Locally Calibrated Wave Hindcasts in the Estonian Coastal Sea in 1966–2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Currents and Waves in the Northern Gulf of Riga

doi:10.5697/oc.54-3.421 Currents and waves OCEANOLOGIA, 54 (3), 2012. in the northern Gulf of pp. 421–447. C Copyright by Riga: measurement and Polish Academy of Sciences, * Institute of Oceanology, long-term hindcast 2012. KEYWORDS Hydrodynamic modelling Water exchange Wave hindcast Wind climate RDCP Baltic Sea Ulo¨ Suursaar⋆ Tiit Kullas Robert Aps Estonian Marine Institute, University of Tartu, M¨aealuse 14, EE–12618 Tallinn, Estonia; e-mail: [email protected] ⋆corresponding author Received 27 February 2012, revised 19 April 2012, accepted 30 April 2012. Abstract Based on measurements of waves and currents obtained for a period of 302 days with a bottom-mounted RDCP (Recording Doppler Current Profiler) at two differently exposed locations, a model for significant wave height was calibrated separately for those locations; in addition, the Gulf of Riga-V¨ainameri 2D model was validated, and the hydrodynamic conditions were studied. Using wind forcing data from the Kihnu meteorological station, a set of current, water exchange and wave hindcasts were obtained for the period 1966–2011. Current patterns in the Gulf and in the straits were wind-dependent with characteristic wind switch directions. The Matsi coast was prone to upwelling in persistent northerly wind conditions. During the * The study was supported by the Estonian target financed project 0104s08, the Estonian Science Foundation grant No 8980 and by the EstKliima project of the European Regional Fund programme No 3.2.0802.11-0043. The complete text of the paper is available at http://www.iopan.gda.pl/oceanologia/ 422 U.¨ Suursaar, T. Kullas, R. -

A Study of Hydrodynamic and Coastal Geomorphic Processes in Küdema Bay, the Baltic Sea

Coastal Engineering 187 A study of hydrodynamic and coastal geomorphic processes in Küdema Bay, the Baltic Sea Ü. Suursaar1, H. Tõnisson2, T. Kullas1, K. Orviku3, A. Kont2, R. Rivis2 & M. Otsmann1 1Estonian Marine Institute, University of Tartu, Estonia 2Instititute of Ecology, Tallinn Pedagogical University, Estonia 3Merin Ltd., Estonia Abstract The aim of the paper is to analyze relationships between hydrodynamic and geomorphic processes in a small bay in the West-Estonian Archipelago. The area consists of a Silurian limestone cliff exposed to storm activity, and a dependent accumulative distal spit consisting of gravel and pebble. Changes in shoreline position have been investigated on the basis of large-scale maps, aerial photographs, topographic surveys and field measurements using GPS. Waves and currents were investigated using a Recording Doppler Current Profiler RDCP-600 deployed into Küdema Bay in June 2004 and the rough hydrodynamic situation was simulated using hydrodynamic and wave models. The main hydrodynamic patterns were revealed and their dependences on different meteorological scenarios were analyzed. It was found that due to exposure to prevailing winds (and waves induced by the longest possible fetch for the location), the spit elongates with an average rate of 14 m/year. Major changes take place during storms. Vitalization of shore processes is anticipated due to ongoing changes in the regional wind climate above the Baltic Sea. Keywords: shoreline changes, currents, waves, sea level, hydrodynamic models. 1 Introduction Estonia has a relatively long and strongly indented shoreline (3794 km; Fig. 1), therefore the knowledge of coastal processes is of large importance for WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 78, © 2005 WIT Press www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3509 (on-line) 188 Coastal Engineering sustainable development and management of the coastal zone. -

Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 80 (2008) 31–41

Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 80 (2008) 31–41 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecss Field observations on hydrodynamic and coastal geomorphic processes off Harilaid Peninsula (Baltic Sea) in winter and spring 2006–2007 U¨ . Suursaar a,*, J. Jaagus b,A.Kontc, R. Rivis c,H.To˜nisson c a Estonian Marine Institute, University of Tartu, Ma¨ealuse 10a, Tallinn 12618, Estonia b Institute of Geography, University of Tartu, Vanemuise 46, Tartu 51014, Estonia c Institute of Ecology, Tallinn University, Narva 25, Tallinn 10120, Estonia article info abstract Article history: Investigations of multi-layer current regime, variations in sea level and wave parameters using a bottom- Received 30 April 2008 mounted RDCP (Recording Doppler Current Profiler) during 20 December 2006–23 May 2007 were Accepted 5 July 2008 integrated with surveys on changes of shorelines and contours of beach ridges at nearby Harilaid Available online 18 July 2008 Peninsula (Saaremaa Island). A W-storm with a maximum average wind speed of 23 m sÀ1 occurred on 14–15 January with an accompanying sea level rise of at least 100 cm and a significant wave height of Keywords: 3.2 m at the 14 m deep RDCP mooring site. It appeared that in practically tideless Estonian coastal waters, sea level Doppler-based ‘‘vertical velocity’’ measurements reflect mainly site-dependent equilibrium between currents waves resuspension and sedimentation. The mooring site, 1.5 km off the Kelba Spit of Harilaid, was located in vertical fluxes the accumulation zone, where downward fluxes dominated and fine sand settled. -

Saare MAAKONNA Loodusväärtused Saare MAAKONNA Loodusväärtused 2 3

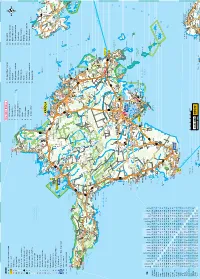

SAARE MAAKONNA loodusväärtused SAARE MAAKONNA loodusväärtused 2 3 SISUKORD KAITSEALAD ................... 8 Odalätsi maastikukaitseala ....... 27 Vilsandi rahvuspark ............. 9 Panga maastikukaitseala ......... 27 Abruka looduskaitseala .......... 10 Üügu maastikukaitseala ......... 28 Laidevahe looduskaitseala ........ 11 HOIUALAD .................... 30 Liiva-Putla looduskaitseala ....... 12 Karala-Pilguse hoiuala ........... 31 Linnulaht .................... 13 Karujärve hoiuala .............. 31 Loode tammik ................ 14 Väikese väina hoiuala ........... 33 Rahuste looduskaitseala ......... 15 Viidumäe looduskaitseala ........ 16 KAITSEALUSED PARGID ........... 34 Viieristi looduskaitseala. 17 Kuressaare lossipark ............ 34 Järve luidete maastikukaitseala .... 20 Mihkel Ranna dendraarium ....... 34 Kaali maastikukaitseala .......... 20 Mõntu park .................. 35 Kaugatoma-Lõo maastikukaitseala .. 21 Pädaste park ................. 35 Kaart ....................... 22 ÜksikobjEKTID ................ 36 Kesselaiu maastikukaitseala ...... 25 Põlispuud ................... 36 Koigi maastikukaitseala .......... 25 Rändrahnud .................. 40 KAITSTAVATE LOODUSOBJEKTIDE VALITSEJA Keskkonnaamet Hiiu-Lääne-Saare regioon Tallinna 22, 93819 Kuressaare tel 452 7777 [email protected] www.keskkonnaamet.ee KAITSTAVATE LOODUSOBJEKTIDE KÜLASTUSE KORRALDAJA RMK loodushoiuosakond Viljandi mnt. 18b, 11216 Tallinn [email protected] www.rmk.ee Koostaja: Maris Sepp Trükise valmimisele aitasid kaasa: Kadri Paomees, Rein Nellis, Veljo -

