The Frequency of Anglicisms in the German News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Der Spiegel-Confirmation from the East by Brian Crozier 1993

"Der Spiegel: Confirmation from the East" Counter Culture Contribution by Brian Crozier I WELCOME Sir James Goldsmith's offer of hospitality in the pages of COUNTER CULTURE to bring fresh news on a struggle in which we were both involved. On the attacking side was Herr Rudolf Augstein, publisher of the German news magazine, Der Spiegel; on the defending side was Jimmy. My own involvement was twofold: I provided him with the explosive information that drew fire from Augstein, and I co-ordinated a truly massive international research campaign that caused Augstein, nearly four years later, to call off his libel suit against Jimmy.1 History moves fast these days. The collapse of communism in the ex-Soviet Union and eastern Europe has loosened tongues and opened archives. The struggle I mentioned took place between January 1981 and October 1984. The past two years have brought revelations and confessions that further vindicate the line we took a decade ago. What did Jimmy Goldsmith say, in 1981, that roused Augstein to take legal action? The Media Committee of the House of Commons had invited Sir James to deliver an address on 'Subversion in the Media'. Having read a reference to the 'Spiegel affair' of 1962 in an interview with the late Franz Josef Strauss in his own news magazine of that period, NOW!, he wanted to know more. I was the interviewer. Today's readers, even in Germany, may not automatically react to the sight or sound of the' Spiegel affair', but in its day, this was a major political scandal, which seriously damaged the political career of Franz Josef Strauss, the then West German Defence Minister. -

VOA E2A Fact Sheet

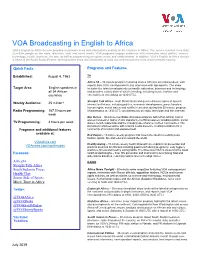

VOA Broadcasting in English to Africa VOA’s English to Africa Service provides multimedia news and information covering all 54 countries in Africa. The service reaches more than 25 million people on the radio, television, web, and social media. VOA programs engage audiences with information about politics, science, technology, health, business, the arts, as well as programming on sports, music and entertainment. In addition, VOA’s English to Africa service is home to the South Sudan Project, which provides news and information to radio and web consumers in the world’s newest country. Quick Facts Programs and Features Established: August 4, 1963 TV Africa 54 – 30-minute program featuring stories Africans are talking about, with reports from VOA correspondents and interviews with top experts. The show Target Area: English speakers in includes the latest developments on health, education, business and technology, all 54 African and provides a daily dose of what’s trending, including music, fashion and countries entertainment (weekdays at 1630 UTC). Straight Talk Africa - Host Shaka Ssali and guests discuss topics of special Weekly Audience: 25 million+ interest to Africans, including politics, economic development, press freedom, human rights, social issues and conflict resolution during this 60-minute program. Radio Programming: 167.5 hours per (Wednesdays at 1830 UTC simultaneously on radio, television and the Internet). week Our Voices – 30-minute roundtable discussion program with a Pan-African cast of women focused on topics of vital importance to African women including politics, social TV Programming: 4 hours per week issues, health, leadership and the changing role of women in their communities. -

The Polish Phenomenon What’S Next for Europe’S New Powerhouse?

Report on the Kosciuszko Foundation Economic Conference 2013 The Polish Phenomenon What’s Next for Europe’s New Powerhouse? PRODUCED BY CONTENTS FOREWORD: Shedding Light on the Polish Phenomenon ........................... 1 PANEL ONE: Riding Out the Storm—How the Finance and Banking Sector in Poland Navigated the Recession and the Path Ahead ........................................................................................ 2 KEYNOTE SPEAKER: Marek Belka, President of the National Bank of Poland .................................................... 12 KEYNOTE PRESENTATION: The Polish Economy and the Global Financial Crisis—Strengths and Challenges ..................................... 13 PANEL TWO: The Land of Opportunity—an Investor Perspective .............. 20 THE KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION: The American Center of Polish Culture ........................................................ 30 FOREWORD Shedding Light on the Polish Phenomenon THERE’S AN OLD JOKE ABOUT HOW MANY POLES IT TOOK TO SCREW IN A LIGHT BULB. BUT AFTER A POLISH ELECTRICIAN NAMED LECH WALESA PULLED THE PLUG ON COMMUNISM AND HELPED BRING DOWN THE SOVIET UNION, THAT JOKE LOST ITS LUSTER. THESE DAYS THE LIGHT BULBS ARE MADE IN POLAND, AND OVER THE PAST TWO DECADES, THE COUNTRY’S ECONOMY HAS GROWN AT A RECORD PACE COMPARED TO ITS NEIGHBORS. September 2013 marked the 20th anniversary of Russia’s withdrawal of the Soviet army from Poland. Since then, Poland has gone from Communist basket case to what German magazine Der Spiegel dubbed last year as: “The Miracle Next Door: Poland Emerges as a Central European Powerhouse.” Poland is the only European Union economy to avoid recession since the global nancial crisis hit in 2008. Polish workers used to travel abroad to where the factories were. These days, factories move ALEX STOROZYNSKI to where the Polish workers are. -

