Time for a Fresh Start: the Report of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Real Love Story Camila Batmanghelidjh, Founder of Kids Company, Talks About Neuroplasticity

MUSE.09/10/12 A Real Love Story Camila Batmanghelidjh, founder of Kids Company, talks about neuroplasticity The Pride of the North How Gay Pride in York is changing perceptions Freshers’ Week 1964 What the crazy kids of York were up to in the Sixties M2 www.ey.com/uk/careers 09/10/12 Muse. M10 M12 M22 Features. Arts. Film. M4. Flamboyant psychotherapist Camila Bat- M18. Mary O’Connor speaks to poet and rap- M22. James Tyas interviews Sally El Hosaini, manghelidjh speaks to Sophie Rose Walker per Kate Tempest about love and we look back Director of My Brother the Devil, premiering at about the work of her charity Kids Company. at the legacy of Gustav Klimt. the BFI’s London Film Festival this October. M6. What is the frankly rather cool history of Freshers at York? Bella Foxwell investigates Fashion. Food & Drink. what’s changed and what hasn’t. M16. Ben Burns interviews fashion illustra- M23. Ward off Freshers Flu with Hana Teraie- M8. Gay Pride is out and thriving in York. tor Richard Kilroy, Miranda Larbi goes crazy for Wood’s delicous Ratatouille and Irish Coffee. Stefan Roberts and Tom Witherow looks at jacquard, and the ‘Whip-ma-Whop-ma’ shoot on Plus our review of Jamie Oliver’s new restaurant. the Northern scene’s dynamic. M12. M10. Young girls in Sri Lanka are prime Music. Image Credits. targets for terrorism training. Laura Hughes investigates why. M20. Death-blues duo Wet Nuns talk to Ally Cover: Kate Treadwell, Kids Company Swadling about facial hair, and there are stories Photoshoot: All photos credit to the marvellous from Pale Seas. -

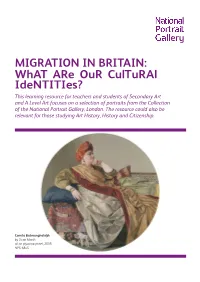

Migration in Britain

MIGRATION IN BRITAIN: WhAT ARe OuR CulTuRAl IdeNTITIes? This learning resource for teachers and students of Secondary Art and A Level Art focuses on a selection of portraits from the Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. The resource could also be relevant for those studying Art History, History and Citizenship. Camila Batmanghelidjh by Dean Marsh oil on plywood panel, 2008 NPG 6845 2/32 MIGRATION IN BRITAIN ABOuT ThIs ResOuRCe This resource tackles the question of what British cultural identities can mean and how people who constitute that sector of our society have and do contribute to it in a variety of different ways. This resource relates to another resource in on our website entitled Image and Identity. See: www. npg.org.uk/learning Each portrait is viewed and examined in a number of different ways with discussion questions and factual information relating directly to the works. The material in this resource can be used in the classroom or in conjunction with a visit to the Gallery. Students will learn about British culture through the ideas, methods and approaches used by portrait artists and their sitters over the last four hundred years. The contextual information provides background material that can be fed into the students' work as required. The guided discussion gives questions for the teacher to ask a group or class, it may be necessary to pose further questions around what culture can mean today to help explore and develop ideas more fully. Students should have the opportunity to pose their own questions, too. Each section contains the following: an introduction to each portrait, definitions, key words, questions and two art projects. -

A University of Sussex Phd Thesis Available Online Via Sussex

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Context is All: a qualitative case study of youth mentoring in the inner-city. Tasleem Rana Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex. September 2017 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: 3 Abstract This project is an extended case study design investigating the mentoring programme of Kids Company, an innovative and controversial organisation that closed during fieldwork. The study considers the programme both as a case of the larger category of ‘youth mentoring’ as well as a case in itself – of a unique and situated intervention. Methods employed included participant observation and interviews with professional staff, as well as the analysis of a sample of mentoring records documenting the one-year relationship of six mentoring pairs from the perspective of the mentor. Plans to interview mentoring pairs were curtailed by the unexpected demise of the organisation, but the data set includes interviews with five new mentors and mentees. -

![[2021] EWHC 175 (Ch)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5051/2021-ewhc-175-ch-2605051.webp)

[2021] EWHC 175 (Ch)

