If There's No "Fat Lady," When Is the Opera Over? an Exploration of Changing Physical Image Standards in Present-Day Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Katalog EMI Classics Oraz Virgin Classics

Katalog EMI Classics oraz Virgin Classics Tytuł: Vinci L'Artaserse ICPN: 5099960286925 KTM: 6028692 Data Premiery: 01.10.2012 Data nagrania: styczeń 2012 Main Artists: Diego Fasolis/Philippe Jaroussky/Max Emanuel Cencic/Franco Fagioli/Valer Barna-Sabadus/Yuriy Mynenko/Daniel Behle/Coro della Radiotelevisione svizzera, Lugano/Concerto Köln Kompozytor: Leonardo Vinci 3 CD POLSKA PREMIERA Tytuł: Feelhermony ICPN:5099901770827 KRM:0177082 Data Premiery: 09.10.2012 Data Nagrania: 2012 Main Artists: KROKE, Sinfonietta Cracovia, Anna Maria Jopek, Sławek Berny Kompozytor: KROKE Aranżancje: Krzysztof Herdzin 1 CD Tytuł: Rodgers & Hammerstein at the Movies ICPN: 5099931930123 KTM: 3193012 Data Premiery: 01.10.2012 Data nagrania: styczeń 2012 Main Artists: John Wilson, John Wilson Orchestra, Sierra Boggess, Anna Jane Casey, Joyce DiDonato, Maria Ewing, Julian Ovenden, David Pittsinger, Maida Vale Singers Kompozytor: Rodgers & Hammerstein 1 CD Tytuł: Sound the Trumpet - Royal Music of Purcell and Handel ICPN: 5099944032920 KTM: 4403292 Data Premiery: 15.10.2012 Data nagrania: styczeń 2012 Main Artists: Alison Balsom, The English Concert, Pinnock Trevor Kompozytor: Purcell, Haendel 1 CD Tytuł: Dvorak: Symphony No.9 & Cello Concerto ICPN: 5099991410221 KTM: 9141022 Data Premiery: 08.10.2012 Data Nagrania: styczeń 2012 Main Artists: Antonio Pappano Kompozytor: Antonin Dvorak 2 CD Tytuł: Drama Queens ICPN: 5099960265425 KTM: 6026542 Data Premiery: 01.10.2012 Main Artists: Joyce DiDonato/Il Complesso Barocco/Alan Curtis Kompozytor: Various Artists 1 CD -

A1ib000000d8uszaaz.Pdf

KOOR EN ORKEST VAN DE MUNT Ver A i U I T DE MUNT 14 J A N U A R I 92 KOOR EN ORKEST VAN DE MUNT muzikale leiding Antonio Pappano koorleider Johannes Mikkelsen Solisten Margaret Jane Wray, sopraan Florence Quivar, mezzo Richard Greager, tenor Carlo Colombara, bas P rogr a mma GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813-1901) MESSA DA REQUIEM Requiem en Kyrie (a quattro voci soliste e coro) Dies Irae Dies Irae (coro) Tuba mirum (basso e coro) Liber scriptus (mezzosoprano e coro) Quid sum mlser (soprano, mezzosoprano e coro) Rex tremendae (quartetto e coro) Recordare (soprano e mezzosoprano) Ingemisco (solo pet tenore) Confutatis (basso e coro) Lacrymosa (quartetto e coro) Domine Jesu (offertorio a quattro voci soliste) Sanctus (fuga a due cori) Agnus Dei (soprano, mezzosoprano e coro) Lux Aeterna inleidend gesprek door Magda de Meester Foyer 19.15 uur (mezzosoprano, tenore e basso) aanvang concert 20.00 uur Libera Me geen pauze (soprano e coro) einde concert omstreeks 21 .30 uur ANTONIO PAPPANO Antonio Pappano werd in Londen geboren uit Italiaanse ouders. Hij studeerde piano, compositie en orkestdirectie bij Norma Verrilli, Arnold Franchetti en Gustav Meier. Van in het begin van zijn carrière ontwikkelde Antonio Pappano een liefde voor opera en theater. Hij heeft in talrijke operahuizen gewerkt, zoals de New York City Opera, de Opera van San Diego, het Liceu in Barcelona en de Opera van Frankfurt. Hij onderhield nauwe banden met de Lyric Opera van Chicago en het Festival van Bayreuth waar hij assistent was van Daniel Barenboim voor 'Tristan und Isolde', 'Parsifal' en de 'Ring des Nibelungen'. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