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: the Chibok Girls (60

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: The Chibok Girls (60 Minutes) Clarissa Ward (CNN International) CBS News CNN International News Magazine Reporter/Correspondent Abby McEnany (Work in Progress) Danai Gurira (The Walking Dead) SHOWTIME AMC Actress in a Breakthrough Role Actress in a Leading Role - Drama Alex Duda (The Kelly Clarkson Show) Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve) NBCUniversal BBC AMERICA Showrunner – Talk Show Actress in a Supporting Role - Drama Am I Next? Trans and Targeted Francesca Gregorini (Killing Eve) ABC NEWS Nightline BBC AMERICA Hard News Feature Director - Scripted Angela Kang (The Walking Dead) Gender Discrimination in the FBI AMC NBC News Investigative Unit Showrunner- Scripted Interview Feature Better Things Grey's Anatomy FX Networks ABC Studios Comedy Drama- Grand Award BookTube Izzie Pick Ibarra (THE MASKED SINGER) YouTube Originals FOX Broadcasting Company Non-Fiction Entertainment Showrunner - Unscripted Caroline Waterlow (Qualified) Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) ESPN Films FX Networks Producer- Documentary /Unscripted / Non- Actress in a Leading Role - Made for TV Movie Fiction or Limited Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) Mission Unstoppable Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) Produced by Litton Entertainment Actress in a Leading Role - Comedy or Musical Family Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) MSNBC 2019 Democratic Debate (Atlanta) Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) MSNBC Director - Comedy Special or Variety - Breakthrough Naomi Watts (The Loudest Voice) Sharyn Alfonsi (60 Minutes) SHOWTIME -

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković porocilo.indb 327 20.5.2014 9:04:47 INTRODUCTION Serbia’s transition to democratic governance started in 2000. Reconstruction of the media system – aimed at developing free, independent and pluralistic media – was an important part of reform processes. After 13 years of democratisation eff orts, no one can argue that a new media system has not been put in place. Th e system is pluralistic; the media are predominantly in private ownership; the legal framework includes European democratic standards; broadcasting is regulated by bodies separated from executive state power; public service broadcasters have evolved from the former state-run radio and tel- evision company which acted as a pillar of the fallen autocratic regime. However, there is no public consensus that the changes have produced more positive than negative results. Th e media sector is liberalized but this has not brought a better-in- formed public. Media freedom has been expanded but it has endangered the concept of socially responsible journalism. Among about 1200 media outlets many have neither po- litical nor economic independence. Th e only industrial segments on the rise are the enter- tainment press and cable channels featuring reality shows and entertainment. Th e level of professionalism and reputation of journalists have been drastically reduced. Th e current media system suff ers from many weaknesses. Media legislation is incom- plete, inconsistent and outdated. Privatisation of state-owned media, stipulated as mandato- ry 10 years ago, is uncompleted. Th e media market is very poorly regulated resulting in dras- tically unequal conditions for state-owned and private media. -

Pr Never Judge a Book by Its Cover

NEVER JUDGE A BOOK BY ITS COVER Effearte is pleased to present the next group show “Never Judge A Book By Its Cover”. 13 artists will explore the illustration and publishing industry throughout cover books. Lately everybody talks about it. Adelphi organized a cover contest on its Facebook page, Garzanti asked his readers to choose the cover of the next upcoming book publishing, La Stampa and Il Sole 24 Ore dedicated a column to this subject. A book cover is essential. It is its garment and tells us everything about it. Very often we choose a book for its look and sometimes we don’t buy it because it doesn’t attract us. In the last decade the world of book covers, which is in constant evolution, pushed itself on themes that would have been totally unthinkable before. This is thanks to wishful thinkers art directors, brave editors and, at least but not last, the tremendous contribution of certain artists who offered their art to the editorial world. Among others, very relevant was proved to be the restyling process carried out by some of the most important publishing houses of famous authors such as Einaudi with Murakami or Feltrinelli with Bukowski and Miller. This process ended up being the result of a synthesis between aesthetic and significance. All the works are illustrations of book covers. Never Judge a Book By Its Cover is a panning shot of the most significant Italian (and not only) illustrators who provide their talent and their art to the publishing world, leaving an important and distinguishable sign. -

