Official Naming in Hå, Klepp and Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin Lawrence W

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications Library Faculty January 2013 The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin Lawrence W. Onsager Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/library-pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Onsager, Lawrence W., "The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin" (2013). Faculty Publications. Paper 25. http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/library-pubs/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Faculty at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ANASON FAMILY IN ROGALAND COUNTY, NORWAY AND JUNEAU COUNTY, WISCONSIN BY LAWRENCE W. ONSAGER THE LEMONWEIR VALLEY PRESS Berrien Springs, Michigan and Mauston, Wisconsin 2013 ANASON FAMILY INTRODUCTION The Anason family has its roots in Rogaland County, in western Norway. Western Norway is the area which had the greatest emigration to the United States. The County of Rogaland, formerly named Stavanger, lies at Norway’s southwestern tip, with the North Sea washing its fjords, beaches and islands. The name Rogaland means “the land of the Ryger,” an old Germanic tribe. The Ryger tribe is believed to have settled there 2,000 years ago. The meaning of the tribal name is uncertain. Rogaland was called Rygiafylke in the Viking age. The earliest known members of the Anason family came from a region of Rogaland that has since become part of Vest-Agder County. -

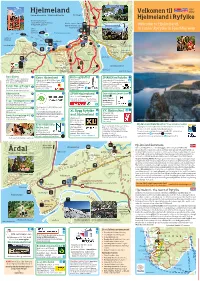

Hjelmeland 2021

Burmavegen 2021 Hjelmeland Nordbygda Velkomen til 2022 Kommunesenter / Municipal Centre Nordbygda Leite- Hjelmeland i Ryfylke Nesvik/Sand/Gullingen runden Gamle Hjelmelandsvågen Sauda/Røldal/Odda (Trolltunga) Verdas største Jærstol Haugesund/Bergen/Oslo Welcome to Hjelmeland, Bibliotek/informasjon/ Sæbø internet & turkart 1 Ombo/ in scenic Ryfylke in Fjord Norway Verdas største Jærstol Judaberg/ 25 Bygdamuseet Stavanger Våga-V Spinneriet Hjelmelandsvågen vegen 13 Sæbøvegen Judaberg/ P Stavanger Prestøyra P Hjelmen Puntsnes Sandetorjå r 8 9 e 11 s ta 4 3 g Hagalid/ Sandebukta Vågavegen a Hagalidvegen Sandbergvika 12 r 13 d 2 Skomakarnibbå 5 s Puntsnes 10 P 7 m a r k 6 a Vormedalen/ Haga- haugen Prestagarden Litle- Krofjellet Ritlandskrateret Vormedalsvegen Nasjonal turistveg Ryfylke Breidablikk hjelmen Sæbøhedlå 14 Hjelmen 15 Klungen TuntlandsvegenT 13 P Ramsbu Steinslandsvatnet Årdal/Tau/ Skule/Idrettsplass Hjelmen Sandsåsen rundt Liarneset Preikestolen Søre Puntsnes Røgelstad Røgelstadvegen KART: ELLEN JEPSON Stavanger Apal Sideri 1 Extra Hjelmeland 7 Kniv og Gaffel 10 SMAKEN av Ryfylke 13 Sæbøvegen 35, 4130 Hjelmeland Vågavegen 2, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 916 39 619 Vågavegen 44, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 454 32 941. www.apalsideri.no [email protected] Prisbelønna sider, eplemost Tlf 51 75 30 60. www.Coop.no/Extra Tlf 938 04 183. www.smakenavryfylke.no www.knivoggaffelas.no [email protected] Alt i daglegvarer – Catering – påsmurt/ Tango Hår og Terapi 2 post-i-butikk. Grocery Restaurant - Catering lunsj – selskapsmat. - Selskap. Sharing is Caring. 4130 Hjelmeland. Tlf 905 71 332 store – post office Pop up-kafé Hairdresser, beauty & personal care Hårsveisen 3 8 SPAR Hjelmeland 11 Den originale Jærstolen 14 c Sandetorjå, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 51 75 04 11. -

“Proud to Be Norwegian”

