The KGB in Kremlin Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ukrainian Weekly 1985

Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.. a fraternal non-profit association! rainian Weekly Vol. Llll No. 6 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 1985 25 cents Congressmen urge humane treatment CSCE nominates lights activists for political prisoners' families for 1985 Nobel Peace Prize WASHINGTON - Ninety year earlier. His father was sentenced in congressmen have co-signed a letter late 1974 to 10 years' labor camp and urging Soviet leader Konstantin exile. Chernenko to provide "more humane In the January 29 letter, the treatment" for members of two families congressmen cited recent reports that incarcerated for their political activities. authorities had interrupted The families- are Ukrainian human- correspondence between the Kovalevs rights activist Mykola Rudenko and his and banned visits between Mr. Kovalev wife, Raisa, and political prisoners Ivan and his wife. Kovalev. his wife. Tatiana Osipova. and They also urged that visits and his father. Sergei Kovalev, who is in correspondence be resumed between exile. Mr. Rudenko and his wife, and that Mr. Rudenko. 63, was a founding both families be given "proper medical member in 1976 of the Ukrainian attention." According to the letter, Ms. Helsinki Group, which was established Osipova and Sergei Kovalev are "in to monitor Soviet compliance with the need of hospitali?ation." Helsinki Accords on human rights and security in Europe. In 1978 he was The congressmen said they had Nominees for the 1985 information indicating that the two sentenced tasever+years-inalaber-eamp - Nobel Peace Prize: (clock and five years' internal exile, which he is families were "not being treated in wise from top left) My now serving in Gorno-Altayskaya accordance with the spirit of the kola Rudenko of the Autonomous Oblast. -

Questions to Russian Archives – Short

The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative RWI-70 Formal Request to the Russian Government and Archival Authorities on the Raoul Wallenberg Case Pending Questions about Documentation on the 1 Raoul Wallenberg Case in the Russian Archives Photo Credit: Raoul Wallenberg’s photo on a visa application he filed in June 1943 with the Hungarian Legation, Stockholm. Source: The Hungarian National Archives, Budapest. 1 This text is authored by Dr. Vadim Birstein and Susanne Berger. It is based on the paper by V. Birstein and S. Berger, entitled “Das Schicksal Raoul Wallenbergs – Die Wissenslücken.” Auf den Spuren Wallenbergs, Stefan Karner (Hg.). Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2015. S. 117-141; the English version of the paper with the title “The Fate of Raoul Wallenberg: Gaps in Our Current Knowledge” is available at http://www.vbirstein.com. Previously many of the questions cited in this document were raised in some form by various experts and researchers. Some have received partial answers, but not to the degree that they could be removed from this list of open questions. 1 I. FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) Archival Materials 1. Interrogation Registers and “Prisoner no. 7”2 1) The key question is: What happened to Raoul Wallenberg after his last known presence in Lubyanka Prison (also known as Inner Prison – the main investigation prison of the Soviet State Security Ministry, MGB, in Moscow) allegedly on March 11, 1947? At the time, Wallenberg was investigated by the 4th Department of the 3rd MGB Main Directorate (military counterintelligence); -

The Siloviki in Russian Politics

The Siloviki in Russian Politics Andrei Soldatov and Michael Rochlitz Who holds power and makes political decisions in contemporary Russia? A brief survey of available literature in any well-stocked bookshop in the US or Europe will quickly lead one to the answer: Putin and the “siloviki” (see e.g. LeVine 2009; Soldatov and Borogan 2010; Harding 2011; Felshtinsky and Pribylovsky 2012; Lucas 2012, 2014 or Dawisha 2014). Sila in Russian means force, and the siloviki are the members of Russia’s so called “force ministries”—those state agencies that are authorized to use violence to respond to threats to national security. These armed agents are often portrayed—by journalists and scholars alike—as Russia’s true rulers. A conventional wisdom has emerged about their rise to dominance, which goes roughly as follows. After taking office in 2000, Putin reconsolidated the security services and then gradually placed his former associates from the KGB and FSB in key positions across the country (Petrov 2002; Kryshtanovskaya and White 2003, 2009). Over the years, this group managed to disable almost all competing sources of power and control. United by a common identity, a shared worldview, and a deep personal loyalty to Putin, the siloviki constitute a cohesive corporation, which has entrenched itself at the heart of Russian politics. Accountable to no one but the president himself, they are the driving force behind increasingly authoritarian policies at home (Illarionov 2009; Roxburgh 2013; Kasparov 2015), an aggressive foreign policy (Lucas 2014), and high levels of state predation and corruption (Dawisha 2014). While this interpretation contains elements of truth, we argue that it provides only a partial and sometimes misleading and exaggerated picture of the siloviki’s actual role. -