Neutral Citation Number: [2021] EWHC 175 (Ch) Case No: CR-2017-006113 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES INSOLVENCY AND COMPANIES LIST (ChD) Rolls Building, Royal Courts of Justice Fetter Lane, London, EC4A 1NL Date: 12/02/2021 IN THE MATTER OF KEEPING KIDS COMPANY AND IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANY DIRECTORS DISQUALIFICATION ACT 1986 Before: MRS JUSTICE FALK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: THE OFFICIAL RECEIVER Claimant -and- (1) SUNETRA ATKINSON (2) CAMILA BATMANGHELIDJH (3) ERICA JANE BOLTON (4) RICHARD GORDON HANDOVER (5) VINCENT O’BRIEN (6) FRANCESCA MARY ROBINSON (7) JANE TYLER (8) ANDREW WEBSTER (9) ALAN YENTOB Defendants - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Lesley Anderson QC and Gareth Tilley (instructed by Womble Bond Dickinson (UK) LLP) for the Claimant Rupert Butler (of Leverets) and Natasha Jackson (instructed by Leverets) for the Second Defendant Daniel Margolin QC and Daniel McCarthy (of Joseph Hage Aaronson LLP) for the Third Defendant George Bompas QC and Catherine Doran (instructed by Bates Wells) for the Fourth and Sixth to Ninth Defendants Andrew Westwood (instructed by Maurice Turnor Gardner LLP) for the Fifth Defendant MRS JUSTICE FALK Re Keeping Kids Company Approved Judgment Hearing dates: 19-22 and 26-29 October, 3-6, 9-12, 16-20, 23-26 and 30 November, 1-4, 7-9, 11 and 14-17 December 2020 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. …………….. Mrs Justice Falk 12 February 2021 14:27 Page 2 MRS JUSTICE FALK Re Keeping Kids Company Approved Judgment CONTENTS Paragraph INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. -

Child Health 6 with the Clean Air Acts of the 1950S, but Don’T ‘Get’ Public Health Or Appear to Be This Could Not Be Further from the Truth

THE FINAL WORD In this issue ‘ ’ > Camila Batmanghelidjh on the war against futility Josie Gibson won TV reality show Big Brother in > Why nekNominate is a sign of the times 2010. Following a series of comments and > Should we pay mums to breastfeed? photographs in the media about her weight, she The magazine of the UK Faculty of Public Health began to exercise more and eat sugar less www.fph.org.uk March 2014 FOR readers who don’t know who I am, sugar trap. A scary thought is that storage of fat. I went on a TV show about three years ago currently in the UK obesity rates have Sugar was my addiction and the thing and have been one of the lucky ones, as almost quadrupled in the past 25 years, that set me free was educating myself the show has given me a successful career and this rise has been accompanied by on diet and exercise. I found that after in doing what I love: helping people to lose a rise in sugar intake. Recent reports about 21 days of eating natural foods weight and get fit. I have struggled with and kicking the habit of sugar my mood my weight from the age of six, and it took swings and depression disappeared, and me 20 years to find the answer. This was one of the I had more energy than I had felt for a My key problem was the sheer amount long time. I really feel sorry for people of sugar I was consuming without even hardest achievements ‘ these days: it’s nearly impossible to have knowing it. -

State of Children's Rights in England

State of Children’s Rights in England | General measures of implementation iii STATE OF CHILDREN’S RIGHTS IN ENGLAND Review of Government action on United Nations’ recommendations for strengthening children’s rights in the UK iv State of Children’s Rights in England | General measures of implementation The Children’s Rights Alliance for England (CRAE) protects the human rights of children by lobbying government and others who hold power, by bringing or supporting test cases and by using regional and international human rights mechanisms. We provide free legal information, raise awareness of children’s human rights, and undertake research about children’s access to their rights. We mobilise others, including children and young people, to take action to promote and protect children’s human rights. CRAE has produced an annual State of Children’s Rights in England report since 2003. This report is the eleventh in the series. It summarises children’s rights developments from December 2012 to November 2013. We are very grateful to the organisations who provide Kalkan Gunes (Barnardo’s) funding for our vital monitoring and advocacy work: Kamena Dorling (Coram Children’s Legal Centre) Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, The Bromley Trust, Kate Mulley (Action for Children) The Children’s Society and UNICEF UK. Keith Clements (National Children’s Bureau) CRAE particularly thanks The National Society for the Lisa McCrindle (NSPCC) Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) for its generous Lisa Payne (UNICEF UK) donation towards this publication. Liz Davies (London Metropolitan University) Many individuals and organisations contributed to Louise King (Save the Children) this report by providing evidence, drafting sections and Lucy Emmerson (Sex Education Forum) commenting on drafts. -