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY Travel In Your Neighborhood Norway’s most Contribute to beautiful stone Et skip er trygt i havnen, men det Amundsen’s Read more on page 9 er ikke det skip er bygget for. legacy – Ukjent Read more on page 13 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 124 No. 4 February 1, 2013 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidende $1.50 per copy News in brief Find more at blog.norway.com “Proud to be Norwegian” News Norway The Norwegian Government has decided to cancel all of commemorates Mayanmar’s debts to Norway, nearly NOK 3 billion, according the life of to Mayanmar’s own government. The so-called Paris Club of Norwegian creditor nations has agreed to reduce Mayanmar’s debts by master artist 50 per cent. Japan is cancelling Edvard Munch debts worth NOK 16.5 billion. Altogether NOK 33 billion of Mayanmar’s debts will be STAFF COMPILATION cancelled, according to an Norwegian American Weekly announcement by the country’s government. (Norway Post) On Jan. 23, HM King Harald and other prominent politicians Statistics and cultural leaders gathered at In 2012, the total river catch of Oslo City Hall to officially open salmon, sea trout and migratory the Munch 150 celebration. char amounted to 503 tons. This “Munch is one of our great is 57 tons, or 13 percent, more nation-builders. Along with author than in 2011. In addition, 91 tons Henrik Ibsen and composer Edvard of fish were caught and released. Grieg, Munch’s paintings lie at the The total catch consisted of core of our cultural foundation. -

Gården Øya, Øyaveien 48, Gnr./Bnr. 80/3, I Eigersund Kommune - Vedtak Om Fredning

SAKSBEHANDLER INNVALG STELEFON TELEFAKS Linn Brox +47 22 94 04 04 [email protected] VÅR REF. DERESREF. www.riksantikvaren.no 17/02077 - 5 17/9484 - 8 DERESDATO ARK. B - Bygninger VÅR DATO 223 (Egersund) Eigersund - Ro 02.10.2018 Se mottakerliste Gården Øya, Øyaveien 48, gnr./bnr. 80/3, i Eigersund kommune - vedtak om fredning Vi viser til tidligere utsendt fredningsforslag for gården Øya datert 22. mai 2018 som har vært på høring hos berørte parter og instanser. På grunnlag av dette fatter Riksantikvaren følgende vedtak: VEDTAK: Med hjemmel i lov om kulturminner av 9. juni 1978 nr. 50 § 15 og § 19 jf. § 22, freder Riksantikvaren gård en Øya , Øyaveien 48, gnr./bnr. 80/3, i Eigersund kommune. Omfanget av fredningen Fredningen etter § 15 omfatter følgende objekter: Våningshus, bygningsnummer: 169866678(Askeladden ID: 150191- 1) Fjøs, bygningsnummer 169866228(Askeladden ID: 150191- 2) Løe, bygningsnummer: 169866236(Askeladden ID: 150191- 3) Tun (Askeladden - ID: 150191- 7) Kvernhus , koordinat : 6523546N- 11224Ø (Askeladden ID: 150191- 4) Kanal , koordinat : 6523573N- 11120Ø (Askeladden -ID: 150191-6) Riksantikvaren - Direktoratet for kulturminneforvaltning A: 13392 Dronningensgate 13 • Pb. 1483 Vika. • 0116 Oslo • Tlf: 22 94 04 00 • www.ra.no 2 Den gamle veien , koordinat : 6523663N- 11179Ø, 6523795N- 11136Ø (Askeladden - ID: 150191- 8) Fredningen omfatter bygningenes eksteriør og interiør og inkluderer hovedelementer som konstruksjon, planløsning, materialbruk og overflateb ehandling og detaljer som vinduer, dører, gerikter, listverk og fast inventar. Et unntak fra dette er våningshuset der interiøret som helhet ikke inngår i fredningen, men innvendig kun omfatter konstruksjon, laftekasser og planløsning. Fredningen etter § 19 omfatter utmark og beiteområder . Fredningen etter § 19 er avmerket på kartet under. -