Bul NKVD AJ.Indd

The NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 Anthology of the international conference Bratislava 14. – 16. 11. 2007 Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Nation´s Memory Institute BRATISLAVA 2008 Anthology was published with kind support of The International Visegrad Fund. Visegrad Fund NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Cen- tral and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 14 – 16 November, 2007, Bratislava, Slovakia Anthology of the international conference Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Published by Nation´s Memory Institute Nám. SNP 28 810 00 Bratislava Slovakia www.upn.gov.sk 1st edition English language correction Anitra N. Van Prooyen Slovak/Czech language correction Alexandra Grúňová, Katarína Szabová Translation Jana Krajňáková et al. Cover design Peter Rendek Lay-out, typeseting, printing by Vydavateľstvo Michala Vaška © Nation´s Memory Institute 2008 ISBN 978-80-89335-01-5 Nation´s Memory Institute 5 Contents DECLARATION on a conference NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 ..................................................................9 Conference opening František Mikloško ......................................................................................13 Jiří Liška ....................................................................................................... 15 Ivan A. Petranský ........................................................................................ -

Download Cartoons and Descriptions

1. Creator: Stephen Sack Title: “See No… Hear No… Speak No…” Publication: Ft. Wayne Journal Publication Date: Unknown, 1978-1979 Description: In 1964 Leonid Brezhnev took over as the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Part of the Soviet Union after Nikita Khrushchev was removed from power. He presided over the USSR from 1964 until his death in 1982. Some of Brezhnev’s early changes were to remove the liberalizing reforms made of Khrushchev. Cultural freedom was limited and the secret service, the KBG, regained power. In 1973, the Soviet Union entered an era of economic stagnation which led to unhappiness among the Soviet people. Brezhnev continued the policy of détente with the United States, limiting arms but at the same time building up Soviet military strength. Source: Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum: Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year ed. Charles Brooks. Pelican Publishing Press, Gretna, 1979 Folder: Cartoons Bezbatchenko 2. Creator: Mike Keffe Title: Untitled Publication: Denver Post Publication Date: Unknown, 1980- 1981 Description: Elections were held in the USSR and the United States in 1979 and 1980 respectively. The 1980 presidential campaign was between incumbent Democrat Jimmy Carter and Republican candidate, Ronald Reagan. The election was held on November 4, 1980. Reagan won the electoral college vote by a landslide. In the Soviet Union, elections were held but for appearances only. Vladimir Lenin and the other Bolshevik leaders dissolved the Constituent Assembly in 1918. Under Stalin’s rule the position of General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party became synonymous with “leader of the Soviet Union.” In 1980, the government was controlled by nonelected Communist Politburo members, the Central Committee and a parliament type group called the Supreme Soviet, who only met briefly throughout the year. -

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation J. MICHAEL WALLER "They write I'm the mafia's godfather. It was Vladimir Ilich Lenin who was the real organizer of the mafia and who set up the criminal state." -Otari Kvantrishvili, Moscow organized crime leader.l "Criminals Nave already conquered the heights of the state-with the chief of the KGB as head of a mafia group." -Former KGB Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin.2 Introduction As the United States and Russia launch a Great Crusade against organized crime, questions emerge not only about the nature of joint cooperation, but about the nature of organized crime itself. In addition to narcotics trafficking, financial fraud and racketecring, Russian organized crime poses an even greater danger: the theft and t:rafficking of weapons of mass destruction. To date, most of the discussion of organized crime based in Russia and other former Soviet republics has emphasized the need to combat conven- tional-style gangsters and high-tech terrorists. These forms of criminals are a pressing danger in and of themselves, but the problem is far more profound. Organized crime-and the rarnpant corruption that helps it flourish-presents a threat not only to the security of reforms in Russia, but to the United States as well. The need for cooperation is real. The question is, Who is there in Russia that the United States can find as an effective partner? "Superpower of Crime" One of the greatest mistakes the West can make in working with former Soviet republics to fight organized crime is to fall into the trap of mirror- imaging. -