Application/Pdf Checkout-Charlie Company

Welcome to Berlin, 23th of February 2021 News to categories click to INTERACTIVE DOCUMENT see website Use the interactive buttons to navigate through the presentation. You can find them in the index, too. back to index Content ABOUT US NEWS PORTALS 04 Checkout Charlie 10 A lot has happened 19 Incredible diversity WELCOME PACKAGES CONTENT OFFERS MULTIMEDIA OFFER 33 Your start with us 39 Content & campaigns 51 Visual and auditory EXPERTS CONTACT PERSON APPENDIX 55 For your appearance 57 Individual support 61 Newsletter, Incentive & more 04 About us From a bargain blog to a respected partner for content & discount campaigns, it has been an exciting path for us. And Checkout Charlie continues to develop further. We are pleased that you continue to accompany us as a partner on this exciting journey. ▪ Timeline ▪ Our markets ▪ The Checkout Charlie universe ▪ Facts About us News Portals Welcome Content Multimedia Experts Contact Once upon a time — from a blog to an all-rounder For more than 12 years, we have been making the world Sparwelt.de started as a bargain shopping blog of online shopping a little bit better every day. And in 2008 doing so we focus just as much on our users as on our SPARWELT goes content partners. – with editorial content enjoyed by more than 2012 That‘s why our motto, “Shop better. Feel better.”, is our 1 million users/month greatest credo. SPARWELT joins the Media Group RTL We have been constantly developing our portal and 2014 Germany network, as well as our offers and services, from the Our first TV spot very start — driven by our own motivation to fulfil the campaign generates needs of users and retailers. -

Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time

The Business of Getting “The Get”: Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung The Joan Shorenstein Center I PRESS POLITICS Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 IIPUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government The Business of Getting “The Get” Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 INTRODUCTION In “The Business of Getting ‘The Get’,” TV to recover a sense of lost balance and integrity news veteran Connie Chung has given us a dra- that appears to trouble as many news profes- matic—and powerfully informative—insider’s sionals as it does, and, to judge by polls, the account of a driving, indeed sometimes defining, American news audience. force in modern television news: the celebrity One may agree or disagree with all or part interview. of her conclusion; what is not disputable is that The celebrity may be well established or Chung has provided us in this paper with a an overnight sensation; the distinction barely nuanced and provocatively insightful view into matters in the relentless hunger of a Nielsen- the world of journalism at the end of the 20th driven industry that many charge has too often century, and one of the main pressures which in recent years crossed over the line between drive it as a commercial medium, whether print “news” and “entertainment.” or broadcast. One may lament the world it Chung focuses her study on how, in early reveals; one may appreciate the frankness with 1997, retired Army Sergeant Major Brenda which it is portrayed; one may embrace or reject Hoster came to accuse the Army’s top enlisted the conclusions and recommendations Chung man, Sergeant Major Gene McKinney—and the has given us. -

Press, Radio and Television in the Federal Republic of Germany

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 353 617 CS 508 041 AUTHOR Hellack, Georg TITLE Press, Radio and Television in the Federal Republic of Germany. Sonderdienst Special Topic SO 11-1992. INSTITUTION Inter Nationes, Bonn (West Germany). PUB DATE 92 NOTE 52p.; Translated by Brangwyn Jones. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Developing Nations; Foreign Countries; Freedom of Speech; *Mass Media; *Mass Media Effects; *Mass Media Role; Media Research; Professional Training; Technological Advancement IDENTIFIERS *Germany; Historical Background; Journalists; Market Analysis; Media Government Relationship; Media Ownership; Third World; *West Germany ABSTRACT Citing statistics that show that its citizens are well catered for by the mass media, this paper answers questions concerning the media landscape in the Federal Republic of Germany. The paper discusses: (1) Structure and framework conditions of the German media (a historical review of the mass media since 1945); (2) Press (including its particular reliance on local news and the creation of the world status media group, Bertelsmann AG);(3) News agencies and public relations work (which insure a "never-ending stream" of information);(4) Radio and Television (with emphasis on the Federal Republic's surprisingly large number of radio stations--public, commercial, and "guest");(5) New communication paths and media (especially communication and broadcasting satellites and cable in wideband-channel networks);(6) The profession of journalist (which still relies on on-the-job training rather than university degrees); and (7) Help for the media in the Third World (professional training in Germany of journalists and technical experts from underdeveloped countries appears to be the most appropriate way to promote Third World media). -