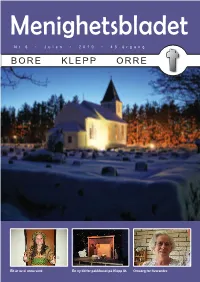

Bore Klepp Orre

Menighetsbladet Nr.6 • Julen • 2010 • 43.årgang BORE KLEPP ORRE Eit år av ei anna verd En ny tid for pakkhuset på Klepp St. Omsorg for hverandre KLEPP KYRKJELEGE FELLESRÅD KLEPP KYRKJEKONTOR Besøksadresse: Kleppvarden 2, 4352 Kleppe Postadresse: Postboks 101, 4358 Kleppe Telefon: 51 78 95 55 Telefaks: 51 78 95 50 e-post: [email protected] e-post Menighetsbladet: [email protected] Heimeside: www.klepp.kyrkja.no KONTORTIDER Måndag - torsdag: 08.30 - 14.30 Fredag: 08.30 - 12.30 Elles etter avtale Organ for Klepp Prestegjeld. Kjem ut 6 gonger i året. Frøyland og Orstad kyrkjekontor: Besøksadresse: Orstadbakken 33, 4355 Kvernaland Redaksjonskomité: Postadresse: Postboks 43, 4356 Kvernaland Telefon: 52 97 31 50 Einar Egeland Heimeside: www.minkirke.no/fok Anne Håkonsholm Arvid Hareland Kontortider: Ingunn D. Aandal - kontaktperson Tysdag og torsdag: 09.00-12.00 Bore kyrkje 51 42 22 52 Layout: Linda Aanestad Soknerådet, Nikolai Homme 51 42 00 77 900 53 744 Forsidefoto: Einar Egeland Frøyland og Orstad kyrkjelyd Trykk: Olsson as Soknerådet, Sigve Klakegg 51 48 75 83 900 21 677 Postadresse: Klepp kyrkje 51 42 16 39 Soknerådet, Svein Olav Nesse 51 42 34 86 920 22 874 Menighetsbladet - Postboks 101 Orre kyrkje 51 42 23 46 - 4358 Kleppe Soknerådet, Bjørn Borgen 51 42 86 94 900 19 534 TELEFONLISTE ANSATTE: - Telefon: 51 78 95 55 - e-post: Namn Direktenummer Privat Kyrkjeverge, Johannes Byberg Sr. 51 78 95 60 915 89 325 [email protected] Sekretær, Ingunn D. Aandal 51 78 95 59 924 19 934 Sekretær, Kari Haavardsholm 51 78 95 55 992 66 752 Bankgiro: 3290.07.02239 Sokneprest, Andreas Haarr 51 78 95 51 977 16 339 Neste nummer kjem ut 3. -

The Realisation of Traditional Local Dialectal Features in the Address Names of Two Western Norwegian Municipalities DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/4

Onoma 54 Journal of the International Council of Onomastic Sciences ISSN: 0078-463X; e-ISSN: 1783-1644 Journal homepage: https://onomajournal.org/ The realisation of traditional local dialectal features in the address names of two Western Norwegian municipalities DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/4 Wen Ge University of Iceland Sæmundargata 14 102 Reykjavík Iceland [email protected] To cite this article: Wen Ge. 2019. The realisation of traditional local dialectal features in the address names of two Western Norwegian municipalities. Onoma 54, 53–75. DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/4 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/4 © Onoma and the author. The realisation of traditional local dialectal features in the address names of two Western Norwegian municipalities Abstract: Norway is often seen as a dialect paradise: it is acceptable to use dialects in both private and public contexts. Does this high degree of dialect diversity and tolerance also apply to Norwegian place-names? In order to shed light on this question, I will examine address names in two former municipalities in Hardanger, a traditional Western Norwegian district, as for the degree of the visibility of a selection of the traditional local dialectal features. Features retained in the names will be evaluated in terms of to what extent they are permitted by the current place-name regulations, so as to see whether dialect diversity and tolerance apply to Norwegian place-names. Keywords: Place-name standardisation, rural area, traditional dialect, Norway. 54 WEN GE La réalisation de caractéristiques dialectales traditionnelles et locales dans les noms d’adresses dans deux communautés dans l’ouest de la Norvège Résumé : La Norvège est souvent perçue comme un paradis des dialectes : leur emploi est universellement accepté dans les contextes même privés comme publiques. -

