Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meningitis: Immunizations on Pennsylvania College

JOINT STATE GOVERNMENT COMMISSION General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania MENINGITIS: IMMUNIZATIONS ON PENNSYLVANIA COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES APRIL 2020 Serving the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Since 1937 - 1 - REPORT Meningitis: Immunizations on Pennsylvania College and University Campuses Project Manager: Susan Elder, Fiscal Analyst Allison Kobzowicz, Public Policy Analyst Stephen Kramer, Staff Attorney Project Staff: Wendy Baker, Executive Assistant Kahla Lukens, Administrative Assistant (Dec. 2019) Maureen Hartwell, Public Policy Analyst Intern (Aug. 2019) The report is also available at http://jsg.legis.state.pa.us - 0 - JOINT STATE GOVERNMENT COMMISSION Telephone: 717-787-4397 Room 108 Finance Building Fax: 717-783-9380 613 North Street E-mail: [email protected] Harrisburg, PA 17120-0108 Website: http://jsg.legis.state.pa.us The Joint State Government Commission was created in 1937 as the primary and central non- partisan, bicameral research and policy development agency for the General Assembly of Pennsylvania.1 A fourteen-member Executive Committee comprised of the leadership of both the House of Representatives and the Senate oversees the Commission. The seven Executive Committee members from the House of Representatives are the Speaker, the Majority and Minority Leaders, the Majority and Minority Whips, and the Majority and Minority Caucus Chairs. The seven Executive Committee members from the Senate are the President Pro Tempore, the Majority and Minority Leaders, the Majority and Minority Whips, and the Majority and Minority Caucus Chairs. By statute, the Executive Committee selects a chairman of the Commission from among the members of the General Assembly. Historically, the Executive Committee has also selected a Vice-Chair or Treasurer, or both, for the Commission. -

A Brief History of Vaccines & Vaccination in India

[Downloaded free from http://www.ijmr.org.in on Wednesday, August 26, 2020, IP: 14.139.60.52] Review Article Indian J Med Res 139, April 2014, pp 491-511 A brief history of vaccines & vaccination in India Chandrakant Lahariya Formerly Department of Community Medicine, G.R. Medical College, Gwalior, India Received December 31, 2012 The challenges faced in delivering lifesaving vaccines to the targeted beneficiaries need to be addressed from the existing knowledge and learning from the past. This review documents the history of vaccines and vaccination in India with an objective to derive lessons for policy direction to expand the benefits of vaccination in the country. A brief historical perspective on smallpox disease and preventive efforts since antiquity is followed by an overview of 19th century efforts to replace variolation by vaccination, setting up of a few vaccine institutes, cholera vaccine trial and the discovery of plague vaccine. The early twentieth century witnessed the challenges in expansion of smallpox vaccination, typhoid vaccine trial in Indian army personnel, and setting up of vaccine institutes in almost each of the then Indian States. In the post-independence period, the BCG vaccine laboratory and other national institutes were established; a number of private vaccine manufacturers came up, besides the continuation of smallpox eradication effort till the country became smallpox free in 1977. The Expanded Programme of Immunization (EPI) (1978) and then Universal Immunization Programme (UIP) (1985) were launched in India. The intervening events since UIP till India being declared non-endemic for poliomyelitis in 2012 have been described. Though the preventive efforts from diseases were practiced in India, the reluctance, opposition and a slow acceptance of vaccination have been the characteristic of vaccination history in the country. -

