The Imagery of Interior Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

Emotionet: an Accurate, Real-Time Algorithm for the Automatic Annotation of a Million Facial Expressions in the Wild

EmotioNet: An accurate, real-time algorithm for the automatic annotation of a million facial expressions in the wild C. Fabian Benitez-Quiroz*, Ramprakash Srinivasan*, Aleix M. Martinez Dept. Electrical and Computer Engineering The Ohio State University ∗These authors contributed equally to this paper. Abstract it were possible to annotate each face image very fast by an expert coder (say, 20 seconds/image)1, it would take 5,556 Research in face perception and emotion theory requires hours to code a million images, which translates to 694 (8- very large annotated databases of images of facial expres- hour) working days or 2:66 years of uninterrupted work. sions of emotion. Annotations should include Action Units This complexity can sometimes be managed, e.g., in im- (AUs) and their intensities as well as emotion category. age segmentation [18] and object categorization [17], be- This goal cannot be readily achieved manually. Herein, cause everyone knows how to do these annotations with we present a novel computer vision algorithm to annotate minimal instructions and online tools (e.g., Amazon’s Me- a large database of one million images of facial expres- chanical Turk) can be utilized to recruit large numbers of sions of emotion in the wild (i.e., face images downloaded people. But AU coding requires specific expertise that takes from the Internet). First, we show that this newly pro- months to learn and perfect and, hence, alternative solutions posed algorithm can recognize AUs and their intensities re- are needed. This is why recent years have seen a number liably across databases. To our knowledge, this is the first of computer vision algorithms that provide fully- or semi- published algorithm to achieve highly-accurate results in automatic means of AU annotation [20, 10, 22,2, 26, 27,6]. -

L'autre Siècle De Messer Gaster? Physiologies De L'estomac Au Xixe

L’Autre siècle de Messer Gaster ? Physiologies de l’estomac au XIXe siècle Bertrand Marquer To cite this version: Bertrand Marquer. L’Autre siècle de Messer Gaster ? Physiologies de l’estomac au XIXe siècle. Hermann, 2017, ”Hors collection”. hal-03005150 HAL Id: hal-03005150 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03005150 Submitted on 13 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. L’AUTRE SIÈCLE DE MESSER GASTER ? Physiologies de l’estomac dans la littérature du e XIX siècle Bertrand Marquer Du même auteur Les Romans de la Salpêtrière. Réceptions d’une scénographie clinique : Jean-Martin Charcot dans l’imaginaire fin-de-siècle, Genève, Droz, coll. « Histoire des idées et Critique Littéraire », 2008. Naissance du fantastique clinique. La crise de l’analyse dans la littérature fin-de-siècle, Paris, Hermann, coll. « Savoir lettres », 2014. 2 Pour Anne-Laure, Lise et Lucie. 3 INTRODUCTION 4 « Holà ! Messer Gaster, voici votre règne ! » Lorsqu’il entend rendre compte de la portée philosophique de La Peau de chagrin, Philarète Chasles associe le XIXe siècle à l’accomplissement du « règne » de « Messer Gaster1 », l’allégorie de l’estomac symbolisant, selon lui, la domination du matérialisme. -

Types of Weltschmerz in German Poetry

TY PE S O F WE LT S C H M ERZ I N GERMAN POETRY ' L R D B RA N P h D A F E U . WILH ELM , S OM ETI M E F E LLOW I N GE RMAN I C LANGUA GE S AN D U CO L U M B I A U NI V E RS I TY LITERAT RES . mmmm TH E CO LU MB I A UNIVERSITY P RES S TH E MAC MI LLAN COM PANY , A GE NT S L ONDON : MA CM I L LA N Co L TD . 1 905 A ll rig h ts reserved C OLU MBI A UNIV ERSI TY GERMANI C STU DI ES Edite d WI LLI AM C AR P ENT ER an d by H . CALVIN THOMAS V ol I . SCAN DINAVIAN INFLUENCE ON SOUT H E RN W ND S A o b u o t o LO LA C O TCH . C ntri ti n the St u dy o f the Lingu istic Re latio ns o f English an d d a a B O B F OM h D o S a . G O S P . 8v c n in vi n y E RG E T IA L , , P c ne t . a . xv ! 82 . p per , pp ri e , S M B o e a No . OS G . a G 2 IAN IN ER ANY ibli gr phy , en r l ’ Su e Ossi an s n fl u c o n K o s ock an d t he a ds rv y , I en e l p t B r . -

