Urbanism Under Google: Lessons from Sidewalk Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automated Vehicles Tactical Plan

Attachment 1: Automated Vehicles Tactical Plan IE8.7 - Attachment 1 AUTOMATED VEHICLES TACTICAL PLANDRAFT INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK DRAFT ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document is the result of guidance, feedback and support from a number of individuals and organizations. In the development of this Automated Vehicles Tactical Plan, the City of Toronto hosted many stakeholder workshops and one-on-one meetings, consulted panels, and provided an open call for feedback via surveys and public posting. Responses were provided by academic institutions, industry representatives, community associations, City staff, advocacy groups, neighbouring municipalities, members of the public and international experts – among other stakeholders. A special thank you to the 2018 Toronto Planning Review Panel, the 2019 Accessibility Advisory Committee, and the 2019 Expert Review Panel hosted by the Ontario Centres of Excellence for their detailed feedback on the AV Tactical Plan. Expert Review Panel Members Emiko Atherton Anthony Townsend Director National Complete Streets Principal Consultant and Author, Bits Coalition, Smart Growth America and Atoms LLC (New York City, NY) (Washington, DC) Dr. Tom Vöge Ann Cavoukian Policy Analyst Intelligent Transport Distinguished Expert-in-Residence, Systems, Organization for Economic Privacy by Design Centre of Cooperation and Development – Excellence, Ryerson University International Transport Forum (Paris, (Toronto, ON) France) Rita Excell Bryant Walker Smith Executive Director, Australia and New Assistant Professor School of -

25 Actual Hits from the 80S That Mr. Moderator Liked

25 Actual Hits From The 80s That Mr. Moderator Liked Even During Those Days When He Was "Too Cool for School": Song Artist Suggested by: 1.) Don't You Want Me Human League Mr. Moderator 2.) True Spandau Ballet Mr. Moderator 3.) Missing You John Waite Mr. Moderator 4.) Like a Virgin Madonna Mr. Moderator 5.) Temptation New Order Mr. Moderator 6.) What You Need INXS Mr. Moderator 7.) Tainted Love Soft Cell funoka 8.) I Melt with You Modern English Mr. Moderator 9.) Faith George Michael Mr. Moderator 10.) She Drives Me Crazy Fine Young Cannibals Mr. Moderator 11.) Always Something There to... Naked Eyes Ohmstead 12.) Age of Consent New Order Slim Jade 13.) Rhythm is Gonna Get You Gloria Estefan Slim Jade 14.) (You Gotta) Fight for Your Right... Beastie Boys Mr. Moderator 15.) So Alive Love and Rockets andyr 16.) Looking for a New Love Jodi Watley jeangray 17.) Pass the Dutchie Musical Youth alexmagic 18.) Antmusic Adam and the Ants alexmagic 19.) Goody Two Shoes Adam Ant alexmagic 20.) Love Plus One Haircut 100 andyr 21.) Paper in Fire John Cougar Melloncamp Mr. Moderator 22.) (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League alexmagic 23.) Material Girl Madonna Mr. Moderator 24.) Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) Eurythmics alexmagic 25.) Church of the Poison Mind Culture Club Mr. Moderator Rock Town Hall 80s Master Playlist Song Artist Suggested by: 1.) A Message to You Rudy The Specials ladymisskirroyale 2.) A New England Kristy MacColl Suburban kid 3.) AEIOU Sometimes Y Ebn-Ozn jeangray 4.) Addicted to Love Robert Palmer ladymisskirroyale 5.) Ah! Leah! Donnie Iris Sgt. -

