Norwegian Archaeological Review 'Figure It Out!' Psychological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presseliste Romjulstevne, Mandal & Holum

Presseliste Romjulstevne, Mandal & Holum - 27-28.12.2012: Mesterskap: Klasse 3-5: 1. Jan Kåre Moland, Drangedal 349, 2. Steinar Skoland, Lyngdal 345, 3. Arnfinn Bakkevoll, Søgne 345, 4. May Elin Frøyland, Lyngdal 344, 5. Daniel Tveiten Haig, Søgne 344, 6. Mette Elisabeth Finnestad, Søgne 344 V55: 1. Stein Østbøll, Birkenes 347, 2. Jon Olav Jåtun, Søgne 336, 3. Arild Rasmussen, Holum 335 Rekrutt: 1. Hanne Vidringstad, Lyngdal 341, 2. Andreas Finnestad Lund, Søgne 338, 3. Karen Øksendal, Holum 335 Eldre rekrutt: 1. Nina Vatne Alfsen, Vegårshei 349, 2. Karen-Oline Jacobsen, Holum 347, 3. Alvilde Røiseland, Holum 345, 4. Jardar Å Aarekol,, Klepp 345 Junior: 1. Ruth Jane Rossevatn, Øvre Eiken 344, 2. Henry Thorleif Jenssen, Mandal 339, 3. Rune Rossevatn, Øvre Eiken 335 V65: 1. Harald Jensen, Lyngdal 347, 2. Harald Englund, Søgne 347, 3. Oddbjørn Larsen, Torridal 345, 4. John Løland, Birkenes 345 V73: 1. Åsmund Idland, Gjesdal 349, 2. Tormod Aamdal, Søgne 340, 3. Odd Pettersen, Gjesdal 338 Hovedskyting: Klasse ASP: 1. Inger Marie Bringsdal, Holum 225, 1. Caroline Finnestad Lund, Søgne 245, 1. Nils Henrik Gyland, Greipstad 199, 1. William Høyland, Greipstad 179, 1. Magnus Johannessen, Søgne 212, 1. Marianne Rossevatn, Øvre Eiken 239, 1. Kristian Storenes, Imenes 240, 1. Fredrik Stubstad, Mandal 237, 1. Johan Valand, Grindølen 210 Klasse R: 1. Hanne Vidringstad, Lyngdal 243, 2. Andreas Finnestad Lund, Søgne 240, 3. Karen Øksendal, Holum 239, 4. Emma Gyland, Greipstad 235, 5. Tommy Lie Hortmann, Holum 233, 6. Kristoffer Aksnes, Søgne 230, 7. Jonas Øksendal, Holum 228,8. Marte Natalie Jacobsen, Holum 224 Klasse ER: 1. -

Joint Respiratory Emergency Room for Sandnes, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time and Hå

JOINT RESPIRATORY EMERGENCY ROOM FOR SANDNES, GJESDAL, KLEPP, TIME AND HÅ. Respiratory emergency room for Sandnes, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time and Hå: Weekdays at 08-15: For all five municipalities, the Sandnes emergency room receives telephone calls and patients with respiratory symptoms who need medical attention. Address: Brannstasjonsveien 2, 4312 Sandnes Weekdays at 15-23, weekends and holidays 08-23: For all five municipalities, the respiratory emergency room located at the premises of Klepp and Time emergency room receive telephone and patients with respiratory symptoms who need medical attention. Address: Olav Hålands veg 2, 4352 Kleppe Please do not show up without calling 116 117 first! Corona testing: You no longer need a doctor's referral to order a covid-19 test. However, it is important that you check the current criteria for testing before booking an appointment. You can order a corona test online at c19.no. Log in with electronic ID, provide contact information and state whether you are booking for yourself or for someone else. Once you have submitted the form, you will receive information about when and where to meet. You may experience getting an appointment as early as 45 minutes after booking. The waiting time depends on the current test capacity. Alternatively, you can call the emergency room to book an appointment. Daytime 08-15: Call 51 68 31 50 Afternoon, evening, and weekend: Call 51 42 99 99 Corona testing is performed at Kleppe. Please do not show up without an appointment. It is also important that you arrive precisely to the time you are allocated to avoid unnecessary queueing. -