Table of Contents

A periodic pubblication from the Italian Trade Volume 12 Issue1 .it italian trade 1 Table of contents 22. CREDITS EDITORIALS 24. “Italy and Miami: a long lasting bond of friendship”: a message from Tomas Regalado, Mayor of the City of Miami 26. “The US Southeast, a thriving market for Italian companies”: a message from Gloria Bellelli, Consul General of Italy in Miami 28. “The United States of America, a strategic market for Italian food industry”: a message from Gian Domenico Auricchio, President of Assocamerestero 30. “25 years supporting Italy and its businesses”: a message from Gianluca Fontani, President of Italy-America Chamber of Commerce Southeast SPECIAL EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTIONS 32. “Andrea Bocelli, when simplicity makes you the greatest”, interview with Andrea Bocelli, Italian classical crossover tenor, recording artist, and singer-songwriter. 40. “Santo Versace, Style is the Man!”, interview with Santo Versace, President of Gianni Versace Spa 47. “Italians in Miami: a unique-of-its-kind community”, by Antonietta Di Pietro Italian Instructor in the Department of Modern Languages at Florida International University 53. “Italy and the US: a strong relationship” by Andrea Mancia e Simone Bressan, Journalists and Bloggers THE “MADE IN ITALY AMBASSADOR AWARD” WINNERS 58. “Buccellati, a matter of generations”, interview with Andrea Buccellati, President and Creative Director of Buccellati Spa 63. “The Made in Italy essence” interview with Dario Snaidero, CEO of Snaidero USA INTRODUCING “THE BEST OF ITALY GALA NIGHT” 69. “The Best of Italy Gala Night” Program THE PROTAGONISTS OF “THE BEST OF ITALY GALA NIGHT” 76. “Alfa Romeo, Return of a legend”, by Alfa Romeo 82. -

Grand Theft Cosmos Free

FREE GRAND THEFT COSMOS PDF Eddie Robson,Paul McGann,Sheridan Smith | none | 10 May 2008 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781844353064 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom Codes Display Text Post a comment. Untitled Page. The Doctor and Lucie visit nineteenth-century Sweden and become embroiled in an attempt to steal the infamous Black Diamond. But the stone is guarded by forces not of this Grand Theft Cosmos Breathless Romantic: Oh my, what luminous characterisation of the eighth Doctor! It reminds me very strongly of the same irreverence with which the sixth Doctor tackled Dr Who and the Pirates, a sense of casual abandon and a Grand Theft Cosmos sense that he is making it all up as he Grand Theft Cosmos along with great pleasure! When he announces that they are going to steal the painting he is positively foaming at the mouth with excitement! This episode suggests a trainspotter Doctor with a geeky notepad licking his pencil. It transpires that the works of Tardelli are obscure because the Doctor has done his utmost to find them wherever he can and destroy them! He tells us of an adventure in Rome where he discovered that Tardelli could warp the fabric of reality and he was trying to influence the Pope. When criticised for his time crafts lack of stealth making discreet landings impossible the Doctor bemoans that it is exceedingly difficult to making the rendering of space and time any quieter. He indulges in a spot of swordplay and I bet he looked strikingly Byronesque with his flowing hair and velvet jacket! With a certain crushing inevitability he always shows up. -

Narrative and Representation in French Colonial Literature of Indochina

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Narrative and Representation in French Colonial Literature of Indochina. Jean Marie turcotte Walls Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Walls, Jean Marie turcotte, "Narrative and Representation in French Colonial Literature of Indochina." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5703. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5703 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the qualify of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

Goran BREGOVIC's KARMEN with a Happy End a Gypsy Opera Played

Goran BREGOVIC’s KARMEN with a Happy End A gypsy opera played and sung by Goran Bregovic and his Wedding and Funeral Band for KAMARAD production libretto & music: Goran Bregovic script co-writer and all the best ideas: Mirjana Bobic Mojsilovic orchestration: Nino Ademovic programming & sound: Dusan Vasic Slave Celevski Nikola Vukovic Sasa Jaksic - Zika Translations into Roma Ljuan Koka Translation into English Maria Rankov Recorded and mixed in KAMARAD Studios, Belgrade Mastering in METROPOLIS Studios, London * * * * CHARACTERS Vaska Jankovska: KLEOPATRA - A beautiful gypsy with a band-aid on her fore-arm who tells fortune in a tv show. Engages in a telephone seduction-game with BAKIA, passing herself off for Nena, a strip- tease girl. In the opera she plays the late Karmen. Bokan Stankovic: BAKIA - Street-sweeper, a trumpet player. In the opera he plays his own uncle, the late Fuad Kostic. Milos Mihajlovic: MILOS - Baritone player in Fuad’s orchestra. Dejan Manigodic: Deki - Tuba player in Fuad’s orchestra, he now circumcises Stojan Dimov: Stole - Sax player in Fuad’s orchestra Dalibor Lukic: trumpet player - In the opera he plays Captain EMILIO, leader of a police brass band. Alen Ademovic: Alen - Traditional drums payer in Fuad’s orchestra. In the opera he plays CEausesCu, the pimp Aleksandar Rajkovic: ACA - Baritone, gipsy street musicians Goran Bregovic: BREGA - Snare-drum player in Fuad’s orchestra, now receptionist in a hotel at the Central Station Ludmila Radkova-Trajkova: MICHAELA, Emilio’s fiance who plays accordion - In the opera she plays a worker from the Tobacco Factory, a prostitute Daniela Radkova-Aleksandrova: SINGER - in the opera she plays a worker from the Tobacco Factory, and a prostitute KLEOPATRA: Here I am. -