Cedars, January 21, 2000 Cedarville College

Masthead Logo Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Cedars 1-21-2000 Cedars, January 21, 2000 Cedarville College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Organizational Communication Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a platform for archiving the scholarly, creative, and historical record of Cedarville University. The views, opinions, and sentiments expressed in the articles published in the university’s student newspaper, Cedars (formerly Whispering Cedars), do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The uthora s of, and those interviewed for, the articles in this paper are solely responsible for the content of those articles. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cedarville College, "Cedars, January 21, 2000" (2000). Cedars. 727. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars/727 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Footer Logo DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cedars by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. January 21, 200 oe Stowell..................... 2 Drunk with Marty Ph.Ds......................3 .....................2 Senior Recitalists............. 4 Cedar Faces.................... 5 Well-oiled Honors Band...................7 machines Graves on Worship........... 8 ••••••••• a**** 5 Music Reviews................. 9 Flock flies north Women's Basketball........10 Men's Basketball............ 11 .................... 7 A CEDARVILLE COLLEGE STUDENT PUBLICATION Sidewalk Talk................. 12 CCM star Chris Rice performs on campus again Kristin Rosner but not the sophistication that Staff Writer often comes with the success that Rice has experienced lately. -

Blackberry) Be Saved? Research in Motion (RIM

BM1807 Names _________________________________________ Section ____________ Date____________ ACTIVITY Can Research in Motion (BlackBerry) be Saved? Research in Motion (RIM) was founded in 1984 by Jim Balsillie and Mike Lazaridis as a business focused on providing the backbone for the two-way pager market. In 1999, they released the first BlackBerry device with an embedded full QWERTY keyboard. The “BlackBerry” set the bar for the connected business person. The term “crack berry” was even coined for those business people who could not put down their BlackBerry. The company focused almost exclusively on the integrity of the network on which their phones operated. They provided security measures that made RIM the choice of data managers. When developing a strategy, companies have to bring together all the elements in a manner that provides them with a unique position relative to their competitors. At the time of its release, most competitors provided cell phones that could make calls and little more. BlackBerry changed the nature and use of a portable device and provided a secure platform for IT managers wary of allowing remote devices to access their systems. BlackBerry sales peaked in 2008 about the same time that Apple released the iPhone. Despite that, the company still has tens of millions of users worldwide, a cash hoard over $2.7 billion or P135 billion and a reputation for being a best-in-class device for the business community. The company has made a number of missteps along the way, including a touchscreen BlackBerry that did not catch on, a tablet that lacked e-mail connectivity, and an approach to the market that made it clear that the company believed the backbone was of more value than the device used. -

ABOUT ENVISION CAMBRIDGE Welcome Bienvenidos 欢迎

Issue #1 | Summer 2016 Newspaper A Newspaper Covering the Cambridge Citywide Plan ABOUT ENVISION CAMBRIDGE nvision Cambridge is a Ecommunity-wide process to develop a comprehensive plan for a more livable, sustainable, and equitable Cambridge. With input from those who live, work, study, and play in our city, Envision Cambridge will create a shared vision for the city’s future. The plan will result in recommendations on a broad range of topics such as housing, mobility, economic opportunity, urban form, and climate and the environment. INSIDE FEEDBACK FORUM 2 COMMUNITY SPACE 3 SPOTLIGHT PLAN UPDATES 4-5 PLACES WE LOVE 6 Envision Cambridge Mobile Engagement Station in action at Cambridge City Hall Annex ASK A PLANNER 7 Cambridge community members SIDEWALK TALK 8 see the things we see, meet the DID YOU KNOW? Welcome people we meet, and hear some of I AM CAMBRIDGE 9 the feedback we hear. According to the 2010-2012 Bienvenidos American Community Survey, CITY LENS 10-11 Envision Cambridge Newspaper the predominant occupations of features maps, data, history, fun Cambridge residents are: FUN AND GAMES 12 欢迎 facts, portraits of public spaces, Computer Engineering and and interviews with Cambridge elcome to the Envision Science Occupations - 20% residents, community leaders, Cambridge Newspaper, a GUESS WHAT? W and experts. The features will free publication produced by the Education, Training, and highlight lesser-known aspects of 29.7% Envision Cambridge Team. Library - 16% of Cambridge residents are enrolled the city and its neighborhoods. Management Occupations - 11.9% full time or part time in college or Since Envision Cambridge graduate degree programs. -

