Broadcast Journalism: What's Missing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Der Spiegel-Confirmation from the East by Brian Crozier 1993

"Der Spiegel: Confirmation from the East" Counter Culture Contribution by Brian Crozier I WELCOME Sir James Goldsmith's offer of hospitality in the pages of COUNTER CULTURE to bring fresh news on a struggle in which we were both involved. On the attacking side was Herr Rudolf Augstein, publisher of the German news magazine, Der Spiegel; on the defending side was Jimmy. My own involvement was twofold: I provided him with the explosive information that drew fire from Augstein, and I co-ordinated a truly massive international research campaign that caused Augstein, nearly four years later, to call off his libel suit against Jimmy.1 History moves fast these days. The collapse of communism in the ex-Soviet Union and eastern Europe has loosened tongues and opened archives. The struggle I mentioned took place between January 1981 and October 1984. The past two years have brought revelations and confessions that further vindicate the line we took a decade ago. What did Jimmy Goldsmith say, in 1981, that roused Augstein to take legal action? The Media Committee of the House of Commons had invited Sir James to deliver an address on 'Subversion in the Media'. Having read a reference to the 'Spiegel affair' of 1962 in an interview with the late Franz Josef Strauss in his own news magazine of that period, NOW!, he wanted to know more. I was the interviewer. Today's readers, even in Germany, may not automatically react to the sight or sound of the' Spiegel affair', but in its day, this was a major political scandal, which seriously damaged the political career of Franz Josef Strauss, the then West German Defence Minister. -

VOA E2A Fact Sheet

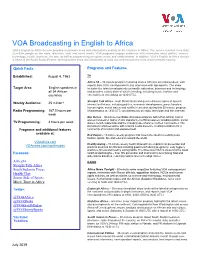

VOA Broadcasting in English to Africa VOA’s English to Africa Service provides multimedia news and information covering all 54 countries in Africa. The service reaches more than 25 million people on the radio, television, web, and social media. VOA programs engage audiences with information about politics, science, technology, health, business, the arts, as well as programming on sports, music and entertainment. In addition, VOA’s English to Africa service is home to the South Sudan Project, which provides news and information to radio and web consumers in the world’s newest country. Quick Facts Programs and Features Established: August 4, 1963 TV Africa 54 – 30-minute program featuring stories Africans are talking about, with reports from VOA correspondents and interviews with top experts. The show Target Area: English speakers in includes the latest developments on health, education, business and technology, all 54 African and provides a daily dose of what’s trending, including music, fashion and countries entertainment (weekdays at 1630 UTC). Straight Talk Africa - Host Shaka Ssali and guests discuss topics of special Weekly Audience: 25 million+ interest to Africans, including politics, economic development, press freedom, human rights, social issues and conflict resolution during this 60-minute program. Radio Programming: 167.5 hours per (Wednesdays at 1830 UTC simultaneously on radio, television and the Internet). week Our Voices – 30-minute roundtable discussion program with a Pan-African cast of women focused on topics of vital importance to African women including politics, social TV Programming: 4 hours per week issues, health, leadership and the changing role of women in their communities. -

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: the Chibok Girls (60

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: The Chibok Girls (60 Minutes) Clarissa Ward (CNN International) CBS News CNN International News Magazine Reporter/Correspondent Abby McEnany (Work in Progress) Danai Gurira (The Walking Dead) SHOWTIME AMC Actress in a Breakthrough Role Actress in a Leading Role - Drama Alex Duda (The Kelly Clarkson Show) Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve) NBCUniversal BBC AMERICA Showrunner – Talk Show Actress in a Supporting Role - Drama Am I Next? Trans and Targeted Francesca Gregorini (Killing Eve) ABC NEWS Nightline BBC AMERICA Hard News Feature Director - Scripted Angela Kang (The Walking Dead) Gender Discrimination in the FBI AMC NBC News Investigative Unit Showrunner- Scripted Interview Feature Better Things Grey's Anatomy FX Networks ABC Studios Comedy Drama- Grand Award BookTube Izzie Pick Ibarra (THE MASKED SINGER) YouTube Originals FOX Broadcasting Company Non-Fiction Entertainment Showrunner - Unscripted Caroline Waterlow (Qualified) Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) ESPN Films FX Networks Producer- Documentary /Unscripted / Non- Actress in a Leading Role - Made for TV Movie Fiction or Limited Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) Mission Unstoppable Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) Produced by Litton Entertainment Actress in a Leading Role - Comedy or Musical Family Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) MSNBC 2019 Democratic Debate (Atlanta) Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) MSNBC Director - Comedy Special or Variety - Breakthrough Naomi Watts (The Loudest Voice) Sharyn Alfonsi (60 Minutes) SHOWTIME -

