ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Strings Considered a Subjective List of Classical Works

All Strings Considered A Subjective List of Classical Works & Recordings All Recordings are available from the Lake Oswego Public Library These are my faves, your mileage may vary. Bill Baars, Director Composer / Title Performer(s) Comments Middle Ages and Renaissance Sequentia We carry a lot of plainsong and chant; HILDEGARD OF BINGEN recordings by the Anonymous 4 are also Antiphons highly recommended. Various, Renaissance vocal and King’s Consort, Folger Consort instrumental collections. or Baltimore Consort Baroque Era Biondi/Europa Galante or Vivaldi wrote several hundred concerti; try VIVALDI Loveday/Marriner. the concerti for multiple instruments, and The Four Seasons the Mandolin concerti. Also, Corelli's op. 6 and Tartini (my fave is his op.96). HANDEL Asch/Scholars Baroque For more Baroque vocal, Bach’s cantatas - Messiah Ensemble, Shaw/Atlanta start with 80 & 140, and his Bach B Minor Symphony Orch. or Mass with John Gardiner conducting. And for Jacobs/Freiberg Baroque fun, Bach's “Coffee” cantata. orch. HANDEL Lamon/Tafelmusik For an encore, Handel's “Music for the Royal Water Music Suites Fireworks.” J.S. BACH Akademie für Alte Musik Also, the Suites for Orchestra; the Violin and Brandenburg Concertos Berlin or Koopman, Pinnock, Harpsicord Concerti are delightful, too. or Tafelmusik J.S. BACH Walter Gerwig More lute - anything by Paul O'Dette, Ronn Works for Lute McFarlane & Jakob Lindberg. Also interesting, the Lute-Harpsichord. J.S. BACH Bylsma on period cellos, Cello Suites Fournier on a modern instrument; Casals' recording was the standard Classical Era DuPre/Barenboim/ECO & HAYDN Barbirolli/LSO Cello Concerti HAYDN Fischer, Davis or Kuijiken "London" Symphonies (93-101) HAYDN Mosaiques or Kodaly quartets Or start with opus 9, and take it from there. -

TOC 0245 CD Booklet.Indd

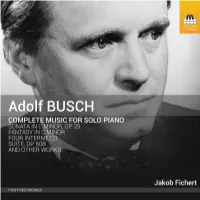

ADOLF BUSCH AND THE PIANO by Jakob Fichert It’s hardly a secret that Adolf Busch (1891–1952) was one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth century. But only specialists, it seems, are aware that he was also a very fne composer, even though these two artistic identities – performer and composer – were of equal importance to him. In recent years some of his chamber works, his organ music and parts of his symphonic œuvre have been recorded, allowing some appreciation of his stature as a creative fgure. But Busch’s music for solo piano has yet to be discovered – only the Andante espressivo, BoO1 37 22 , has been recorded before now, by Peter Serkin, Busch’s grandson, and that in a private recording, not available commercially. Tis album therefore presents the entirety of Busch’s piano output for the frst time. Busch’s writing for solo piano forms a kind of huge triptych, with the Sonata in C minor, Op. 25, as its central panel; another major work, a Fantasia in C major, BoO 20, was written early in his career; and a later Suite, Op. 60b, dates from the time of his full maturity. Busch also wrote more than a dozen smaller piano pieces, in which he seems to have experimented with various genres in pursuit of the development of his musical language, with four Intermezzi, a Scherzo and other character pieces among them. One can hear the infuence of Brahms, Mendelssohn, Busoni and – especially – Reger, but with familiarity Busch’s style can be heard to be distinctive and personal, displaying a unique and highly expressive world of sound. -

110988 Bk Menuhin 19/07/2004 11:42Am Page 4

110988 bk Menuhin 19/07/2004 11:42am Page 4 Ward Marston ADD In 1997 Ward Marston was nominated for the Best Historical Album Grammy Award for his production work on Great Violinists • Menuhin 8.110988 BMG’s Fritz Kreisler collection. According to the Chicago Tribune, Marston’s name is ‘synonymous with tender loving care to collectors of historical CDs’. Opera News calls his work ‘revelatory’, and Fanfare deems him ‘miraculous’. In 1996 Ward Marston received the Gramophone award for Historical Vocal Recording of the Year, honouring his production and engineering work on Romophone’s complete recordings of Lucrezia Bori. He also served as re-recording engineer for the Franklin Mint’s Arturo Toscanini issue and BMG’s Sergey Rachmaninov recordings, both winners of the Best Historical Album Grammy. Born blind in 1952, Ward Marston has amassed tens of thousands of opera classical records over the past four MOZART decades. Following a stint in radio while a student at Williams College, he became well-known as a reissue producer in 1979, when he restored the earliest known stereo recording made by the Bell Telephone Laboratories in 1932. Violin Sonatas In the past, Ward Marston has produced records for a number of major and specialist record companies. Now he is bringing his distinctive sonic vision to bear on works released on the Naxos Historical label. Ultimately his goal is to make the music he remasters sound as natural as possible and true to life by ‘lifting the voices’ off his old 78 rpm K. 376 and K. 526 recordings. His aim is to promote the importance of preserving old recordings and make available the works of great musicians who need to be heard. -