Velkommen Til Holum Sfo

VELKOMMEN TIL HOLUM SFO SFO er et frivillig tilbud om tilsyn og omsorg før og etter skoletid. ” SFO skal være så strukturert at det skaper trygghet og forutsigbarhet, men så fritt at man føler man har fri” Søknadsfrist for opptak i SFO er 1. mars Søknad sendes elektronisk via Oppvekstportalen som du finner på Lindesnes kommune sin hjemmeside. Gå inn på oppvekstportalen: https://lindesnes.ist-asp.com Krever innlogging via ID-porten (Min ID, Bank-ID ol.) Barnet har plassen til den sies opp eller barnet går ut av 4. klasse. Besøksadresse: Møglandsveien 7, 4519 Holum Telefon: 47 68 53 73 (SFO kontor) 90938273 (SFO base) Mailadresse til SFO leder: [email protected] Skolefritidsordningen- SFO: Lindesnes kommune har et skolefritidstilbud før og etter skoletid for barn i 1-4 klasse ved alle barneskolene i kommunen. I SFO legges det vekt på at barna skal få mye tid til lek, kultur og fritidsaktiviteter med utgangspunkt i alder, funksjonsnivå og interesser. Ved Holum SFO er vi opptatt av trygghet. Barna og deres foresatte skal oppleve SFO som et trygt sted for barna både før og etter skolen. Vi legger vekt på at SFO skal være et lekende og humørfylt sted hvor vi har fokus på tilhørighet, valgfrihet, trivsel og vennskap. Personalet: Rektor har det overordnede ansvar for SFO. SFO har daglig leder med pedagogisk utdanning. De andre som jobber på SFO er barne- og ungdomsarbeidere/fagarbeidere. Åpningstider: SFO har åpner kl 06.45 og stenger kl 16.30 hver dag. Morgen SFO: Kl 06.45-08.50 alle skoledager Mandag: 14.35-16.30 Tirsdag: 13.40-16.30 Onsdag: 12.45-16.30 Torsdag: 14.35-16.30 Fredag: 12.45-16.30 I ferier har vi åpent fra kl 06.45-16.30 (for påmeldte barn) SFO sine åpningstider er tilpasset skolens timeplan for 1.- 4. -

New Records of Norwegian Sciomyzidae (Diptera)

New Records of Norwegian Sciomyzidae (Diptera) LITA GREVE AND BJ0RN 0KLAND Greve, L. & 0kland, B. 1989. New Records of Norwegian Sciomyzidae (Diptera). Fauna norv. Ser. B 36, 133-137. Records of 21 species of the family Sciomyzidae are give~. Pelidnopt~rafu.scipennis (Meigen, 1830), Antichaeta atriseta (Loew, 1849) and Ant/chaeta brevlpen.nlS (~etter stedt, 1846) are recorded for the first time from Norway. Se.veral species hitherto recorded from few localities in Norway are probably common m the country. Lita Greve, Zoological Museum, University of Bergen, Museplass 3, N-5007 Bergen, Norway. Bj0rn 0kland, Nordre Hammer gard, N-1473 Skarer, Norway. Rozko~ny (1984) published a comprehensive MATERIAL study on the Norwegian Sciomyzidae in the Pelidnoptera fuscipennis (Meigen, 1830) fourteenth Fauna Entomologica Scandin New records: TEI 1129 Kviteseid: Kviteseid avica volume. This survey included material EIS 17 Light trap, 23-27 June 1988 2~~, up to 1984 from all major Norwegian mu 11-20 July 1988 10' 1~ (ZMB). seums ofnatural history. Still, only 47 species P.fuscipennis is new to the fauna of Norway. are recorded from Norway, compared to 78 This species is the first of the genus recorded in neighbouring Sweden, 71 species in Fin from Norway. The trap was placed near a land and 67 in Denmark (Rozkohy 1984; small stream in a mixed forest. The species is Rozkosny & Greve, 1984). There are also distributed in southern Fennoscandia, but is comparatively few provincial records from not common (Rozko~ny, 1984). The biology Norway. ofthe Fennoscandian species ofPelidnoptera Thus, the present publication is based on are virtually unknown. -