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković porocilo.indb 327 20.5.2014 9:04:47 INTRODUCTION Serbia’s transition to democratic governance started in 2000. Reconstruction of the media system – aimed at developing free, independent and pluralistic media – was an important part of reform processes. After 13 years of democratisation eff orts, no one can argue that a new media system has not been put in place. Th e system is pluralistic; the media are predominantly in private ownership; the legal framework includes European democratic standards; broadcasting is regulated by bodies separated from executive state power; public service broadcasters have evolved from the former state-run radio and tel- evision company which acted as a pillar of the fallen autocratic regime. However, there is no public consensus that the changes have produced more positive than negative results. Th e media sector is liberalized but this has not brought a better-in- formed public. Media freedom has been expanded but it has endangered the concept of socially responsible journalism. Among about 1200 media outlets many have neither po- litical nor economic independence. Th e only industrial segments on the rise are the enter- tainment press and cable channels featuring reality shows and entertainment. Th e level of professionalism and reputation of journalists have been drastically reduced. Th e current media system suff ers from many weaknesses. Media legislation is incom- plete, inconsistent and outdated. Privatisation of state-owned media, stipulated as mandato- ry 10 years ago, is uncompleted. Th e media market is very poorly regulated resulting in dras- tically unequal conditions for state-owned and private media. -

Education Issue

march 2010 Education Issue Michael Bublé on Great Performances American Masters: I.M. Pei LEARNING IS LIFE’S TREASURE By partnering for the common good we can achieve uncommon results. Chase proudly supports the Celebration of Teaching & Learning with Thirteen/WNET and WLIW21. We salute all educators who dedicate themselves to our children. thirteen.org 1 ducatIon Is at the Our Education Department works heart of everything we year-round on a variety of outreach do at THIRTEEN. As a programs and special initiatives for pioneering provider of students, educators, and parents in New quality television and York State and beyond. Ron Thorpe, Vice web content, unique local President and Director of Education at Eproductions, and innovative educational WNET.ORG, offers an inside look at this and cultural projects, our mission is to vibrant department on page 2. enrich the lives of our community—from Our commitment to education extends pre-schoolers and adult learners to those into the community with Curious George who have a passion for lifelong learning. Saves the Day: The Art of Margret and This special edition of THIRTEEN— H.A. Rey, a fascinating exhibit opening our second annual Education Issue March 14 at The Jewish Museum. See —showcases some of our most exciting page 14 to learn about the exhibit, as well huschka educational endeavors. as special offers available exclusively to jane : : On March 5 and 6, the fifth annual THIRTEEN members. Celebration of Teaching & Learning comes Finally, we’re proud to launch our to New York City. The nation’s premier newly expanded children’s website, Kids llustrations I professional development conference for THIRTEEN (kids.thirteen.org). -

Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time

The Business of Getting “The Get”: Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung The Joan Shorenstein Center I PRESS POLITICS Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 IIPUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government The Business of Getting “The Get” Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 INTRODUCTION In “The Business of Getting ‘The Get’,” TV to recover a sense of lost balance and integrity news veteran Connie Chung has given us a dra- that appears to trouble as many news profes- matic—and powerfully informative—insider’s sionals as it does, and, to judge by polls, the account of a driving, indeed sometimes defining, American news audience. force in modern television news: the celebrity One may agree or disagree with all or part interview. of her conclusion; what is not disputable is that The celebrity may be well established or Chung has provided us in this paper with a an overnight sensation; the distinction barely nuanced and provocatively insightful view into matters in the relentless hunger of a Nielsen- the world of journalism at the end of the 20th driven industry that many charge has too often century, and one of the main pressures which in recent years crossed over the line between drive it as a commercial medium, whether print “news” and “entertainment.” or broadcast. One may lament the world it Chung focuses her study on how, in early reveals; one may appreciate the frankness with 1997, retired Army Sergeant Major Brenda which it is portrayed; one may embrace or reject Hoster came to accuse the Army’s top enlisted the conclusions and recommendations Chung man, Sergeant Major Gene McKinney—and the has given us. -