Anti-Vaccinationism and Public Health in Nineteenth-Century England

Medical History, 1988, 32: 231-252. THE POLITICS OF PREVENTION: ANTI-VACCINATIONISM AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND by DOROTHY PORTER AND ROY PORTER* THE FRAMING OF THE LAW ON COMPULSORY VACCINATION AND THE ORGANIZATION OF OPPOSITION The coming of compulsory health legislation in mid-nineteenth-century England was a political innovation that extended the powers of the state effectively for the first time over areas of traditional civil liberties in the name of public health. This development appears most strikingly in two fields of legislation. One instituted compulsory vaccination against smallpox, the other introduced a system of compulsory screening, isolation, and treatment for prostitutes suffering from venereal disease, initially in four garrison towns.' The Vaccination Acts and the Contagious Diseases Acts suspended what we might call the natural liberty of the individual to contract and spread infectious disease, in order to protect the health ofthe community as a whole.2 Both sets oflegislation were viewed as infractions ofliberty by substantial bodies of Victorian opinion, which campaigned to repeal them. These opponents expressed fundamental hostility to the principle ofcompulsion and a terror of medical tyranny. The repeal organizations-above all, the Anti- Compulsory Vaccination League and the National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts-were motivated by different sets of social and scientific values.3 Nevertheless, their activities jointly highlight some of the political conflicts produced by the creation of a public health service in the nineteenth century, issues with resonances for the state provision of health care up to the present day. Compulsory vaccination was established by the Vaccination Act of 1853, following a report compiled by the Epidemiological Society on the state ofvaccination since the *Dorothy Porter, PhD, and Roy Porter, PhD, Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 183 Euston Road, London NWI 2BP. -

The English Revolution in Social Medicine, 1889-1911

THE ENGLISH REVOLUTION IN SOCIAL MEDICINE, 1889-1911 UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PhD THESIS DOROTHY E. WATKINS 1984 To J.D.M.W. and E.C.W. 2 ABSTRACT The dissertation examines the development of preventive medicine between 1889-1911. It discusses the rise of expertise in prevention during this period and the consolidation of experts into a professional body. In this context the career histories of medical officers of health in London have been analysed to provide a basis for insight into the social structure of the profession. The prosopog- raphy of metropolitan officers demonstrated a broad spectrum of recruitment from the medical profession and the way in which patterns of recruitment changed over time. The level of specialisation in preventive medicine has been examined through a history of the development of the Diploma in Public Health. The courses and qualifying examinations undertaken by medical officers of health revealed the way in which training was linked to professionalisation through occupational monopoly. The association representing the interests of medical officers of health, their own Society, was Investigated through its recorded minutes of Council and Committees from the year it was first amalgamated into a national body, 1889, up to the date of the National Insur- ance Act in 1911. Here the aims and goals of the profession were set against their achievements and failures with regard to the new patterns of health care provision emerging during this period. This context of achievement and failure has been contrasted with an examination of the 'preventive ideal', as it was generated from within the community of preventive medical associations, of which the Society of Medical Officers of Health was one member. -

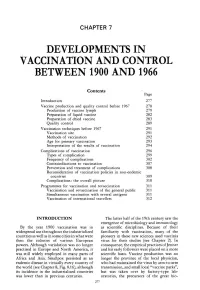

Chapter 7. Developments in Vaccination and Control Between

CHAPTER 7 DEVELOPMENTS IN VACCINATION AND CONTROL BETWEEN 1900 AND 1966 Contents Page Introduction 277 Vaccine production and quality control before 1967 278 Production of vaccine lymph 279 Preparation of liquid vaccine 282 Preparation of dried vaccine 283 Quality control 289 Vaccination techniques before 1967 291 Vaccination site 291 Methods of vaccination 292 Age for primary vaccination 293 Interpretation of the results of vaccination 294 Complications of vaccination 296 Types of complication 299 Frequency of complications 302 Contraindications to vaccination 307 Prevention and treatment of complications 308 Reconsideration of vaccination policies in non-endemic countries 309 Complications : the overall picture 310 Programmes for vaccination and revaccination 311 Vaccination and revaccination of the general public 311 Simultaneous vaccination with several antigens 311 Vaccination of international travellers 312 INTRODUCTION The latter half of the 19th century saw the emergence of microbiology and immunology By the year 1900 vaccination was in as scientific disciplines . Because of their widespread use throughout the industrialized familiarity with vaccination, many of the countries as well as in some cities in what were pioneers in these new sciences used vaccinia then the colonies of various European virus for their studies (see Chapter 2) . In powers . Although variolation was no longer consequence, the empirical practices of Jenner practised in Europe and North America, it and his early followers were placed on a more was still widely employed in many parts of scientific basis . Vaccine production was no Africa and Asia . Smallpox persisted as an longer the province of the local physician, endemic disease in virtually every country of who had maintained the virus by arm-to-arm the world (see Chapter 8, Fig. -