TURANDOT Cast Biographies

TURANDOT Cast Biographies Soprano Martina Serafin (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut as the Marshallin in Der Rosenkavalier in 2007. Born in Vienna, she studied at the Vienna Conservatory and between 1995 and 2000 she was a member of the ensemble at Graz Opera. Guest appearances soon led her to the world´s premier opera stages, including at the Vienna State Opera where she has been a regular performer since 2005. Serafin´s repertoire includes the role of Lisa in Pique Dame, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. Upcoming engagements include Elsa von Brabant in Lohengrin at the Opéra National de Paris and Abigaille in Nabucco at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Dramatic soprano Nina Stemme (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut in 2004 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, and has since returned to the Company in acclaimed performances as Brünnhilde in 2010’s Die Walküre and in 2011’s Ring cycle. Since her 1989 professional debut as Cherubino in Cortona, Italy, Stemme’s repertoire has included Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Mimi in La Bohème, Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, the title role of Suor Angelica, Euridice in Orfeo ed Euridice, Katerina in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, Marguerite in Faust, Agathe in Der Freischütz, Marie in Wozzeck, the title role of Jenůfa, Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Elsa in Lohengrin, Amelia in Un Ballo in Machera, Leonora in La Forza del Destino, and the title role of Aida. -

BAM and New York City Opera Present US Premiere of Anna Nicole, an Opera by Mark-Anthony Turnage with Libretto by Richard Thomas—September 17 to 28

BAM and New York City Opera present US premiere of Anna Nicole, an opera by Mark-Anthony Turnage with libretto by Richard Thomas—September 17 to 28 Anna Nicole launches BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival American Express is the BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival Sponsor BAM and New York City Opera present Anna Nicole Composed by Mark-Anthony Turnage Libretto by Richard Thomas Directed by Richard Jones Conducted by Steven Sloane Scenic design by Miriam Buether Costume design by Nicky Gillibrand Lighting design by Mimi Jordan Sherin & D.M. Wood Choreography by Aletta Collins Line producer and Soloist Casting by Elaine Padmore Additional Casting by Telsey + Company, Tiffany Little Canfield, CSA Anna Nicole was commissioned by the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, and premiered there in February 2011 BAM Howard Gilman Opera House (30 Lafayette Ave) Sep 17–28 at 7:30pm Tickets: $25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150 (weekday); $35, 60, 85, 115, 145, 175 (weekend) Master Class: Lyrics, Libretto, and Luck with Richard Thomas Sep 12 at 3pm, BAM Fisher Leavitt Workshop (321 Ashland Pl) Tickets: $25 Talk: The Making of Anna Nicole, with Mark-Anthony Turnage, Richard Thomas, and Richard Jones, moderated by Elaine Padmore. Sept 16 at 7pm, BAMcafé (30 Lafayette Ave) Tickets: $15 ($7.50 for Friends of BAM) Anna Nicole: An Opening Affair, Sep 17, post-show celebration Tickets: BAM Patron Services, 718.636.4182 or [email protected] Brooklyn, NY/Aug 8, 2013—The 2013 Next Wave Festival launches with the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) and New York City Opera co-production of Anna Nicole, an opera by composer Mark- Anthony Turnage and librettist Richard Thomas based on the flamboyant life and tragic death of Anna Nicole Smith. -