Joint Respiratory Emergency Room for Sandnes, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time and Hå

JOINT RESPIRATORY EMERGENCY ROOM FOR SANDNES, GJESDAL, KLEPP, TIME AND HÅ. Respiratory emergency room for Sandnes, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time and Hå: Weekdays at 08-15: For all five municipalities, the Sandnes emergency room receives telephone calls and patients with respiratory symptoms who need medical attention. Address: Brannstasjonsveien 2, 4312 Sandnes Weekdays at 15-23, weekends and holidays 08-23: For all five municipalities, the respiratory emergency room located at the premises of Klepp and Time emergency room receive telephone and patients with respiratory symptoms who need medical attention. Address: Olav Hålands veg 2, 4352 Kleppe Please do not show up without calling 116 117 first! Corona testing: You no longer need a doctor's referral to order a covid-19 test. However, it is important that you check the current criteria for testing before booking an appointment. You can order a corona test online at c19.no. Log in with electronic ID, provide contact information and state whether you are booking for yourself or for someone else. Once you have submitted the form, you will receive information about when and where to meet. You may experience getting an appointment as early as 45 minutes after booking. The waiting time depends on the current test capacity. Alternatively, you can call the emergency room to book an appointment. Daytime 08-15: Call 51 68 31 50 Afternoon, evening, and weekend: Call 51 42 99 99 Corona testing is performed at Kleppe. Please do not show up without an appointment. It is also important that you arrive precisely to the time you are allocated to avoid unnecessary queueing. -

SVR Brosjyre Kart

VERNEOMRÅDA I Setesdal vesthei, Ryfylkeheiane og Frafjordheiane (SVR) E 134 / Rv 13 Røldal Odda / Hardanger Odda / Hardanger Simlebu E 134 13 Røldal Haukeliseter HORDALAND Sandvasshytta E 134 Utåker Åkra ROGALAND Øvre Sand- HORDALAND Haukeli vatnbrakka TELEMARK Vågslid 520 13 Blomstølen Skånevik Breifonn Haukeligrend E 134 Kvanndalen Oslo SAUDA Holmevatn 9 Kvanndalen Storavassbu Holmevassåno VERNEOMRÅDET Fitjarnuten Etne Sauda Roaldkvam Sandvatnet Sæsvatn Løkjelsvatnhytta Saudasjøen Skaulen Nesflaten Varig verna Sloaros Breivatn Bjåen Mindre verneområdeVinje Svandalen n e VERNEOMRÅDAVERNEOVERNEOMRÅDADA I d forvalta av SVR r o Bleskestadmoen E 134 j Dyrskarnuten f a Ferdselsrestriksjonar: d Maldal Hustveitsåta u Lislevatn NR Bråtveit ROGALAND Vidmyr NR Haugesund Sa Suldalsvatnet Olalihytta AUST-AGDER Lundane Heile året Hovden LVO Hylen Jonstøl Hovden Kalving VINDAFJORD (25. april–31. mai) Sandeid 520 Dyrskarnuten Snønuten Hartevatn 1604 TjørnbrotbuTjø b tb Trekk Hylsfjorden (15. april–20. mai) 46 Vinjarnuten 13 Kvilldal Vikedal Steinkilen Ropeid Suldalsosen Sand Saurdal Dyraheio Holmavatnet Urdevasskilen Turisthytter i SVR SULDAL Krossvatn Vindafjorden Vatnedalsvatnet Berdalen Statsskoghytter Grjotdalsneset Stranddalen Berdalsbu Fjellstyrehytter Breiavad Store Urvatn TOKKE 46 Sandsfjorden Sandsa Napen Blåbergåskilen Reinsvatnet Andre hytter Sandsavatnet 9 Marvik Øvre Moen Krokevasskvæven Vindafjorden Vatlandsvåg Lovraeid Oddatjørn- Vassdalstjørn Gullingen dammen Krokevasshytta BYKLE Førrevass- Godebu 13 dammen Byklestøylane Haugesund Hebnes -