Reassessing Vaccination in England, 1796-1853

International Social Science Review Volume 95 Issue 3 Article 2 “A Splendid Delusion:” Reassessing Vaccination in England, 1796-1853 Kaitlyn Akel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/issr Part of the Anthropology Commons, Communication Commons, Economics Commons, Geography Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Akel, Kaitlyn () "“A Splendid Delusion:” Reassessing Vaccination in England, 1796-1853," International Social Science Review: Vol. 95 : Iss. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/issr/vol95/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Social Science Review by an authorized editor of Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. “A Splendid Delusion:” Reassessing Vaccination in England, 1796-1853 Cover Page Footnote Kaitlyn Akel holds a B.A. in History and a B.S. in Biology from the University of Arkansas, and is currently a MPH candidate at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. This article is available in International Social Science Review: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/issr/vol95/ iss3/2 Akel: “A Splendid Delusion:” Reassessing Vaccination in England, 1796-1853 “A Splendid Delusion:” Reassessing Vaccination in England, 1796-1853 Public health interventions integrate into our present-day habits to the point of imperceptibility. Policies revolve around our speed limits, employee sanitation standards, food preparation policies, immunization mandates: all with the encompassing intent to increase our fitness in society. This was not the case in nineteenth century England. -

Bovine Tuberculosis and Tuberculin Testing in Britain, 1890–1939

Medical History http://journals.cambridge.org/MDH Additional services for Medical History: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here To Stamp Out “So Terrible a Malady”: Bovine Tuberculosis and Tuberculin Testing in Britain, 1890–1939 Keir Waddington Medical History / Volume 48 / Issue 01 / January 2004, pp 29 - 48 DOI: 10.1017/S0025727300007043, Published online: 26 July 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0025727300007043 How to cite this article: Keir Waddington (2004). To Stamp Out “So Terrible a Malady”: Bovine Tuberculosis and Tuberculin Testing in Britain, 1890–1939. Medical History, 48, pp 29-48 doi:10.1017/S0025727300007043 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/MDH, IP address: 131.251.254.13 on 25 Feb 2014 Medical History, 2004, 48: 29±48 To Stamp Out ``So Terrible a Malady'': Bovine Tuberculosis and Tuberculin Testing in Britain, 1890±1939 KEIR WADDINGTON* In the early-twentieth century, movesto prevent infection from tuberculosisbecamean integral part of local government public health schemes.1 While the scale of action was dependent on individual authorities and ratepayers, interest was not limited to the pulmon- ary form of the disease. Effort was also directed at tackling bovine tuberculosis, which by the 1890s had become ``the most important disease of cows'' and, with its zoonotic proper- ties accepted, ``a substantial risk to the ...consumer''.2 With meat and milk identified asthe main vectors, moves to detect infected livestock and limit the spread of the disease became part of a wider preventive strategy. Measures were introduced to control the sale of tuber- culousmeat and milk. -

