Potential Map for the Installation of Concentrated Solar Power Towers in Chile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Energies for the 21St Century

THE collEcTion 1 w The atom 2 w Radioactivity 3 w Radiation and man 4 w Energy 5 w Nuclear energy: fusion and fission 6 w How a nuclear reactor works 7 w The nuclear fuel cycle 8 w Microelectronics 9 w The laser: a concentrate of light 10 w Medical imaging 11 w Nuclear astrophysics 12 w Hydrogen 13 w The Sun 14 w Radioactive waste 15 w The climate 16 w Numerical simulation 17 w Earthquakes 18 w The nanoworld 19 w Energies for the 21st century © French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission, 2010 Communication Division Head Office 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette cedex - www.cea.fr ISSN 1637-5408. w Low-carbon energies for a sustainable future FROM RESEARCH TO INDUSTRY 19 w energies for the 21st century InnovatIng for nuclear energy DomestIcatIng solar power BIofuel proDuctIon DevelopIng BatterIes anD fuel cells thermonuclear fusIon 2 w contents century © Jack Star/PhotoLink st Innovating for nuclear ENERgY 6 The beginnings of nuclear energy in France 7 The third generation 8 Generation IV: new concepts 10 DEveloping batteries and fuel cells 25 Domesticating solar Lithium-ion batteries 26 pOwer 13 A different application for Thermal solar power 15 each battery 27 Photovoltaic solar power 16 Hydrogen: an energy carrier 29 Concentrated solar power 19 Thermonuclear fusion 31 BIOFUEL production 20 Tokamak research 33 Biomass 21 ITER project 34 Energies for the 21 2nd generation biofuels 22 Designed and produced by: MAYA press - Printed by: Pure Impression - Cover photo: © Jack Star/PhotoLink - Illustrations : YUVANOE - 09/2010 Low-carbon energies for a sustainable future 19 w Energies for the 21st century w> IntroIntroDuctIon 3 The depletion of fossil resources and global warming are encoura- ging the development of research into new energy technologies (on the left, Zoé, France’s first nuclear reactor, on the right, the national institute for solar power). -

Australian Rooftop Solar Subsidy 2019 Outlook

Australian Rooftop Solar Subsidy 2019 Outlook 18 February 2019 © Demand Manager Pty Ltd PO Box Q1251 QVB Post Office NSW 1230 AFSL 474395 www.demandmanager.com.au The material in this report is provided for general information and educative purposes only. The content does not investment advice or recommendations and should not be relied upon as such. Appropriate professional advice should be obtained for any investment decisions. While every care has been taken in the preparation of this material, Demand Manager cannot accept responsibility for any errors, including those caused by negligence, in the material. Demand Manager makes no statements, representations or warranties about the accuracy or completeness of the information and you should not rely on it. You are advised to make your own independent inquiries regarding the accuracy of any information provided in this report. Executive Summary The SRES is one half of the Australian Government’s Renewable Energy Target and offers upfront rebates to consumers installing small-scale solar power systems. This cost is borne by all electricity consumers as a levy charged per kWh of consumption. Solar power installations continue to accelerate, driven by: o Cheaper component costs; o Increasing adoption in the commercial sector; o Policy drivers in Victoria and South Australia and soon NSW In early 2018, Demand Manager forecast the cost of the SRES in 2018 to total $1.3 billion. Actual cost of the SRES in 2018 was in the order of $1.2 billion1. In our LOW case scenario, Demand Manager forecasts the economy-wide cost of the SRES to increase 30% in 2019 to $1.56 billion. -

Fulfilling the Promise of Concentrating Solar Power Low-Cost Incentives Can Spur Innovation in the Solar Market

AGENCY/PHOTOGRAPHER ASSOCIATED PRESS ASSOCIATED Fulfilling the Promise of Concentrating Solar Power Low-Cost Incentives Can Spur Innovation in the Solar Market By Sean Pool and John Dos Passos Coggin June 2013 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Fulfilling the Promise of Concentrating Solar Power Low-Cost Incentives Can Spur Innovation in the Solar Market By Sean Pool and John Dos Passos Coggin May 2013 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 3 6 reasons to support concentrating solar power 5 Concentrating solar power is a proven zero-carbon technology with high growth potential 6 Concentrating solar power can be used for baseload power 7 Concentrating solar power has few impacts on natural resources 8 Concentrating solar power creates jobs Concentrating solar power is low-cost electricity 9 Concentrating solar power is carbon-free electricity on a budget 11 Market and regulatory challenges to innovation and deployment of CSP technology 13 Low-cost policy solutions to reduce risk, promote investment, and drive innovation 14 Existing policy framework 15 Policy reforms to reduce risk and the cost of capital 17 Establish an independent clean energy deployment bank 18 Implement CLEAN contracts or feed-in tariffs Reinstate the Department of Energy’s Loan Guarantee Program 19 Price carbon Policy reforms to streamline regulation and tax treatment 20 Tax reform for capital-intensive clean energy technologies Guarantee transmission-grid connection for solar projects 21 Stabilize and monetize existing tax incentives 22 Further streamline regulatory approval by creating an interagency one-stop shop for solar power 23 Regulatory transparency 24 Conclusion 26 About the authors 27 Endnotes Introduction and summary Concentrating solar power—also known as concentrated solar power, concen- trated solar thermal, and CSP—is a cost-effective way to produce electricity while reducing our dependence on foreign oil, improving domestic energy-price stabil- ity, reducing carbon emissions, cleaning our air, promoting economic growth, and creating jobs. -