Utbyggingspakke Jæren

SAKSFRAMLEGG Saksbehandlar: Målfrid Hannisdal Teigen Arkiv: 205 Arkivsaksnr.: 18/1855 - 47 Planlagt behandling: Formannskapet Kommunestyret UTBYGGINGSPAKKE JÆREN Bakgrunn for saka Kommunestyret gjorde i sak 65/18 eit prinsippvedtak om det vidare arbeidet med utbyggingspakke Jæren. Følgjande prinsipp vart vedteke: 1. Det skal arbeidast vidare med å etablera ei bompengefinansiert utbyggingspakke for kommunane Hå, Klepp og Time. 2. Prosjektet Fv. 505 Tverrforbindelsen Foss-Eikeland til E39 Bråstein blir overført frå Bymiljøpakken til Utbyggingspakke Jæren. Fram til neste høyringsrunde i kommunane skal overføring og finansiering vera avklart. 3. Inntektene for felles timesregel mellom Utbyggingspakke Jæren og Bymiljøpakken går til den bompengepakka der første passering skjer. 4. Premissar for Utbyggingspakken: a. Takstane blir identiske med takstane utanom rushperiodane i Bymiljøpakken b. Nullutsleppskøyretøy betaler 50 % av takstgruppe 1 c. Det blir eit passeringstak på 75 passeringar per månad d. Innkrevjingsperiode blir 15 år e. Det blir rabatt på 20 % ved bruk av bompengebrikke 5. Utbyggingspakke Jæren skal gje ”bedre framkommelighet for alle”. Midlane skal gå til etablering av nye vegar, utbetring av eksisterande vegar, gjennomføring av trafikksikringstiltak, etablering av gjennomgåande gang- og sykkelvegar, tiltak som betrar kollektivtilbodet og som legg til rette for «park and ride» mot Jærbanen. 6. Alternative traséval for Fv. 505 Tverrforbindelsen Foss-Eikeland til E39 Bråstein må hensynta rekreasjonsområdet tilknytta fossen/Figgjoelva slik at dette blir bevart i eit viktig utbyggingsområde. 7. Innkrevjingskost må vera betydeleg lågare enn det som er skissert, gjennom å vurdera forskjellige tekniske løysingar. 8. Totalfinansieringa bør vera kjent. 9. Moglegheit for etterskotsvis innkrevjing av bompengar, når vegen er ferdig bygd, vert vurdert/utgreia. 10. Klepp kommune bør vurdera ei ordning for å skåna dei småbarnsfamiliane som blir ramma urimeleg hardt av bompengane. -

GSM Network Design for Stavanger and Sandnes

GSM network design for Stavanger and Sandnes Jan Magne Tjensvold November 6, 2007 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Background 2 2.1 Geography and population . 2 2.2 Technology and equipment . 4 3 Calculations 4 3.1 Omni directional antenna . 4 3.2 Sectored antenna . 6 3.3 Voice channels . 6 3.4 Traffic density . 6 3.5 Cells . 7 3.6 Equipment . 8 4 Cost estimate 8 References 9 1 Introduction This report investigates the design of a GSM network for the cities of Sta- vanger and Sandnes in Norway. It provides a cost estimate of the required infrastructure in these two cities and for the highway connecting them. The estimate only includes equipment costs and not maintenance costs or other operational costs which would be needed to keep the network fully func- tional during its lifetime. It only includes the cost for the base transceiver stations (BTS), base station controllers (BSC) and the mobile switching center (MSC). 1 Figure 1: Map of Norway with the Figure 2: Rogaland county with location of Stavanger and Sandnes. the municipality of Stavanger in red and Sandnes in blue. 2 Background 2.1 Geography and population Stavanger and Sandnes is located in the county of Rogaland, Norway as seen by Figure 1 and 2. Statistics Norway (SSB) [1] provides maps showing the population density of an area. One such map of Stavanger and Sandnes has been used as the basis for drawing an outline of the urban areas in Figure 3 on the next page. SSB provided some vital statistics for the two municipalities which is shown in Table 1 on the following page. -