Anti-Vaccinationism and Public Health in Nineteenth-Century England

Medical History, 1988, 32: 231-252. THE POLITICS OF PREVENTION: ANTI-VACCINATIONISM AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND by DOROTHY PORTER AND ROY PORTER* THE FRAMING OF THE LAW ON COMPULSORY VACCINATION AND THE ORGANIZATION OF OPPOSITION The coming of compulsory health legislation in mid-nineteenth-century England was a political innovation that extended the powers of the state effectively for the first time over areas of traditional civil liberties in the name of public health. This development appears most strikingly in two fields of legislation. One instituted compulsory vaccination against smallpox, the other introduced a system of compulsory screening, isolation, and treatment for prostitutes suffering from venereal disease, initially in four garrison towns.' The Vaccination Acts and the Contagious Diseases Acts suspended what we might call the natural liberty of the individual to contract and spread infectious disease, in order to protect the health ofthe community as a whole.2 Both sets oflegislation were viewed as infractions ofliberty by substantial bodies of Victorian opinion, which campaigned to repeal them. These opponents expressed fundamental hostility to the principle ofcompulsion and a terror of medical tyranny. The repeal organizations-above all, the Anti- Compulsory Vaccination League and the National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts-were motivated by different sets of social and scientific values.3 Nevertheless, their activities jointly highlight some of the political conflicts produced by the creation of a public health service in the nineteenth century, issues with resonances for the state provision of health care up to the present day. Compulsory vaccination was established by the Vaccination Act of 1853, following a report compiled by the Epidemiological Society on the state ofvaccination since the *Dorothy Porter, PhD, and Roy Porter, PhD, Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 183 Euston Road, London NWI 2BP. -

List X: Natural Science, Medicine, and Mathematics Part II

Antiquates – Fine and Rare Books List X: Natural Science, Medicine, and Mathematics Part II Antiquates Ltd, The Conifers, Valley Road, Corfe Castle, Dorset, BH20 5HU. United Kingdom Tel: 07921 151496 Email: [email protected] Web: www.antiquates.co.uk 51) LEMERY, M. Nicolas. Cours de chymie. Contenant la maniere de faire les Operations qui sont en usage dans la Medecine, par une Methode facile. Avec des raisonnemens sur chaque Operation, pour l'instruction de ceux qui veulent s'appliquer a cette Science. A Leyde. Chez Theodore Haak, 1716. Onzie'me edition. 8vo. [20], 937pp, [31]. With an engraved frontispiece and eight woodcut plates (one folding). Title in red and black. Contemporary speckled calf with contrasting red morocco lettering-piece, spine richly gilt. Rubbed with significant loss to lettering-piece, chipping to head of spine, surface scratches to upper board. Ink stamps to FEP of Ben Damph Forest Library and 'Ashley Combe' respectively. Browning to final three leaves of index. Nicholas Lemery (1645-1715), French chemist. A pupil of the Parisian alchemist Christophe Glaser, Lemery considered chemistry to be a more scientific subject not worthy of the speculation of alchemy. Proceeding from demonstrable fact, and expounding from physical observations and chemical experiments, Lemery's stature as both lecturer and author was unrivalled in late seventeenth century Europe. First published 1675, his Cours de chymie went through 13 French editions, numerous foreign translations, and proved to be the standard work of the European Enlightenment. £ 350 52) LIPSIUS, David. [GREEK TITLE] Davidis Lipsi Iscanti Doctoris Medici & C. P. Caes. Tractatus de hydropisis Ejjusque Specierum Trilic. -

Volume 1: Issue 2

VOLUME 1: ISSUE 2 || APRIL 2019 || Email: [email protected] Website:www.whiteblacklegal.co.in Page | 1 DISCLAIMER No part of this publication may be reproduced or copied in any form by any means without prior written permission of Editor-in-chief of WhiteBlackLegal – The Law Journal. The Editorial Team of WhiteBlackLegal holds the copyright to all articles contributed to this publication. The views expressed in this publication are purely personal opinions of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Editorial Team of WhiteBlackLegal or Legal Education Awareness Foundation. Though all efforts are made to ensure the accuracy and correctness of the information published, Jurisperitus shall not be responsible for any errors caused due to oversight or otherwise. Page | 2 EDITORIAL TEAM EDITOR IN CHIEF Name - Mr. Varun Agrawal Consultant || SUMEG FINANCIAL SERVICES PVT.LTD. Phone - +91-9990670288 Email - [email protected] EDITOR Name - Mr. Anand Agrawal Consultant|| SUMEG FINANCIAL SERVICES PVT.LTD. Phone - +91-9810767455 Email - [email protected] EDITOR (HONORARY) Name - Smt Surbhi Mittal Manager || PSU Phone - +91-9891639509 Email - [email protected] EDITOR(HONORARY) Name - Mr Praveen Mittal Consultant || United Health Group MNC Phone - +91-9891639509 Email - [email protected] EDITOR Name - Smt Sweety Jain Consultant||SUMEG FINANCIAL SERVICES PVT.LTD. Phone - +91-9990867660 Email - [email protected] EDITOR Name - Mr. Siddharth Dhawan Core Team Member || Legal Education Awareness Foundation Phone - +91 -9013078358 Page | 3 ABOUT US WHITEBLACKLEGAL is an open access, peer-reviewed and refereed journal provide dedicated to express views on topical legal issues, thereby generating a cross current of ideas on emerging matters. -