Alphabet Board of Directors

WMHSMUN XXXIV Alphabet Board of Directors Background Guide “Unprecedented committees. Unparalleled debate. Unmatched fun.” Letters From the Directors Dear Delegates, Hello delegates! My name is Katie Weinsheimer, and I am looking forward to meeting you all on Zoom this fall at WMHSMUN XXXIV. The world of international Internet governance and the moral/ethical issues that arise from the introduction of ‘smart’ technology have been an interest of mine throughout my college career, so I am very excited to delve into these issues as your committee director for the Alphabet Board of Directors. I am a senior international relations major from Silver Spring, MD. I am in the St. Andrews William & Mary Joint Degree Programme, which means I am coming back to W&M after studying abroad in Scotland for two years. I joined William & Mary’s International Relations Club as a freshman after doing model United Nations in high school like all of you. I have loved my time in the club and have loved being involved in all of the conferences the College hosts. I am currently the registration director for our middle school conference, WMIDMUN XIX. Outside of model UN, I love reading, traveling, and cooking/trying new restaurants. But enough about me, you are here for stock market domination! As the Alphabet Board of Directors, you are responsible for the financial health of Alphabet and its subsidiary companies. Directors are charged with assessing and managing the risk associated with Alphabet’s various investments. This committee will take place in November 2020. With COVID-19 raging and poised to worsen in the winter months, the Board will have to make tough decisions about current and future investments. -

BOARD of GOVERNORS Thursday, June 29, 2017 Jorgenson Hall – JOR 1410 380 Victoria Street 4:00 P.M

BOARD OF GOVERNORS Thursday, June 29, 2017 Jorgenson Hall – JOR 1410 380 Victoria Street 4:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. Time Item Presenter/s Action 4:00 1. IN-CAMERA DISCUSSION (Board Members Only) 4:15 2. IN-CAMERA DISCUSSION (Executive Group Invited) END OF IN-CAMERA DISCUSSION 3. INTRODUCTION 4:40 3.1 Chair’s Remarks Janice Fukakusa Information 3.2 Approval of the June 29, 2017 Agenda Janice Fukakusa Approval 4:45 4. REPORT FROM THE PRESIDENT Mohamed Lachemi Information 4.1 Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences 2017 Pam Sugiman Information Highlights 5:00 5. REPORT FROM THE SECRETARY Julia Shin Doi Information 5.1 Board of Governors Student Leadership Award and Julia Shin Doi Information Medal 5.2 Annual Board Assessments Julia Shin Doi Information 5:05 6. REPORT FROM THE INTERIM PROVOST AND VICE Chris Evans Information PRESIDENT ACADEMIC 6.1 Policy and Procedures Relating to Search Committees Mohamed Lachemi Approval and Appointments in the Academic Administration and Christopher Evans to the Development and Evaluation of the Performance Saeed Zolfaghari of Academic Administrators (“AAA Policy”) 7. DISCUSSION 5:25 7.1 REPORT FROM THE INTERIM VICE PRESIDENT Rivi Frankle Information UNIVERSITY ADVANCEMENT 5:30 7.2 REPORT FROM THE CHAIR OF THE AUDIT COMMITTEE Jack Cockwell Information 7.2.1 Draft Audited Financial Statements -Year Ended April 30, Joanne McKee Approval 2017 7.2.2 Safe Disclosure Policy Janice Winton Approval Scott Clarke 5:40 7.3 REPORT FROM THE CHAIR OF THE EMPLOYEE RELATIONS Mitch Frazer AND PENSION COMMITTEE 7.3.1 Audited Financial Statements of the Ryerson Retirement Christina Sass-Kortsak Approval Pension Plan (RRPP) January 1, 2017 and Audit Findings for the year ending December 31, 2016 7.3.2 Preliminary Valuation of the Ryerson Retirement Mitch Frazer Approval Pension Plan (RRPP) January 1, 2017 Christina Sass-Kortsak 7.3.3 Amendments to the Ryerson Retirement Pension Plan Christina Sass-Kortsak Approval Statement of Investment Policies & Procedures 8. -