Iconic Hikes in Fjord Norway Photo: Helge Sunde Helge Photo

HIMAKÅNÅ PREIKESTOLEN LANGFOSS PHOTO: TERJE RAKKE TERJE PHOTO: DIFFERENT SPECTACULAR UNIQUE TROLLTUNGA ICONIC HIKES IN FJORD NORWAY PHOTO: HELGE SUNDE HELGE PHOTO: KJERAG TROLLPIKKEN Strandvik TROLLTUNGA Sundal Tyssedal Storebø Ænes 49 Gjerdmundshamn Odda TROLLTUNGA E39 Våge Ølve Bekkjarvik - A TOUGH CHALLENGE Tysnesøy Våge Rosendal 13 10-12 HOURS RETURN Onarheim 48 Skare 28 KILOMETERS (14 KM ONE WAY) / 1,200 METER ASCENT 49 E134 PHOTO: OUTDOORLIFENORWAY.COM PHOTO: DIFFICULTY LEVEL BLACK (EXPERT) Fitjar E134 Husnes Fjæra Trolltunga is one of the most spectacular scenic cliffs in Norway. It is situated in the high mountains, hovering 700 metres above lake Ringe- ICONIC Sunde LANGFOSS Håra dalsvatnet. The hike and the views are breathtaking. The hike is usually Rubbestadneset Åkrafjorden possible to do from mid-June until mid-September. It is a long and Leirvik demanding hike. Consider carefully whether you are in good enough shape Åkra HIKES Bremnes E39 and have the right equipment before setting out. Prepare well and be a LANGFOSS responsible and safe hiker. If you are inexperienced with challenging IN FJORD Skånevik mountain hikes, you should consider to join a guided tour to Trolltunga. Moster Hellandsbygd - A THRILLING WARNING – do not try to hike to Trolltunga in wintertime by your own. NORWAY Etne Sauda 520 WATERFALL Svandal E134 3 HOURS RETURN PHOTO: ESPEN MILLS Ølen Langevåg E39 3,5 KILOMETERS / ALTITUDE 640 METERS Vikebygd DIFFICULTY LEVEL RED (DEMANDING) 520 Sveio The sheer force of the 612-metre-high Langfossen waterfall in Vikedal Åkrafjorden is spellbinding. No wonder that the CNN has listed this 46 Suldalsosen E134 Nedre Vats Sand quintessential Norwegian waterfall as one of the ten most beautiful in the world. -

Prost Gerhard Henrik Reiner På Helleland, Fra 1790 Til 1823

Rolf Hetland Prost Gerhard Henrik Reiner på Helleland, fra 1790 til 1823. Prest i Helleland med Bjerkreim og Heskestad annekser Rolf Hetland, Ålgård har gjennom mange år samlet opplysninger om denne uvanlige presten som bodde i prestegården på Helleland i 33 år, og som etterlot seg en rekke historier og skriftlige beretninger fra folk som besøkte prestegården. Rolf Hetland kommer nå med en samlet framstilling om alt hva vi kjenner til om denne mannen – og det er ikke lite! Det er således første gang vi får en samlet oversikt om prestens virke – og da gjennom denne artikkelen. Presten var kjent for å kunne banne, han tuktet sine soknebarn med slag og kunne skjelle ut bygdefolk fra talerstolen i kirken, når han mente det var nødvendig. Og så kom han på kant med den kjente bondehøvdingen Tron Lauperak i Bjerkreim. Men blant «øvrigheten» var han vel ansett, og fikk utvidet sitt presteembete fra sogneprest i 1790 til prost i Dalane i 1800. Og i 1813 ble han utnevnt til ridder av Dannebrog. Rolf Hetland har også forsket i prestens bakgrunn, hvem var han og hvor kom han fra. Og hans tid som sjømannsprest i «Det Asiatiske Kompani» fra 1784 til 1788, med båtene «Mars» og «Dronning Juliane Marie» er også utførlig beskrevet. Presten var en svært velholden mann; Til sølvskatten i 1816 betalte han 10 ganger mer enn den rikeste bonden i kallet. Hvor pengene kom fra vet vi ikke, om det var slavehandelen han var med på, eller andre gode forretninger han gjorde som sjømann. Dette får stå ubesvart inntil noen går gjennom tollregnskapene da skutene ankret opp i Kjøbenhavn med Reiner ombord.