Web Site Leads to GOP Complaint

Johnny Appleseed Linden students celebrated the American legend of Johnny Appleseed last week. Serving Linden, Roselle, Rahway and Elizabeth Page 3 LINDEN, N.J WWW.LOCALSOURCE.COM 75 CENTS VOL. 89 NO. 39 THURSDAY OCTOBER 5, 2006 Web site leads to GOP complaint By Kitty Wilder paid a total of $9 for two domain Kennedy said he was not aware ofthe site, Enforcement Commission said it is Managing Editor CAMPAIGN UPDATE names. The second domain name was adding, “It’s nothing I’m supporting.” not the commission’s policy to con RAHWAY — Local Republicans used to create a second Rahway He said Devine is not a consultant firm or deny complaints filed. have filed a complaint with the state Republicans for Kennedy Web site at for his campaign, but he is paid for Web sites have become common in alleging a Democratic campaign Lund. It did not contain a disclaimer. www.timeforchange2006.net. printing services. campaigning and are treated like other worker created a Web site intended to The site, which did not include a The address is similar to another Devine said he is a consultant for campaign literature, Davis said. They misrepresent their party. disclaimer, contained a similar address Bodine for Mayor address, www.time- Kennedy, adding, “I advise the Demo are required to include a disclaimer The complaint, filed Friday with to the homepage for the campaign rep forchange2006.com. cratic Party on strategic and tactical clarifying who paid for the site. the state Election Law Enforcement resenting the council candidates and Cassio said the similarity between measures to promote their candidates The commission follows a standard Commission, alleges the group Rah mayoral candidate Larry Bodine. -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

Wagner Inlay 10/6/04 10:43 Am Page 1 NAXOS

555789 Wagner inlay 10/6/04 10:43 am Page 1 NAXOS The present recording of scenes from Tristan und Isolde and of the Immolation Scene from Götterdämmerung features three distinguished interpreters of Wagner, acclaimed for performances in the major opera houses of Europe and America. Margaret Jane Wray has performed with some of the most important musical figures of our day, including Daniel Barenboim, Maris Janssons and Seiji Ozawa and 8.555789 enjoys a busy career as a concert artist in addition to her varied operatic performances. Included on this WAGNER: disc is the rarely recorded 1862 concert ending to the Love Duet from Tristan und Isolde. DDD Richard 8.555789 WAGNER Playing Time (1813-1883) 76:39 Scenes from Tristan and Götterdämmerung TRISTAN UND ISOLDE, ACT 2, SCENES 1 & 2 7 Isolde . Margaret Jane Wray, Soprano 47313 Tristan . John Horton Murray, Tenor Brangäne . Nancy Maultsby, Mezzo-Soprano 1 Einleitung (Introduction) 1:58 ! O sink hernieder, Nacht der Liebe 2:36 57892 2 Hörst du sie noch? 2:29 @ Barg im Busen uns sich die Sonne 2:42 3 Nicht Hörnerschall tönt so hold 6:09 # Einsam wachend in der Nacht 2:43 4 Dein Werk? O tör’ge Magd! 3:56 $ Lausch, Geliebter! 1:46 5 Isolde! Tristan! Geliebte(r)! 2:57 % Unsre Liebe? Tristans Liebe? 2:10 6 Wie lange fern! Wie fern so lang! 1:19 ^ Doch unsre Liebe 1:58 4 7 Dem Tage! Dem Tage 4:51 & So stürben wir, um ungetrennt 2:57 www.naxos.com Made in the EU English translations Gesangtexte auf Deutsch • German sung texts with Booklet notes in English • Kommentar und h 8 O eitler Tagesknecht! 2:15 * Soll ich lauschen? 1:41 & 9 In deiner Hand den süssen Tod 1:56 ( O ew’ge Nacht, süsse Nacht!* 5:43 g 0 Doch es rächte sich der 2004 Naxos Rights International Ltd. -

The KF International Marcella Sembrich International Voice

The KF is excited to announce the winners of the 2015 Marcella Sembrich International Voice Competition: 1st prize – Jakub Jozef Orlinski, counter-tenor; 2nd prize – Piotr Buszewski, tenor; 3rd prize – Katharine Dain, soprano; Honorable Mention – Marcelina Beucher, soprano; Out of 92 applicants, 37 contestants took part in the preliminary round of the competition on Saturday, November 7th, with 9 progressing into the final round on Sunday, November 8th at Ida K. Lang Recital Hall at Hunter College. This year's competition was evaluated by an exceptional jury: Charles Kellis (Juilliard, Prof. emeritus) served as Chairman of the Jury, joined by Damon Bristo (Vice President and Artist Manager at Columbia Artists Management Inc.), Markus Beam (Artist Manager at IMG Artists) and Dr. Malgorzata Kellis who served as a Creative Director and Polish song expert. About the KF's Marcella Sembrich Competition: Marcella Sembrich-Kochanska, soprano (1858-1935) was one of Poland's greatest opera stars. She appeared during the first season of the Metropolitan Opera in 1883, and would go on to sing in over 450 performances at the Met. Her portrait can be found at the Metropolitan Opera House, amongst the likes of Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo, and Giuseppe Verdi. The KF's Marcella Sembrich Memorial Voice Competition honors the memory of this great Polish artist, with the aim of popularizing Polish song in the United States, and discovering new talents (aged 18-35) in the operatic world. This year the competition has turned out to be very successful, considering that the number of contestants have greatly increased and that we have now also attracted a number of International contestants from Japan, China, South Korea, France, Canada, Puerto Rico and Poland. -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