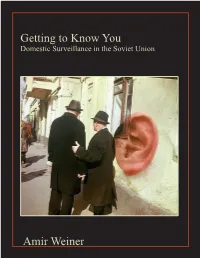

Getting to Know You. the Soviet Surveillance System, 1939-1957

Getting to Know You Domestic Surveillance in the Soviet Union Amir Weiner Forum: The Soviet Order at Home and Abroad, 1939–61 Getting to Know You The Soviet Surveillance System, 1939–57 AMIR WEINER AND AIGI RAHI-TAMM “Violence is the midwife of history,” observed Marx and Engels. One could add that for their Bolshevik pupils, surveillance was the midwife’s guiding hand. Never averse to violence, the Bolsheviks were brutes driven by an idea, and a grandiose one at that. Matched by an entrenched conspiratorial political culture, a Manichean worldview, and a pervasive sense of isolation and siege mentality from within and from without, the drive to mold a new kind of society and individuals through the institutional triad of a nonmarket economy, single-party dictatorship, and mass state terror required a vast information-gathering apparatus. Serving the two fundamental tasks of rooting out and integrating real and imagined enemies of the regime, and molding the population into a new socialist society, Soviet surveillance assumed from the outset a distinctly pervasive, interventionist, and active mode that was translated into myriad institutions, policies, and initiatives. Students of Soviet information systems have focused on two main features—denunciations and public mood reports—and for good reason. Soviet law criminalized the failure to report “treason and counterrevolutionary crimes,” and denunciation was celebrated as the ultimate civic act.1 Whether a “weapon of the weak” used by the otherwise silenced population, a tool by the regime -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

Twenty-Seventh Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

TMUN TWENTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION MARCH 1986 COMITTEEE DIRECTOR VICE DIRECTORS MODERATOR SIERRA CHOW NATHALIA HERRERA DAVIS HAUGEN TESSA DI VIZIO THE TWENTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS OF THE TMUN COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION A Letter from Your Director 2 Topic A: Economic Reform and Institutional Restructuring 3 Uskorenie 3 Glasnost 6 Perestroika 7 Questions to Consider 9 Topic B: National Movements and Satellite States 10 Russian Nationalism 10 Satellite States 11 Hungarian Revolution, 1956 12 Prague Spring Czechoslovakia, 1968 13 Poland Solidarity, 1980 14 The Baltics 17 Kazakhstan 19 Questions to Consider 21 Topic C: Foreign Policy Challenges 22 The Brezhnev Era 22 Gorbachev’s “New Thinking” 23 American Relations 25 Soviet Involvement in Afghanistan 26 Turning Point 28 Questions to Consider 30 Characters 31 Advice for Research and Preparation 36 General Resources 37 Topic A Key Resources 37 Topic B Key Resources 37 Topic C Key Resources 38 Bibliography 39 Topic A 39 Topic C 41 1 THE TWENTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS OF THE TMUN COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION A LETTER FROM YOUR DIRECTOR Dear Delegates, Welcome to the 27thCongress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. This event represents a turning point in the Soviet Union’s history, as Mikhail Gorbachev, a champion of reform and reorientation, leads his first Congress as General Secretary. My name is Sierra Chow, and I will be your Director for the conference. I am a third-year student at the University of Toronto, enrolled in Political Science, Psychology, and Philosophy. Should you have any questions about the topics, the committee, the conference, or University of Toronto in general, please reach out to me via email and I will do my best to help. -