Analysis of Solar Community Energy Storage for Supporting Hawaii's 100% Renewable Energy Goals Erin Takata [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-19-2017 Analysis of Solar Community Energy Storage for Supporting Hawaii's 100% Renewable Energy Goals Erin Takata [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Oil, Gas, and Energy Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Takata, Erin, "Analysis of Solar Community Energy Storage for Supporting Hawaii's 100% Renewable Energy Goals" (2017). Master's Projects and Capstones. 544. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/544 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This Master's Project Analysis of Solar Community Energy Storage for Supporting Hawaii’s 100% Renewable Energy Goals by Erin Takata is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Science in Environmental Management at the University of San Francisco Submitted: Received: ...................................……….. ................................…………. -

Loddon Mallee Renewable Energy Roadmap

Loddon Mallee Region Renewable Energy Roadmap Loddon Mallee Renewable Energy Roadmap Foreword On behalf of the Victorian Government, I am pleased to present the Victorian Regional Renewable Energy Roadmaps. As we transition to cleaner energy with new opportunities for jobs and greater security of supply, we are looking to empower communities, accelerate renewable energy and build a more sustainable and prosperous state. Victoria is leading the way to meet the challenges of climate change by enshrining our Victorian Renewable Energy Targets (VRET) into law: 25 per cent by 2020, rising to 40 per cent by 2025 and 50 per cent by 2030. Achieving the 2030 target is expected to boost the Victorian economy by $5.8 billion - driving metro, regional and rural industry and supply chain development. It will create around 4,000 full time jobs a year and cut power costs. It will also give the renewable energy sector the confidence it needs to invest in renewable projects and help Victorians take control of their energy needs. Communities across Barwon South West, Gippsland, Grampians and Loddon Mallee have been involved in discussions to help define how Victoria transitions to a renewable energy economy. These Roadmaps articulate our regional communities’ vision for a renewable energy future, identify opportunities to attract investment and better understand their community’s engagement and capacity to transition to renewable energy. Each Roadmap has developed individual regional renewable energy strategies to provide intelligence to business, industry and communities seeking to establish or expand new energy technology development, manufacturing or renewable energy generation in Victoria. The scale of change will be significant, but so will the opportunities. -

Concentrating Solar Power: Energy from Mirrors

DOE/GO-102001-1147 FS 128 March 2001 Concentrating Solar Power: Energy from Mirrors Mirror mirror on the wall, what's the The southwestern United States is focus- greatest energy source of all? The sun. ing on concentrating solar energy because Enough energy from the sun falls on the it's one of the world's best areas for sun- Earth everyday to power our homes and light. The Southwest receives up to twice businesses for almost 30 years. Yet we've the sunlight as other regions in the coun- only just begun to tap its potential. You try. This abundance of solar energy makes may have heard about solar electric power concentrating solar power plants an attrac- to light homes or solar thermal power tive alternative to traditional power plants, used to heat water, but did you know there which burn polluting fossil fuels such as is such a thing as solar thermal-electric oil and coal. Fossil fuels also must be power? Electric utility companies are continually purchased and refined to use. using mirrors to concentrate heat from the sun to produce environmentally friendly Unlike traditional power plants, concen- electricity for cities, especially in the trating solar power systems provide an southwestern United States. environmentally benign source of energy, produce virtually no emissions, and con- Photo by Hugh Reilly, Sandia National Laboratories/PIX02186 Photo by Hugh Reilly, This concentrating solar power tower system — known as Solar Two — near Barstow, California, is the world’s largest central receiver plant. This document was produced for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), a DOE national laboratory. -