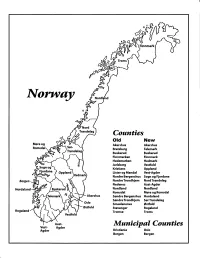

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Kyrkje Og Kulturi Sirdal

Aug 2016, årgang 5, nr 3 Kyrkje og kulturi Sirdal Besøk hos ASVO Inspirerende tur Kultursidene til Spania Side 4-6 Side 10-11 Side 18-28 Verdifull for Gud Omsorg og gjestfridom Gud vil ha fellesskap med oss. Han sø- To omgrep som er sentrale og viktige i for å koma seg bort frå krig og elende. ker og leiter, ser etter den bortkomne, - vår kristne tru og kulturarv. I denne utgå- etter den som er komen på avstand. va av bladet vårt er det tre artiklar som Innvandringa utanfrå har vore stor i Det er Han som vil ha med oss å gjere, på ulik vis illustrerar desse omgrepa. mange år tidlegare og. Det fekk vi illust- Johs. 3, 16-17: rert ved kyrkjelyden si vitjing i Barcelona, Vi har vitja ASVO, som gjev arbeid til mange kom utanfrå til Spania for fleire år ”For så elska Gud verda at han gav Son menneske med ulike yrkeshemmingar, sidan då tidene var gode, og det var lett å sin, den einborne, så kvar den som trur der tjue personar no har arbeid, ti har på han, ikkje skal gå fortapt, men ha få arbeid. No har mange menn reist vida- varig arbeid, nokre har arbeidspraksis og evig liv. Gud sende ikkje Son sin til verda re nordover for å skaffa seg arbeid, me- for at han skulle dømma verda, men for seks har språkpraksis. Arbeid er ein sers dan kvinnene og borna er att i Spania. Dei at verda skulle bli frelst ved han.” viktig del av livsinnhaldet, det gjev sjølv- har utfordringar med språk og integre- Johs.1,12: respekt, sosialt fellesskap og meining ring. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

3. Feltkarusell Holum Mesterskap Klasse 2-5 Og V55: 1. Steinar Skoland, Lyngdal 30/17, 2

3. Feltkarusell Holum Mesterskap Klasse 2-5 og V55: 1. Steinar Skoland, Lyngdal 30/17, 2. Geir Lie, Holum 30/14, 3. Georg Guldbrandsen, Heddeland og Breland 29/16, 4. Tor Arnfinn Homme, Topdal 29/15, 5. Oddvar Kvåle, Holum 29/11, 6. Kristoffer Eidså, Greipstad 29/10, 7. Børge Vatnedal, Holum 28/18, 8. Tor Harald Lund, Søgne 28/15, 9. Tom Nyhaven, Søgne 28/10, 10. Johan Sørli, Greipstad 28/07, 11. Ole Håkon Eidså, Greipstad 27/17, 12. Kjetil Norby, Randesund 27/13, 13. Arnfinn Bakkevoll, Søgne 27/13, 14. Henry Øvland, Greipstad 27/12, 15. Svein Jørund Gitmark, Lillesand 27/11, 16. Kennet Aas, Lyngdal 27/09, 17. Arild Rasmussen, Holum 26/13, 18. Arne Sløgedal, Heddeland og Breland 26/09, 19. Roar Torkildsen, Farsund 25/16, 20. Ingvar Aarhus, Greipstad 25/07, 21. Katrine Idland, Gjesdal 25/06, 22. Kjell Bang, Holum 25/05, 23. Robert Førland, Søgne 24/10, 24. Jane W. Johnsen, Heddeland og Breland 24/09, 25. Tor Ståle Knaben, Holum 24/09, 26. Johann Nygård, Randesund 24/09, 27. Geir Roland, Greipstad 24/08, 28. Sigurd Govertsen, Søgne 24/08, 29. Vidar Lauvsland, Øvrebø 24/07, 30. Catrine Fossdal, Greipstad 23/11, 31. Asbjørn Dale, Heddeland og Breland 23/11, 32. Tor Werner Carlson, Stavanger 23/07, 33. Jannike Eidså, Greipstad 23/05, 34. Martine S. Eikås, Søgne 22/11, 35. Tor Fasseland, Mandal 22/08, 36. Jon Olav Jåtun, Søgne 22/07, 37. Henning Strømland Strømland, Iveland 22/07, 38. Jarl Stølen, Farsund 21/12, 39. Egil Finnestad, Skjeberg 21/08, 40. -