Homage to Alberto Moravia: in Conversation with Dacia Maraini At

For immediate release Subject : Homage to Alberto Moravia: in conversation with Dacia Maraini At: the Italian Cultural Institute , 39 Belgrave Square, London SW1X 8NX Date: 26th October 2007 Time: 6.30 pm Entrance fee £5.00, booking essential More information : Press Officer: Stefania Bochicchio direct line 0207 396 4402 Email [email protected] The Italian Cultural Institute in London is proud to host an evening of celebration of the writings of Alberto Moravia with the celebrated Italian writer Dacia Maraini in conversation with Sharon Wood. David Morante will read extracts from Moravia’s works. Alberto Moravia , born Alberto Pincherle , (November 28, 1907 – September 26, 1990) was one of the leading Italian novelists of the twentieth century whose novels explore matters of modern sexuality, social alienation, and existentialism. or his anti-fascist novel Il Conformista ( The Conformist ), the basis for the film The Conformist (1970) by Bernardo Bertolucci; other novels of his translated to the cinema are Il Disprezzo ( A Ghost at Noon or Contempt ) filmed by Jean-Luc Godard as Le Mépris ( Contempt ) (1963), and La Ciociara filmed by Vittorio de Sica as Two Women (1960). In 1960, he published one of his most famous novels, La noia ( The Empty Canvas ), the story of the troubled sexual relationship between a young, rich painter striving to find sense in his life and an easygoing girl, in Rome. It won the Viareggio Prize and was filmed by Damiano Damiani in 1962. An adaptation of the book is the basis of Cedric Kahn's the film L'ennui ("The Ennui") (1998). In 1960, Vittorio De Sica cinematically adapted La ciociara with Sophia Loren; Jean- Luc Godard filmed Il disprezzo ( Contempt ) (1963); and Francesco Maselli filmed Gli indifferenti (1964). -

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

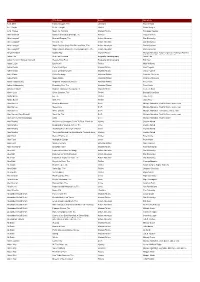

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Djuna Barnes's Bewildering Corpus. by Daniela Caselli. Burlington, VT

Book Reviews Improper Modernism: Djuna Barnes’s Bewildering Corpus. By Daniela Caselli. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009. x + 290 pp. $114.95 cloth. Modernist Articulations: A Cultural Study of Djuna Barnes, Mina Loy, and Gertrude Stein. By Alex Goody. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. xii + 242 pp. $75.00 cloth. TextWkg.indd 153 1/4/11 3:35:48 PM 154 THE SPACE BETWEEN Djuna Barnes’ Consuming Fictions. By Diane Warren. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008. xviii + 188 pp. $99.95 cloth. It is something of a scandal that so many people read Nightwood, a text that used to be so scandalous. For much of the twentieth century, the obscurity of Djuna Barnes’s novel was considered to be a central part of its appeal. To read or recommend it was to participate in a subversive or subcultural tradition, an alternative modernism that signified variouslylesbian , queer, avant-garde. Within the expanded field of recent modernist scholarship, however, Barnes’s unread masterpiece is now simply a masterpiece, one of the usual suspects on conference programs and syllabi. Those of us who remain invested in Barnes’s obscurity, however, can take comfort in the fact that, over the course of her long life and comparatively short career, Barnes produced an unruly body of work that is unlikely to be canonized. Indeed, Barnes’s reputation has changed: once treated as one of modern- ism’s interesting background figures, fodder to fill out the footnotes of her more famous male colleagues, she has now become instead a single-work author, a one-hit wonder. And no wonder; the rest of her oeuvre is made up of journalism, a Rabelaisian grab-bag of a novel, seemingly slight poems and stories, a Jacobean revenge drama, and an alphabetic bestiary.