Program Notes | January 25/26

PROGRAM NOTES | JANUARY 25/26 George Walker in musical composition turned serious after LYRIC FOR STRINGS graduating from Curtis. He went to Europe and Born in Washington, D.C., June 27, 1922 studied with Nadia Boulanger. Upon returning Died in Montclair, New Jersey, to the States, he earned his Doctoral degree in August 23, 2018 composition from the Eastman School of Music. Last performed by the Wichita Symphony Teaching was the third component of Walker’s December 10/11, 1994 life in music. He enjoyed positions at Smith College, the University of Colorado, and most Most people in the audience this weekend may importantly at Rutgers University in New be encountering the music of George Walker Jersey, where he taught for twenty-three years for the first time. The Lyric for Strings, Walker’s until his retirement in 1992. most performed work is an appropriate introduction as it makes a long overdue Walker’s list of compositions includes over 100 appearance on a Wichita Symphony program. works covering a wide range of genres, from sonatas, quartets, art songs, choral works, Described by one writer as “an under-heard to symphonic works. He received numerous American Master,” George Walker’s was a awards including the Pulitzer Prize for Music in “trailblazer” in a career full of firsts for an 1996 for Lilacs, a work for voice and orchestra African-American musician: one of the first based on poetry by Walt Whitman. Many to graduate from the Curtis Institute of Music leading orchestras and organizations including (1945), first to give a Town Hall debut recital the Boston Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, on piano (1945), perform as a soloist with New York Philharmonic, the John F. -

A Listening Guide for the Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini

A Listening Guide for The Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini 1 The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide Anthony Tommasini A listening guide INTRODUCTION: The Greatness Complex Bach, Mass in B Minor I: Kyrie I begin the book with my recollection of being about thirteen and putting on a recording of Bach’s Mass in B Minor for the first time. I remember being immediately struck by the austere intensity of the opening choral singing of the word “Kyrie.” But I also remember feeling surprised by a melodic/harmonic shift in the opening moments that didn’t do what I thought it would. I guess I was already a musician wanting to know more, to know why the music was the way it was. Here’s the grave, stirring performance of the Kyrie from the 1952 recording I listened to, with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. Though, as I grew to realize, it’s a very old-school approach to Bach. Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Vienna Philharmonic (12:17) Today I much prefer more vibrant and transparent accounts, like this great performance from Philippe Herreweghe’s 1996 recording with the chorus and orchestra of the Collegium Vocale, which is almost three minutes shorter. Philippe Herreweghe, conductor; Collegium Vocale Gent (9:29) Grieg, “Shepherd Boy” Arthur Rubinstein, piano Album: “Rubinstein Plays Grieg” (3:26) As a child I loved “Rubinstein Plays Grieg,” an album featuring the great pianist Arthur Rubinstein playing piano works by Grieg, including several selections from the composer’s volumes of short, imaginative “Lyrical Pieces.” My favorite was “The Shepherd Boy,” a wistful piece with an intense middle section. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Adolf Busch: the Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Online

yiMmZ (Ebook pdf) Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Online [yiMmZ.ebook] Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Pdf Free Tully Potter DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3756817 in Books Toccata Press 2010-09-17Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 3.97 x 7.32 x 9.02l, 7.55 #File Name: 09076895071408 pagesthe life and times of Adolf Busch, the "honest musician" | File size: 43.Mb Tully Potter : Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set): 9 of 10 people found the following review helpful. An Exemplary Life and Musical History of the TimesBy Edgar SelfLong awaited, this biography of violinist, composer, quartet and trio leader, teacher, and conductor Adolf Busch (1891-1952), co-founder of the Marlboro School of Music, is a history of the violin, of concerts and chamber-music in the first half of the 20th century. The texts, research notes, copious illustrations, and appendices detail virtually every concert and associate of Busch's life with full descriptions of his musical and personal relations with Reger, Busoni, Tovey, Roentgens and hundreds of others, including those unsympathetic to him such as Furtwaengler, Sibelius, Edwin Fischer, and Elly Ney, for musical or political reasons. Busch's early immigration from Germany and his part in creating the Lucerne Festival and Palestine Symphony Orchestra, precursor of the Israel Philharmonic, before settling in the U.S. -