World's Greatest Travel Destination

World’s greatest travel destination Foto: Terje Rakke/Nordic Life/Regionstavanger.com Finnøy, Rennesøy, Randaberg, Stavanger, Sandnes, Sola, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time, Hå, Bjerkreim, Eigersund, Lund, Sokndal, Sirdal Tourist boards and convention bureaus in Rogaland Destinasjon Haugesund og Haugalandet Reisemål Ryfylke Region Stavanger Finnøy, Rennesøy, Randaberg, Stavanger, Sandnes, Sola, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time, Hå, Bjerkreim, Eigersund, Lund, Sokndal, Sirdal Kva veit me om etterspurnad og turistane sine ynskje? Kva besøkande tapar Fjordveg- regionen? Finnøy, Rennesøy, Randaberg, Stavanger, Sandnes, Sola, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time, Hå, Bjerkreim, Eigersund, Lund, Sokndal, Sirdal 130 000 gjester i turistinformasjons kontorene i Stavanger og Sandneses Finnøy, Rennesøy, Randaberg, Stavanger, Sandnes, Sola, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time, Hå, Bjerkreim, Eigersund, Lund, Sokndal, Sirdal Finnøy, Rennesøy, Randaberg, Stavanger, Sandnes, Sola, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time, Hå, Bjerkreim, Eigersund, Lund, Sokndal, Sirdal Finnøy, Rennesøy, Randaberg, Stavanger, Sandnes, Sola, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time, Hå, Bjerkreim, Eigersund, Lund, Sokndal, Sirdal Spørsmål i turistinformasjonene: • Hvordan komme seg til Preikestolen? (50%) • Kan jeg kjøpe billetter til.....? • Har dere forslag på reiserute, ”scenic route” via... til...? • Hvilken vei anbefaler du vi skal kjøre til Bergen? Finnøy, Rennesøy, Randaberg, Stavanger, Sandnes, Sola, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time, Hå, Bjerkreim, Eigersund, Lund, Sokndal, Sirdal Spørsmål på email til [email protected] • De har dybdespørsmål om reiseruter -

Kommunevalgene 1919

NORGES OFFISIELLE STATISTIKK. VI. 189. KOMMUNEVALGENE 1919. (Élections en 1919 pour les conseils communaux et municipaux.) UTGITT AV DET STATISTISKE CENTRALBYRA. KRISTIANIA. I KOMMISJON HOS H. ASCHEHOUG & CO. 1920. Kommunevalgene 1907 med oplysninger om valgene i 1901 og delvis i 1904 se Norges Offisielle Statistikk, rekke V, 61; Kommunevalgene 1910, 1918 og 1916, se rekke V, 137 og rekke VI, 12 og 110. Kristiania — Arbeidernes Aktietrykkeri. Innhold. — Table des matières. Side (pages). Innledning. — Introduction 1* Tabell 1. Kommunevalgene i landdistriktene. Sammendrag fylkesvis. — Élections aux conseils communaux dans les districts ruraux, par préfecture. ........................ 2 — 2. Antall stemmeberettigede, avgivne stemmer og valgte repre- sentanter i de enkelte herreder. ~ Nombre des électeurs inscrits, des voies et des membres élus dans les communes rurales . 8 — 3. Kommunevalgene i byene. •—Élections aux conseils municipaux des villes 28 — 4. Antall stemmeberettigede og avgivne stemmer m. v. i de"mnrdre byer. — Nombre des électeurs inscrits et des votants, etc. dans les villes non-spécifiées au tableau précédent 33 — 5. De offisielle valglisters stemmetall ved forholds valg i land- distriktene. Sammendrag fylkesvis. — Élection proportionnelle dans les districts ruraux: nombre de voix des bulletins val- ables répartis sur partis, par préfecture 34 — 6. Representantplassenes fordeling på de enkeite partigruppers lister ved forholdsvalg i landdistriktene. Sammendrag fylkes- vis. — Élection proportionnelle dans les districts ruraux: représentants élus répartis sur partis, par préfecture 36 — 7. De offisielle valglisters stemmetall ved forholdsvalg i byene. — Élection proportionnelle dans les villes: nombre de voix des bulletins valables répartis sur partis 38 8. Representantplassenes fordeling på de enkelte partigruppers lister ved forholdsvalg i byene. — Élection proportionnelle dans les villes: représentants élus répartis sur partis 40 Innledning. -