2020-21-Brochure.Pdf

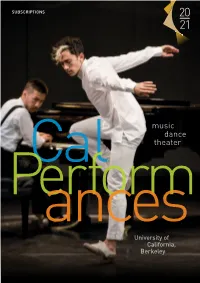

SUBSCRIPTIONS 20 21 music dance Ca l theater Performances University of California, Berkeley Letter from the Director Universities. They exist to foster a commitment to knowledge in its myriad facets. To pursue that knowledge and extend its boundaries. To organize, teach, and disseminate it throughout the wider community. At Cal Performances, we’re proud of our place at the heart of one of the world’s finest public universities. Each season, we strive to honor the same spirit of curiosity that fuels the work of this remarkable center of learning—of its teachers, researchers, and students. That’s why I’m happy to present the details of our 2020/21 Season, an endlessly diverse collection of performances rivaling any program, on any stage, on the planet. Here you’ll find legendary artists and companies like cellist Yo-Yo Ma, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the Mark Morris Dance Group, pianist Mitsuko Uchida, and singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo. And you’ll discover a wide range of performers you might not yet know you can’t live without—extraordinary, less-familiar talent just now emerging on the international scene. This season, we are especially proud to introduce our new Illuminations series, which aims to harness the power of the arts to address the pressing issues of our time and amplify them by shining a light on developments taking place elsewhere on the Berkeley campus. Through the themes of Music and the Mind and Fact or Fiction (please see the following pages for details), we’ll examine current groundbreaking work in the university’s classrooms and laboratories. -

The Inventory of the Deborah Voigt Collection #1700

The Inventory of the Deborah Voigt Collection #1700 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Voigt, Deborah #1700 6/29/05 Preliminary Listing I. Subject Files. Box 1 A Chronological files; includes printed material, photographs, memorabilia, professional material, other items. 1. 1987-1988. [F. 1] a. Mar. 1987; newsletters of The Riverside Opera Association, Verdi=s AUn Ballo in Maschera@ (role of Amelia). b. Apr. 1987; program from Honolulu Symphony (DV on p. 23). c. Nov. 1987; program of recital at Thorne Hall. d. Jan. 1988; program of Schwabacher Debut Recitals and review clippings from the San Francisco Examiner and an unknown newspaper. e. Mar. 1988; programs re: DeMunt=s ALa Monnaie@ and R. Strauss=s AElektra@ (role of Fünfte Magd). f. Apr. 1988; magazine of The Minnesota Orchestra Showcase, program for R. Wagner=s ADas Rheingold@ (role of Wellgunde; DV on pp. 19, 21), and review clippings from the Star Tribune and the St. Paul Pioneer Press Dispatch. g. Sep. - Oct. 1988; programs re: Opera Company of Philadelphia and the International Voice Competition (finalist competition 3; DV on p. 18), and newspaper clippings. 2. 1989. [F. 2] a. DV=s itineraries. (i) For Jan. 4 - Feb. 9, TS. (ii) For the Johann Strauss Orchestra on Vienna, Jan. 5 - Jan. 30, TS, 7 p. b. Items re: California State, Fullerton recital. (i) Copy of Daily Star Progress clipping, 2/10/89. (ii) Compendium of California State, Fullerton, 2/13/89. (iii) Newspaper clipping, preview, n.d. (iv) Orange County Register preview, 2/25/89. (v) Recital flyer, 2/25/89. (vi) Recital program, program notes, 2/25/89.