Kids Company a Diagnosis of the Organisation and Its Interventions Final Report

KIDS COMPANY A DIAGNOSIS OF THE ORGANISATION AND ITS INTERVENTIONS FINAL REPORT Sandra Jovchelovitch Natalia Concha September 2013 KIDS COMPANY A DIAGNOSIS OF THE ORGANISATION AND ITS INTERVENTIONS FINAL REPORT Sandra Jovchelovitch Natalia Concha September 2013 RESEARCH TEAM Principal Investigator Sandra Jovchelovitch Research Manager Natalia Concha Researchers Rochelle Burgess Parisa Dashtipour Jacqueline Priego-Hernández Yvonne M. Whelan 2 CONTENTS Preface 5 Executive Summary 6 1. The Research: Studying Kids Company 10 1.1. Overview 10 1.2. Research Design and Methodology 11 1.3. The Structure of the Report 13 2. The Work of Kids Company: Integration of Evidence 15 2.1. Overview 15 2.2. The Clients: Social and Psychological Backgrounds 15 2.3. The Approach of Kids Company 18 2.4. The Delivery of Services 19 2.5. The Impact of Kids Company 21 2.6. Developmental Adversity: Biological and Psychosocial Consequences 22 2.7. Research Collaborations 24 2.8. Summary 24 3. Working at Kids Company: Results from the Survey 26 3.1. Overview 26 3.2. Findings 26 3.3. Summary 29 4. The Model of Work of Kids Company 31 4.1. The Model 31 4.2. The Principles of the Model 32 4.3. The Model in Practice: Delivery and Interfaces 37 4.4. Meeting the Needs of the Child 39 4.5. Summary 41 5. Chains of Scaffolding for Efficacy of Delivery 44 5.1. Staff Enabling Practices and Delivery 44 5.2. Scaffolding Staff 45 5.3. Scaffolding Relationships 47 5.4. Chains of Scaffolding: From Staff to Clients and Back 48 5.5. -

Vulnerable Children: Creating a Service Fit for Purpose

editorials Vulnerable children: creating a service fit for purpose barriers to access You would probably be surprised to know that over one-third of the children and young “... over one-third of the children and young people people who turn to Kids Company’s street level centres for help are not registered who turn to Kids Company’s street level centres with a GP. The barrier to access is sadly for help are not registered with a GP. The barrier simple, but also profoundly poignant. It’s the to access is sadly simple ... It’s the absence of a absence of a functioning carer. When your parent is out of control, your life falls apart. functioning carer.” As a nation, we have structured our health and social care services in such a way that there is a need for an administratively competent carer to navigate this path, who The very agencies that are supposed to The bottom line is that vast numbers of can connect the child to service providers step in to protect these children mimic their children, through a toxic combination of who sit in offices adhering to appointments. traumatised states. Workers swing between childhood maltreatment and poverty, are If your parent is the very person who is despair and disassociation, as they feel having their brains damaged. Their health abusing you, it is not likely you will be overwhelmed by the scale of the problems is set on a trajectory of disease, due to the taken to appointments at child mental they are facing. To protect themselves, they interference of relentless distress on their health centres. -

Relationships

Relationships - Year 9 Theme Assembly THEME: Relationships ASSEMBLY TITLE: Angel of Peckham - Camila Batmanghelidjh INTENDED OUTCOMES: For students to consider the work of Camila Batmanghelidjh, founder of Kids company For students to consider the importance of a sense of family and the importance of relationships in our lives. RESOURCES: Secondary assemblies for SEAL - 40 ready to deliver assemblies on inspirational people Brian Radcliffe - Optimus Education 2008 Pages 3-6 ASSEMBLY PRESENTATION: The assembly describes the work of Camila Batmanghelidgh in supporting children who are suffering with mental health or emotional difficulties due to their experiences of neglect or abuse. For many of these children their parents are unable to fulfil a parental role. The assembly invites students to think about the effects of this on a child or young person and develops empathy to consider the emotional, social and physical issues that may arise. It goes on to reflect on what children, young people and what we all need in our lives in terms of relationships and the importance of significant people. REFLECTION: How can we build trust and support for those around us and closest to us? How are we supported and cared for? How could we help others? Seal Key aspect Empathy SecoNdary aSSeMBlIeS for SEAL The angel of Peckham Camila Batmanghelidjh Key Stage 4 and 5 Taken by: Date: SEAL Key Aspect: empathy Given to: Summary: Comments: In this assembly students are encouraged to consider the work of camila Batmanghelidjh, the founder of the charity Kids company. Resources: l reader. Engagement Reflection Reader Leader Camila Batmanghelidjh is a very clever lady. -