Vessel Import to Norway in the First Millennium AD Composition And

VESSEL IMPORT TO NORWAY IN THE FIRST MILLENNIUM A.D Composition and context. by Ingegerd Roland Ph.D. thesis. Institute of Archaeology, University College London, June 1996. ProQuest Number: 10017303 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10017303 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract : More than 1100 complete or fragmentary imported vessels in bronze, glass, wood, horn, clay and silver from the first millennium A.D. have been found in Norway, approximately 80% of them in graves. The extensive research already carried out has produced a vast body of literature, which generally keeps within strict chronological boundaries, concentrating on vessels from either the Roman Period, the Migration Period, or the Viking Age. Two main approaches to the material have traditionally been applied: 1) typo logical studies, on the basis of which trade connections and systems have been discussed from different theoretical perspectives, and 2) imports as status markers, from which hierarchical social systems of a general kind have been inferred. Only very rarely have their function as vessels attracted any serious consideration, and even more rarely their actual local context. -

Norsk Bokfortegnelse / Norwegian National Bibliography

NORSK BOKFORTEGNELSE / NORWEGIAN NATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY NYHETSLISTE / LIST OF NEW BOOKS Utarbeidet ved Nasjonalbiblioteket Published by The National Library of Norway 2015 : 09 : 2 Alfabetisk liste / Alphabetical bibliography Registreringsdato / Date of registration: 2015.09.15-2015.09.30 [10. trinn] Maximum : matematikk for ungdomssteget. - Nynorsk[utg.]. - Oslo : Gyldendal undervisning, 2012- . - b. : ill. For Lærerens bok, se bokmålutg. Dewey: 1814 1814 : spillet om Danmark og Norge / [redaktion: Thomas Lyngby og Jan Romsaas ; tekst: Marit Berg ... [et al.]]. - Oslo : Norsk folkemuseum, 2014. - 135 s. : ill. ; 26 cm. Utgitt i samarbeid med Det Nationalhistoriske museum på Frederiksborgs slott. ISBN 978-87-87237-89-5 (h.) Dewey: 948.1034 948.9034 1st year report; the Sunniva project 1st year report; the Sunniva project : sustainable food production through quality optimized raw-material production and processing technologies for premium quality vegetable products and generated by-products / Trond Løvdal ... [et al.]. - Tromsø : Nofima, 2015. - 16 s. : ill. - (Report / Nofima ; 38/2015) Prosjektnr.: 10829. ISBN 978-82-8296-329-9 (h.) Dewey: A måling Fremstad, Kjersti, 1969- Tema : matematikk for småskolen / Kjersti Fremstad, Carl Kristian Kjølseth ; [illustrasjoner: Anette Heiberg]. - Bokmål[utg.]. - Oslo : Gan Aschehoug, 2014- . - b. : ill. - A tall. 2014. - 56 s. ; 30 cm. Katalogisert etter omslaget. ISBN 978-82-492-1655-0 (h.) : Nkr 139.00 - A måling. 2015. - 56 s. ; 30 cm. Katalogisert etter omslaget. ISBN 978-82-492-1810-3 (h.) : Nkr 139.00 Dewey: 1 A måling Fremstad, Kjersti, 1969- Tema : matematikk for småskulen / Kjersti Fremstad, Carl Kristian Kjølseth ; [illustrasjonar: Anette Heiberg ; omsett til nynorsk av Ole Jan Borgund]. - Nynorsk[utg.]. - Oslo : Gan Aschehoug, 2014- .