Recent Developments in Heat Transfer Fluids Used for Solar

enewa f R bl o e ls E a n t e n r e g Journal of y m a a n d d n u A Srivastva et al., J Fundam Renewable Energy Appl 2015, 5:6 F p f p Fundamentals of Renewable Energy o l i l ISSN: 2090-4541c a a n t r i DOI: 10.4172/2090-4541.1000189 o u n o s J and Applications Review Article Open Access Recent Developments in Heat Transfer Fluids Used for Solar Thermal Energy Applications Umish Srivastva1*, RK Malhotra2 and SC Kaushik3 1Indian Oil Corporation Limited, RandD Centre, Faridabad, Haryana, India 2MREI, Faridabad, Haryana, India 3Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, New Delhi, India Abstract Solar thermal collectors are emerging as a prime mode of harnessing the solar radiations for generation of alternate energy. Heat transfer fluids (HTFs) are employed for transferring and utilizing the solar heat collected via solar thermal energy collectors. Solar thermal collectors are commonly categorized into low temperature collectors, medium temperature collectors and high temperature collectors. Low temperature solar collectors use phase changing refrigerants and water as heat transfer fluids. Degrading water quality in certain geographic locations and high freezing point is hampering its suitability and hence use of water-glycol mixtures as well as water-based nano fluids are gaining momentum in low temperature solar collector applications. Hydrocarbons like propane, pentane and butane are also used as refrigerants in many cases. HTFs used in medium temperature solar collectors include water, water- glycol mixtures – the emerging “green glycol” i.e., trimethylene glycol and also a whole range of naturally occurring hydrocarbon oils in various compositions such as aromatic oils, naphthenic oils and paraffinic oils in their increasing order of operating temperatures. -

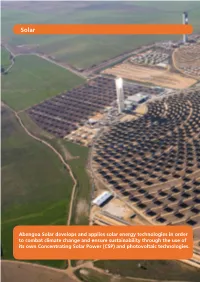

Abengoa Solar Develops and Applies Solar Energy Technologies in Order

Solar Abengoa Solar develops and applies solar energy technologies in order to combat climate change and ensure sustainability through the use of its own Concentrating Solar Power (CSP) and photovoltaic technologies. www.abengoasolar.com Solar International Presence Spain China U.S.A. Morocco Algeria 34 Activity Report 08 Solar Our business Abengoa is convinced that solar energy combines the characteristics needed to resolve, to a significant extent, our society’s need for clean and efficient energy sources. Each year, the sun casts down on the earth an amount of energy that surpasses the energy needs of our planet many times over, and there are proven commercial technologies available today with the capability of harnessing this energy in an efficient way. Abengoa Solar’s mission is to contribute to meeting an increasingly higher percentage of our society’s energy needs through solar- based energy. To this end, Abengoa Solar works with the two chief solar technologies in existence today. First, it employs Concentrating Solar Power (CSP) technology in capturing the direct radiation from the sun to generate steam and drive a conventional turbine or to use this energy directly in industrial processes, usually in major electrical power grid-connected plants. Secondly, Abengoa Solar works with photovoltaic technologies that employ the sun’s energy for direct electrical power generation, thanks to the use of materials based on the so-called photovoltaic effect. Abengoa Solar works with these technologies in four basic lines of activity. The first encompasses promotion, construction and operation of CSP plants, Abengoa Solar currently designs, builds and operates efficient and reliable central receiver systems (tower and heliostats) and storage or non-storage-equipped parabolic trough collectors, as well as customized industrial installations for producing heat and electricity. -

Comparison Between Concentrated Solar Power and Gas-Based Generation in Terms of Economic and Flexibility-Related Aspects in Chile

energies Article Comparison between Concentrated Solar Power and Gas-Based Generation in Terms of Economic and Flexibility-Related Aspects in Chile Catalina Hernández Moris 1 , Maria Teresa Cerda Guevara 1,* , Alois Salmon 1 and Alvaro Lorca 2 1 Fraunhofer Chile Research Foundation, Santiago 7820436, Chile; [email protected] (C.H.M.); [email protected] (A.S.) 2 Department of Electrical Engineering, Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, UC Energy Research Center, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago 7820436, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The energy sector in Chile demands a significant increase in renewable energy sources in the near future, and concentrated solar power (CSP) technologies are becoming increasingly competitive as compared to natural gas plants. Motivated by this, this paper presents a comparison between solar technologies such as hybrid plants and natural gas-based thermal technologies, as both technologies share several characteristics that are comparable and beneficial for the power grid. This comparison is made from an economic point of view using the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) metric and in terms of the systemic benefits related to flexibility, which is very much required due to the current decarbonization scenario of Chile’s energy matrix. The results show that the LCOE of the four hybrid plant models studied is lower than the LCOE of the gas plant. A solar hybrid plant configuration composed of a photovoltaic and solar tower plant (STP) with 13 h of storage Citation: Hernández Moris, C.; and without generation restrictions has an LCOE 53 USD/MWh, while the natural gas technology Cerda Guevara, M.T.; Salmon, A.; Lorca, Á.G. -