Rmk Annual Report 2014

RMK ANNUAL REPORT 2014 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 3 ADDRESS BY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD 32-39 ACTIVITIES IN NATURE AND NATURE EDUCATION GROWING FOREST BENEFITS 3 POSSIBILITIES FOR MOVING IN NATURE 34 5 TEN FACTS ABOUT RMK 5 NATURE EDUCATION 36 SAGADI FOREST CENTRE 37 6-11 ABOUT THE ORGANISATION ELISTVERE ANIMAL PARK 38 NATURE CAMERA 38 ALL OVER ESTONIA 8 CHRISTMAS TREES 39 EMPLOYEES 9 HERITAGE CULTURE 39 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 10 COOPERATION PROJECTS 11 40-45 RESEARCH WORK 12-23 FOREST MANAGEMENT APPLIED RESEARCH PROJECTS 42 USE OF RESEARCH RESULTS 44 FOREST LAND OVERVIEW 14 SCHOLARSHIPS 45 CUTTING WORKS 15 FOREST RENEWAL 16 AFFORESTATION OF QUARRIES 18 46-51 FINANCIAL SUMMARY TIMBER MARKETING 18 FOREST IMPROVEMENT 20 BALANCE SHEET 48 WASTE COLLECTION 22 INCOME STATEMENT 50 FOREST FIRES 22 AUDITOR’S REPORT 51 HUNTING 23 24-31 NATURE PROTECTION DIVISION OF STATE FOREST 26 PROTECTED AREAS 26 SPECIES UNDER PROTECTION 27 KEY BIOTOPES 28 BIODIVERSITY 28 NATURE PROTECTION WORKS 29 PÕLULA FISH FARM 31 2 Address by the Chairman of the Board GROWING FOREST BENEFITS Aigar Kallas Chairman of the Management Board of RMK The RMK Development Plan 2015-2020 was laid be certain that Estonia’s only renewable natural down in 2014. The overall idea of the six strategic resource would be used wisely for the benefit of goals established with the Development Plan is the society of both today and tomorrow, and that that the forest, land and diverse natural values natural diversity would be preserved, both in the entrusted to RMK must bring greater and more di- protected as well as the managed forest. -

Eestimaa Looduse Fond Vilsandi Rahvuspargi Kaitsekorralduskava

ELF-i poolt Keskkonnaametile üle antud kinnitamata versioon Eestimaa Looduse Fond Vilsandi rahvuspargi kaitsekorralduskava aastateks 2011-2020 Liis Kuresoo ja Kaupo Kohv Tartu-Vilsandi 2010 ELF-i poolt Keskkonnaametile üle antud kinnitamata versioon SISUKORD Sissejuhatus ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Vilsandi rahvuspargi iseloomustus ......................................................................................... 8 1.1 Vilsandi rahvuspargi asend .......................................................................................... 8 1.2 Vilsandi rahvuspargi geomorfoloogiline ja bioloogiline iseloomustus ....................... 8 1.3 Vilsandi rahvuspargi kaitse-eesmärk, kaitsekord ja rahvusvaheline staatus................ 8 1.4 Maakasutus ja maaomand ............................................................................................ 9 1.5 Huvigrupid ................................................................................................................. 13 1.6 Vilsandi rahvuspargi visioon ..................................................................................... 16 2 Väärtused ja kaitse-eesmärgid .............................................................................................. 17 Elustik ........................................................................................................................................... 17 2.1 Linnustik ................................................................................................................... -

V Ä I N a M E

LEGEND Ring ümber Hiiumaa 9. Hiiumaa Militaarmuuseum 19. Kuriste kirik Turismiinfokeskus; turismiinfopunkt 1. Põlise leppe kivid 10. Mihkli talumuuseum 20. Elamuskeskus Tuuletorn Sadam; lennujaam Tahkuna nina Tahkuna 2. Pühalepa kirik 11. Reigi kirik 21. Käina kiriku varemed Haigla; apteek looduskaitseala 14 3. Suuremõisa loss 12. Kõrgessaare – Viskoosa 22. Orjaku linnuvaatlustorn Kirik; õigeusukirik Tahkuna 4. Soera talumuuseum ja Mõis; kalmistu 13. Kõpu tuletorn 23. Orjaku sadam kivimitemaja Huvitav hoone; linnuse varemed 14. Ristna tuletorn 24. Kassari muuseum 5. Kärdla Mälestusmärk: sündmusele; isikule 15. Kalana 25. Sääretirp Tahkuna ps Lehtma 6. Kärdla sadam Skulptuur; arheoloogiline paik Meelste Suurjärv 16. Vanajõe org 26. Kassari kabel ja kabeliaed 7. Ristimägi RMK külastuskeskus; allikas 14 17. Sõru sadam ja muuseum 27. Vaemla villavabrik Kauste 8. Tahkuna tuletorn Austurgrunne Pinnavorm; looduslik huviväärsus 18. Emmaste kirik Meelste laht Park; üksik huvitav puu Hiiu madal 50 Tjuka (Näkimadalad) Suursäär Tõrvanina R Rändrahn; ilus vaade Kodeste ä l Mangu Kersleti b (Kärrslätt) y Metsaonn; lõkkekoht 82 l Malvaste a 50 Ta Tareste mka Kakralaid Borrby h 50 Mudaste res t Karavaniparkla; telkimiskoht te Ogandi o Kootsaare ps Matkarada; vaatetorn Sigala Saxby Tareste KÄRDLA Diby Vissulaid 50 Vormsi Tuulik; tuugen Fällarna Reigi laht Risti 80 välijõusaal Rälby Reigi Roograhu H Kroogi Hausma 50 Tuletorn; mobiilimast Ninalaid Posti Rootsi Kidaste Huitberg 50 Muuseum; kaitserajatis Ninaots a Kanapeeksi Heilu Förby 13 Linnumäe Suuremõisa -