Symposium Records Cd 1109 Adolf Busch

SYMPOSIUM RECORDS CD 1109 The Great Violinists – Volume 4 ADOLF BUSCH (1891-1952) This compact disc documents the early instrumental records of the greatest German-born musician of this century. Adolf Busch was a legendary violinist as well as a composer, organiser of chamber orchestras, founder of festivals, talented amateur painter and moving spirit of three ensembles: the Busch Quartet, the Busch Trio and the Busch/Serkin Duo. He was also a great man, who almost alone among German gentile musicians stood out against Hitler. His concerts between the wars inspired a generation of music-lovers and musicians; and his influence continued after his death through the Marlboro Festival in Vermont, which he founded in 1950. His associate and son-in-law, Rudolf Serkin (1903-1991) maintained it until his own death, and it is still going strong. Busch's importance as a fiddler was all the greater, because he was the last glory of the short-lived German school; Georg Kulenkampff predeceased him and Hitler's decade smashed the edifice built up by men like Joseph Joachim and Carl Flesch. Adolf Busch's career was interrupted by two wars; and his decision to boycott his native country in 1933, when he could have stayed and prospered as others did, further fractured the continuity of his life. That one action made him an exile, cost him the precious cultural nourishment of his native land and deprived him of his most devoted audience. Five years later, he renounced all his concerts in Italy in protest at Mussolini's anti-semitic laws. -

The Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, Music Director & Conductor Peter Serkin, Piano

PETER LIEBERSON New World Records 80325 Piano Concerto The Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, music director & conductor Peter Serkin, piano Peter Lieberson was born in New York City on October 25, 1946; he lives in Newton Center, Massachusetts, and is currently teaching at Harvard. His Piano Concerto is one of twelve works commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra for its centennial in 1981. From the beginning the piano solo part was intended for Peter Serkin, who gave the first performance with Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra on April 21, 1983, in Symphony Hall, Boston. The youngest of the 12 composers commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra for its centennial, Peter Lieberson grew up in a family where music was ubiquitous. Both his parents were important figures in the artistic world. His father, Goddard Lieberson, himself a trained composer, was perhaps best known as the most influential record-company executive in the artistic world. Peter's mother, under the stage name Vera Zorina, was a ballerina with the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo and later with George Balanchine, before she became known as a specialist in spoken narration. Through a job at New York's classical music radio station WNCN, Lieberson came to know Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson. But the crucial connection came when Copland invited Milton Babbitt to do a program. Until that time the major influence on Lieberson's music was Stravinsky. Now he began to study informally with Babbitt. At Babbitt's suggestion Lieberson chose Columbia when he decided to pursue graduate studies; there he worked with Charles Wuorinen (the third of his three principal teachers would be Donald Martino, with whom he studied at Brandeis University). -

2018-2019 Mostly Music: Franz Schubert

Mostly Music Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Mostly Music Franz Schubert Thursday, March 14th at 7:30 p.m. Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall Dr. Thomas L. McKinley, Host Sonata in a minor D. 821 “Arpeggione” I. Allegro moderato II. Adagio III. Allegretto Eric Varner, bassoon Lisa Leonard, piano Fantasy in f minor, Op. 103, D. 940 for piano four-hands I. Allegro Molto moderato II. Largo III. Scherzo: Allegro vivace IV. Finale: Allegro molto moderato Roberta Rust & Sheng-Yuan Kuan, pianists Intermission Trio No. 2 in E-flat Major Op. 100, D. 929 I. Allegro II. Andante con moto III. Scherzando- allegro moderato IV. Allegro moderato Carol Cole, violin David Cole, cello Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. Unauthorized recording or photography is strictly prohibited Carol Cole’s appearances in the United States, Canada, South America, North Africa, China, and throughout Europe have brought unanimous critical praise for her musical artistry, flawless technique and beautiful tone. “She knows how to capture the hearts of her listeners,” writes the Messaggero of Venice, Italy; “Passionate violin playing, carefully sculpted and crafted,” notes The Pocono Record in Pennsylvania. From Saratoga, New York, the Post Star described her playing as “brilliant, focused and impassioned – exceptional.” The Philadelphia Inquirer reviewed Ms. Cole’s performance at the Mozart- on-the-Square Chamber Music Series as “providing firm, accurate and spirited leadership – her sense of timing and sound (are) musical indeed.” Equally at home as a soloist, chamber musician and orchestra leader, Cole has appeared at major music centers in more than 22 countries and 25 U.S. -