Desert Visions

erts in just six hours could power all of cilitator, encouraging governments and humankind for one year. Knies started the funders to take on solar and wind power Trans-Mediterranean Renewable Energy projects. One of its ¿ rst reference proj- Corporation (TREC), which developed ects will be a 500-MW solar power plant the Desertec concept with scientists from developed in cooperation with the Mo- the German Aerospace Center. TREC be- roccan Agency for Solar Energy (MA- came the Desertec Foundation in 2009, SEN). The plant will use a combination and now Knies serves as chair of the su- of technologies: 400 MW of concentrated pervisory board. solar power (CSP) and 100 MW of pho- Desertec proponents see the initiative tovoltaics (PV). Eighty percent of the as a “win-win” scenario, with both prac- electricity generated will be exported to tical and idealistic bene¿ ts. European Europe, carried by the transmission line countries would get additional sources of now used to ferry electricity in the other Initiative Regional power to ful¿ l their goals for transition- direction from Spain. • Desert ing from fossil fuels to renewable elec- Dii is also working with the utility tricity. The MENA countries would gain company STEG Energie Renouvelable visions sources of sustainable power to support to examine the feasibility of building the needs of their growing populations, large-scale solar and wind projects and Corinna Wu as well as a valuable product for export. transmission lines in Tunisia. Egypt The economic stimulus would create jobs and Algeria are also talking with Dii to on both sides of the Mediterranean, and ¿ nd avenues of cooperation, according ater may be scarce in the Sa- the sharing of electricity across the grid to van Son. -

A Heliostat Field Control System

A Heliostat Field Control System by Karel Johan Malan Dissertation presented for the degree of Master of Engineering in the Faculty of Engineering at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Mr Paul Gauché Co-supervisor: Mr Johann Treurnicht April 2014 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: ……………………………. Copyright © 2014 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract The ability of concentrating solar power (CSP) to efficiently store large amounts of energy sets it apart from other renewable energy technologies. However, cost reduction and improved efficiency is required for it to become more economically viable. Significant cost reduction opportunities exist, especially for central receiver system (CRS) technology where the heliostat field makes up 40 to 50 per cent of the total capital expenditure. CRS plants use heliostats to reflect sunlight onto a central receiver. Heliostats with high tracking accuracy are required to realize high solar concentration ratios. This enables high working temperatures for efficient energy conversion. Tracking errors occur mainly due to heliostat manufacturing-, installation- and alignment tolerances, but high tolerance requirements generally increase cost. A way is therefore needed to improve tracking accuracy without increasing tolerance requirements. The primary objective of this project is to develop a heliostat field control system within the context of a 5MWe CRS pilot plant. -

Concentrating Solar Power Tower: Latest Status 3 Report and Survey of Development Trends

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 17 November 2017 doi:10.20944/preprints201710.0027.v2 1 Review 2 Concentrating Solar Power Tower: Latest Status 3 Report and Survey of Development Trends 4 Albert Boretti 1,*, Stefania Castelletto 2 and Sarim Al-Zubaidy 3 5 1 Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (MAE), Benjamin M. Statler College of 6 Engineering and Mineral Resources, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506, United States, 7 [email protected]; [email protected] 8 2 School of Engineering, RMIT University, Bundoora, VIC 3083, Australia; [email protected] 9 3 The University of Trinidad and Tobago, Trinidad and Tobago; [email protected] 10 * Correspondence: [email protected]; [email protected] 11 Abstract: The paper examines design and operating data of current concentrated solar power (CSP) 12 solar tower (ST) plants. The study includes CSP with or without boost by combustion of natural gas 13 (NG), and with or without thermal energy storage (TES). The latest, actual specific costs per 14 installed capacity are very high, 6085 $/kW for Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System (ISEGS) 15 with no TES, and 9227 $/kW for Crescent Dunes with TES. The actual production of electricity is 16 very low and much less than the expected. The actual capacity factors are 22% for ISEGS, despite 17 combustion of a significant amount of NG largely exceeding the planned values, and 13% for 18 Crescent Dunes. The design values were 33% and 52%. The study then reviews the proposed 19 technology updates to produce better ratio of solar field power to electric power, better capacity 20 factor, better matching of production and demand, lower plant’s cost, improved reliability and 21 increased life span of plant’s components.