Capital in the 21St Century and Bias in German Print Media

Focus CAPITAL IN THE 21ST CENTURY served evolutions. Using a moderate number of equa- tions (most notably α = r *β, relating the capital share AND BIAS IN GERMAN PRINT of income to the interest rate and the capital income s MEDIA ratio, and β = /g, relating the capital income ratio to the savings rate and economic growth), Piketty ex- plains the macroeconomic dynamics of income and CHRISTOPH SCHINKE* wealth in a way that even non-economists can under- stand. He stresses the role of educational, fiscal, mon- etary and other institutions; and he explains how the Capital in the 21st Century has received a huge amount inequality r > g between the return to capital r and the of media coverage and sparked a heated debate on economic growth rate g matters for wealth inequality wealth and income distribution. When the French edi- dynamics. This inequality is observable in the data for tion was first released in August 2013, it was discussed, the last two millennia (Figure 10.9 in his book), except if at all, exclusively in the book review sections of for a period after 1913 when the return to capital after German newspapers. However, the English version, tax and capital losses was lower than the economic published in March 2014, attracted a great deal of at- growth rate (see also Figure 10.11 in his book). tention. The book received another wave of media cov- Thirdly, Piketty makes policy proposals, which chiefly erage when the German translation was released in consist of introducing a global tax on capital to re- October 2014. -

Nbc News, Msnbc and Cnbc Honored with 23 News and Documentary Emmy Award Nominations

NBC NEWS, MSNBC AND CNBC HONORED WITH 23 NEWS AND DOCUMENTARY EMMY AWARD NOMINATIONS “Rock Center with Brian Williams” Honored with Five Nominations in First Eligible Season "NBC Nightly News" Nominated for Eight Awards, Including Two For "Blown Away: Southern Tornadoes" and "Mexico: The War Next Door" "Dateline" Honored with Five Nominations Including Two for "Rescue in the Mountains" "Education Nation" Receives Two Nominations Including “Outstanding News Discussion & Analysis” MSNBC Honored with Two Nominations including “Outstanding News Discussion & Analysis” CNBC Nominated for “Outstanding Business & Economic Reporting” NEW YORK -- July 12, 2012 -- NBC News, MSNBC and CNBC have received a total of 23 News and Documentary Emmy Award nominations, the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences announced today. The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Monday, October 1 at a ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, located in the Time Warner Center in New York City. The following is a breakdown of the 23 nominations by network and show. "NBC Nightly News" was nominated in the following categories: OUTSTANDING COVERAGE OF A BREAKING NEWS STORY IN A REGULARLY SCHEDULED NEWSCAST: "NBC Nightly News" – Blown Away: Southern Tornadoes "NBC Nightly News " – Disaster in Japan "NBC Nightly News " – The Fall of Mubarak OUTSTANDING CONTINUING COVERAGE OF A NEWS STORY IN A REGULARLY SCHEDULED NEWSCAST: "NBC Nightly News" – Battle for Libya "NBC Nightly News" – Mexico: The War Next Door "NBC Nightly News" -

Magazine Template

Saint Joseph’s University, Summer 2011 Smiles, Support and … Snowflakes? Historic Celebration Marks Alumna Finds Success, RAs, Hawk Hosts and Red Shirts Record-Breaking Capital Campaign Persistence to Earn Degree Pays Off F ROMTHE I NTERIM P RESIDENT As alumni and friends of Saint Joseph’s University, you know that Hawk Hill is a unique and wonderful place. From my own experience — as a student, former chair of the Board of Trustees, and most recently, as senior vice president — this is something I share with you. While we continue our search for Saint Joseph’s next president, with the guidance of both our Jesuit community and the Board of Trustees, I am honored to serve the University as interim president. Thanks to the vision and leadership of Nicholas S. Rashford, S.J., our 25th president, and Timothy R. Lannon, S.J., our 26th, Saint Joseph’s has been on a trajectory of growth and excellence that has taken us to places we never dreamed were possible. Rightfully so, we are proud of all of our achievements, but we are also mindful that we are charged with moving Saint Joseph’s into the future surely and confidently. The University’s mission — which is steeped in our Catholic, Jesuit heritage — is too important to be approached in any other way. In an address to the leaders of American Jesuit colleges and universities when he was Superior General of the Society of Jesus, Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S.J., affirmed: You are who your students become. Saint Joseph’s identity, then, is ultimately tied to the people our students become in the world, and the broad outline of their character reveals them to be leaders with high moral standards, whose ethics are grounded in and informed by a faith that serves justice.