MOZART Piano Quartets Nos. 1 and 2 Clarinet Quintet

111238 bk Szell-Goodman EU 11/10/06 1:50 PM Page 5 MOZART: Quartet No. 1 in G minor for Piano and Strings, K. 478 20:38 1 Allegro 7:27 2 Andante 6:37 MOZART 3 Rondo [Allegro] 6:34 Recorded 18th August, 1946 in Hollywood Matrix nos.: XCO 36780 through 36785. Piano Quartets Nos. 1 and 2 First issued on Columbia 72624-D through 72626-D in album M-773 MOZART: Quartet No. 2 in E flat major for Piano and Strings, K. 493 21:58 Clarinet Quintet 4 Allegro 7:17 AN • G 5 Larghetto 6:44 DM EO 6 O R Allegro 7:57 Also available O G Recorded 20th August, 1946 in Hollywood G E Matrix nos.: XCO 36786 through 36791. Y S Z First issued on Columbia 71930-D through 71932-D in album M-669 N E N L George Szell, Piano E L Members of the Budapest String Quartet B (Joseph Roisman, Violin; Boris Kroyt, Viola; Mischa Schneider, Cello) MOZART: Quintet in A major for Clarinet and Strings, K. 581 27:20 7 Allegro 6:09 8 Larghetto 5:42 9 Menuetto 6:29 0 Allegretto con variazioni 9:00 Recorded 25th April, 1938 in New York City Matrix nos.: BS 022904-2, 022905-2, 022902-2, 022903-1, 022906-1, 022907-1 1 93 gs and CS 022908-2 and 022909-1. 8-1 rdin First issued on Victor 1884 through 1886 and 14921 in album M-452 946 Reco 8.110306 8.110307 Benny Goodman, Clarinet Budapest String Quartet (Joseph Roisman, Violin I; Alexander Schneider, Violin II, Boris Kroyt, Viola; Mischa Schneider, Cello) Budapest String Quartet Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn Joseph Roisman • Alexander Schneider, Violins Boris Kroyt, Viola Mischa Schneider, Cello 8.111238 5 8.111238 6 111238 bk Szell-Goodman EU 11/10/06 1:50 PM Page 2 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791): become more apparent than its failings. -

Annual Report Donors

220015–-16 ANN UAL DONORS REPORT CURTIS IN S TIT UTE O F MUSIC DONORS 2015–16 2 LIFETIME DONORS $1 MILLION AND ABOVE We extend our deep gratitude to the extraordinary individuals and organizations whose cumulative giving exceeds $1 million as of May 31, 2016. Their support helps ensure the continuation of our tuition-free policy. Anonymous The Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation Nina and Billy Albert Lester Lanin+ The Allerton Foundation H. F. “Gerry” and Marguerite Lenfest The Annenberg Foundation Gie and Lisa Liem◊ Herbert R. and Evelyn Axelrod Sueyun and Gene Locks Maryjane Mayhew Barton*+ Markow-Totevy Foundation Mrs. Cary William Bok Betty and James Matarese Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz John H. McFadden and Lisa D. Kabnick Vera D. Bruestle+ J. J. Medveckis Foundation William D. Burns*+ Neubauer Family Foundation Ernestine Bacon Cairns Trust Nina Maria Arts and Culture Foundation Commonwealth of Pennsylvania William Penn Foundation L. Daniel Dannenbaum+ and Katherine Hall The Pew Charitable Trusts Joseph*+ and Yvonne*+ Druian Suzanne Hanson Poole*+ Lester L.+ and Judith M.+ Eisner Dr. Milton L. Rock Joseph and Marie Field Aaron Rosand* Fondation Charidu/Nina Baroness von Maltzahn Mark and Robin Rubenstein The Edwin B. Garrigues Foundation H. Shaw Roberts Scholl+ The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation David*+ and Jane+ Schwartz Bruce Jay Gould, M.D. Arthur+ and Hilda+ Stander Haas Charitable Trusts Dorothy Richard Starling Foundation Edna L. Harkness*+ Penelope P. Watkins Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser The Helen F. Whitaker Fund Ruth Duskin Heller+ Ruth W.+ and A. Morris Williams Jr. Alan and Nancy Hirsig Jack Wolgin+ William and Nina Hollis Foundation Mary Louise Curtis Bok Zimbalist+ * alumnus/alumna ◊ Curtis parent + deceased DONORS 2015–16 3 LEADERSHIP SUPPORT We recognize the following donors for their exceptional combined gifts as of May 31, 2016, including donations toward the Curtis Annual Fund, endowed funds, the Amadeus Affair gala, and special programs.