Relationships

Relationships - Year 8 Theme Assembly THEME: Relationships ASSEMBLY TITLE: Angel of Peckham - Camila Batmanghelidjh INTENDED OUTCOMES: For students to consider the work of Camila Batmanghelidjh, founder of Kids company For students to consider the importance of a sense of family and the importance of relationships in our lives. RESOURCES: Secondary assemblies for SEAL - 40 ready to deliver assemblies on inspirational people Brian Radcliffe - Optimus Education 2008 Pages 3-6 ASSEMBLY PRESENTATION: The assembly describes the work of Camila Batmanghelidgh in supporting children who are suffering with mental health or emotional difficulties due to their experiences of neglect or abuse. For many of these children their parents are unable to fulfil a parental role. The assembly invites students to think about the effects of this on a child or young person and develops empathy to consider the emotional, social and physical issues that may arise. It goes on to reflect on what children, young people and what we all need in our lives in terms of relationships and the importance of significant people. REFLECTION: How can we build trust and support for those around us and closest to us? How are we supported and cared for? How could we help others? Seal Key aspect Empathy SecoNdary aSSeMBlIeS for SEAL The angel of Peckham Camila Batmanghelidjh Key Stage 4 and 5 Taken by: Date: SEAL Key Aspect: empathy Given to: Summary: Comments: In this assembly students are encouraged to consider the work of camila Batmanghelidjh, the founder of the charity Kids company. Resources: l reader. Engagement Reflection Reader Leader Camila Batmanghelidjh is a very clever lady. -

Kids Company

An ‘unusual jewel’ Reflections on the demise of Kids Company Rob Macmillan Third Sector Research Centre University of Birmingham www.tsrc.ac.uk [email protected] 8th December 2015 Who or what is most responsible for the demise of Kids Company, out of the following… (pick only one!) 1 (Chair) 2 (media) 3 (Chief Executive) 4 (PM, Big Society) 5 (regulators) 6 (Oliver Letwin) The basic argument • Recounting the demise of Kids Company – timeline • Theory: failure, fields • Field processes: animation, translation, escalation, distinction • Settling accounts: a hegemonic account, based on governance failure and financial vulnerability An unusual jewel? it was a very unusual jewel in our funding crown. It seemed to draw a lot of political interest. It seemed to draw a lot of annual public money. It had unorthodox methods. It seemed to operate outside the statutory framework in local authorities...Ministers are entitled to fund innovation. It seemed to have low reserves and therefore coming to us was always slightly last-minute (Richard Heaton, former Permanent Secretary, Cabinet Office, 2.11.15) ‘Big Society Poster Girl’ (Tim Loughton, MP, 19.11.15) Kids Company (2014) Campaign launched 24.6.14 after Centre for Social Justice report “Enough is enough” highlights state failure in child protection …This isn’t about Kids Company, and we don’t claim to have all the answers. We are aiming to mobilise the public to demand the formation of a cross- party government task force to outline a 15-year recovery programme for our statutory children’s services…. The task force will be independent of Kids Company. -

SAR HP 522 Syllabus SP11

Boston University British Programmes Health and Wellness through the Lifespan SAR HP 522 (Elective B) Spring 2011 Instructor Information A. Names Professors Stephen Clift and Claudia Hammond B. Day and Time Mondays, 1.15-5.15pm C. Location Wetherby room, 43 Harrington Gardens, SW7 4JU D. Telephone 01277 711698 (messages can be left) E. Email [email protected] and [email protected] F. Webpage http://www.bu-london.co.uk/academic/hp522 G. Office hours By appointment Course Objectives This course aims to explore concepts of health and wellbeing and to examine important social, cultural and psychological factors impacting on health and wellbeing across the lifespan. Particular attention will be given to issues and research relating to the UK but discussion will be set within a wider global and European context. Efforts will also be made to link reading and discussion within the course, to students’ on-going experiences in their internship placements. Assessment There are two aspects to the assessment of this course: 1. A paper of 2,000 words (50%) based on the issues addressed during the course Deadline: 5pm, Monday 18th April to the Student Affairs Office 2. A two-hour exam (50%) The title of the paper should be discussed and agreed with the course tutor. The Examination Section 1 of the examination will involve discussion of an individual case study drawing on the conceptual frameworks outlined in key texts on the lifespan perspective on health and wellness. Section 2 will involve answering two questions, one related to the issues covered on the course and one related to the visits undertaken.