FCE 39 Ebook

Folia Cryptog. Estonica, Fasc. 39: 1–2 (2002) Revisions of some lichens and lichenicolous fungi from Antarctica Vagn Alstrup Botanical Museum, University of Copenhagen, Gothersgade 130, DK-1123 Copenhagen K, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Arthonia subantarctica Øvstedal, Heterocarpon follmannii Dodge, Thelidiola eklundii Dodge and Thelidium minutum Dodge were found to be based on discordant elements of lichenized and lichenicolous fungi and are lectotypified on the lichenicolous fungi. The new combination Polycoccum follmannii (Dodge) Alstrup is made. Thelidiola Dodge is a synonym of Muellerella Hepp ex Müll. Arg., Catillaria cremea, Thelidiola eklundii and Thelidium minutum becomes synonyms of Carbonea vorticosa, Muellerella pygmaea and Muellerella lichenicola respectively. Kokkuvõte: Parandusi mõnede Antarktika samblike ja lihhenikoolsete seente taksonoomias. Arthonia subantarctica Øvstedal, Heterocarpon follmannii Dodge, Thelidiola eklundii Dodge ja Thelidium minutum Dodge leiti baseeruvat lihheniseerunud ja lihhenikoolsete seente ühtesobimatutel elementidel ja on lektotüpiseeritud lihhenikoolsete seentena. Esitatakse uus kombinatsioon Polycoccum follmannii (Dodge) Alstrup. Thelidiola Dodge on Muellerella Hepp ex Müll. Arg. sünonüüm; Catillaria cremea, Thelidiola eklundii ja Thelidium minutum sobivad vastavalt Carbonea vorticosa, Muellerella pygmaea ja Muellerella lichenicola sünonüümideks. INTRODUCTION The Antarctic lichens and lichenicolous fungi antarctica Øvstedal should accordingly be used have mostly been treated -

Wave Climate and Coastal Processes in the Osmussaar–Neugrund Region, Baltic Sea

Coastal Processes II 99 Wave climate and coastal processes in the Osmussaar–Neugrund region, Baltic Sea Ü. Suursaar1, R. Szava-Kovats2 & H. Tõnisson3 1Estonian Marine Institute, University of Tartu, Estonia 2Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, University of Tartu, Estonia 3Institute of Ecology, Tallinn University, Estonia Abstract The aim of the paper is to investigate hydrodynamic conditions in the Neugrund Bank area from ADCP measurements in 2009–2010, to present a local long-term wave hindcast and to study coastal formations around the Neugrund. Coastal geomorphic surveys have been carried out since 2004 and analysis has been performed of aerial photographs and old charts dating back to 1900. Both the in situ measurements of waves and currents, as well as the semi-empirical wave hindcast are focused on the area known as the Neugrund submarine impact structure, a 535 million-years-old meteorite crater. This crater is located in the Gulf of Finland, about 10 km from the shore of Estonia. The depth above the central plateau of the structure is 1–15 m, whereas the adjacent sea depth is 20– 40 m shoreward and about 60 m to the north. Limestone scarp and accumulative pebble-shingle shores dominate Osmussaar Island and Pakri Peninsula and are separated by the sandy beaches of Nõva and Keibu Bays. The Osmussaar scarp is slowly retreating on the north-western and northern side of the island, whereas the coastline is migrating seaward in the south as owing to formation of accumulative spits. The most rapid changes have occurred either during exceptionally strong single storms or in periods of increased cyclonic and wave activity, the last high phase of which occurred in 1980s–1990s. -

