification and tracking eruptions on the Kamchatka Peninsula of the Russian Far East as part of a formal working relationship with the Kamchatkan Volcanic Eruptions Response Team. Cover photograph: Great Sitkin Volcano from the north shore of Adak Island, July 2000. Photograph by C.F. Waythomas, U.S. Geological Survey. Preliminary Volcano-Hazard Assessment for Great Sitkin Volcano, Alaska By Christopher F. Waythomas, Thomas P. Miller, and Christopher J. Nye U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 03–112 Alaska Volcano Observatory Anchorage, Alaska 2003 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Summer Distribution of Pelagic Birds in Bristol Bay, Alaska

SUMMER DISTRIBUTION OF PELAGIC BIRDS IN BRISTOL BAY, ALASKA JAMES C. BARTONEK Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife Jamestown, North Dakota 58401 AND DANIEL D. GIBSON Alaska Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit Bristol Bay and its islands, the embayments, the western end of the Aleutian Islands. Shun- lagoons, and other estuaries along the north tov (1966) and Irving et al. (1970) reported side of the Alaska Peninsula, and the nesting on the wintering birds of the Bering Sea. Un- cliffs on the north shore, are seasonally im- analyzed data on birds observed in the Bering portant to vast numbers of seabirds, water- Sea are published with the oceanographic and fowl, and shorebirds that either breed, summer, fisheries records of the RV Osharo Maru winter, or stopover there during migration. ( Hokkaido University 1957-68 ) . This productive southeast corner of the Bering Osgood ( 1904), Murie ( 1959), and Gabriel- Sea is also used by sea otters and several spe- son and Lincoln (1959) summarized the in- cies of pinnipeds and cetaceans, and it is the formation on birds of the lands bordering site of the worlds largest salmon fishery. Bristol Bay. Dal1 (1873) and Cahn (1947) Petroleum development is planned for this described the birds on and about Unalaska area and, judging from the past history of nu- Island, the westernmost point included within merous oil spills in nearby Cook Inlet, could our area of study. Except for Turners’ (1886) have deleterious effects on this rich fauna. brief account of the birds of Cape Newenham This possibility prompted investigations of and recent unpublished administrative reports the migratory birds, including the pelagic of the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, species, that could provide the year-round in- the immense bird colonies along the western formation on distribution and numbers nec- half of the north shore of Bristol Bay, includ- essary to protect birds from the possible haz- ing Cape Newenham and nearby islands, and ards of petroleum development and shipping. -

2015 Aleutian World War II Calendar

ALEUTIAN WORLD WAR II NATIONAL HISTORIC AREA 2015 CALENDAR VS-49 Pilots in Aerology Building H. Marion Thornton Photographs,1942-1945. ASL-P338-1663. uring World War II the remote Aleutian corporation for Unalaska) and the National Alaska Affiliated Areas Calendar research and design was funded by DIslands, home to the Unangan (Aleut Park Service provides them with technical 240 West 5th Ave., Anchorage, Alaska 99501 the National Park Service Affiliated Areas people) for over 8,000 years, became one of assistance. Through this cooperative (907) 644-3503 Program in support of the Aleutian World War the fiercely contested battlegrounds of the partnership, the Unangan are the keepers of II National Historic Area, in cooperation with Pacific. This thousand-mile-long archipelago their history and invite the public to learn more Ounalashka Corporation the Aleutian Pribilof Heritage Group. saw the first invasion of American soil about their past and present. P.O. Box 149 since the War of 1812, a mass internment Unalaska, Alaska 99685 Front Cover: “Ten Minutes Rest–Kiska,” by of American civilians, a 15-month air war, For information about the Aleutian World War Visitor Information (907) 581-1276 E.J. Hughes. 19710261-3873. Beaverbrook and one of the deadliest battles in the Pacific II National Historic Area, visit our web site at: Visitor Center (907) 581-9944 Collection of War Art. © Canadian War Theatre. www.nps.gov/aleu/ or contact: Museum In 1996 Congress designated the Aleutian This Page: Aerology Building, circa 1970s. World War II National Historic Area to Restored, this building now serves as the interpret, educate, and inspire present and Aleutian World War II Visitor Center.