Ammast 03 Lettrhd Press 3 Holed

offset usage 4-color process Output is set for 2500dpi 450 West 33rd Street New York NY 10001-2605 thirteen.org press information AMERICAN MASTERS BRINGS BIG SCREEN MAGIC TO THE SMALL SCREEN WITH YOU MUST REMEMBER THIS: THE WARNER BROS. STORY Series from Thirteen/WNET Premieres This Fall on PBS AMERICAN MASTERS is produced for PBS by Thirteen/WNET The colorful 85-year legacy of Warner Bros. is documented in an unprecedented film project, New York AMERICAN MASTERS You Must Remember This: The Warner Bros. Story, narrated by Clint Eastwood. The five-hour film, a Lorac production in partnership with AMERICAN MASTERS and Warner Bros. Entertainment, premieres nationally, September 23, 24 and 25 at 9 p.m. (ET) on PBS (check local listings). The film is directed, written and produced by award-winning filmmaker and film critic Richard Schickel. Eastwood is executive producer. “I think it’s wonderful and fitting that Richard Schickel, who produced his first big series The Men Who Made the Movies for public television in 1973, is returning to public television with this project – the epic and historic and thoroughly juicy Warner Bros. story,” says Susan Lacy, creator and Executive Producer of AMERICAN MASTERS, a five-time winner of the Emmy Award for Outstanding Primetime Non-Fiction Series. Through movie clips, rare archival interviews, newly photographed material, and insightful on-camera discussions with talent such as Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Clooney, Warren Beatty, Sidney Lumet, Jack Nicholson, and many others, You Must Remember This gives us the history of 20th century America on the big screen. -

FOCUS™ Edit Search

Home Sources How Do I? Site Map What's New Help Search Terms: "corporation for public broadcasting", "new york times" FOCUS™ Edit Search Document 4 of 34. Copyright 2005 Los Angeles Times All Rights Reserved Los Angeles Times May 29, 2005 Sunday Home Edition SECTION: SUNDAY CALENDAR; Calendar Desk; Part E; Pg. 17 LENGTH: 1305 words HEADLINE: MEDIA MATTERS / DAVID SHAW; There's a 'nuclear option' for PBS' woes as well BYLINE: DAVID SHAW BODY: The growing controversy over the Bush administration's attempts to replace what it sees as a "liberal bias" in PBS programming with what would appear to be "conservative bias" has forced me to think the unthinkable -- or at least the heretical, certainly in my cultural/ideological circle: Do we really want or need PBS anymore? I am not defending the Bush administration's assault on PBS, which is as appalling as it is predicable, nor do I mean to denigrate the fine, often brilliant work PBS has done through the years -- "Masterpiece Theater," "Firing Line," "Bill Moyers' Journal," Ken Burns' epic documentaries on the Civil War, baseball and jazz, among many others. But when the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the parent of PBS, was created by the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, we lived in a television world largely limited to three commercial networks, a world quite accurately characterized as a "vast wasteland" by Newton Minow, then chairman of the FCC. We now live in a cable world, a "500-channel universe," and while I would not argue that many of these cable offerings match PBS at its best, they (and Fox) do provide many alternatives to the three original networks we had in 1967. -

Nbc News, Msnbc and Cnbc Honored with 23 News and Documentary Emmy Award Nominations

NBC NEWS, MSNBC AND CNBC HONORED WITH 23 NEWS AND DOCUMENTARY EMMY AWARD NOMINATIONS “Rock Center with Brian Williams” Honored with Five Nominations in First Eligible Season "NBC Nightly News" Nominated for Eight Awards, Including Two For "Blown Away: Southern Tornadoes" and "Mexico: The War Next Door" "Dateline" Honored with Five Nominations Including Two for "Rescue in the Mountains" "Education Nation" Receives Two Nominations Including “Outstanding News Discussion & Analysis” MSNBC Honored with Two Nominations including “Outstanding News Discussion & Analysis” CNBC Nominated for “Outstanding Business & Economic Reporting” NEW YORK -- July 12, 2012 -- NBC News, MSNBC and CNBC have received a total of 23 News and Documentary Emmy Award nominations, the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences announced today. The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Monday, October 1 at a ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, located in the Time Warner Center in New York City. The following is a breakdown of the 23 nominations by network and show. "NBC Nightly News" was nominated in the following categories: OUTSTANDING COVERAGE OF A BREAKING NEWS STORY IN A REGULARLY SCHEDULED NEWSCAST: "NBC Nightly News" – Blown Away: Southern Tornadoes "NBC Nightly News " – Disaster in Japan "NBC Nightly News " – The Fall of Mubarak OUTSTANDING CONTINUING COVERAGE OF A NEWS STORY IN A REGULARLY SCHEDULED NEWSCAST: "NBC Nightly News" – Battle for Libya "NBC Nightly News" – Mexico: The War Next Door "NBC Nightly News" -