FCE 31 Ebook

Folia Cryptog. Estonica, Fasc. 31: 17 (1997) Additions and amendments to the list of Estonian bryophytes Leiti Kannukene1, Nele Ingerpuu2, Kai Vellak3 and Mare Leis3 1 Institute of Ecology, 2 Kevade St., EE0001 Tallinn, Estonia 2 Institute of Zoology and Botany, 181 Riia St., EE2400 Tartu, Estonia 3 Institute of Botany and Ecology, University of Tartu, 40 Lai St., EE2400 Tartu, Estonia Abstract: Investigations during last two years (19941996) have added 13 new species and 4 varieties to the list of Estonian bryophytes. Also, several new localities for 54 very rare and rare species and two varieties have been found. Eight species are no longer considered to be rare in Estonia and two must be excluded from the list of Estonian bryophytes due to misidentifications. Kokkuvõte: L. Kannukene, N. Ingerpuu, K. Vellak ja M. Leis. Täiendusi ja parandusi Eesti sammalde nimestikule. Viimase kahe aasta (19941996) uurimistööde tulemusel on Eesti sammalde nimestikule (510 liiki) lisandunud 13 uut liiki (Harpanthus flotovianus, Jungermannia subulata, Aloina rigida, Bartramia ithyphylla, Bryum arcticum, B. calophyllum, B. klingraeffi, Dichelyma capillaceum, Pohlia sphagnicola, Physcomitrium eurystomum, Racomitrium elongatum, Rhytidium rugosum, Tetraplodon mnio ides) ja neli uut varieteeti (Lophozia ventricosa var. silvicola, Aulacomnium palustre var. imbricatum, Dicranella schreberiana var. robusta, Schistidium rivulare var. rivualre). Üks uutest liikidest (Dichelyma capillaceum) kuulub Euroopa punase raamatu ohustatud liikide kategooriasse. On leitud uusi leiukohti 54 liigile ja kahele varieteedile haruldaste ja väga haruldaste taksonite seast. Harulduste hulgast on mitmete uute leiukohtade tõttu välja arvatud kaheksa liiki ning nimestikust valemäärangute tõttu kaks liiki (Orthotrichum tenellum ja Ditrichum heteromallum). INTRODUCTION The list of Estonian bryophytes (Ingerpuu et Co., Nigula Nature Reserve, in the north- al., 1994) contains 510 species, two hornworts ern part of forest sq. -

Shoreline Dynamics in Estonia Associated with Climate Change

TALLINNA PEDAGOOGIKAÜLIKOOLI LOODUSTEADUSTE DISSERTATSIOONID TALLINN PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY DISSERTATIONS ON NATURAL SCIENCES 9 SHORELINE DYNAMICS IN ESTONIA ASSOCIATED WITH CLIMATE CHANGE Abstract REIMO RIVIS Tallinn 2005 2 Chair of Geoecology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Tallinn Pedagogical University, Estonia The dissertation accepted for commencement of the degree of Doctor philosophiae in Ecology on December, 10 2004 by the Doctoral Committee of Ecology of the Tallinn Pedagogical University Supervisors: Urve Ratas, Cand. Sci. (Geogr.), Researcher of the Institute of Ecology at Tallinn Pedagogical University; Are Kont, Cand. Sci. (Geogr.), Senior Researcher of the Institute of Ecology at Tallinn Pedagogical University. Opponent: Tiit Hang, PhD, Senior Researcher of the Institute of Geology at Tartu University The academic disputation on the dissertation will be held at the Tallinn Pedagogical University (Lecture Hall 223) Narva Road 25, Tallinn on January 21, 2005 at 11 a.m. The publication of this dissertation has been funded by Tallinn Pedagogical University. Trükitud: OÜ Vali Press Pajusi mnt 22 48104 Põltsamaa ISSN 1406-4383 (trükis) ISBN 9985-58-359-0 ISSN 1736-0749 (on-line, PDF) ISBN 9985-58-360-4 (on-line, PDF) © Reimo Rivis 2005 3 CONTENTS LIST OF ORIGINAL PUBLICATIONS...................................................................................................4 PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................5 -

Norwegian Journal of Geography Restitution of Agricultural Land In

This article was downloaded by: [Holt-Jensen, Arild][Universitetsbiblioteket i Bergen] On: 16 September 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 907435713] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713735796 Restitution of agricultural land in Estonia: Consequences for landscape development and production Arild Holt-Jensen; Garri Raagmaa Online publication date: 15 September 2010 To cite this Article Holt-Jensen, Arild and Raagmaa, Garri(2010) 'Restitution of agricultural land in Estonia: Consequences for landscape development and production', Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography, 64: 3, 129 — 141 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00291951.2010.502443 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2010.502443 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.