Data and the Future of Work

DFW Data and the Future of Work Hettie O’Brien & Mathew Lawrence July 2020 1 —Jul —Jul 20 1. Introduction When a new decade began a few short months ago, few suspected the world would look like this. The coronavirus pandemic is bewildering because it turns on a paradox. Helping others could be deadly; doing nothing can be the best way to do something; apocalyptic events, it turns out, can feel crushingly monotonous. But not everything has changed. One of the most unwelcome continuities from the world we’re leaving behind us is the relentless growth of platform giants and the app-driven future they have sold us under the guise of heightened convenience. As small businesses went bankrupt and workers were laid off, Amazon announced it was hiring an additional 100,000 workers, its founder on course to become the world’s first trillionaire.[1][2] Tesla defied state laws to put its factory back into production while a deadly virus crept across North America.[3] Palantir partnered with NHSX to create a store of aggregated patient data that is likely to outlive the pandemic. [4] These companies appear not just immune to the virus, but strengthened by it. Data and the Future of the Work and the Future Data A state of exception can quickly become the state of play. In a recent report for the Intercept, Naomi Klein described how, rather than seeing our altered reality of physical isolation as an unfortunate but necessary protection against further deaths, tech companies are treating it as a “living laboratory for a permanent – and highly profitable – no-touch future.”[5] This future is one in which our living rooms, already turned into our offices, become our gyms, our GP surgeries, our schools, our therapist couches; where medicine, teaching and exercise instruction are conducted remotely. -

DSAP Supplemental Report on the Sidewalk Labs Digital Innovation Appendix (DIA)

DSAP Supplemental Report on the Sidewalk Labs Digital Innovation Appendix (DIA) Author: Waterfront Toronto’s Digital Strategy Advisory Panel Provided to Waterfront Toronto: February 17, 2020 Published: February 26, 2020 Summary In August 2019, Waterfront Toronto’s Digital Strategy Advisory Panel (DSAP) set out in a Preliminary Commentary its initial impressions, comments and questions on Sidewalk Labs’ Master Innovation Development Plan (MIDP). Since then, significantly more information has been made public about the Quayside project, including a Digital Innovation Appendix (DIA) and the October 31 Threshold Issues Resolution letter. This Report is supplemental to the Preliminary Commentary, identifying areas in which the additional information has addressed (in whole or in part) concerns raised and areas in which questions or concerns remain. Panelists have also taken the opportunity to provide input into other matters relevant to their expertise, including considerations related to digital governance and to Sidewalk Labs as an innovation and funding partner. Comments include, but are not limited to: ● Overall impressions of the DIA: Overall, Panelists were generally in agreement that the DIA was a significant improvement over the MIDP and appreciated the amount of information provided in a more streamlined format. However, concerns remain - notably, that certain critical details are still outstanding. ● Digital Governance: While Panelists support the outcome of the October 31 Threshold Issues resolution, which reaffirmed that digital governance belongs exclusively in the purview of Waterfront Toronto and its government partners, the most significant outstanding issues for Panelists was generally the DSAP Supplemental Report 2 lack of a fully realized digital governance framework and the need for expedited public sector leadership. -