Reform and Human Rights the Gorbachev Record

100TH-CONGRESS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES [ 1023 REFORM AND HUMAN RIGHTS THE GORBACHEV RECORD REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES BY THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE MAY 1988 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1988 84-979 = For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE STENY H. HOYER, Maryland, Chairman DENNIS DeCONCINI, Arizona, Cochairman DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida FRANK LAUTENBERG, New Jersey EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts TIMOTHY WIRTH, Colorado BILL RICHARDSON, New Mexico WYCHE FOWLER, Georgia EDWARD FEIGHAN, Ohio HARRY REED, Nevada DON RITTER, Pennslyvania ALFONSE M. D'AMATO, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey JOHN HEINZ, Pennsylvania JACK F. KEMP, New York JAMES McCLURE, Idaho JOHN EDWARD PORTER, Illinois MALCOLM WALLOP, Wyoming EXECUTIvR BRANCH HON. RICHARD SCHIFIER, Department of State Vacancy, Department of Defense Vacancy, Department of Commerce Samuel G. Wise, Staff Director Mary Sue Hafner, Deputy Staff Director and General Counsel Jane S. Fisher, Senior Staff Consultant Michael Amitay, Staff Assistant Catherine Cosman, Staff Assistant Orest Deychakiwsky, Staff Assistant Josh Dorosin, Staff Assistant John Finerty, Staff Assistant Robert Hand, Staff Assistant Gina M. Harner, Administrative Assistant Judy Ingram, Staff Assistant Jesse L. Jacobs, Staff Assistant Judi Kerns, Ofrice Manager Ronald McNamara, Staff Assistant Michael Ochs, Staff Assistant Spencer Oliver, Consultant Erika B. Schlager, Staff Assistant Thomas Warner, Pinting Clerk (11) CONTENTS Page Summary Letter of Transmittal .................... V........................................V Reform and Human Rights: The Gorbachev Record ................................................ -

Bulletin 10-Final Cover

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN Issue 10 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. March 1998 Leadership Transition in a Fractured Bloc Featuring: CPSU Plenums; Post-Stalin Succession Struggle and the Crisis in East Germany; Stalin and the Soviet- Yugoslav Split; Deng Xiaoping and Sino-Soviet Relations; The End of the Cold War: A Preview COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN 10 The Cold War International History Project EDITOR: DAVID WOLFF CO-EDITOR: CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN ADVISING EDITOR: JAMES G. HERSHBERG ASSISTANT EDITOR: CHRISTA SHEEHAN MATTHEW RESEARCH ASSISTANT: ANDREW GRAUER Special thanks to: Benjamin Aldrich-Moodie, Tom Blanton, Monika Borbely, David Bortnik, Malcolm Byrne, Nedialka Douptcheva, Johanna Felcser, Drew Gilbert, Christiaan Hetzner, Kevin Krogman, John Martinez, Daniel Rozas, Natasha Shur, Aleksandra Szczepanowska, Robert Wampler, Vladislav Zubok. The Cold War International History Project was established at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C., in 1991 with the help of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and receives major support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Smith Richardson Foundation. The Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to disseminate new information and perspectives on Cold War history emerging from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side”—the former Communist bloc—through publications, fellowships, and scholarly meetings and conferences. Within the Wilson Center, CWIHP is under the Division of International Studies, headed by Dr. Robert S. Litwak. The Director of the Cold War International History Project is Dr. David Wolff, and the incoming Acting Director is Christian F. -

The Diary of Anatoly S. Chernyaev 1986

The Diary of Anatoly S. Chernyaev 1986 Donated by A.S. Chernyaev to The National Security Archive Translated by Anna Melyakova Edited by Svetlana Savranskaya http://www.nsarchive.org Translation © The National Security Archive, 2007 The Diary of Anatoly S. Chernyaev, 1986 http://www.nsarchive.org January 1st, 1986. At the department1 everyone wished each other to celebrate the New Year 1987 “in the same positions.” And it is true, at the last session of the CC (Central Committee) Secretariat on December 30th, five people were replaced: heads of CC departments, obkom [Oblast Committee] secretaries, heads of executive committees. The Politizdat2 director Belyaev was confirmed as editor of Soviet Culture. [Yegor] Ligachev3 addressed him as one would address a person, who is getting promoted and entrusted with a very crucial position. He said something like this: we hope that you will make the newspaper truly an organ of the Central Committee, that you won’t squander your time on petty matters, but will carry out state and party policies... In other words, culture and its most important control lever were entrusted to a Stalinist pain-in-the neck dullard. What is that supposed to mean? Menshikov’s case is also shocking to me. It is clear that he is a bastard in general. I was never favorably disposed to him; he was tacked on [to our team] without my approval. I had to treat him roughly to make sure no extraterritoriality and privileges were allowed in relation to other consultants, and even in relation to me (which could have been done through [Vadim] Zagladin,4 with whom they are dear friends).