Anti-Vaccinationism and Public Health in Nineteenth-Century England

Medical History, 1988, 32: 231-252. THE POLITICS OF PREVENTION: ANTI-VACCINATIONISM AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND by DOROTHY PORTER AND ROY PORTER* THE FRAMING OF THE LAW ON COMPULSORY VACCINATION AND THE ORGANIZATION OF OPPOSITION The coming of compulsory health legislation in mid-nineteenth-century England was a political innovation that extended the powers of the state effectively for the first time over areas of traditional civil liberties in the name of public health. This development appears most strikingly in two fields of legislation. One instituted compulsory vaccination against smallpox, the other introduced a system of compulsory screening, isolation, and treatment for prostitutes suffering from venereal disease, initially in four garrison towns.' The Vaccination Acts and the Contagious Diseases Acts suspended what we might call the natural liberty of the individual to contract and spread infectious disease, in order to protect the health ofthe community as a whole.2 Both sets oflegislation were viewed as infractions ofliberty by substantial bodies of Victorian opinion, which campaigned to repeal them. These opponents expressed fundamental hostility to the principle ofcompulsion and a terror of medical tyranny. The repeal organizations-above all, the Anti- Compulsory Vaccination League and the National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts-were motivated by different sets of social and scientific values.3 Nevertheless, their activities jointly highlight some of the political conflicts produced by the creation of a public health service in the nineteenth century, issues with resonances for the state provision of health care up to the present day. Compulsory vaccination was established by the Vaccination Act of 1853, following a report compiled by the Epidemiological Society on the state ofvaccination since the *Dorothy Porter, PhD, and Roy Porter, PhD, Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 183 Euston Road, London NWI 2BP. -

Inoculation of Cowpox) and the Potential Role of Horsepox Virus in the Origin of the Smallpox Vaccine ⇑ José Esparza A, , Livia Schrick B, Clarissa R

Vaccine 35 (2017) 7222–7230 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Vaccine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vaccine Review Equination (inoculation of horsepox): An early alternative to vaccination (inoculation of cowpox) and the potential role of horsepox virus in the origin of the smallpox vaccine ⇑ José Esparza a, , Livia Schrick b, Clarissa R. Damaso c, Andreas Nitsche b a Institute of Human Virology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA b Centre for Biological Threats and Special Pathogens 1 – Highly Pathogenic Viruses & German Consultant Laboratory for Poxviruses & WHO Collaborating Centre for Emerging Infections and Biological Threats, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany c Laboratório de Biologia Molecular de Virus, Instituto de Biofísica Carlos Chagas Filho, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil article info abstract Article history: For almost 150 years after Edward Jenner had published the ‘‘Inquiry” in 1798, it was generally assumed Received 20 September 2017 that the cowpox virus was the vaccine against smallpox. It was not until 1939 when it was shown that Received in revised form 18 October 2017 vaccinia, the smallpox vaccine virus, was serologically related but different from the cowpox virus. In the Accepted 2 November 2017 absence of a known natural host, vaccinia has been considered to be a laboratory virus that may have Available online 11 November 2017 originated from mutational or recombinational events involving cowpox virus, variola viruses or some unknown ancestral Orthopoxvirus. A favorite candidate for a vaccinia ancestor has been the horsepox Keywords: virus. Edward Jenner himself suspected that cowpox derived from horsepox and he also believed that Cowpox ‘‘matter” obtained from either disease could be used as preventative of smallpox.