Freedom Liberty

2013 ACCESS AND PRIVACY Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner Ontario, Canada FREEDOM & LIBERTY As Commissioner, I feel that one of the most important parts of my mandate is to engage citizens so that the message of “respect our privacy, respect our freedoms,” can be heard loud and clear. COMMISSIONER’S MESSAGE WHEN I BEGAN MY FIRST TERM AS ONTARIO’S INFORMATION AND PRI- 2009 VACY COMMISSIONER IN 1997, I COULD In 2009, I continued to advance Privacy by NOT HAVE IMAGINED HOW MUCH THE Design on the world stage by launching The 7 WORLD WOULD BE CHANGING! Com- Foundational Principles of Privacy by Design, puters and the Internet were still largely limited which I am proud to say have now been trans- to desktops in homes and offices. Laptops were lated into 35 languages, with more to come. still unwieldy devices, and cellphones were still To ensure that Privacy by Design continued to a long way from becoming “smart.” gain strong global momentum, I also launched Today, information technology is compact, www.privacybydesign.ca as a repository of mobile, and everywhere. You cannot walk down news, information and research. the street without seeing someone using some In an entirely different area, following an exten- sort of mobile device that has more computing sive investigation, I issued a special report en- power than an office floor full of computers, just a generation ago. There is almost no aspect of titled, Excessive Background Checks Conducted our lives left that remains untouched by infor- on Prospective Jurors: A Special Investigation Re- mation and communications technology. -

20777807 Lprob 1.Pdf

Inman Harvey · Ann Cavoukian George Tomko · Don Borrett Hon Kwan · Dimitrios Hatzinakos Editors SmartData Privacy Meets Evolutionary Robotics SmartData Inman Harvey • Ann Cavoukian George Tomko • Don Borrett Hon Kwan • Dimitrios Hatzinakos Editors SmartData Privacy Meets Evolutionary Robotics Editors Inman Harvey Ann Cavoukian School of Informatics Office of the Information University of Sussex and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario Brighton, UK Toronto, ON, Canada George Tomko Don Borrett Identity, Privacy and Security Initiative Department of Medicine University of Toronto University of Toronto Toronto, ON, Canada Toronto, ON, Canada Hon Kwan Dimitrios Hatzinakos Department of Neurophysiology Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Toronto University of Toronto Toronto, ON, Canada Toronto, ON, Canada ISBN 978-1-4614-6408-2 ISBN 978-1-4614-6409-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-6409-9 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013932866 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

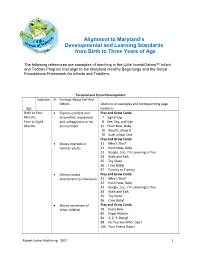

Alignment to Maryland's Developmental and Learning Standards

Alignment to Maryland’s Developmental and Learning Standards from Birth to Three Years of Age The following references are examples of teaching in the Little InvestiGators™ Infant and Toddler Program that align to the Maryland Healthy Beginnings and the Social Foundations Framework for Infants and Toddlers. Personal and Social Development Indicator A. Feelings About Self And Others Citations or examples and corresponding page Age numbers Birth to Four • Express comfort and Play and Grow Cards: Months discomfort, enjoyment 7 Signal Log Four to Eight and unhappiness in her 8 See, Say, and Sign Months environment 22 Hush Now, Baby 76 Read It, Show It 78 Such a Dear One Play and Grow Cards: • Shows interests in 21 Who’s That? familiar adults 22 Hush Now, Baby 23 Gurgle, Coo, I’m Listening to You 24 Walk and Talk 25 Toy Store 26 I See Baby! 97 Tummy to Tummy • Demonstrates Play and Grow Cards: attachment to individuals 21 Who’s That? 22 Hush Now, Baby 23 Gurgle, Coo, I’m Listening to You 24 Walk and Talk 25 Toy Store 26 I See Baby! • Shows awareness of Play and Grow Cards: other children 79 Fuzzy Bear 80 Paper Mobile 81 1, 2, 3, Boing! 98 Do You See Who I See? 100 Your Friend Hops! Robert-Leslie Publishing 2017 1 • Calms herself Play and Grow Cards: 8 See, Say, and Sign 13 Hungry Me! 22 Hush Now, Baby 76 Read It, Show It 78 Such a Dear One Indicator A. Feelings about Self and Others Citations or examples and corresponding page Age B.