Barbara Cochran

Cochran Rethinking Public Media: More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive More Inclusive, Local, More More Rethinking Media: Public Rethinking PUBLIC MEDIA More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive A WHITE PAPER BY BARBARA COCHRAN Communications and Society Program 10-021 Communications and Society Program A project of the Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program A project of the Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Rethinking Public Media: More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive A White Paper on the Public Media Recommendations of the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities in a Democracy written by Barbara Cochran Communications and Society Program December 2010 The Aspen Institute and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation invite you to join the public dialogue around the Knight Commission’s recommendations at www.knightcomm.org or by using Twitter hashtag #knightcomm. Copyright 2010 by The Aspen Institute The Aspen Institute One Dupont Circle, NW Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20036 Published in the United States of America in 2010 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0-89843-536-6 10/021 Individuals are encouraged to cite this paper and its contents. In doing so, please include the following attribution: The Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program,Rethinking Public Media: More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive, Washington, D.C.: The Aspen Institute, December 2010. For more information, contact: The Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program One Dupont Circle, NW Suite 700 Washington, D.C. -

Magazine Template

Saint Joseph’s University, Summer 2011 Smiles, Support and … Snowflakes? Historic Celebration Marks Alumna Finds Success, RAs, Hawk Hosts and Red Shirts Record-Breaking Capital Campaign Persistence to Earn Degree Pays Off F ROMTHE I NTERIM P RESIDENT As alumni and friends of Saint Joseph’s University, you know that Hawk Hill is a unique and wonderful place. From my own experience — as a student, former chair of the Board of Trustees, and most recently, as senior vice president — this is something I share with you. While we continue our search for Saint Joseph’s next president, with the guidance of both our Jesuit community and the Board of Trustees, I am honored to serve the University as interim president. Thanks to the vision and leadership of Nicholas S. Rashford, S.J., our 25th president, and Timothy R. Lannon, S.J., our 26th, Saint Joseph’s has been on a trajectory of growth and excellence that has taken us to places we never dreamed were possible. Rightfully so, we are proud of all of our achievements, but we are also mindful that we are charged with moving Saint Joseph’s into the future surely and confidently. The University’s mission — which is steeped in our Catholic, Jesuit heritage — is too important to be approached in any other way. In an address to the leaders of American Jesuit colleges and universities when he was Superior General of the Society of Jesus, Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S.J., affirmed: You are who your students become. Saint Joseph’s identity, then, is ultimately tied to the people our students become in the world, and the broad outline of their character reveals them to be leaders with high moral standards, whose ethics are grounded in and informed by a faith that serves justice. -

The Glocal News Magazine on France

FRANCE IN MALTA Bonj(o)u(r) The glocal news magazine on France Monthly! Vol. 03.02 - April 2011 France and partners Art France and Malta Tech & Science In-depth Calendar act to protect civilians Cultural and personal A look at scientific and Bread. The word says A quick look at the in Libya Who knows about the links that have built technical acheivements it all Maltese-French France, USA and Great Caillebotte brothers? strong bonds across the in France from robotics calendar Britain work hand ages. to medecine Page 2 Page 3 Page 6 Page 7 Page 4 Page 9 défaites et victoires-, d’un ou CNRS et la tenue d’un important plusieurs peuples. Parmi les mots colloque (Mistrals) de scientifiques essentiels de la francophonie : méditerranéens s’inscrivent dans fraternité, identité, liberté. Trois mots cette tradition venue de loin. qui appartiennent à tout le monde. Pendant plusieurs jours, accueillis Chacun d’entre nous peut les par Juanito Camillieri et Charles comprendre et les faire rayonner, de Sammut, deux cents chercheurs, - là où nous sommes et où nous israéliens, palestiniens, tunisiens, travaillons, dans cet archipel, au marocains, libanais, turcs, maltais, cœur d’une mer qui nous a beaucoup français, etc. -, ont travaillé ensemble appris et beaucoup donné. à l’ancienne université sur un L’univers méditerranéen a été en effet programme du futur. Pour notre l’un des berceaux de la science pays, l’Europe n’a pas d’avenir sans Pour la première fois, la francophonie universelle. C’est sous l’influence la Méditerranée. La rive sud est a été célébrée à Malte par tous les d’Aristote que le Musée est devenu aujourd’hui traversée par un souffle ambassadeurs francophones.